Wearable Biosensors for Continuous Health Monitoring: Technologies, Applications, and Future Trends in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of wearable biosensors for continuous health monitoring, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Wearable Biosensors for Continuous Health Monitoring: Technologies, Applications, and Future Trends in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of wearable biosensors for continuous health monitoring, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles and evolution of biosensing technologies, from early electrocardiogram monitors to modern microneedle arrays and sweat-based platforms. The review delves into methodological advances in electrochemical, optical, and piezoelectric sensing modalities and their specific applications in therapeutic drug monitoring, chronic disease management, and vital sign tracking. The article critically examines persistent technological challenges, including selectivity, stability, and biofouling, while presenting validation frameworks and comparative performance analyses across sensing modalities. By synthesizing current research and market trends, this work aims to inform the development of next-generation biosensors and their integration into personalized medicine and decentralized clinical trials.

The Evolution and Core Principles of Wearable Biosensing Technology

The evolution from the bulky, intrusive biomonitoring systems of the Apollo era to today's seamless epidermal electronics represents a profound transformation in healthcare monitoring. This trajectory mirrors advancements in material science, microelectronics, and a deepening understanding of human physiology. The foundational work conducted by NASA during the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs established the critical need for continuous physiological monitoring in extreme environments [1]. These early systems, while revolutionary for their time, posed significant challenges in terms of astronaut comfort and signal reliability. Today, the field of epidermal electronics is overcoming these historical limitations through devices characterized by exceptional softness, breathability, and mechanoelectrical stability, enabling high-fidelity, long-term health monitoring that seamlessly integrates with the human body [2]. This application note details the key technological milestones along this journey and provides structured experimental protocols for modern epidermal electronic systems, contextualized within ongoing research for continuous health monitoring.

Historical Progression & Quantitative Analysis

The biomedical monitoring systems developed for NASA's early spaceflight programs were driven by a fundamental need to understand the human body's response to the novel environment of space. Key concerns included cardiovascular function in weightlessness, fluid distribution, and physiological adaptations upon return to Earth [1]. The initial solutions, though functional, were characterized by a mechanical and intrusive approach.

Apollo-Era Biomonitoring Systems:

- Electrocardiogram (ECG): Monitored via electrodes with orange wires connected to signal conditioners designed to reject noise from movement and vibration [1].

- Respiration: Initially tracked via a heated thermistor placed in front of the mouth, which was later replaced by an impedance pneumograph technique that measured changes in chest tissue impedance during breathing [1].

- Temperature: Measured using a rectal probe for high accuracy, later replaced with an oral sensor for Gemini and Apollo missions due to astronaut discomfort [1].

- Blood Pressure: Assessed using a semiautomatic sphygmomanometer with a pressure cuff and microphone [1].

The transition to modern epidermal electronics has been enabled by a paradigm shift in design philosophy and material innovation, focusing on conformability, biocompatibility, and non-invasiveness.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Biomonitoring Technologies Across Eras

| Monitoring Parameter | Apollo-Era Technology & Characteristics | Modern Epidermal Electronic Technology & Characteristics | Key Performance Advancements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrophysiological Signals (ECG, EMG, EEG) | Electrodes with wired connections to external signal conditioners; prone to motion artifacts [1]. | Soft, self-adhesive electrodes using materials like Au nanomesh or AgNW; serpentine structures for stretchability (up to 40-50%) [2] [3]. | High signal-to-noise ratio; seamless, long-term monitoring; resistance variation <1.2% after 50,000 bending cycles [2]. |

| Respiration | Impedance pneumography with electrodes placed near the 6th rib [1]. | Thin-film, breathable sensors capable of detecting chest wall movement via capacitive or impedance methods [2]. | Improved comfort for long-term use; high-fidelity data without skin irritation. |

| Temperature | Rectal probe (Mercury); Teflon-coated oral probe (Apollo) [1]. | Ultra-thin, skin-conformable thermistors based on piezoresistive/thermoresistive principles [2]. | Non-invasive, continuous monitoring; minimal discomfort. |

| Biochemical Sensing (e.g., Lactate, Glucose) | Largely unavailable during Apollo missions. | Electric Double Layer (EDL)-based biosensors and graphene-based electrochemical sensors analyzing sweat or interstitial fluid [4] [3]. | Real-time, non-invasive tracking of biomarkers; high sensitivity and selectivity enabled by nanomaterials [4]. |

| Mechanical Integrity | Rigid or flexible substrates with mechanical mismatch to skin. | Structures such as serpentine, kirigami, and 3D helical designs; use of liquid metals (e.g., Galinstan) [2] [3]. | Excellent stretchability (>30%), comfort, and mechanoelectrical stability for long-term use [2]. |

Table 2: Core Material Properties in Modern Epidermal Electronics

| Material Category | Example Materials | Key Properties | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metallic Materials | Gold (Au), Silver Nanowires (AgNW), Galinstan [3] | High electrical conductivity (e.g., AgNW: 10^4–8×10^5 S/m), stretchability through structural design [2] [3]. | Conductors, electrodes, and sensing elements. |

| Polymeric Substrates | Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), Polyimide, Polyurethane (PU) [3] | High flexibility, biocompatibility, tunable mechanical strength (e.g., PDMS: 1-5 MPa) [3]. | Flexible substrate and encapsulation. |

| Conductive Polymers | PEDOT, Polypyrrole, Polyaniline [3] | Moderate conductivity (e.g., PEDOT: 300-1000 S/m), good mechanical properties [3]. | Electrodes, hole transport layers, biosensors. |

| Nanomaterials | Graphene, Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) [4] | High surface area, excellent electrical and mechanical properties, biocompatibility [4]. | Enhancing sensitivity and selectivity in biosensors. |

| Biomaterials | Chitosan, Hyaluronic Acid, Collagen [3] | Biocompatibility, biodegradability, low conductivity (e.g., Chitosan: 10^-5–10^-4 S/m) [3]. | Bio-interfaces, hydrogels for sweat analysis. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication of a Stretchable Nanomesh Epidermal Electrode

This protocol outlines the fabrication of highly soft, conformal-contact nanomesh electrodes for electrophysiological monitoring (e.g., ECG, EMG) [2].

1. Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Nanomesh Electrode Fabrication

| Item Name | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Electrospinning Apparatus | A system including a high-voltage power supply, syringe pump, and grounded collector for producing polymer nanofibers. |

| Polymer Solution (e.g., Polyamide, PVA) | Serves as the sacrificial or structural template for the conductive nanomesh. |

| Silver Nanowire (AgNW) Dispersion | Forms the conductive network of the nanomesh. AgNWs provide high conductivity and mechanical flexibility. |

| Electrospray Attachment | Used to simultaneously deposit the AgNW dispersion onto the electrospun nanofibers. |

| Etching Solution (e.g., Water) | Selectively removes the sacrificial polymer fiber template if required, leaving a freestanding AgNW nanomesh. |

2. Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a homogeneous polymer solution (e.g., 10% w/v Polyamide in formic acid) and a well-dispersed AgNW suspension in a suitable solvent (e.g., ethanol).

- Simultaneous Electrospinning/Electrospraying: Mount the polymer syringe and the AgNW dispersion syringe on the apparatus. Simultaneously initiate electrospinning of the polymer and electrospraying of the AgNWs onto a rotating drum collector.

- Critical Parameters: Applied voltage (10-20 kV), flow rate (0.5-2 mL/h), tip-to-collector distance (10-20 cm), and ambient temperature/humidity [2].

- Transfer to Substrate: The resulting hybrid nanomesh mat, with AgNWs coated on the polymer fibers, can be directly transferred onto a temporary tattoo paper or a stretchable substrate like PDMS.

- Template Removal (Optional): If a pure metallic nanomesh is desired, immerse the structure in a solvent that dissolves the sacrificial polymer template (e.g., water for PVA), leaving a freestanding AgNW network.

- Characterization: Validate the electrical conductivity (e.g., sheet resistance ~4.14 Ω sq⁻¹) and mechanical properties (e.g., stretchability up to 50%) [2].

Diagram 1: Nanomesh electrode fabrication workflow.

Protocol: Functionalization of a Graphene-Based Sweat Biosensor

This protocol describes the modification of a graphene-based electrochemical sensor for continuous, non-invasive monitoring of biomarkers (e.g., glucose, lactate) in sweat [4] [5].

1. Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 4: Essential Materials for Graphene-Based Sweat Biosensor

| Item Name | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Graphene Electrode | The transduction element; high surface area and excellent electrical conductivity form the sensor's foundation. |

| Specific Enzyme (e.g., Glucose Oxidase for Glucose Sensing) | The biorecognition element that selectively catalyzes a reaction with the target biomarker. |

| Cross-linking Agent (e.g., Glutaraldehyde) | Forms stable covalent bonds to immobilize the enzyme onto the graphene surface. |

| Nafion Solution | A permeslective membrane coating that reduces interference from other electroactive species in sweat (e.g., ascorbic acid, uric acid). |

| Chitosan | A biocompatible polymer often used as a matrix to entrap and stabilize enzymes on the electrode surface. |

2. Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Electrode Pretreatment: Clean the graphene working electrode sequentially with ethanol and deionized water, then perform electrochemical activation (e.g., via cyclic voltammetry in a suitable buffer) to introduce functional groups.

- Enzyme Immobilization: Prepare an immobilization cocktail containing the specific enzyme (e.g., 10 mg/mL Glucose Oxidase), a cross-linker (e.g., 2.5% glutaraldehyde), and a matrix polymer (e.g., 1% chitosan). Deposit a precise volume (e.g., 5 µL) onto the graphene electrode and allow it to cross-link at room temperature.

- Membrane Coating: To enhance selectivity, coat the modified electrode with a thin layer of Nafion (e.g., 1 µL of 0.5% solution) and allow it to dry.

- Calibration and Validation: Calibrate the sensor in artificial sweat or buffer solutions with known concentrations of the target analyte using amperometry (e.g., at +0.5V vs. Ag/AgCl). Correlate the measured current output with analyte concentration.

Diagram 2: Biosensor functionalization and calibration process.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 5: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Epidermal Electronics

| Item Name | Function/Explanation | Representative Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Silver Nanowires (AgNWs) | Provide a conductive, transparent, and flexible network for electrodes and interconnects [2] [3]. | Fabrication of stretchable nanomesh electrodes for ECG monitoring [2]. |

| Liquid Metal (Galinstan) | Offers exceptional stretchability and self-healing properties for circuits on soft substrates [3]. | Creating ultra-stretchable wires and sensors that can withstand extreme deformation. |

| Conductive Polymer (PEDOT:PSS) | A biocompatible, flexible polymer with mixed ionic-electronic conductivity, ideal for interfacing with biological tissues [3]. | Used as a coating for electrodes to improve signal quality in electrophysiology. |

| Graphene Inks | Enable printing of high-performance, flexible sensing components with excellent electrical properties [4]. | Screen-printing electrodes for electrochemical detection of biomarkers in sweat. |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | A silicone elastomer used as a soft, flexible, and transparent encapsulant or substrate [3]. | Encapsulating fragile electronic components to create a robust, skin-worn patch. |

| Electrospinning Polymer (PVA, Polyamide) | Used to create fibrous templates (sacrificial or structural) for forming breathable, porous electronic membranes [2]. | Forming the scaffold for a breathable nanomesh electrode. |

| Chitosan | A biocompatible and biodegradable polysaccharide used as a hydrogel matrix for enzyme immobilization [3] [5]. | Entrapping glucose oxidase on the surface of a sweat sensor to enhance stability. |

| Nafion Solution | A permeslective membrane that minimizes fouling and interference from undesired anions in complex biofluids [5]. | Coating a lactate biosensor to improve selectivity in sweat analysis. |

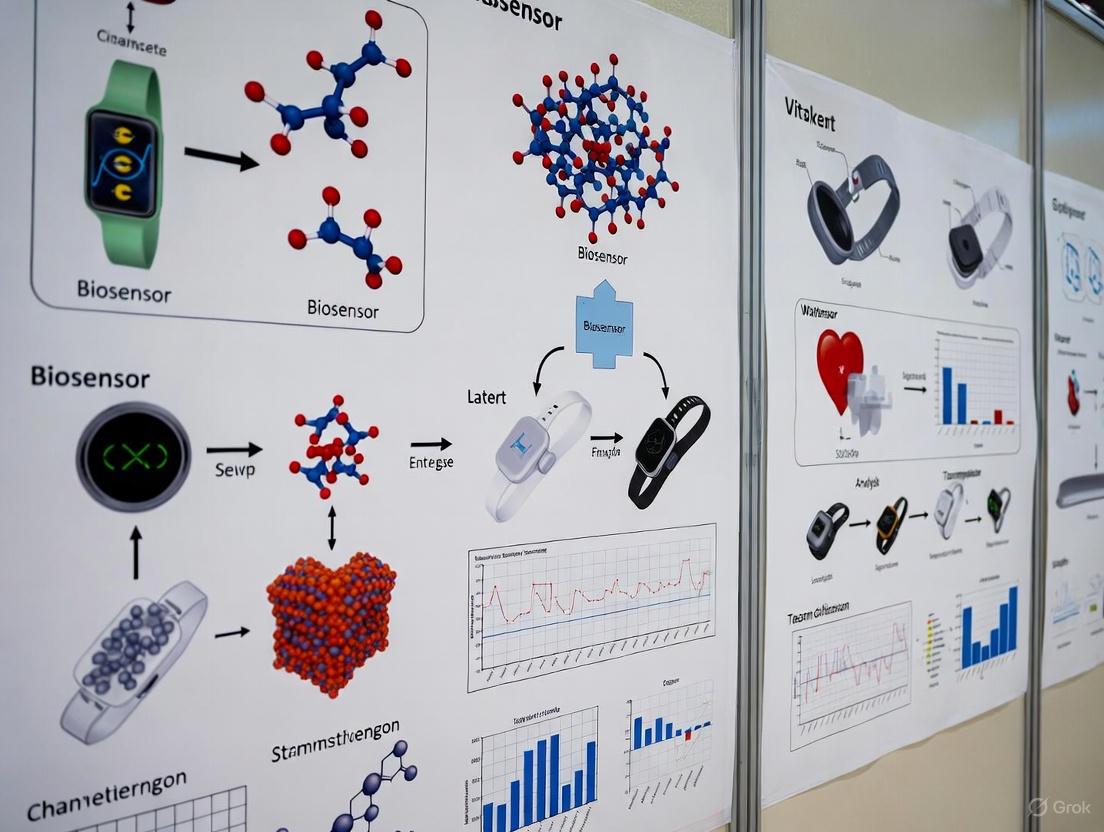

Biosensors are powerful analytical devices that combine a biological recognition element with a transducer to detect specific analytes, enabling rapid and sensitive diagnostics. Originally pioneered over 55 years ago with the development of the glucose oxidase electrode, biosensor technology has since expanded dramatically, finding critical applications in healthcare, environmental monitoring, and food safety [6]. In the context of wearable technologies for continuous health monitoring, understanding the fundamental architecture of biosensors is paramount for developing devices capable of non-invasive, real-time tracking of physiological biomarkers [7] [4]. This document outlines the core components, operational principles, and practical methodologies central to biosensor design and implementation, with particular emphasis on applications in continuous health monitoring research.

Core Components of a Biosensor

All biosensors consist of three fundamental components that work in concert to detect and quantify a target analyte: a biorecognition element for specific sequestration, a transducer for converting the biological event into a measurable signal, and a signal processor for interpreting the output [6] [8]. The synergistic operation of these components enables the translation of a biochemical binding event into quantifiable analytical data.

Biorecognition Elements

The biorecognition element provides the specificity critical for targeted analyte detection. These elements can be biologically derived or synthetically engineered, each with distinct characteristics influencing overall biosensor performance in terms of sensitivity, selectivity, reproducibility, and reusability [6].

Table 1: Comparison of Common Biorecognition Elements

| Biorecognition Element | Type | Binding Mechanism | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody [6] | Natural (Affinity-based) | Forms a 3D immunocomplex with antigen | High specificity and accuracy | Costly production; limited stability |

| Enzyme [6] | Natural (Catalytic) | Catalytic conversion of analyte | High sensitivity; amplifies signal | Stability dependent on environment |

| Aptamer [6] | Pseudo-natural (Affinity-based) | Folding into 3D structure for target binding | High stability; tunable for various targets | SELEX discovery process is costly |

| Nucleic Acid (DNA) [6] | Natural (Affinity-based) | Complementary base-pairing | High predictability and specificity | Limited to nucleic acid targets |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) [6] | Synthetic (Affinity-based) | Size, shape, and functional group complementarity | High stability and low cost | Can suffer from heterogeneity |

Transducers

The transducer is the component that converts the biological recognition event into a quantifiable electrical or optical signal. The choice of transducer defines the primary classification of the biosensor and is crucial for determining sensitivity and applicability [8].

- Electrochemical Transducers: These are among the most common, particularly in point-of-care and wearable devices. They measure electrical changes—such as current (amperometric), potential (potentiometric), or impedance (impedimetric)—resulting from the biorecognition event. They are prized for their high sensitivity, low cost, and ease of miniaturization [8]. For example, the catalytic action of an enzyme like glucose oxidase generates a measurable current proportional to glucose concentration [6].

- Optical Transducers: These transducers detect changes in light properties, including absorbance, fluorescence, or refractive index (as in surface plasmon resonance). They offer high accuracy and are resistant to electromagnetic interference, making them suitable for complex biological matrices [8].

- Piezoelectric Transducers: These devices measure changes in mass or mechanical resonance upon binding of the target analyte. They are valuable as reliable diagnostic tools but can be less suited for miniaturized, wearable form factors [8].

Signal Processing

The signal processor, or reader device, acquires the raw signal from the transducer and converts it into user-interpretable data. This involves signal amplification, filtering, and quantification [8]. Advanced signal processing often employs techniques like differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) or electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) for electrochemical sensors [8]. The limit of detection (LOD) is a key metric calculated as LOD = 3σ/S, where σ is the standard deviation of the blank signal and S is the sensitivity of the sensor [8]. Integration with machine learning (ML) algorithms is an emerging trend that enhances data analysis, enables anomaly detection, and improves sensor performance by filtering out interference [8].

Biosensor Architecture and Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow and logical relationships between the core components of a typical biosensor system.

Application in Wearable Biosensors

The fundamental biosensor architecture is the foundation for the development of advanced wearable devices for continuous, non-invasive health monitoring. These devices leverage breakthroughs in material science and microfluidics to interface with the human body.

- Sampling Bodily Fluids: Wearable biosensors often analyze easily accessible biofluids like sweat, tears, or saliva, which contain a rich profile of physiological biomarkers [7] [9]. For instance, sweat-based wearable biosensors represent a new era for tracking metabolites and electrolytes [7], while tear-based sensors can monitor intraocular pressure and glucose levels [9].

- Integration of Nanomaterials: The use of nanomaterials, particularly graphene, has dramatically enhanced wearable biosensor performance. Graphene provides exemplary electrical properties, mechanical flexibility, and a tunable surface chemistry that allows for the effective immobilization of various biorecognition elements [4]. This is critical for creating durable, sensitive, and flexible sensing platforms.

- System Architecture: A typical wearable device integrates a flexible substrate holding the biosensor, which is often coupled with microfluidic channels for controlled fluid management (e.g., sweat sampling). The system includes the necessary electronics for signal transduction and processing, and increasingly features wireless connectivity for real-time data transmission to a smartphone or cloud-based platform [4].

Experimental Protocols

This section provides a detailed methodology for fabricating and characterizing a model electrochemical biosensor, a common platform for wearable health monitoring applications.

Protocol: Fabrication of a Graphene-Based Electrochemical Biosensor

Objective: To immobilize a biorecognition element (e.g., an enzyme or aptamer) on a graphene-based transducer and characterize its electrochemical performance [4] [8].

Materials:

- Graphene-modified screen-printed electrode (or a flexible graphene electrode)

- Biorecognition element solution (e.g., 1 mg/mL glucose oxidase in phosphate buffer)

- Coupling agents: EDC (1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide) and NHS (N-Hydroxy succinimide)

- Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Washing buffer (e.g., PBS with 0.05% Tween 20)

- Electrochemical probe solution (e.g., 5 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ in PBS)

- Potentiostat

Procedure:

Electrode Pretreatment:

- Clean the graphene working electrode by performing 10 cycles of Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4) from -0.2 V to +0.6 V (vs. Ag/AgCl reference) at a scan rate of 50 mV/s.

- Rinse the electrode thoroughly with deionized water and dry under a gentle stream of nitrogen gas.

Surface Functionalization:

- Prepare a fresh solution of 2 mM EDC and 5 mM NHS in deionized water.

- Deposit 10 µL of the EDC/NHS mixture onto the active surface of the graphene working electrode.

- Incubate for 1 hour at room temperature in a humid chamber to prevent evaporation.

- Rise the electrode gently with PBS to remove unreacted EDC/NHS.

Biorecognition Element Immobilization:

- Apply 10 µL of the biorecognition element solution (e.g., glucose oxidase) to the activated electrode surface.

- Incubate for 2 hours at 4°C in a humid chamber.

- After incubation, rinse the electrode with washing buffer to remove physically adsorbed molecules.

Blocking:

- To minimize non-specific binding, treat the electrode with 10 µL of 1% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) solution for 30 minutes.

- Rinse again with PBS and store in PBS at 4°C until use.

Protocol: Performance Characterization via Electrochemical Measurements

Objective: To evaluate the sensitivity, selectivity, and limit of detection (LOD) of the fabricated biosensor.

Procedure:

Electrochemical Characterization:

- Immerse the fabricated biosensor in a stirred electrochemical probe solution ([Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻).

- Record the CV from -0.2 V to +0.6 V at a scan rate of 50 mV/s. A successful immobilization is indicated by a decrease in the Faradaic current due to the insulating layer of biomolecules on the electrode surface.

- Perform Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) in the same solution, applying a frequency range from 0.1 Hz to 100 kHz at a formal potential. Use the resulting Nyquist plot to quantify the electron transfer resistance (Rₑₜ).

Calibration and LOD Calculation:

- Prepare a series of standard solutions with known concentrations of the target analyte.

- Measure the amperometric response (e.g., at a constant potential of +0.5 V) of the biosensor upon successive additions of the standard solutions.

- Plot the steady-state current response against the analyte concentration to generate a calibration curve.

- Calculate the sensitivity (S) from the slope of the linear region of the calibration curve.

- The LOD is calculated using the formula: LOD = 3σ/S, where σ is the standard deviation of the blank signal (response in the absence of analyte) measured across multiple sensors (n≥3) [8].

The following diagram illustrates the specific mechanism of an enzymatic electrochemical biosensor, a foundational concept for many continuous monitoring devices.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Biosensor Development

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Graphene Nanostructures [4] | Transducer material providing high electrical conductivity, flexibility, and large surface area for biomolecule immobilization. | Synthesized via chemical vapor deposition or from graphene oxide; ideal for wearable form factors. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) [8] | Nanomaterial for electrode modification; increases active surface area, enhancing signal and sensitivity. | Used in 3D nano/microislands (NMIs); compatible with thiol-based chemistry for biomolecule attachment. |

| EDC & NHS Crosslinkers [8] | Activate carboxyl groups on sensor surfaces to form stable amide bonds with amine-containing biomolecules (e.g., antibodies, aptamers). | Standard protocol for covalent immobilization; critical for stable and oriented surface attachment. |

| Thiol-Modified Aptamers [8] | Biorecognition elements immobilized on gold surfaces via strong Au-S bonds. | Provide high stability and selectivity; can be engineered via SELEX for various targets. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) [6] | Synthetic biorecognition elements with templated cavities for target analyte. | Offer an alternative to biological receptors with superior stability and lower cost. |

| Polypyrrole Films [8] | Conducting polymer formed via electropolymerization; used to entrap enzymes and other biomolecules on electrode surfaces. | Provides a versatile and controllable matrix for biomolecule immobilization. |

The advancement of wearable biosensors is revolutionizing continuous health monitoring by providing real-time, non-invasive physiological data [10] [5]. For researchers and drug development professionals, the translation of a biosensing concept into a reliable diagnostic tool hinges on the rigorous characterization of its core analytical performance metrics [8]. These metrics—sensitivity, selectivity, limit of detection (LOD), and dynamic range—serve as the fundamental benchmarks that validate a sensor's capability to accurately and reliably quantify biomarkers in complex biological fluids like sweat, saliva, and interstitial fluid [11] [12].

Establishing these parameters is crucial for ensuring that data generated for clinical diagnostics, chronic disease management, such as diabetes, and fitness tracking meets the stringent requirements for regulatory approval and clinical acceptance [13] [11]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for the precise determination of these critical metrics within the context of wearable biosensor development.

Core Metric Definitions and Quantitative Benchmarks

The table below defines the four core analytical metrics and presents quantitative examples from recent literature to illustrate their application in evaluating wearable biosensor performance.

Table 1: Core Analytical Performance Metrics and Representative Data from Wearable Biosensor Research

| Metric | Definition | Significance in Wearable Biosensors | Exemplary Performance from Recent Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | The magnitude of signal change per unit change in analyte concentration [14]. | High sensitivity enables detection of low-abundance biomarkers crucial for early disease diagnosis [15]. | A glucose sensor achieved a sensitivity of 95.12 ± 2.54 µA mM⁻¹ cm⁻² [14]. |

| Selectivity | The sensor's ability to respond exclusively to the target analyte in the presence of interferents [8]. | Critical for accurate operation in complex biofluids (e.g., sweat, saliva) containing multiple chemical species [11]. | Specificity is conferred by the biorecognition element (e.g., enzyme, antibody, aptamer) [11] [8]. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | The lowest analyte concentration that can be reliably distinguished from a blank sample [8]. | Determines the utility for detecting biomarkers at their physiologically relevant low concentrations [15]. | A SERS-based miRNA sensor reported an LOD of 3.46 aM [15]. Calculated as LOD = 3σ/S, where σ is the standard deviation of the blank and S is sensitivity [8]. |

| Dynamic Range | The span of analyte concentrations over which the sensor provides a quantifiable response [14]. | Must encompass the physiologically relevant concentration range of the target biomarker for clinical utility [12]. | A fluorescent biosensor for a miRNA biomarker exhibited a dynamic range of 0.1–10 pM [15]. |

Experimental Protocols for Metric Validation

Protocol for Calibration Curve, Sensitivity, and LOD Determination

This protocol outlines the procedure for establishing a sensor's calibration curve, from which its sensitivity and Limit of Detection are derived.

1. Principle: A biosensor's response (e.g., current, voltage, fluorescence intensity) is measured across a series of standard solutions with known analyte concentrations. A calibration curve is constructed by plotting the signal against concentration, and its parameters are used to calculate sensitivity and LOD [14] [8].

2. Research Reagent Solutions: Table 2: Essential Reagents for Sensor Calibration and Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Target Analyte Standard | High-purity reference material for preparing calibration solutions with known concentrations. |

| Buffer Solution (e.g., PBS) | Provides a stable ionic strength and pH background that mimics the intended biofluid. |

| Electrochemical Cell / Optical Cuvette | The container for the sample and sensor during measurement, ensuring consistent geometry. |

| Potentiostat / Spectrometer | Instrumentation to apply the excitation (electrical potential, light) and measure the resulting signal. |

3. Procedure:

- Preparation of Standard Solutions: Prepare a dilution series of the target analyte in an appropriate buffer (e.g., PBS, synthetic sweat). The concentration range should be designed to bracket the expected physiological and pathological levels.

- Sensor Measurement: For each standard solution, introduce the sensor and record the steady-state output signal. For electrochemical sensors, techniques such as Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) or Amperometry are commonly used [8]. For optical sensors, measure fluorescence intensity or absorbance.

- Data Analysis:

- Calibration Curve: Plot the measured signal (y-axis) against the analyte concentration (x-axis). Perform linear regression to obtain the equation of the best-fit line (y = mx + c), where

mis the slope. - Sensitivity Calculation: The slope of the calibration curve (

m) is the analytical sensitivity of the sensor [14]. - LOD Calculation: Measure the standard deviation (σ) of the signal from at least ten blank (analyte-free) solutions. Calculate the LOD using the formula: LOD = 3σ / m, where

mis the sensitivity from the calibration curve [8].

- Calibration Curve: Plot the measured signal (y-axis) against the analyte concentration (x-axis). Perform linear regression to obtain the equation of the best-fit line (y = mx + c), where

Protocol for Selectivity and Specificity Assessment

This protocol validates that the sensor's signal is generated primarily by the target analyte, even in the presence of structurally similar compounds or common biofluid constituents.

1. Principle: The sensor's response to the target analyte is compared to its response to potential interfering substances at physiologically relevant concentrations. A highly selective sensor will show a significantly stronger response to the target [8].

2. Research Reagent Solutions:

- Potential Interferents: Substances commonly found in the target biofluid (e.g., glucose for lactate sensors, ascorbic acid, uric acid, urea, common salts).

- Biorecognition Element: The key to selectivity (e.g., glucose oxidase, specific antibody, DNA aptamer) [11] [8].

3. Procedure:

- Identify Interferents: Compile a list of potential interfering species based on the composition of the target biofluid (e.g., sweat, ISF) and the sensor's operating principle.

- Prepare Solutions: Prepare separate solutions containing the target analyte at a fixed concentration (e.g., at the middle of its dynamic range) and solutions containing each potential interferent at a concentration at or above its maximum expected physiological level.

- Measure Response: Measure the sensor's signal for the target analyte solution and for each interferent solution.

- Calculate Selectivity Coefficient: The relative response is calculated as (SignalInterferent / SignalTarget) × 100%. A low percentage indicates high selectivity. A more formal parameter is the Selectivity Coefficient (k), where a value << 1 indicates high selectivity for the target over the interferent.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The reliability of a wearable biosensor is fundamentally linked to the quality and properties of the materials and reagents used in its construction and operation. The following table details essential components.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Wearable Biosensor Development

| Category / Item | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Biorecognition Elements | |

| Enzymes (e.g., Glucose Oxidase) | Catalyze a specific reaction with the target analyte, producing a measurable product (e.g., H₂O₂) [8]. |

| Antibodies & Aptamers | Provide high-affinity binding for specific bioaffinity sensing (immunosensors, aptasensors), crucial for detecting proteins, hormones, or pathogens [8] [15]. |

| Nanomaterials | |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) & Graphene | Enhance electrochemical signal transduction and provide a high-surface-area platform for immobilizing biorecognition elements, directly improving sensitivity [8] [5]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Promote electron transfer in electrochemical sensors and can be used as transducing materials [15]. |

| Sensor Platform & Fabrication | |

| Flexible Polymers (e.g., PDMS) | Provide stretchable, skin-conformable substrates that are essential for wearable comfort and robust signal acquisition during movement [10] [5]. |

| Conductive Inks (e.g., Ag/CNT) | Enable printing of lightweight, flexible electrodes and circuits on various substrates, facilitating mass production [5]. |

| Hydrogels | Act as a biocompatible interface for sweat sampling and transport, mediating between the skin and the sensor [5]. |

| Data Acquisition & Validation | |

| Potentiostat/Galvanostat | Core instrument for applying potential and measuring current in electrochemical biosensors [8]. |

| Synthetic Biofluid (e.g., Artificial Sweat) | Provides a consistent and standardized medium for initial sensor characterization and validation [12]. |

The advancement of wearable biosensors for continuous health monitoring has intensified the focus on biofluids that can be sampled minimally or non-invasively. While blood remains the clinical gold standard for biomarker analysis, its collection is invasive and intermittent. Consequently, research has shifted towards alternative biofluids—sweat, interstitial fluid (ISF), and tears—which offer complementary advantages for decentralized, real-time monitoring. This Application Note provides a comparative analysis of these key biofluids, detailing their composition, biomarker relevance, and associated sampling protocols to inform the development of next-generation wearable biosensing platforms.

Comparative Biofluid Analysis

The selection of an appropriate biofluid is contingent upon the target biomarker's concentration, correlation with systemic levels, and the feasibility of sampling. The table below summarizes the characteristic concentrations of key biomarkers across these biofluids, informing sensor design and development.

Table 1: Characteristic Biomarker Concentrations in Key Biofluids

| Biomarker | Blood | Interstitial Fluid (ISF) | Sweat | Tears | Key Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium (Na⁺) | 136-146 mM [16] | ~135.7 mM [16] | 10-100 mM [17] | ~142 mM [17] | Electrolyte balance, hydration status [17] |

| Potassium (K⁺) | 3.5-5.0 mM [16] | ~4.0 mM [16] | 1-10 mM [17] | ~25 mM [17] | Electrolyte balance, renal function [17] |

| Glucose | 4.4-6.6 mM (fasting) | Highly correlated with blood [16] | 0.01-0.2 mM [17] | Correlated with blood [17] | Diabetes management [16] [17] |

| Lactate | 0.5-2.2 mM (venous) | Highly correlated with blood [16] | 5-25 mM (exercise) [17] | Information Missing | Metabolic stress, exercise physiology [16] |

| Cortisol | 80-500 nM (total) [16] | 5-50 nM [16] | Detectable [17] | Detectable [17] | Stress response, endocrine disorders [17] |

| Proteins (e.g., Albumin) | ~40 g/L (Albumin) | ~52% lower than blood [18] | >1000x lower than blood/ISF [16] | Rich in proteins (e.g., lysozyme) [17] | Inflammation, systemic disease [18] |

Table 2: Comparative Advantages and Challenges for Biosensing

| Biofluid | Key Advantages | Primary Challenges & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Blood | Gold standard; richest biomarker profile; strong clinical validation. | Invasive collection; requires expertise; clotting risk; not ideal for continuous wearables [17]. |

| Interstitial Fluid (ISF) | High correlation with blood for many biomarkers; no clotting; minimal dilution [18] [16]. | Requires minimally invasive sampling (e.g., microneedles); concentration gradients for large molecules [18] [16]. |

| Sweat | Easy, non-invasive access; relatively large volumes; diverse biomarkers [19] [17]. | Variable composition; dilution and contamination; correlation with blood can be complex [19] [17]. |

| Tears | Non-invasive; direct correlation for some biomarkers (e.g., glucose) [17]. | Very low volumes; low analyte concentrations; sensor stability in ocular environment [17]. |

Experimental Protocols for Biofluid Sampling and Analysis

Protocol: Microneedle-Based Sampling of Interstitial Fluid (ISF)

Principle: Hollow or solid microneedles breach the stratum corneum to access ISF in the dermis, enabling extraction or in-situ sensing with minimal pain [18] [16].

Materials:

- Microneedle Array: Solid, hollow, or hydrogel-forming microneedles.

- ISF Collection/Sensing Patch: Integrates microfluidic channels and electrodes.

- Functionalization Reagents: Enzymes (e.g., glucose oxidase) or Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) [20] [17].

- Adhesive Layer: Medical-grade adhesive for skin attachment.

- Readout System: Potentiostat or optical reader.

Procedure:

- Skin Site Preparation: Cleanse the application site (e.g., forearm, abdomen) with 70% ethanol and allow to dry.

- Microneedle Array Application: Apply the array using a custom applicator to ensure consistent penetration into the dermis.

- ISF Extraction/Sensing:

- Signal Transduction: Monitor electrochemical (amperometric/potentiometric) or optical signals continuously.

- Data Acquisition: Transmit data wirelessly (e.g., via Bluetooth) to a mobile device or cloud platform for real-time tracking [5].

Protocol: Continuous Monitoring in Sweat using a Microfluidic Patch

Principle: Eccrine sweat is collected autonomously via capillary microfluidics and analyzed in real-time using integrated electrochemical sensors [19] [17].

Materials:

- Microfluidic Patch: Hydrophilic polymer layer for capillary-driven flow.

- Electrochemical Sensors: Working, reference, and counter electrodes, often made from flexible carbon or graphene inks [5].

- Sweat Induction Module: Iontophoresis electrode (optional, for stimulation at rest).

- Hydrogel Interface: Ensures conformal contact with skin.

- Signal Processing Electronics: Miniaturized potentiostat and transmitter.

Procedure:

- Sensor Patch Integration: Assemble the microfluidic layer, hydrogel interface, and electrochemical sensors onto a flexible, adhesive substrate.

- Skin Attachment: Apply the patch securely to clean, dry skin (e.g., forearm, back).

- Sweat Induction (if required): Apply a mild electrical current via integrated iontophoresis electrodes to stimulate sweat generation [20].

- Autonomous Sampling: As sweat is produced, it is wicked via capillary forces through the microfluidic channels to the sensor chambers.

- In-situ Analysis: Electrochemical sensors (e.g., for lactate, glucose, ions) detect analytes. Colorimetric sensors can also be used for visual readout [17].

- Data Handling: Process and wirelessly transmit calibrated data for continuous monitoring.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The development of robust wearable biosensors relies on a specific toolkit of advanced materials and reagents.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Wearable Biosensor Development

| Item | Function & Utility | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Synthetic, stable antibody-like receptors for specific biomarker capture; ideal for continuous monitoring [20] [17]. | Detection of amino acids, vitamins, and cortisol in sweat and ISF [20]. |

| Plasmonic Nanoparticles (e.g., Gold Nanorods) | Enhance fluorescence signals >1000-fold; enable single-molecule detection in complex media like blood serum [21]. | Ultrasensitive DNA cancer marker detection via plasmon-enhanced fluorescence [21]. |

| Graphene & Carbon Nanotubes | Provide high electrical conductivity, flexibility, and large surface area; enhance sensor sensitivity and selectivity [4] [5]. | Working electrodes in electrochemical sensors for metabolites in sweat and ISF [20] [5]. |

| Hydrogels | Biocompatible, water-based polymers that interface between skin and sensor; facilitate analyte diffusion [5] [17]. | Medium for sweat collection and analyte transport to sensors in epidermal patches [5]. |

| Capillary Microfluidic Systems | Enable autonomous, pump-free transport of biofluids (e.g., sweat, ISF) using engineered wettability [17]. | Sequential routing of sweat to different sensing chambers for multi-analyte detection [17]. |

Wearable biosensors are fundamentally transforming modern healthcare by enabling continuous, non-invasive monitoring and real-time diagnostics across a myriad of medical applications [9]. These devices, which integrate biological elements, transducers, and electronic interfaces, represent a paradigm shift from episodic health assessment to continuous health insight, facilitating the emergence of personalized treatment strategies and Population Digital Health (PDH) [22]. The market for these technologies is experiencing significant growth, driven by rising demand for remote patient monitoring, decentralized clinical trials, and increasing consumer health awareness [13] [23]. This application note examines the market landscape and growth projections for wearable sensors through 2035, as forecasted by IDTechEx, while providing detailed experimental protocols for their evaluation in continuous health monitoring research.

Global Market Size and Growth Trajectory

IDTechEx forecasts that the wearable sensors market will reach US$7.2 billion by 2035, with a combined Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 5% for the period 2025-2035 [13]. This growth is embedded within the broader sensor market, which IDTechEx projects will grow to US$253 billion by 2035, demonstrating a conservative 6% CAGR [24]. This contextualizes wearable biosensors as a specialized, rapidly evolving segment within the larger sensing ecosystem, propelled by distinct technological and healthcare drivers.

Table 1: Wearable Sensors Market Forecast 2025-2035 (Key Segments)

| Sensor Technology Segment | Key Applications | Growth Drivers |

|---|---|---|

| Motion Sensors (Accelerometers, Gyroscopes) [13] | Health insurance rewards, clinical trials, professional athlete monitoring [13] | Commoditization pushing expanded application spaces [13] |

| Optical Sensors [13] | Heart-rate, blood oxygen, sleep quality; emerging: blood pressure, glucose [13] [23] | New PPG signal analysis software and spectroscopy hardware [13] |

| Wearable Electrodes (Wet, Dry, Microneedle) [13] | Vital sign monitoring, sleep analysis, emotional response, stress monitoring, brain-computer interfaces [13] [23] | Novel human-machine interfacing for AR and assistive technology [23] |

| Chemical Sensors [13] | Continuous Glucose Monitors (CGM), hydration analysis, lactate, alcohol monitoring [13] [23] | Expansion from type-1 to type-2 diabetes and mass consumer markets [23] |

Emerging Application Areas and Form Factors

The application landscape for wearable biosensors is diversifying beyond consumer wellness into mission-critical healthcare domains. A significant trend is the rise of Population Digital Health (PDH), which leverages digital health information from health Internet of Things (IoT) and wearable devices for population health modeling [22]. This approach contrasts with traditional methods reliant on electronic health records (EHRs) and health surveys, offering improved scale, coverage, equity, and cost-effectiveness for public health monitoring [22]. Concurrently, form factors are evolving from mainstream smartwatches and fitness trackers to include skin patches, smart clothing, hearables, and specialized medical devices, each creating unique opportunities for sensor integration and application-specific functionality [13].

Experimental Protocols for Wearable Biosensor Evaluation

Protocol: Validation of Optical Biosensor Performance for Physiological Monitoring

Objective: To quantitatively assess the accuracy and reliability of optical biosensors (e.g., photoplethysmography - PPG) in measuring heart rate and deriving cardiovascular parameters against certified medical-grade reference equipment.

Materials:

- Test Device: Wearable biosensor with optical sensing capabilities (e.g., smartwatch, PPG patch).

- Reference Device: FDA-cleared/CE-marked medical device (e.g., ECG holter monitor, clinical-grade pulse oximeter).

- Data Analysis Platform: Computer with software for statistical analysis (e.g., Python, R, MATLAB).

- Protocol Administration Setup: Controlled environment (e.g., clinical lab), treadmill or stationary bike for controlled physical stress.

Methodology:

- Participant Preparation: Recruit a cohort of participants representing varied demographics (age, sex, skin tone). Fit both the test and reference devices according to manufacturers' specifications.

- Data Collection Protocol: Conduct a multi-stage data collection session:

- Resting Phase (15 minutes): Participants sit comfortably without movement.

- Controlled Activity Phase (30 minutes): Participants engage in standardized activities on a treadmill or stationary bike at varying intensity levels (e.g., slow walk, brisk walk, run).

- Post-Exercise Recovery Phase (15 minutes): Participants return to a resting seated position.

- Data Synchronization and Processing: Precisely synchronize data timestamps from both devices. Extract concurrent data segments for all phases. For the test device, apply signal processing algorithms to filter motion artifacts and extract clean PPG waveforms and heart rate values.

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate the mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), and Pearson correlation coefficient (r) between the heart rate measurements from the test biosensor and the reference device. Bland-Altman analysis must be performed to assess the limits of agreement.

Protocol: Assessing Analytical Performance of Wearable Chemical Biosensors

Objective: To evaluate the sensitivity, specificity, and dynamic response of a wearable chemical biosensor (e.g., continuous glucose monitor CGM, sweat lactate sensor) against gold-standard laboratory analytical techniques.

Materials:

- Test Device: Wearable chemical biosensor (e.g., CGM, sweat sensor patch).

- Reference Method: Laboratory benchtop analyzer (e.g., YSI blood glucose analyzer, HPLC for lactate).

- Sample Collection Kit: For intermittent collection of reference samples (e.g., lancets for capillary blood, sweat stimulant).

- Calibration Standards: Certified reference materials for the target analyte.

Methodology:

- In-Vitro Calibration: Prior to in-vivo testing, perform a dose-response calibration by exposing the biosensor to a series of standard solutions with known analyte concentrations. Plot the sensor's output (e.g., electrical current, optical signal) against concentration to establish a calibration curve and determine the limit of detection (LOD) and linear range.

- In-Vivo Validation Study: Deploy the biosensor on participants according to the manufacturer's instructions. Throughout the wear period (e.g., 7-14 days for a CGM), collect paired reference samples at regular intervals. For interstitial fluid sensors, this involves finger-prick blood glucose measurements. For sweat sensors, this may involve collecting sweat via absorbent patches for subsequent laboratory analysis.

- Data Analysis and Performance Metrics: For each paired data point (sensor reading vs. reference value), calculate the relative absolute difference. Use the Clarke Error Grid analysis for glucose monitors to determine clinical accuracy. Calculate the Mean Absolute Relative Difference (MARD), which is a key industry metric for CGM performance.

Diagram 1: Chemical biosensor validation workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The development and validation of wearable biosensors require a suite of specialized reagents and materials to ensure analytical validity and clinical relevance.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Wearable Biosensor Development

| Research Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Biorecognition Elements [9] | Key component for selective target binding in biosensors. | Enzymes (Glucose Oxidase for CGM), Antibodies, Aptamers, Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs). |

| Nanomaterials [9] | Enhance sensor sensitivity and specificity via high surface area and novel properties. | Graphene, Carbon Nanotubes, Metal Nanoparticles, Quantum Dots. Used in transducers and electrodes. |

| Functional Inks [24] | Enable printing of flexible, stretchable sensor components. | Conductive (Silver Nanoparticle), Dielectric, Semiconductor inks for additive manufacturing. |

| Calibration Standards | Establish sensor accuracy and generate dose-response curves. | Certified Reference Materials for analytes (e.g., Glucose, Lactate, Cortisol) in buffer and synthetic biofluids. |

| Synthetic & Artificial Biofluids | Simulate the chemical matrix of real biological samples for controlled testing. | Artificial Sweat, Interstitial Fluid, Tears, and Saliva with controlled pH, ionic strength, and interferents. |

Signaling Pathways and Logical Frameworks for PDH

The implementation of Population Digital Health (PDH) relies on a logical framework for transforming raw sensor data into actionable population-level insights. This involves a multi-stage process that addresses key challenges such as data inadequacy, sensor inaccuracy, and spatiotemporal sparsity [22].

Diagram 2: Population digital health data flow.

The wearable biosensor market, projected to grow significantly to US$7.2 billion by 2035, represents a critical technological frontier for enabling continuous health monitoring and advancing biomedical research [13]. The successful implementation of these technologies in research and clinical practice hinges on rigorous, standardized experimental protocols for validation, as outlined in this document. Future research must focus on overcoming persistent challenges, including ensuring data accuracy across diverse populations and use contexts, establishing robust regulatory and quality standards tailored for personal health devices, and fostering effective public-private partnerships to enable the ethical and scalable use of data for Population Digital Health [22]. The integration of edge AI and machine learning for real-time signal processing and error compensation will be pivotal in enhancing the reliability and clinical adoption of the next generation of wearable biosensors [24].

Advanced Sensing Modalities and Their Transformative Biomedical Applications

Electrochemical biosensors represent a powerful class of analytical devices that integrate biological recognition elements with electrochemical transducers to convert target analyte information into measurable electrical signals [25]. These sensors have gained significant traction in clinical diagnostics and continuous health monitoring due to their exceptional sensitivity, portability, and capacity for real-time analysis [26]. The fundamental operating principle involves the specific interaction between an immobilized biorecognition element (such as an enzyme, antibody, or aptamer) and the target analyte, which generates an electrochemical signal (current, potential, conductance) proportional to the analyte concentration [25].

The emergence of non-invasive wearable biosensors marks a paradigm shift in metabolic monitoring, moving from single-point measurements to continuous physiological tracking [7]. Sweat, as a readily accessible biofluid, contains a rich repertoire of metabolites including glucose, lactate, urea, and electrolytes, providing a dynamic window into an individual's metabolic state [27]. Enzyme-based electrochemical biosensors specifically engineered for sweat analysis leverage the high specificity of biological recognition elements, enabling precise metabolite quantification without invasive blood sampling [7] [4]. This technological advancement is particularly transformative for managing conditions like diabetes and for optimizing athletic performance, where frequent metabolite monitoring is crucial [26].

Recent innovations in graphene-based technologies and microfluidic integration have dramatically enhanced the performance of wearable electrochemical biosensors [4]. Graphene's exemplary electrical properties, mechanical flexibility, and biocompatibility make it an ideal material for shaping the future of wearable sensing devices [4]. Furthermore, the integration of microfluidic approaches has improved sample handling and sensor performance, enabling more reliable metabolite tracking in complex biological fluids like sweat [4].

Key Metabolites and Analytical Performance

Electrochemical biosensors have been successfully developed for a range of clinically relevant metabolites present in sweat. The table below summarizes the analytical performance for key biomarkers.

Table 1: Analytical Performance of Electrochemical Biosensors for Key Metabolites

| Target Analyte | Biorecognition Element | Linear Detection Range | Detection Limit | Transduction Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | Glucose Oxidase (GOx) / Glucose Dehydrogenase (GDH) | 1 nM – 100 mM [26] | 0.12 nM [26] | Amperometric (H₂O₂ oxidation) |

| Lactate | Lactate Oxidase / Lactate-specific Aptamer | 0 – 30 mM [27] | 0.078 mM [27] | Fluorescence (FRET-based) / Amperometric |

| General Biomarkers | Various Enzymes/Antibodies | N/A | N/A | Potentiometric, Conductometric, Impedimetric |

The selection of an appropriate biorecognition element is critical for biosensor performance. Enzymes like glucose oxidase (GOx) offer high specificity but can be susceptible to oxygen interference [26]. Alternative enzymes such as pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ) or FAD-dependent glucose dehydrogenase (GDH-FAD) have been employed to overcome this limitation, as they do not require oxygen as an electron acceptor [26]. For lactate sensing, L-lactate-specific aptamers integrated with fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) systems achieve exceptional precision and ultralow detection limits, making them suitable for the low concentration ranges typically found in sweat [27].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Fabricating a Graphene-Based Glucose Biosensor

This protocol outlines the development of an amperometric glucose biosensor leveraging graphene nanomaterials to enhance sensitivity.

Materials and Reagents:

- Glucose Oxidase (GOx) from Aspergillus niger

- Graphene nanostructures (e.g., functional graphene sheets - FGS)

- Chitosan solution (1% w/v in dilute acetic acid)

- Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Glutaraldehyde (2.5% v/v solution for cross-linking)

- Platinum nanoparticle suspension

- Screen-printed carbon electrodes (SPCEs)

Procedure:

- Electrode Modification: Prepare a homogeneous nanocomposite by thoroughly mixing 1 mg of FGS with 1 mL of chitosan solution. Deposit 5 µL of this suspension onto the working electrode area of the SPCE and allow it to dry at room temperature.

- Platinum Decoration: To enhance electrocatalytic activity, add 3 µL of platinum nanoparticle suspension onto the FGS/chitosan-modified electrode. Dry under inert atmosphere.

- Enzyme Immobilization: Prepare the enzyme solution by dissolving 5 mg of GOx in 1 mL of PBS. Apply 5 µL of this solution to the modified electrode surface.

- Cross-linking: To stabilize the enzyme layer, expose the electrode to glutaraldehyde vapor for 30 minutes at 4°C. This step creates covalent bonds that securely immobilize the enzyme.

- Biosensor Storage: Store the fabricated biosensor at 4°C in PBS when not in use to maintain enzyme activity.

Measurement and Data Analysis: Perform amperometric measurements by applying a constant potential of +0.6 V vs. Ag/AgCl. Upon successive additions of glucose standard solutions, monitor the oxidation current of the generated hydrogen peroxide. The steady-state current is proportional to the glucose concentration. The biosensor demonstrates a linear response from 1 nM to 100 mM with a detection limit of 0.12 nM [26].

Protocol for FRET-Based Aptasensor for Sweat Lactate Detection

This protocol details a highly sensitive, non-invasive method for lactate quantification in sweat using a fluorescence-based aptasensor.

Materials and Reagents:

- L-lactate aptamer (5'-Biotin-TEG-GACGACGAGTAGCGCGTATGAATGCTTTTCTATGGAGTCGTC-3') [27]

- Core-Shell Upconversion Nanoparticles (CS-UCNPs: NaYF₄:Yb/Er@NaYF₄)

- Fe₃O₄-decorated MoS₂ (Fe₃O₄-MoS₂) nanosheets

- Polyethyleneimine (PEI) and Glutaraldehyde

- Tris-HCl buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4)

- Lactate standards (0-30 mM in artificial sweat matrix)

Procedure:

- Aptamer-Probe Conjugation: Functionalize CS-UCNPs with PEI. Incubate 1 nmol of biotinylated L-lactate aptamer with 1 mg of PEI-modified CS-UCNPs in Tris-HCl buffer for 2 hours at 37°C with gentle shaking.

- FRET Pair Assembly: Mix the aptamer-conjugated CS-UCNPs with 0.5 mg of Fe₃O₄-MoS₂ nanosheets. Incubate for 1 hour to allow close proximity (<10 nm) between the donor (UCNPs) and acceptor (MoS₂), establishing an efficient FRET system that quenches fluorescence at 545 nm.

- Sample Incubation: Add 50 µL of sweat sample (or lactate standard) to the FRET system. Incubate for 15 minutes at room temperature. Lactate binding induces aptamer conformational changes, increasing the donor-acceptor distance.

- Magnetic Separation: Place the reaction tube on a magnetic stand for 1 minute to separate the Fe₃O₄-MoS₂/aptamer complex. Transfer the supernatant containing the recovered fluorescence signal to a quartz cuvette.

- Fluorescence Measurement: Use a fluorescence spectrophotometer with 980 nm excitation. Measure the emission intensity at 545 nm. The fluorescence recovery is directly proportional to the lactate concentration in the sample.

Data Analysis: Generate a calibration curve by plotting fluorescence intensity at 545 nm against known lactate standard concentrations (0-30 mM). The aptasensor exhibits a broad linear range (R² = 0.9981) with an ultralow detection limit of 0.078 mM, enabling precise lactate quantification in sweat [27].

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Experimental Workflow for Biosensor Development and Application

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow from biosensor fabrication to metabolite monitoring in a wearable context.

Mechanism of Enzyme-Based Electrochemical Sensing

This diagram details the fundamental signaling pathway for enzyme-based electrochemical biosensors, specifically for glucose detection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful development of enzyme-based electrochemical biosensors requires carefully selected materials and reagents. The following table outlines essential components and their specific functions in biosensor fabrication.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Electrochemical Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Graphene Nanostructures | Enhances electron transfer, provides high surface area for biomolecule immobilization, improves sensitivity | Functional graphene sheets (FGS), graphene oxide (GO), reduced graphene oxide (rGO) [4] |

| Core-Shell UCNPs | Serves as fluorescence donor in FRET systems; enables near-infrared excitation minimizing background noise | NaYF₄:Yb/Er@NaYF₄ [27] |

| Fe₃O₄-MoS₂ Nanosheets | Acts as fluorescence quencher and provides magnetic separation capability in FRET-based biosensors | In-situ synthesized Fe₃O₄ on MoS₂ nanosheets [27] |

| Specific Aptamers | Provides high-affinity recognition for target analytes; offers advantages over enzymes including thermal stability | L-lactate aptamer (5'-Biotin-TEG-GACGACGAGTAGCGCGTATGAATGCTTTTCTATGGAGTCGTC-3') [27] |

| Glucose Oxidase (GOx) | Primary biorecognition element for glucose sensing; catalyzes glucose oxidation | From Aspergillus niger; typically immobilized via cross-linking or encapsulation [26] |

| Chitosan | Biocompatible polymer for enzyme immobilization; forms stable films on electrode surfaces | 1% w/v in dilute acetic acid; used for forming bionanocomposite films [26] |

Enzyme-based electrochemical biosensors for non-invasive sweat analysis represent a cutting-edge technological platform for continuous metabolite tracking. The integration of advanced nanomaterials like graphene and core-shell UCNPs has substantially improved the sensitivity, selectivity, and reliability of these devices [4] [27]. The experimental protocols outlined provide robust methodologies for developing biosensors capable of detecting clinically relevant biomarkers such as glucose and lactate at physiologically relevant concentrations in sweat.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on enhancing multiplexing capabilities to simultaneously monitor multiple biomarkers, improving long-term stability for extended monitoring periods, and addressing challenges related to individual variations in sweat composition [7] [4]. Furthermore, the integration of machine learning algorithms for data analysis and the development of closed-loop systems that provide real-time therapeutic interventions represent the next frontier in personalized healthcare [7]. As these technologies mature, wearable electrochemical biosensors are poised to revolutionize both clinical diagnostics and personal health monitoring, enabling proactive management of metabolic disorders and optimization of human performance.

Photoplethysmography (PPG) is an optical sensing technique widely employed in wearable biosensors for the non-invasive monitoring of vital signs. It functions by illuminating the skin and subcutaneous tissue using a light-emitting diode (LED) and subsequently measuring the intensity of light either transmitted through or reflected back from the tissue using a photodetector (PD) [28]. The fundamental physiological principle underpinning PPG is the modulation of light absorption by arterial blood volume changes synchronized with the cardiac cycle [28]. The resulting PPG waveform comprises a pulsatile alternating current (AC) component, attributable to cardiac-synchronous changes in arterial blood volume, and a quasi-constant direct current (DC) component, stemming from absorption by non-pulsatile arterial blood, venous blood, and static tissues such as bone and skin [28]. This simple yet powerful optical technique enables the extraction of a wealth of cardiovascular and physiological information, making it a cornerstone of modern continuous health monitoring research.

The adoption of PPG biosensors in research and clinical practice is experiencing significant growth, driven by the convergence of rising cardiovascular disease prevalence and advancements in wearable technology [29]. The market for these sensors is projected to grow from USD 648.5 million in 2025 to USD 3,064.8 million by 2035, reflecting a robust compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 16.8% [30]. This expansion is fueled by their integration into consumer electronics, particularly smartwatches, which constitute the largest product segment with a 42.8% value share [30]. For researchers, understanding the technical capabilities, limitations, and appropriate application protocols of PPG technology is paramount for designing robust studies in continuous health monitoring and drug development.

Quantitative Data and Performance Metrics

The performance and application landscape of PPG biosensors can be quantitatively assessed across market metrics, operational parameters, and technical specifications. The following tables provide a consolidated overview for researcher reference.

Table 1: PPG Biosensors Market and Application Metrics

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Value / Share | Context & Forecast |

|---|---|---|---|

| Market Size & Growth | Global Market Value (2025E) | USD 648.5 Million [30] | Projected to reach USD 3,064.8 Million by 2035 [30] |

| Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) | 16.8% (2025-2035) [30] | --- | |

| Application Segmentation | Leading Application | Cardiovascular Monitoring [29] | ~40% market share [29] |

| Fastest-Growing Application | Sleep & Stress Monitoring [29] | CAGR of 22% [29] | |

| Product Segmentation | Leading Product Type | Smart Watches [30] | 42.8% Value Share [30] |

| Leading Modality | Transmission Mode PPG [29] | 60% market share [29] |

Table 2: PPG Signal Components, Characteristics, and Research Applications

| Signal Component | Physiological Origin | Key Characteristics | Primary Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| AC Component (Pulsatile) | Arterial blood volume changes | Synchronized with heart rate; susceptible to motion artifacts [28] | Heart rate (HR), Heart rate variability (HRV), Pulse Wave Velocity (PWV), Blood Pressure estimation [28] |

| DC Component (Quasi-Constant) | Venous blood, non-pulsatile tissues, and average blood volume [28] | Varies slowly with respiration, vasomotion, and thermoregulation [28] | Blood Oxygen Saturation (SpO₂), Baseline tissue absorption [28] |

| Waveform Morphology | Vascular compliance and peripheral perfusion | Analyzed for systolic peak, diastolic peak, and dicrotic notch | Vascular aging assessment, Atherosclerosis risk, Anesthesia depth monitoring [28] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Standardized PPG Signal Acquisition for Vital Signs

This protocol outlines the procedure for acquiring research-grade PPG data from human subjects using a reflective-mode sensor, typical of wrist-worn wearables, for heart rate and pulse waveform analysis.

Objective: To obtain a clean, artifact-minimized PPG signal for the calculation of heart rate and analysis of waveform morphology. Materials: Research-grade PPG sensor module (with LED and photodetector), data acquisition (DAQ) system, computer with signal processing software, skin preparation supplies (e.g., alcohol swab), and a comfortable chair for the subject. Procedure:

- Sensor Preparation and Placement:

- Select an appropriate sensor site (e.g., volar wrist, fingertip). Ensure the site is free from tattoos, scars, or excessive hair that could interfere with signal quality [30].

- Clean the skin area with an alcohol swab and allow it to dry completely to optimize skin-sensor contact.

- Securely attach the PPG sensor to the skin using a medical-grade adhesive patch or strap, ensuring firm but comfortable contact without restricting blood flow.

Signal Acquisition and Baseline Recording:

- Instruct the subject to assume a seated, relaxed position with the sensor limb supported to minimize movement.

- Initiate data recording at a sampling rate of ≥ 100 Hz to adequately capture waveform details.

- Record a 5-minute baseline PPG signal while the subject remains at rest and breathing normally. This recording serves as the individual's physiological reference.

Data Quality Verification:

- Visually inspect the real-time signal or the recorded baseline for a clear, periodic waveform with a sharp systolic upstroke and a discernible diastolic peak/notch.

- Verify that the signal is free from significant motion artifacts (characterized by irregular, high-amplitude deflections) and baseline wander.

Protocol 2: PPG-Derived Heart Rate and Heart Rate Variability (HRV) Analysis

This protocol details the computational steps to extract heart rate and HRV metrics from a acquired PPG signal, which are critical biomarkers in cardiovascular research and drug development.

Objective: To compute beat-to-beat intervals (BBI), heart rate, and time-domain HRV parameters from a processed PPG signal. Materials: Processed PPG signal from Protocol 1, signal processing software (e.g., Python with SciPy/NumPy, MATLAB, Kubios HRV). Procedure:

- Pre-processing:

- Apply a band-pass filter (e.g., 0.5 Hz to 8 Hz) to the raw PPG signal to attenuate high-frequency noise and slow baseline drift.

- Normalize the signal to zero mean and unit variance.

Systolic Peak Detection:

- Implement a peak detection algorithm (e.g., based on amplitude threshold and minimum peak distance) to identify the location of each systolic peak (P_i) in the filtered PPG signal.

Parameter Calculation:

- Beat-to-Beat Intervals (BBI): Calculate the time difference between consecutive systolic peaks:

BBI_i = P_{i+1} - P_i. - Instantaneous Heart Rate: Compute the heart rate for each beat in beats per minute (bpm):

HR_i = 60 / BBI_i. - Time-Domain HRV: Calculate standard deviation of NN intervals (SDNN) and root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD) from the series of BBI.

- Beat-to-Beat Intervals (BBI): Calculate the time difference between consecutive systolic peaks:

Protocol 3: Investigating Physiological Response Using PPG

This protocol leverages the high temporal resolution of PPG to study physiological responses to interventions, such as a breath-hold maneuver, which can be a model for assessing autonomic function or drug effects.

Objective: To characterize the dynamic changes in heart rate and peripheral perfusion in response to a controlled physiological stressor. Materials: As in Protocol 1, plus a timer. Procedure:

- Pre-Intervention Baseline:

- Follow Protocol 1 to obtain a 5-minute resting baseline recording.

Controlled Intervention (e.g., Breath-Hold):

- At a predefined time, instruct the subject to take a normal inspiration and then hold their breath for a safe duration (e.g., 15-20 seconds). Record the start and end times of the breath-hold.

- Continue recording for a 5-minute recovery period post-intervention.

Data Analysis:

- Extract heart rate trends (as in Protocol 2) across the three phases: baseline, breath-hold, and recovery.

- Analyze the PPG waveform amplitude (AC component) as a proxy for peripheral blood volume changes.

- Statistically compare the average heart rate and waveform amplitude between the three phases to quantify the physiological response.

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflow for a standard PPG analysis and the signal pathway from physiological event to extracted metric, which is crucial for understanding experimental design and potential points of failure.

Diagram 1: PPG Data Analysis Workflow.

Diagram 2: PPG Signal Transduction Pathway.

The Researcher's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for PPG Experimentation

| Item / Solution | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Research-Grade PPG Sensor Module | Core component for signal acquisition; available in various wavelengths (Green: better SNR for HR, Red/IR: for SpO₂) [28]. |

| Flexible/Stretchable Substrate | Enables development of skin-conformal sensors (e.g., patches) that minimize motion artifacts and improve comfort for long-term studies [28] [5]. |

| Medical-Grade Adhesive | Secures the sensor to the skin site, ensuring consistent contact pressure, which is critical for signal stability and reproducibility [5]. |

| Data Acquisition (DAQ) System | Hardware interface for converting the analog photodetector signal into a digital format for software analysis; requires appropriate sampling rate and resolution [28]. |

| Signal Processing Software Library | (e.g., in Python/MATLAB): For implementing filtering, peak detection, and feature extraction algorithms to transform raw PPG data into research metrics [31]. |

| Calibration Phantom/Tissue Simulant | Used for bench-top validation of PPG sensor performance under controlled conditions that mimic different skin tones and tissue properties [30]. |

Microneedle (MN) technology has emerged as a transformative platform for minimally invasive access to dermal interstitial fluid (ISF), enabling continuous monitoring of biomarkers and therapeutic drugs. This capability is critical for advancing personalized medicine, particularly in managing chronic conditions like diabetes. By penetrating the skin's outermost stratum corneum (15-20 µm thick) while avoiding deeper pain receptors and capillaries, MNs facilitate painless sampling and sensing of ISF, which contains a rich profile of biomarkers, including glucose, metabolites, proteins, and nucleic acids, that closely correlate with blood concentrations [32] [33] [34]. The integration of MN technology with wearable biosensors represents a significant leap forward in closed-loop systems for real-time health monitoring and therapeutic intervention.

This article provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for leveraging MN technology in glucose and drug monitoring research, framed within the broader context of wearable biosensors for continuous health monitoring.

Technical Specifications of Representative MN Monitoring Systems

Table 1: Performance comparison of recent integrated MN-based monitoring systems

| System Feature | Integrated Glucose/Insulin System [32] | Dual-Sensor MCBM System [35] | Optical MN Sensors [36] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Continuous glucose monitoring & on-demand insulin delivery | Simultaneous glucose & metