Young's Modulus in Bioelectronics: Engineering Soft Materials for Seamless Tissue Integration and Advanced Therapies

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Young's modulus as a critical design parameter in bioelectronic materials.

Young's Modulus in Bioelectronics: Engineering Soft Materials for Seamless Tissue Integration and Advanced Therapies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Young's modulus as a critical design parameter in bioelectronic materials. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental challenge of mechanical mismatch with biological tissues, surveys innovative material strategies like hydrogels and soft composites, and details optimization techniques for enhanced device stability and signal fidelity. The content further covers rigorous validation methodologies and comparative analyses of material performance, offering a holistic guide for developing next-generation bioelectronic implants and therapies that seamlessly integrate with the body.

The Mechanical Mismatch Problem: Why Young's Modulus is Critical for Biointegration

Defining Young's Modulus and Its Significance in Bioelectronic Interfaces

Young's modulus, a fundamental mechanical property quantifying material stiffness, has emerged as a critical parameter in the development of advanced bioelectronic interfaces. This technical guide examines the definition and calculation of Young's modulus, explores its pivotal role in ensuring mechanical compatibility between electronic devices and biological tissues, and details experimental methodologies for its characterization. The convergence of materials science and biomedical engineering has positioned Young's modulus as a central design criterion for next-generation bioelectronic systems that maintain long-term stability and functionality within biological environments. By establishing clear relationships between material stiffness and biointerface performance, this review provides researchers with foundational knowledge and practical frameworks for developing mechanically-compliant bioelectronic devices.

Young's modulus (E), also referred to as the elastic modulus, is a fundamental mechanical property that quantifies the stiffness of a solid material. It is defined as the ratio of stress (force per unit area) to strain (proportional deformation) in a material within the linear elasticity regime of a uniaxial deformation [1] [2]. This property serves as a direct measure of a material's resistance to elastic deformation under applied load, with higher values indicating greater stiffness.

The mathematical expression of Young's modulus is derived from Hooke's Law for elastic materials:

E = σ/ε

Where:

- E is Young's modulus (Pa or GPa)

- σ is the tensile stress (force per unit area, F/A)

- ε is the axial strain (change in length per original length, ΔL/L₀) [1]

This relationship can be expanded to the practical calculation form:

E = (F × L₀) / (A × ΔL)

Where F is the applied force, A is the cross-sectional area, L₀ is the original length, and ΔL is the change in length [1]. In essence, materials with a high Young's modulus (such as metals and ceramics) deform minimally under applied stress, while those with a low Young's modulus (such as rubbers and gels) exhibit significant deformation under the same conditions [2].

The conceptual understanding of Young's modulus can be traced to 18th-century experiments by Giordano Riccati, though it bears the name of the 19th-century British scientist Thomas Young [1]. Its significance extends across engineering disciplines, particularly in bioelectronics, where it determines how seamlessly synthetic materials can integrate with biological systems.

The Critical Role of Young's Modulus in Bioelectronic Interfaces

The Mechanical Mismatch Challenge

Bioelectronic interfaces bridge the divide between electronic devices and biological tissues, enabling advanced monitoring, regulation, and interaction with living organisms [3]. A fundamental challenge in this field stems from the significant discrepancy between the mechanical properties of conventional electronic materials and those of biological tissues:

- Conventional electronics typically utilize rigid materials like silicon and metals with Young's moduli in the gigapascal (GPa) range (e.g., silicon ~130-180 GPa, gold ~79 GPa) [4] [5]

- Biological tissues are soft, dynamic structures with moduli in the kilopascal (kPa) range (e.g., brain tissue ~1-4 kPa, skin ~0.5-2 MPa) [6] [7]

This mechanical mismatch of several orders of magnitude creates substantial challenges at the biointerface. Traditional rigid devices interact with tissues as de facto foreign bodies, leading to:

- Inflammation and fibrotic encapsulation through the foreign body response [8]

- Tissue damage and chronic inflammation during natural tissue movement [5]

- Unstable electrical interfaces and signal degradation over time [5]

- Device failure due to shear stresses and micromotion at the tissue-device interface [4]

Consequences of Mechanical Mismatch

The biological response to mechanically mismatched implants significantly compromises device functionality. Following implantation, the body recognizes stiff materials as foreign, triggering a cascade of events including protein adsorption, inflammatory cell recruitment, and fibroblast activation. This ultimately results in the formation of a fibrous capsule that isolates the device from the target tissue [8].

For neural interfaces, this fibrotic response is particularly detrimental. The encapsulation layer:

- Increases electrode impedance, reducing signal-to-noise ratio in recording applications [5]

- Elevates stimulation thresholds, requiring higher currents for effective neuromodulation [8]

- Physically displaces electrodes from their target neurons, diminishing spatial resolution [5]

Studies have demonstrated that rigid microelectrodes experience significant signal degradation over weeks to months as this foreign body response progresses [5]. Furthermore, the mechanical strain concentration at the interface between moving tissue and stiff implants can lead to both tissue damage and device failure through fatigue or delamination [6].

Quantitative Analysis of Young's Modulus in Biological and Synthetic Materials

Young's Modulus of Biological Tissues

Table 1: Young's Modulus Ranges of Biological Tissues and Conventional Electronics

| Material Category | Specific Material/Tissue | Young's Modulus Range | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neural Tissue | Brain Tissue | 1 - 4 kPa | [7] |

| Peripheral Tissues | Skin | 0.5 - 2 MPa | [6] |

| Cardiac Tissue | Heart | 100 - 500 kPa | [6] |

| Conventional Electronics | Silicon | 130 - 180 GPa | [5] |

| Conventional Electronics | Metals (Gold, Platinum) | 70 - 170 GPa | [4] |

| Conventional Electronics | Traditional Elastomers | 1 - 10 MPa | [6] |

Young's Modulus of Advanced Bioelectronic Materials

Table 2: Young's Modulus of Advanced Bioelectronic Materials

| Material Category | Specific Material | Young's Modulus | Tissue Compatibility | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conductive Polymers | PEDOT:PSS (annealed) | 1.1 MPa - 1.5 GPa | Moderate | [7] |

| Conductive Polymers | PEDOT:PSS (hydrogel) | 31 kPa | High for brain | [7] |

| Hydrogels | PVA/PAAm | 1 - 100 kPa | High for soft tissues | [6] |

| Elastomers | PDMS | 0.5 - 4 MPa | Moderate | [6] |

| Nanocomposites | PEDOT:PSS-PVA Hydrogel | 191 kPa | High for brain | [7] |

| Nanocomposites | Conductive Hydrogels | 2 - 31 kPa | High for soft tissues | [7] |

The data reveals that advanced bioelectronic materials can be engineered to closely match the mechanical properties of target tissues. Hydrogels and certain conductive polymer formulations achieve the kPa range required for neural interfaces, while moderately stiff elastomers in the MPa range may be suitable for peripheral applications.

Theoretical Frameworks for Conformability and Mechanical Integration

The ability of a bioelectronic device to conform to biological surfaces is governed by theoretical models that balance bending energy, adhesion energy, and tissue deformation. For rough surfaces like skin, theoretical models represent the surface as a sinusoidal profile and calculate the total energy of the conformal system as [3]:

Ūconformal = Ūbending + Ūskin + Ūadhesion

Where conformal attachment requires Ūconformal < 0. This model derives the conformability criterion for bioelectronics [3]:

πh²/γλ < 16/Eskin + λ³/π³EI

Where h represents wrinkle amplitude, λ represents wavelength, γ represents the skin-electronics interfacial energy coefficient, E_skin represents Young's modulus of the skin, and EI represents the effective bending stiffness of the bioelectronics.

For non-developable surfaces (with non-zero Gaussian curvature) like spherical organ surfaces, the conformability challenge increases. A model for mounting a circular thin film on a rigid sphere establishes the stability criterion for full conformability [3]:

Rf⁴/128Rs⁴ + h²/12(1-ν)Rs² ≤ λ/Eh

Where Rf and Rs are the radii of the film and sphere, h is film thickness, E is Young's modulus, ν is Poisson's ratio, and λ is the interfacial energy coefficient. This model indicates that optimal conformal attachment to spherical surfaces requires small size ratios, minimal thickness, and soft materials with low modulus [3].

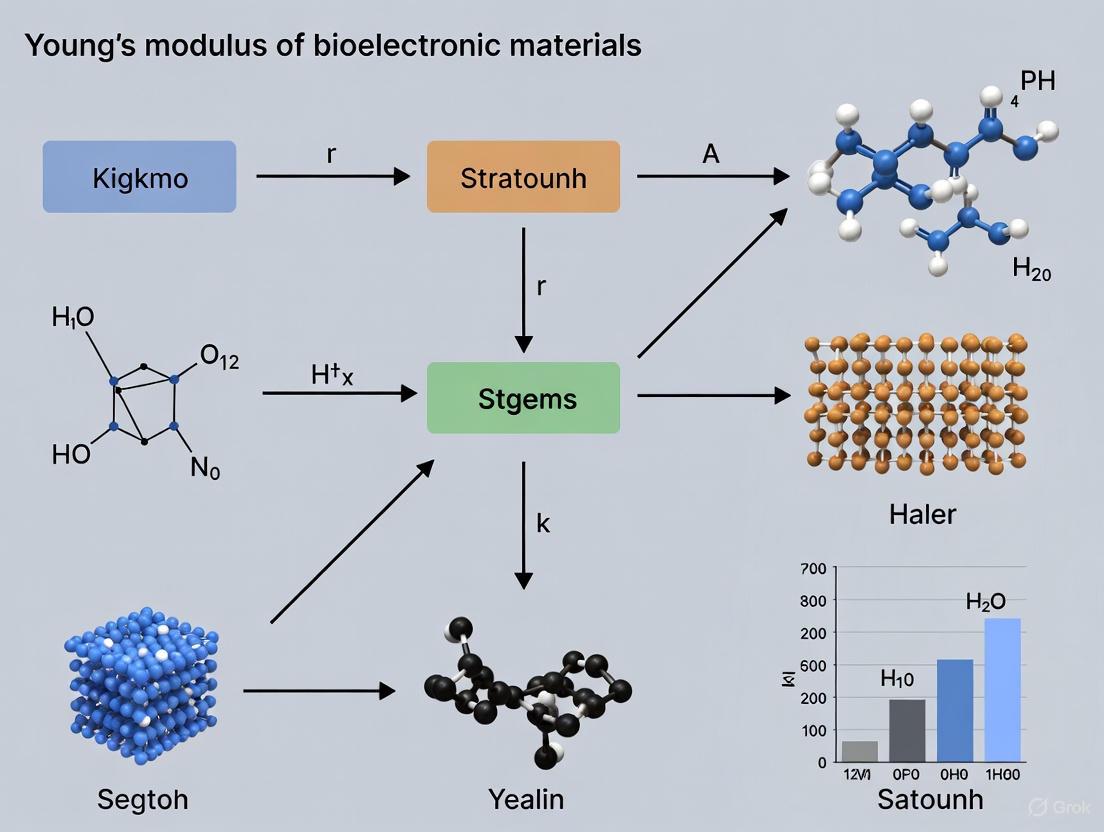

Diagram 1: Theoretical framework for bioelectronic conformability on biological surfaces, illustrating how material properties, surface geometry, and interfacial interactions determine interface stability.

Experimental Methodologies for Young's Modulus Characterization

Tensile Testing of Bulk Materials

The standard method for determining Young's modulus of bioelectronic materials involves uniaxial tensile testing, which provides direct stress-strain data for modulus calculation:

Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare dog-bone shaped specimens of standardized dimensions (e.g., ASTM D638) using solution casting, 3D printing, or microfabrication techniques

- Mounting: Secure the specimen in the tensile testing grips with careful alignment to avoid torsional stresses

- Testing Parameters: Apply uniaxial tension at a constant strain rate (typically 1-10 mm/min for soft materials) while measuring force and displacement

- Data Collection: Record stress (force/original cross-sectional area) and strain (change in length/original length) simultaneously

- Modulus Calculation: Determine Young's modulus as the slope of the initial linear portion of the stress-strain curve (typically 0-10% strain for elastic materials) [1] [2]

For highly compliant materials like hydrogels, specialized equipment with low-force load cells (0.1-10N range) is essential for accurate measurements. Environmental control may be necessary to maintain hydration during testing.

Nanoindentation for Thin Films and Biological Tissues

Nanoindentation provides localized mechanical characterization crucial for thin-film bioelectronic materials and biological tissues:

Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Mount thin films on rigid substrates or prepare tissue sections with minimal alteration to native mechanical properties

- Tip Selection: Choose appropriate indenter geometry (spherical tips for soft materials, Berkovich for stiffer materials)

- Testing Parameters:

- Apply controlled force or displacement sequences with precise spatial positioning

- Implement appropriate hold periods to account for viscoelastic relaxation

- Conduct multiple tests across different sample regions for statistical significance

- Data Analysis: Extract reduced modulus from force-displacement curves using Oliver-Pharr method, then calculate Young's modulus considering Poisson's ratio [6]

This technique is particularly valuable for characterizing the mechanical properties of conductive polymer coatings and hydrogel-based electrodes at biologically relevant length scales.

Electrical-Mechanical Correlation Measurements

Advanced characterization couples mechanical testing with electrical measurements to simulate operational conditions:

Protocol:

- Integrated Setup: Combine tensile testing apparatus with impedance analyzers or source-measure units

- Simultaneous Monitoring: Measure electrical properties (conductivity, impedance) while applying mechanical strain

- Cyclic Testing: Subject materials to repeated loading-unloading cycles to assess electromechanical durability

- Environmental Control: Conduct tests in physiologically relevant environments (aqueous solutions, 37°C) [7]

This approach provides critical insights into how the electrical functionality of bioelectronic materials withstands the mechanical deformations encountered in biological environments.

Diagram 2: Comprehensive workflow for Young's modulus characterization of bioelectronic materials, highlighting method selection based on material properties and application requirements.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Mechanically-Matched Bioelectronics

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Bioelectronic Interfaces

| Material Category | Specific Examples | Key Functions | Young's Modulus Range | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conductive Polymers | PEDOT:PSS, PANI, PPy | Electrode material, Conductive traces | 1 kPa - 1 GPa (tunable) | [7] |

| Hydrogel Matrices | PVA, PAAm, Gelatin, Alginate | Tissue-integration, Drug delivery | 1 - 100 kPa | [6] |

| Elastomers | PDMS, Ecoflex, SEBS | Substrate material, Encapsulation | 0.1 - 4 MPa | [6] |

| Conductive Nanofillers | Gold nanowires, Carbon nanotubes, Graphene | Enhancing conductivity, Mechanical reinforcement | Varies by composition | [6] |

| Dynamic Polymers | Polyelectrolytes, Stimuli-responsive polymers | Electrically tunable mechanical properties | Modulable via electric fields | [9] |

| Bioresorbable Materials | PLGA, PLA, Silk fibroin | Temporary implants, Reduced extraction surgery | 0.5 - 5 GPa | [4] |

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

Electrically Tunable Mechanical Properties

Recent research has revealed that certain polyelectrolyte materials exhibit electric field-dependent mechanical properties, opening possibilities for dynamically adjustable biointerfaces. Molecular dynamics simulations demonstrate that applied electric fields induce orientation changes in polyelectrolyte chains, enhancing attractive interactions between charged monomers and resulting in increased ultimate tensile stress and Young's modulus [9]. This electromechanical coupling enables materials that can dynamically adjust their stiffness in response to electrical stimuli, potentially allowing implants to optimize their mechanical properties for different physiological states.

Multifunctional Nanocomposites

The development of intrinsically stretchable conductive nanocomposites represents a paradigm shift in bioelectronic materials. By integrating conductive nanofillers (metal nanowires, carbon nanotubes, graphene) within soft polymeric matrices (elastomers, hydrogels), researchers have created materials that simultaneously achieve:

- Tissue-matching mechanical properties (Young's modulus: 1 kPa - 1 MPa)

- High electrical conductivity (>100 S/cm)

- Stretchability (>100% strain) [6]

These nanocomposites establish low-impedance conformal interfaces with tissues that are essential for high-fidelity biosignal recording and precise electroceutical interventions.

Closed-Loop Bioelectronic Systems

The integration of mechanically compliant interfaces with wireless technologies and artificial intelligence is enabling next-generation closed-loop therapeutic systems. These systems leverage conformable bioelectronics for continuous physiological monitoring, AI-driven analytics for signal interpretation and prediction, and responsive stimulation for precise therapeutic intervention [6]. The mechanical compatibility of the interface ensures long-term stability of the recording and stimulation capabilities essential for these autonomous systems.

Young's modulus has evolved from a fundamental material property to a critical design parameter in bioelectronic interfaces. The precise matching of mechanical properties between synthetic devices and biological tissues enables stable, long-term integration that is essential for advancing bioelectronic medicine. Through continued innovation in material synthesis, theoretical modeling, and characterization techniques, researchers are developing increasingly sophisticated bioelectronic systems that seamlessly merge with biological environments. The ongoing convergence of materials science, electrical engineering, and biology promises a future where bioelectronic interfaces become indistinguishable from the tissues they monitor and modulate, enabling unprecedented capabilities in healthcare and human enhancement.

A fundamental challenge in bioelectronic medicine is the profound mechanical mismatch between conventional electronic materials and the soft, dynamic tissues of the human body. This stiffness disparity, quantified by Young's modulus (a measure of material stiffness), poses significant barriers to long-term device functionality and biological integration [4]. Traditional electronic materials like silicon and metals possess Young's moduli in the gigapascal (GPa) range, creating orders of magnitude difference with biological tissues that typically exhibit moduli in the kilopascal (kPa) to megapascal (MPa) range [4] [10]. This mechanical mismatch triggers inflammatory responses, fibrotic encapsulation, and device failure through mechanisms including micromotion-induced damage and compromised signal fidelity [4] [8].

The field is consequently undergoing a paradigm shift from rigid to soft, flexible bioelectronic systems. As research advances, precise quantification of this "stiffness gap" becomes imperative for designing next-generation bioelectronic interfaces that seamlessly integrate with target tissues [10]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical analysis of Young's modulus values across biological tissues and electronic materials, details experimental methodologies for modulus characterization, and outlines material strategies to bridge this mechanical divide for enhanced therapeutic outcomes.

Quantitative Analysis of the Stiffness Gap

The mechanical properties of biological tissues and conventional electronics span several orders of magnitude. The following tables provide a comparative analysis of their Young's modulus values, highlighting the fundamental challenge in biointegration.

Table 1: Young's Modulus of Biological Tissues and Synthetic Mimics

| Material Category | Specific Material/Tissue | Young's Modulus | Measurement Context/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Tissues | Soft Tissues (general) | 1 kPa - 100 MPa [10] | Broad range encompassing various organs |

| Agar Gel (Tissue Mimic) | Adjustable based on concentration [11] | Used for its tunable, tissue-like mechanical properties | |

| Electronic Materials | Silicon | ~170 GPa [4] | Conventional semiconductor substrate |

| Metals (e.g., Copper, Gold) | >100 GPa [4] | Conventional wiring and electrodes | |

| Soft Electronic Materials | Polymers & Elastomers | 1 kPa - 1 MPa [4] | Typical range for soft bioelectronics |

| Gallium | 79.37 - 83.84 GPa [12] | Measured between -70°C and 20°C |

Table 2: Young's Modulus of Conventional vs. Soft Bioelectronic Materials

| Property | Rigid Bioelectronics | Soft & Flexible Bioelectronics |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Material Types | Silicon, metals, ceramics [4] | Polymers, elastomers, hydrogels, thin-film materials [4] |

| Young's Modulus | > 1 GPa [4] | 1 kPa – 1 MPa (typically) [4] |

| Bending Stiffness | > 10-6 Nm [4] | < 10-9 Nm [4] |

| Tissue Integration | Stiffness mismatch causes inflammation and fibrotic encapsulation [4] | Soft, conformal materials match tissue mechanics and reduce immune response [4] |

Experimental Protocols for Measuring Young's Modulus

Accurate characterization of mechanical properties is essential for developing compatible bioelectronic interfaces. The following section details standardized and emerging methodologies.

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) for Soft Tissues and Organoids

AFM is exceptionally valuable for measuring mechanical properties at the micro- and nanoscale, particularly for soft biological samples like organoids [13].

Protocol Summary: [13]

- Sample Preparation: Embed organoids in Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) compound and slice into sections using a cryostat to expose the surface for measurement.

- AFM Setup: Mount the sample and select an appropriate AFM probe (e.g., a spherical tip). Pre-calibrate the probe's spring constant.

- Force Mapping: Program the AFM to perform an array of force-distance curves across the sample surface. The probe approaches, indents, and retracts from the surface at each point.

- Data Analysis: Fit the retraction portion of the force-distance curve using a contact mechanics model (e.g., Hertz, Sneddon) to calculate the local Young's modulus based on the relationship between force and indentation depth.

Indentation Testing and Acoustic Impedance Correlation

For larger, hydrogel-based tissue mimics, a combination of macro-indentation and Scanning Acoustic Microscopy (SAM) provides an effective empirical approach.

Protocol Summary: [11]

- Sample Preparation: Prepare agar gels at various concentrations (e.g., 5% to 20%) to create a range of stiffnesses mimicking biological tissues.

- Acoustic Impedance Measurement: Use SAM to measure the local acoustic impedance (Z) across the sample surface. The acoustic impedance is derived from the reflection coefficient of high-frequency ultrasound.

- Mechanical Indentation Test: Perform indentation tests on the same samples using a mechanical tester to determine the apparent Young's modulus (E) from the force-displacement data.

- Empirical Correlation: Establish a power-law relationship between the measured acoustic impedance and Young's modulus (e.g., ( E = k \cdot Z^m )), which can then be used to estimate modulus from SAM data alone.

Non-Destructive Methods for Engineered Materials

Dynamic methods like the Impulse Excitation Technique (IET) and Ultrasonic (US) testing are crucial for characterizing fabricated materials without destruction.

Protocol Summary: [14]

- Impulse Excitation Technique (IET): A sample is lightly tapped to induce vibration. The fundamental resonant frequency ((ff)) is measured, and Young's modulus ((E)) is calculated using the formula: (E = 0.9465 \cdot (m ff^2 / b) \cdot (L^3 / t^3) \cdot T), where (m), (b), (L), and (t) are mass, width, length, and thickness, and (T) is a correction factor.

- Ultrasonic (US) Method: The speed ((VL)) of an ultrasonic wave traveling through a material is measured. Young's modulus is calculated using (E = VL^2 \cdot \rho \cdot (1+\nu)(1-2\nu)/(1-\nu)), where (\rho) is density and (\nu) is Poisson's ratio.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Developing bioelectronic devices with matched mechanical properties requires a specific set of functional materials.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Bioelectronics

| Category/Item | Function in Research | Specific Examples & Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Soft Substrates & Insulators | Provide flexible support and electrical insulation; dictate overall device modulus. | Parylene-C: Biocompatible, ultrathin films (<5 μm) for flexible OECTs [10]. PET: Polyethylene terephthalate, used for flexible multifunctional sensing platforms [10]. |

| Soft Conductors | Form stretchable interconnects and electrodes for signal transmission. | PEDOT:PSS: Conductive polymer, active layer in OECTs, compatible with flexible platforms [10]. Silver Nanowires: Used for creating transparent, flexible electrodes [10]. |

| Tissue Mimics & Phantoms | Serve as in vitro models for method development and testing. | Agar Gels: Tunable stiffness by concentration; used to simulate soft tissue mechanics [11]. |

| Stimuli-Responsive Materials | Enable shape-morphing and minimally invasive deployment of devices. | Hydrogels: Injectable, swellable, or moldable for deep tissue access and drug release [4] [10]. Dielectric Elastomers: Used in soft actuators for dynamic device positioning [15]. |

The quantification of the stiffness gap between biological tissues and conventional electronics provides a critical foundation for the future of bioelectronic medicine. The data and methodologies presented herein illuminate a clear path forward: the adoption of soft, flexible, and mechanically compliant materials is not merely an optimization but a necessity for stable long-term integration with the body [4] [10]. Emerging material strategies, including ultraflexible electronics, injectable meshes, and stimuli-responsive composites, are actively bridging this mechanical divide [15]. By prioritizing mechanical compatibility alongside electrical performance, researchers can overcome persistent biological challenges like the foreign body response [8] and unlock a new generation of high-fidelity, chronically stable bioelectronic therapies for a wide spectrum of diseases.

The seamless integration of bioelectronic devices with biological tissues is paramount for the advancement of personalized medicine, neural interfaces, and chronic health monitoring. The mechanical properties of these devices, particularly their stiffness (Young's modulus), play a defining role in their long-term performance and biocompatibility. Biological tissues, such as the brain, skin, and nerves, are intrinsically soft and dynamic, with Young's moduli typically ranging from 0.1 kPa to 100 kPa [4] [16]. In stark contrast, conventional electronic materials like silicon and metals possess moduli in the gigapascal range, creating a significant mechanical mismatch at the tissue-device interface [4] [17].

This mechanical mismatch is not a passive phenomenon; it initiates a cascade of adverse biological and technical consequences. When a rigid device is implanted or attached to soft tissue, the disparity in mechanical compliance leads to chronic inflammation, signal degradation, and ultimately, device failure. This whitepaper delves into the mechanisms underlying these failures, guided by the central thesis that matching the Young's modulus of bioelectronic materials to that of target tissues is a critical pathway toward achieving stable, long-lasting bioelectronic interfaces. The following sections will explore the consequences of mechanical mismatch, detail experimental methodologies for its investigation, and outline emerging material strategies that promise to bridge the mechanical divide.

The Triad of Failure: Consequences of Mechanical Mismatch

Chronic Inflammation and the Foreign Body Response

The body's reaction to a mechanically mismatched device is a primary obstacle to long-term bioelectronic stability. The innate immune system perceives the stiff, foreign object as a threat, triggering a Foreign Body Response (FBR). This response begins with an acute inflammatory phase, where immune cells like macrophages and microglia are activated and release inflammatory cytokines [18]. If the mechanical mismatch persists, this transitions into a chronic phase characterized by the formation of a glial scar in the central nervous system or a fibrotic capsule around peripheral implants [18] [19].

The core issue is that a rigid device constantly exerts stress on the surrounding compliant tissue, especially with the body's natural micromovements—from pulsations, breathing, or general motion. This chronic mechanical irritation sustains the inflammatory state. The resulting glial or fibrotic capsule acts as an insulating barrier, physically isolating the electrode from its target neurons and dramatically increasing the electrical impedance at the interface [18] [19]. This encapsulation is a direct biological consequence of the unresolved mechanical mismatch and is a major contributor to the decline in recording and stimulation efficacy over time.

Signal Degradation and Performance Loss

The biological encapsulation driven by mechanical mismatch directly undermines the primary function of a bioelectronic device: high-fidelity signal transmission. The consequences for signal quality are severe:

- Increased Electrical Impedance: The layer of scar tissue, which has poor electrical conductivity, increases the distance between the electrode and the target cells. This leads to a significant rise in interface impedance, which attenuates the small electrical signals from neurons before they can reach the recording electrode [18] [20].

- Reduced Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): Higher impedance correlates with increased thermal noise. This, combined with the signal attenuation from the fibrous capsule, makes it exceedingly difficult to distinguish faint, physiologically relevant signals from the electrical background noise, leading to a poor SNR [18].

- Stimulation Inefficiency: For stimulating electrodes, a higher impedance requires more voltage to deliver the necessary therapeutic current. This not only increases power consumption but also elevates the risk of inducing unwanted electrochemical reactions that can damage both the electrode and the surrounding tissue [18].

Over time, these factors can lead to a complete loss of usable signal, rendering the device ineffective for both diagnostic and therapeutic applications.

Mechanical and Material Failure Modes

Beyond the biological response, the mechanical mismatch itself can induce direct physical failure of the device. The constant strain and micromotion at the interface between a rigid device and soft tissue can lead to several failure modes [20] [19]:

- Material Fatigue: Repetitive stress cycles can cause cracking of brittle semiconductor substrates like silicon or delamination of thin-film metal traces.

- Insulation Failure: The polymer coatings used to insulate lead wires (e.g., polyimide, parylene) can degrade or crack under chronic mechanical strain, leading to electrical shorts or exposure of conductive surfaces.

- Strain Concentration at Interfaces: Finite Element Modeling (FEM) has shown that mechanical strain is often concentrated at the borders between different materials within a device, such as where a metal trace meets a silicon substrate. These areas become points of failure, with small protrusions being particularly vulnerable [20].

These abiotic failure mechanisms are a direct result of the device's inability to flex and move harmoniously with the tissue it interfaces with, ultimately leading to a loss of structural integrity and electronic function.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Mechanical Mismatch on Bioelectronic Performance

| Failure Mode | Primary Cause | Measurable Outcome | Typical Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foreign Body Response | Chronic irritation from stiff device | Glial scar formation; >50% increase in impedance [18] | Weeks to months |

| Signal Attenuation | Insulating fibrotic capsule | Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) degradation [18] | Months to years |

| Mechanical Fatigue | Cyclic strain & micromotion | Cracking of silicon shanks; delamination of traces [20] | Months to years |

| Stimulation Inefficiency | High interface impedance | Increased voltage requirement; risk of tissue damage [18] | Anytime post-encapsulation |

Investigating Mechanical Mismatch: Experimental Protocols and Characterization

A multi-faceted experimental approach is essential to understand and quantify the effects of mechanical mismatch. The following protocols represent key methodologies used in the field.

Protocol 1: Nanoscale Mechanical Characterization via Atomic Force Microscomy (AFM)

Objective: To measure the nanoscale Young's modulus and surface morphology of thin-film bioelectronic materials deposited on flexible substrates [21].

- Sample Preparation: Deposit the material of interest (e.g., Au, PEDOT:PSS) at varying thicknesses (e.g., 5 nm to 100 nm) onto a flexible substrate such as polyethylene terephthalate (PET) [21].

- AFM Setup: Utilize an atomic force microscope equipped with a calibrated cantilever probe. The force-distance curve mode is used to quantify the tip-sample interaction.

- Data Acquisition: Map the surface topography and acquire force-distance curves at multiple points across the sample surface. The slope of the retraction curve in the contact region is proportional to the Young's modulus.

- Data Analysis: Apply appropriate contact models (e.g., Hertzian, DMT) to the force-distance data to calculate the local Young's modulus. Compile data to create spatial maps of mechanical properties and correlate with film thickness.

Protocol 2: In Vivo Assessment of the Foreign Body Response

Objective: To evaluate the chronic inflammatory tissue response and recording performance of an implanted neural electrode.

- Device Implantation: Sterilize and surgically implant the neural probe (e.g., planar silicon electrode) into the target region of an animal model (e.g., mouse cortex) [20].

- Chronic Electrophysiology: Over a period of several months, regularly record neural signals (single-unit and multi-unit activity) and perform Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) to monitor changes in signal quality and interface impedance [20].

- Histological Analysis: At endpoint, perfuse and fix the brain. Section the tissue containing the implant track and stain for inflammatory markers (e.g., Iba1 for microglia, GFAP for astrocytes) and neuronal nuclei (NeuN).

- Correlative Analysis: Correlate the electrophysiological data (signal quality, impedance) with the histological evidence of glial scarring and neuronal loss around the implant site to establish a direct link between the FBR and performance degradation [20].

Theoretical Modeling of Conformability

Theoretical models provide a framework for designing devices that minimize mechanical mismatch. For instance, the conformability of a thin-film device on a rough surface (like skin) can be modeled by considering the total energy of the system: ( {\bar{U}}{\text{conformal}}={\bar{U}}{\text{bending}}+{\bar{U}}{\text{skin}}+{\bar{U}}{\text{adhesion}} ), where the terms represent the bending energy of the device, the elastic energy of the skin, and the interfacial adhesion energy, respectively. A conformal attachment is achieved when ( {\bar{U}}_{\text{conformal}} < 0 ) [3]. For non-developable surfaces (with non-zero Gaussian curvature like a sphere), models show that to achieve stable conformal attachment, a device should have a small size, minimal thickness, and a low Young's modulus [3].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for analyzing mechanical mismatch. The approach combines nanoscale material characterization, in vivo biological response assessment, and theoretical modeling to form a comprehensive understanding.

Material Strategies for Mechanical Harmony

To mitigate the consequences of mechanical mismatch, the field is shifting from rigid to soft and compliant materials. The goal is to develop devices with a bending stiffness below 10⁻⁹ Nm, contrasting sharply with the >10⁻⁶ Nm of conventional rigid electronics [4]. Key material strategies include:

Conducting Polymer Hydrogels

Materials like PEDOT:PSS hydrogels represent a promising frontier. They can be engineered to achieve a full spectrum of moduli (0.28 kPa to 15 kPa) that match various soft tissues, while maintaining high electrical conductivity (1.99 S/m to 5.25 S/m) [16]. Their mixed ionic-electronic conductivity facilitates efficient charge transfer with biological tissue. When used as electrodes, these hydrogels provide a stable interface for recording electromyogram (EMG), electrocardiogram (ECG), and electroencephalogram (EEG) signals with SNRs as high as 20.0 dB, outperforming traditional rigid electrodes [16].

Ultrathin and Flexible Metallic Films

Even conventional metals like gold can be made more compliant through geometric design. Research shows that Au films thinner than 10 nm fail to form a continuous conductive layer, while films thicker than 25 nm on PET substrates maintain reliable conductivity and mechanical stability under bending conditions [21]. The use of ultrathin substrates (e.g., 1.4 μm PET films) drastically reduces bending stiffness, allowing devices to achieve conformal contact with curved surfaces through van der Waals forces alone, without aggressive adhesives [10].

Textile and Nanostructured Composites

Integrating conductive nanomaterials like carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and graphene into electrospun nanofibers creates pressure-sensitive, breathable, and highly flexible sensing networks [10]. These composite structures can achieve conformal contact over large areas (e.g., 9 × 9 cm²), enabling applications like full-body motion sensing and health monitoring [10].

Table 2: Material Solutions for Mitigating Mechanical Mismatch

| Material Class | Example Materials | Young's Modulus Range | Key Advantages | Validated Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conducting Polymer Hydrogels | PEDOT:PSS with modifiers [16] [22] | 0.28 kPa – 15 kPa [16] | Tissue-matched softness, mixed ionic-electronic conduction | SNR up to 20.0 dB for EEG/ECG/EMG [16] |

| Ultrathin Metallic Films | Au on PET [21] | N/A (Bending stiffness reduced) | High conductivity, established fabrication | Stable conductivity on PET when >25nm thick [21] |

| Nanostructured Composites | CNT/Graphene-PET nanofibers [10] | N/A (Geometric flexibility) | Breathability, large-area conformity | >90% transmittance, bending-insensitive pressure sensing [10] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Bioelectronic Interface Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Specific Example & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Flexible Substrates | Provides a soft, bendable base for device fabrication. | Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET): Excellent optical and thermal properties; allows creation of ultrathin (<1.4 μm) devices for conformal contact [21] [10]. |

| Conductive Polymers | Forms soft, electroactive layers for recording and stimulation. | PEDOT:PSS: Offers high conductivity and biocompatibility; can be modified into hydrogels for tissue-matched modulus [16] [22]. |

| Nanostructured Coatings | Increases electroactive surface area to lower impedance. | Iridium Oxide (SIROF) & Platinum Nanograss: Coating electrodes with these materials drastically increases surface area, reducing impedance and improving charge injection capacity [18]. |

| Anti-inflammatory Coatings | Modulates the biological interface to suppress the FBR. | Dexamethasone-eluting coatings: Locally releases anti-inflammatory drugs to suppress acute immune response post-implantation [18]. |

| Hydrogel Matrices | Mimics the extracellular matrix, improving biocompatibility. | Zwitterionic Hydrogels: Provide a hydrating, neutrally charged interface that resists non-specific protein adsorption, reducing inflammation and enabling long-term (≥4 weeks) stable implantation [22]. |

The evidence is conclusive: a significant mechanical mismatch between bioelectronic devices and biological tissues leads to a detrimental triad of chronic inflammation, signal degradation, and device failure. The rigid nature of conventional electronics incites a foreign body response, resulting in an insulating glial or fibrotic capsule that isolates the device and increases electrical impedance. Concurrently, mechanical strain and micromotion induce material fatigue and structural failure in the device itself.

The path forward, central to modern bioelectronic materials research, is the development of devices that achieve mechanical and electrical harmony with biology. This involves the adoption of soft, compliant materials such as conducting polymer hydrogels, ultrathin geometric designs, and nanostructured composites. These strategies aim to reduce bending stiffness to levels compatible with soft, dynamic tissues. Future research must continue to refine these material systems, focusing on their long-term stability, reliable fabrication, and seamless integration with wireless power and data transmission systems. By prioritizing the matching of Young's modulus, the field of bioelectronics can move beyond simply avoiding failure and toward creating truly stable, high-fidelity interfaces that unlock their full therapeutic and diagnostic potential.

The evolution of bioelectronic medicine hinges on the development of devices that can seamlessly integrate with biological tissues for long-term diagnostic monitoring and therapeutic intervention. A critical determinant of this integration is the mechanical compatibility between the implantable device and the host tissue, primarily governed by the material property known as Young's modulus, a measure of stiffness or elastic resistance to deformation [23]. The pervasive challenge in biointerface design is the significant mechanical mismatch between conventional electronic materials, which are often rigid, and soft, dynamic biological tissues [10] [4] [5]. This mismatch induces chronic inflammation, fibrotic encapsulation, and device failure, ultimately compromising the long-term stability and functionality of the interface [24] [23].

This whitepaper synthesizes current research to define the target Young's modulus values for stable interfaces with neural, cardiac, and skin tissues. Framed within the broader context of materials science for bioelectronics, it provides a foundational guide for researchers and engineers aiming to design next-generation bioelectronic devices with enhanced biocompatibility and chronic stability.

Fundamental Principles of Mechanical Matching at Biointerfaces

The human body is composed of soft, dynamic tissues that undergo continuous movement and deformation. The Young's modulus of common bioelectronic materials and target tissues spans several orders of magnitude, creating a fundamental design challenge.

Foreign Body Response (FBR) and Fibrosis: When a rigid implant is introduced into soft tissue, the mechanical mismatch creates sustained stress at the interface. This perceived injury activates immune cells, leading to a cascade of events: activation of microglia and astrocytes in the brain, proliferation of fibroblasts in peripheral tissues, and the eventual deposition of collagen and other extracellular matrix components to form a dense, fibrotic capsule around the device [24] [23] [25]. This capsule acts as an insulating layer, increasing impedance for recording electrodes and reducing the efficiency of stimulating electrodes, thereby degrading signal fidelity over time [24] [23].

The "Mechanical Invisibility" Paradigm: The optimal strategy to mitigate FBR is to design devices that are mechanically "invisible" to the host immune system [24]. This involves engineering devices whose bending stiffness (a product of Young's modulus and the geometric moment of inertia) and effective modulus closely match those of the surrounding tissue. For implants, this minimizes relative micromotion and chronic stress, while for wearables, it ensures conformal contact and comfort, reducing motion artifacts [24] [10].

Quantifying Bending Stiffness: The bending stiffness of an electrode shaft is a critical parameter for penetrating implants. For a simple rod electrode with a circular cross-section, it is given by: ( EI = E \frac{\pi r^4}{4} ) where (E) is Young's modulus and (r) is the radius [24]. This formula highlights that reducing the device's cross-sectional area (miniaturization) is as crucial as selecting a low-modulus material for achieving tissue-like flexibility.

The diagram below illustrates the critical relationship between material properties, device design, and the ultimate biological and functional outcomes at the biointerface.

Target Tissues and Ideal Material Properties

The mechanical properties of target tissues vary significantly, necessitating tailored approaches for interface design. The table below summarizes the target Young's modulus ranges for key application areas.

Table 1: Target Young's Modulus Values for Bioelectronic Interfaces

| Target Tissue/Interface | Tissue Young's Modulus | Target Device Modulus | Key Design Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neural Tissue (Brain) | 1–10 kPa [24] [23] [5] | ~1–100 kPa [23] [25] [5] | Minimize bending stiffness for penetrating electrodes; use ultra-flexible, sub-μm thick substrates for cortical surface electrodes. |

| Cardiac Tissue | Information not explicitly stated in search results | Information not explicitly stated in search results | Requires elastic, flexible, and conductive materials to withstand continuous cyclic strain from heartbeats [26]. |

| Skin Interface | Information not explicitly stated in search results | < 1 MPa (for conformal contact) [10] | Ultralow bending stiffness (< 10⁻⁹ N·m) for conformal adhesion via van der Waals forces; stretchability to accommodate joint movement [10]. |

| Conventional Rigid Electronics | — | Silicon: ~10² GPaPlatinum: ~10² MPa [23] | Significant mechanical mismatch with all soft tissues, leading to chronic inflammation and device failure. |

Neural Interfaces

The brain is exceptionally soft, with a Young's modulus of approximately 1–10 kPa [24] [23] [5]. Conventional rigid electrodes, such as those made from silicon (≈10² GPa) or platinum (≈10² MPa), are orders of magnitude stiffer, causing significant mechanical mismatch [23].

Deep Brain Flexible Electrodes: The ideal strategy involves using flexible materials with a low Young's modulus, combined with geometric miniaturization, to reduce bending stiffness. This allows the electrode to mimic the softness of brain tissue, reducing chronic inflammation and the formation of glial scars [24]. For example, filamentary electrodes with widths as small as 7 μm and thicknesses of 1.5 μm have been developed to achieve a cross-sectional area at the subcellular level, minimizing acute injury during implantation and chronic micromotion thereafter [24].

Flexible and Injectable Platforms: Beyond penetrating probes, there is a push toward flexible patch-type electrodes for cortical surface mapping and injectable mesh electronics. These devices leverage ultra-thin polymer substrates (e.g., parylene-C, polyimide) with thicknesses often below 10 μm, resulting in a bending stiffness so low that they can conform to the cortical surface without causing significant irritation [10] [5]. The goal is to achieve an effective modulus that falls within the ~1–100 kPa range to ensure mechanical compatibility with the brain [25] [5].

Cardiac Interfaces

While the search results do not provide a specific Young's modulus value for cardiac tissue, they emphasize that the heart is a dynamic, contractile organ. Therefore, materials for cardiac interfaces must be not only flexible but also elastic and stretchable to withstand continuous cyclic strain [26].

- Conductive Biomaterials: Cardiac tissue engineering often employs conductive biomaterials that mimic the native extracellular matrix. These materials need to support electrical signal propagation between cardiomyocytes while matching the mechanical properties of the myocardium. Typical strategies use biodegradable elastomeric polymers, often in composite form with conductive nanomaterials like carbon nanotubes or gold nanowires, to create scaffolds that are both electrically conductive and mechanically compliant [26].

Skin Interfaces

The skin is the primary interface for wearable bioelectronics. Its modulus varies by location, but the key to a stable, high-fidelity interface is achieving conformal contact over large, curvilinear areas, often under dynamic motion [10].

Ultralow Bending Stiffness: The primary design parameter is bending stiffness rather than Young's modulus alone. By using ultrathin (< 1–10 μm) device geometries, even materials with a moderately high modulus (like polyimide or PET) can achieve bending stiffness low enough for conformal, van der Waals-driven adhesion to the epidermis without external adhesives [10]. This minimizes motion artifacts and improves signal quality for long-term electrophysiological monitoring (ECG, EMG, EEG) [27] [10].

Mechanically Adaptive Materials: Innovative strategies include modulus-adjustable materials. For instance, dry microneedle electrodes (MNEs) made from shape memory polymers (SMPs) can be stiff at room temperature for skin penetration and then soften at body temperature to match the mechanics of the surrounding skin tissue, thereby minimizing invasiveness and improving comfort during long-term use [27].

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Biointerfaces

Protocol: Nanoscale Mechanical Characterization of Flexible Electrodes

This protocol outlines the procedure for measuring the Young's modulus of thin-film conductive layers used in flexible electronics, as demonstrated in studies on gold films [21].

- Sample Preparation: Deposit the material of interest (e.g., Gold) onto a flexible substrate (e.g., Polyethylene Terephthalate, PET) using standard deposition techniques like sputtering or evaporation. Prepare samples with a range of thicknesses (e.g., 5 nm to 100 nm) [21].

- Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) Indentation:

- Use an AFM system equipped with a calibrated cantilever and a sharp tip.

- Engage the tip with the sample surface and obtain force-distance curves at multiple locations across the sample.

- The slope of the force-distance curve in the contact region is related to the sample's Young's modulus.

- Data Analysis: Fit the retraction curve of the force-distance data to an appropriate contact mechanics model (e.g., Hertzian, DMT, or JKR models) to extract the local Young's modulus value. Compile results from multiple measurements to report an average and standard deviation [21].

- Correlative Electrical Measurement: Simultaneously or subsequently, measure the electrical resistance of the film under flat and bent conditions to correlate mechanical flexibility with electrical performance [21].

Protocol: In Vivo Assessment of Foreign Body Response

This protocol describes a standard method for evaluating the biocompatibility and chronic stability of a neural implant.

- Device Implantation: Sterilize the neural interface device. Under approved animal care protocols, anesthetize the animal and stereotactically implant the device into the target brain region (e.g., motor cortex, hippocampus) [24] [23].

- Chronic Electrophysiological Recording: Over a period of weeks to months, periodically record neural signals (e.g., single-unit activity, local field potentials) from the implant. Key metrics include signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), spike amplitude, and recording stability [24] [5].

- Impedance Spectroscopy: Regularly measure the electrode-electrolyte impedance, typically at 1 kHz. A gradual increase in impedance often correlates with the formation of a fibrotic, insulating scar tissue around the electrode [24] [23].

- Histological Analysis (Endpoint): At the end of the study, perfuse the animal and extract the brain.

- Tissue Sectioning: Cryosection the brain tissue containing the implant track into thin slices.

- Staining: Perform immunohistochemical staining for specific cell markers:

- Imaging and Quantification: Use fluorescence or confocal microscopy to image the stained tissue. Quantify the intensity and thickness of the glial scar and the density of neurons within a defined radius (e.g., 100 μm) from the implant interface [23].

The workflow for the comprehensive in vivo assessment of a bioelectronic interface is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Developing bioelectronic interfaces with tailored Young's modulus requires a specific set of materials and reagents. The following table details key components used in the field.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Biointerface Development

| Material/Reagent | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS | Conductive polymer; provides high electrical conductivity and ionic/electronic coupling while maintaining mechanical softness [27] [25]. | Coating for microneedle electrodes and cortical surface arrays to achieve low impedance and high-fidelity recording [27]. |

| Shape Memory Polymers (SMPs) | Substrate material with modulus-adjustable properties; stiff for implantation, soft at body temperature to minimize mismatch [27]. | Core material for mechanically adaptive dry microneedle electrodes (MDMEs) for skin and brain interfaces [27]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) & Graphene | Carbon-based nanomaterials; used as conductive fillers in composites to impart electrical conductivity and strength to soft polymers [26] [25]. | Creating conductive, flexible cardiac patches and fiber-based neural interfaces [26] [25]. |

| Polyimide (PI) & Parylene-C | Flexible, biocompatible polymer substrates; provide electrical insulation and structural support with low bending stiffness [24] [10]. | Substrate for ultraflexible, conformal epidermal electronic devices and implantable neural probes [24] [10]. |

| Liquid Metals (e.g., EGaIn) | Highly conductive and stretchable conductor; maintains conductivity under extreme deformation [25]. | Stretchable interconnects in wearable and implantable devices that require large strain tolerance [25]. |

| Gold (Au) Thin Films | Conductive metal layer; offers excellent conductivity and stability, with flexibility achievable at sub-micron thicknesses [21]. | Electrode material on flexible PET substrates for skin-worn electrodes; optimal conductivity is achieved with films >25 nm thick [21]. |

Achieving a stable, long-term bioelectronic interface is fundamentally an exercise in mechanical engineering at the soft-soft material boundary. The ideal target for Young's modulus in bioelectronic devices is unequivocally in the kPa to low MPa range, closely mirroring the mechanical properties of the host tissue. For the brain, this means striving for devices with moduli of 1–100 kPa, while for skin interfaces, achieving an ultralow bending stiffness through geometric thinning is paramount.

Future advancements will likely focus on several key areas:

- Multimodal and 3D Interfaces: The integration of electrical, optical, and chemical functionalities into a single, mechanically compliant device will provide a more comprehensive toolkit for neuroscience and cardiac research [5].

- Advanced Materials: The exploration of novel composites, liquid metals, and fully biodegradable conductive polymers will further close the mechanical and functional gap between electronics and biology [25].

- Intelligent Interfaces: The development of "living" bioelectronics that can adapt, self-heal, and even promote neural regeneration represents the next frontier, promising interfaces that are not only mechanically invisible but also biologically integrated [5].

By adhering to the principle of mechanical matching, researchers can overcome a significant barrier to chronic device reliability, accelerating the translation of bioelectronic technologies from the laboratory to the clinic.

Material Innovations and Fabrication Techniques for Modulus-Matched Bioelectronics

The development of bioelectronic devices for seamless integration with biological tissues represents a frontier in medical science. A central challenge in this field is the profound mechanical mismatch between conventional electronic materials and soft biological structures. Traditional electronic materials, such as silicon and metals, possess elastic moduli in the range of 10-200 GPa [28]. In stark contrast, biological tissues, including skin, neural tissue, and organs, are soft and elastic, typically exhibiting Young's modulus values of 1-100 kPa [28]. This discrepancy of approximately six orders of magnitude leads to significant strain concentration at the biotic-abiotic interface, causing mechanical damage, impaired signal transduction, chronic inflammation, and eventual device failure [28]. Consequently, there is a critical need for materials that simultaneously achieve tissue-like softness and electronic functionality.

Conductive hydrogels have emerged as a promising class of materials to address this challenge. These materials combine the tuneable mechanical properties of hydrogels with the electrical conductivity necessary for bioelectronic applications [29] [30]. By precisely engineering their composition and structure, researchers can create hydrogel-based materials with Young's modulus values that closely match those of target tissues while maintaining sufficient conductivity for applications such as biosensing, electrical stimulation, and drug delivery [28] [31]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical overview of the material strategies, properties, and characterization methods for developing hydrogel-based materials with tissue-like softness and conductivity, framed within the context of Young's modulus considerations for bioelectronic integration.

Material Systems and Conduction Mechanisms

Conductive hydrogels achieve their electrical properties through various mechanisms and material compositions. The three primary approaches include the incorporation of conductive fillers, use of intrinsically conductive polymers, and exploitation of ionic conductivity.

Conductive Filler-Based Systems

These systems incorporate conductive nanomaterials within hydrogel matrices to create percolating conductive networks:

- Carbon-Based Materials: Graphene and carbon nanotubes offer high conductivity but often require high loading levels that compromise mechanical properties. A novel approach using pristine graphene at oil-water interfaces creates self-assembled percolating networks within hydrogels, achieving conductivities up to 15 mS/m with minimal filler content [32].

- Metal-Based Nanomaterials: Silver and gold nanowires provide excellent conductivity but may present cytotoxicity concerns and higher costs [29].

- Liquid Metals: Materials like gallium-based alloys offer unique combinations of conductivity and fluidity, enabling stretchable conductive pathways [29].

Intrinsically Conductive Polymer Hydrogels

These systems utilize conductive polymers as the primary hydrogel matrix or as integrated components:

- PEDOT-Based Systems: Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) variants are widely used, including PEDOT:PSS, PEDOT:CHC, and novel alternatives like PEDOT:DBSA, which offers improved biocompatibility with Young's modulus values matching soft tissues (0.5-5 kPa) [33] [34] [31].

- Other Conductive Polymers: Polyaniline (PANI) and polypyrrole (PPy) provide alternative conductive platforms with different mechanical and electrochemical properties [30].

Ionic Conductive Hydrogels

These systems rely on ion transport through hydrated networks, typically offering lower conductivity but superior transparency and mechanical matching with extremely soft tissues [30].

Table 1: Conduction Mechanisms in Hydrogel-Based Materials

| Conduction Type | Mechanism | Advantages | Conductivity Range | Young's Modulus Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic (Filler-Based) | Electron transport through percolating networks | High conductivity, Stability | 0.1-15 mS/m [32] | 1-100 kPa [32] |

| Electronic (Polymer-Based) | Electron transport along conjugated polymer chains | Homogeneous structure, Tunability | 1-1000 S/m [31] | 0.5-5 kPa [31] |

| Ionic | Ion migration through hydrated pores | High transparency, Excellent softness | 0.01-1 S/m [30] | 0.1-10 kPa [30] |

Quantitative Properties of Hydrogel Material Systems

The mechanical and electrical properties of conductive hydrogels vary significantly based on their composition and structural design. The following table summarizes key parameters for prominent material systems reported in recent literature.

Table 2: Mechanical and Electrical Properties of Conductive Hydrogel Systems

| Material System | Young's Modulus | Conductivity | Tensile Strain | Key Features | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:DBSA Hydrogel | Matches soft tissues | Sufficient for cell stimulation; Low impedance at 1 Hz | High flexibility | Pure conductive hydrogel, excellent biocompatibility | [31] |

| PEDOT:CHC/Silk (1:1) | Optimal mechanical properties | Electrically programmable | Exceptional resilience | >90% drug loading, hierarchical architecture | [33] [34] |

| Graphene/PHMA Foam | Tunable via composition | Up to 15 mS/m | Flexible foam structure | Self-assembled percolating network, minimal filler | [32] |

| Fe³⁺-Gelatin/P(AAc-co-AAm) | Tunable via Fe³⁺ concentration | Tunable conductivity | 569% elongation | Dynamic cross-linking, self-healing capability | [28] |

| GL-PVA-Gelatin | 3.18× increase with 50% GL | Not specified | Balanced elasticity | Dual-network, hydrogen bonding enhancement | [28] |

Fabrication and Experimental Methodologies

Granular Hydrogel Fabrication for Injectable Bioelectronics

Granular hydrogels represent an emerging approach for creating injectable or printable conductive materials. The following workflow illustrates the fabrication process for PEDOT:PSS microparticles and their assembly into functional bioelectronic components:

Diagram 1: Granular hydrogel fabrication workflow (3 steps)

Detailed Protocol:

- Emulsion Preparation: Create a water-in-oil emulsion by adding aqueous PEDOT:PSS solution to an oil phase with vigorous stirring. The two-phase system resembles an "oil-and-vinegar salad dressing" [35].

- Crosslinking: Heat the emulsion to crosslink the polymer, forming stable spherical hydrogel microparticles. Temperature and duration control particle size and mechanical properties.

- Assembly: Pack microparticles tightly to create a granular hydrogel material. The particles maintain micropores between them while flowing like liquids when force is applied [35].

- Application: Extrude through needles or 3D printing nozzles to create customized electrode structures that can conform to topographically diverse biological surfaces [35].

Hierarchical Conductive Polymer Hydrogel Synthesis

For more structured hydrogel systems with enhanced drug loading capacity, hierarchical architectures can be created:

PEDOT:CHC/Silk Hydrogel Fabrication [33] [34]:

- CHC Synthesis: Carboxymethyl-hexanoyl chitosan (CHC) is synthesized through chemical modification of chitosan to create an amphiphilic polymer with self-assembly capabilities.

- PEDOT:CHC Formation: Dissolve 0.2 mg CHC in 50 mL distilled water at 50°C until completely dissolved. Add 1.7 mL EDOT monomer and stir for 30 minutes. Add 5 mL FeCl₃·6H₂O oxidant solution to initiate polymerization. React for 24 hours, then purify the resulting PEDOT:CHC.

- Hierarchical Structure Formation: PEDOT:CHC self-assembles into hollow microgel structures driven by thermodynamic forces to minimize surface energy.

- Silk Integration: Blend PEDOT:CHC with silk fibroin solution at varying ratios (optimally 1:1) to form interpenetrating networks that provide mechanical reinforcement while maintaining electroactivity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful development of conductive hydrogels requires specific materials and characterization approaches. The following table outlines key reagents and their functions in creating and optimizing these materials.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Conductive Hydrogel Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application | Key Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS | Conductive polymer | Granular hydrogels, Composite electrodes | Biocompatibility, Mixed ionic-electronic conduction [35] |

| PEDOT:DBSA | Conductive polymer | Pure conductive hydrogels | Tunable mechanical properties, Low impedance [31] |

| Silk Fibroin | Structural biopolymer | Hierarchical hydrogels, Mechanical reinforcement | Biocompatibility, Mechanical strength, Crystalline structure [33] |

| CHC (Carboxymethyl-Hexanoyl Chitosan) | Amphiphilic dopant | Drug-eluting hydrogels | Self-assembly, High drug encapsulation (>90%) [33] [34] |

| Pristine Graphene | Conductive filler | Porous hydrogel foams | High conductivity, Self-assembling percolation networks [32] |

| Fe³⁺ Ions | Dynamic crosslinker | Mechanically tunable hydrogels | Ionic coordination, Redox activity, Self-healing [28] |

| Glycerol (GL) | Binary solvent component | Dual-network hydrogels | Hydrogen bonding, Mechanical enhancement [28] |

Advanced Applications in Bioelectronics

Programmable Drug Delivery for Diabetic Wound Healing

Conductive hydrogels enable electrically-triggered drug release systems for advanced wound care. The following diagram illustrates the operational mechanism of a hierarchical PEDOT:CHC/silk hydrogel for diabetic wound treatment:

Diagram 2: Electrically-triggered drug release mechanism (5 steps)

System Optimization Parameters [33] [34]:

- Electrical Stimulation Parameters: Voltage (0.5-3V), frequency (0.1-100 Hz), waveform (DC, pulsed), and duration can be systematically optimized to achieve precise spatiotemporal control of drug release.

- Electrode Geometry: Interdigitated electrode arrays improve field distribution and release control compared to simple planar electrodes.

- Material Composition: The PEDOT:CHC to silk ratio (optimally 1:1) balances mechanical resilience (>90% drug encapsulation efficiency) with electrochemical responsiveness.

Tissue-Integrated Sensors and Stimulators

Granular conductive hydrogels enable novel biointegration approaches:

- Conformal Contact: Injectable granular hydrogels can spread over tissues or encapsulate cells, enabling continuous monitoring of biological activity [35].

- In Vivo Validation: Researchers have successfully measured local field potentials corresponding to odor sensing in locust antennae using PEDOT:PSS granular hydrogels [35].

- Customizable Electrodes: 3D printing capability allows creation of patient-specific electrode geometries that match individual anatomical features [35].

Hydrogel-based materials with tissue-like softness and conductivity represent a transformative approach to bioelectronic integration. By precisely engineering material composition, structure, and conduction mechanisms, researchers can create systems with Young's modulus values that closely match biological tissues (1-100 kPa) while maintaining sufficient electrical functionality for sensing, stimulation, and drug delivery applications. Continued advancement in this field requires multidisciplinary approaches that combine materials science, electrical engineering, and biological expertise to address remaining challenges in long-term stability, manufacturing scalability, and clinical translation. The development of standardized characterization protocols specifically tailored for soft, hydrated conductive materials will further accelerate progress in this rapidly evolving field.

The field of bioelectronics has been fundamentally reshaped by the development of conductive polymers (CPs) and their nanocomposites, which uniquely blend the electronic functions of semiconductors with the mechanical properties of plastics. The discovery of conductive polyacetylene in 1977, recognized by the 2000 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, marked the birth of this material class and opened avenues for organic electronic materials with biomedical potential [36] [37]. Unlike traditional metals and inorganic semiconductors, conductive polymers offer electronic-ionic hybrid conductivity, mechanical softness, and versatile chemical modification capabilities, making them ideally suited for bio-interfacing applications [38]. Their relevance to Young's modulus research in bioelectronics is paramount: these materials can be engineered to match the mechanical properties of biological tissues, thereby minimizing mechanical mismatch at the tissue-implant interface—a critical factor in reducing chronic inflammation and improving long-term device performance [38] [39] [37].

The fundamental structure enabling conductivity in these polymers is a conjugated molecular backbone consisting of chains of alternating single and double bonds, which facilitates electron delocalization through overlapping p-orbitals [38]. Their conductivity can be significantly enhanced through doping, which generates charge carriers (polarons and bipolarons) within the polymer structure [40]. This unique combination of properties has positioned conductive polymers as transformative materials for a new generation of flexible, stretchable, and implantable bioelectronic devices.

Material Properties and Characterization

Key Conductive Polymers and Their Properties

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of Major Conductive Polymers

| Polymer | Electrical Conductivity Range | Key Properties | Primary Applications in Bioelectronics |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS | 1–104 S·cm⁻¹ (standard); up to ~8800 S·cm⁻¹ with advanced processing [39] | High conductivity, transparency, flexibility, intrinsic stretchability, air stability [41] | Neural electrodes, wearable sensors, organic electrochemical transistors [39] [37] |

| Polyaniline (PANI) | 10−2–100 S·cm⁻¹ (emeraldine salt) [41] | Tunable conductivity, environmental stability, ease of synthesis, pH-dependent properties [36] [41] | Biosensors, corrosion protection, energy storage devices [36] [40] |

| Polypyrrole (PPy) | Variable with doping; can achieve high conductivity [41] | Good environmental stability, high conductivity, redox properties, biocompatibility [36] [41] | Neural interfaces, drug delivery systems, biosensors [36] [38] |

| Polyacetylene (PA) | 104–105 S·cm⁻¹ when doped [41] | High conductivity when doped, photoconductivity, gas permeability [41] | Limited due to instability; historical significance [41] |

Mechanical Properties and Young's Modulus Considerations

The Young's modulus of conductive polymers is a critical parameter in bioelectronics, as mechanical mismatch with soft biological tissues can lead to fibrotic encapsulation and device failure [38]. Traditional metallic electrodes like platinum and gold have modulus values in the GPa to TPa range, while neural tissue has a modulus of approximately 0.1-1 kPa [38]. Conductive polymers help bridge this gap:

- PEDOT:PSS can be processed to achieve tissue-mimetic softness while maintaining high conductivity [39]. Recent advances in vertically phase-separated PEDOT:PSS films demonstrate simultaneous achievement of high conductivity (>8500 S·cm⁻¹) and enhanced biointerface interactions [39].

- Conductive elastomers developed by embedding PEDOT nanowires in polyurethane matrices create fully polymeric electrode materials with tunable mechanical properties, though increasing nanowire content typically increases Young's modulus while decreasing strain at failure [42].

- Conductive hydrogels (CHs) and conductive polymeric hydrogels (CPHs) provide exceptional flexibility, tensile strength, and biocompatibility, making them ideal for electrical devices interfacing with biological systems [36].

Table 2: Mechanical and Electrical Properties of Conductive Materials for Bioelectronics

| Material Type | Young's Modulus Range | Electrical Conductivity Range | Advantages for Biointerfacing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metals (Pt, Au) | GPa to TPa range [38] | ~105 S·cm⁻¹ [37] | Excellent conductivity, long-term stability | High stiffness causes mechanical mismatch |

| Conductive Polymers (PEDOT:PSS) | kPa to MPa range (tunable) [38] [39] | 1–8800 S·cm⁻¹ [39] | Soft, flexible, tissue-matching modulus | Stability challenges under physiological conditions |

| Conductive Elastomers | kPa to MPa range (tunable with filler loading) [42] | Variable with composition | Fully polymeric, compliant mechanics | Conductivity typically lower than pure metals |

| Biological Tissues | 0.1–1 kPa (neural tissue) [38] | Ionic conduction | Native environment | - |

Fabrication and Processing Methodologies

Synthesis Techniques for Conductive Polymers

The synthesis of conductive polymers can be achieved through various methods, each offering distinct advantages for bioelectronic applications:

Chemical Polymerization: This scalable, economical approach uses oxidizing agents such as ammonium persulfate or enzymatic catalysts to initiate polymerization [40]. The mechanism involves oxidation of monomer units to form radical cations, which combine to form dimers and eventually polymer chains [40]. Enzymatic polymerization using peroxidase or laccase offers milder, more environmentally friendly conditions for synthesizing polyaniline and polypyrrole [40].

Electrochemical Polymerization: This method allows direct deposition of conductive polymer films onto electrode surfaces, enabling precise control over film thickness and morphology [36] [40]. The process involves applying a potential to oxidize monomers in solution, forming polymer films on the working electrode [40]. This technique is particularly valuable for creating neural interfaces and biosensors.

Interfacial Polymerization: This approach creates polymers at liquid-liquid or liquid-solid interfaces, resulting in materials with high porosity and specific surface area [40]. For example, PEDOT produced through interfacial polymerization can achieve a porosity of 70.61% and specific surface area >58 m²/g, making it ideal for supercapacitors and sensing applications [40].

Advanced Processing and Patterning Techniques

For integration into bioelectronic devices, conductive polymers require precise patterning and deposition:

Solution-Based Processing: Techniques including spin coating, drop coating, shear coating, and dip coating enable simple deposition of conductive polymer thin films [41]. These methods benefit from the processability of many conductive polymers and their composites.

Printing Technologies: Inkjet printing, screen printing, and 3D printing allow patterned deposition of conductive polymers for flexible electronics [41]. These additive manufacturing approaches enable complex geometries and customized device architectures.

Laser Processing: Recent advances demonstrate high-fidelity patterning of PEDOT:PSS films using laser systems, creating customized sensor arrays for wearable and implantable applications [39].

Experimental Protocol: In Situ Polymerization of PEDOT:PSS Nanocomposites

Objective: To create a highly conductive PEDOT:PSS film with vertical phase separation for bioelectronic applications.

Materials:

- Commercial PEDOT:PSS ink

- Ethylene glycol (EG)

- Metastable liquid-liquid contact (MLLC) doping dispersion

- Polyurethane substrate

- Blade coater

- Annealing oven

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Clean and treat polyurethane substrate with oxygen plasma to ensure uniform wettability.

- Prismatic Film Formation: Blade coat commercial PEDOT:PSS ink onto substrate at controlled thickness (typically 1-5 µm) and drying conditions.

- Solid-Liquid Interface Doping: Shear MLLC-doping dispersion onto the pristine film surface. The MLLC dispersion is an EG-diluted PEDOT:PSS formulation with reduced PSS/PEDOT molar ratio (~1.73).

- Phase Separation Induction: During annealing at 60-80°C, solvent evaporation prompts hydrophilic PSS chains to accumulate at the surface while PEDOT-rich domains form high crystallization at the bottom.

- Characterization: Verify vertical phase separation through XPS depth profiling, with PSS/PEDOT ratio decreasing from 11.5 at the surface to 0.74 at the bottom [39].

Key Parameters: Coating speed, doping solvent composition, and annealing conditions critically influence the resulting vertical phase separation and conductivity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Conductive Polymer Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS | Primary conductive polymer for flexible electronics | Aqueous dispersion, tunable conductivity, transparency, commercial availability [41] [39] |

| Polyaniline (PANI) | Versatile conductive polymer for sensors and energy storage | Three oxidation states, pH-dependent conductivity, environmental stability [36] [41] |

| Polypyrrole (PPy) | Biocompatible polymer for neural interfaces and biosensors | Good environmental stability, redox properties, ease of polymerization [36] [41] |

| Ethylene Glycol (EG) | Secondary dopant for PEDOT:PSS | Enhances conductivity by inducing phase separation and improving PEDOT crystallinity [39] |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Common secondary dopant for conductive polymers | Improves charge transport properties by modifying polymer chain arrangement [39] |

| Carbon Nanotubes | Conductive fillers for nanocomposites | High aspect ratio, exceptional conductivity, mechanical reinforcement [36] [37] |

| Graphene and Derivatives | Two-dimensional conductive fillers | High surface area, excellent electrical and thermal properties [36] [37] |

| Biodegradable Polymer Matrices | Substrates for bioresorbable electronics | PLA, PCL, gelatin; provide temporary support then degrade [43] [37] |

Bioelectronic Applications and Experimental Outcomes

Neural Interfaces and Recording Systems

Conductive polymers have revolutionized neural interface technology by providing softer, more compliant electrode materials. Standard parameters for neural electrodes include low impedance, high charge storage capacity, and appropriate charge injection limits [38]. CP-based electrodes significantly improve these parameters: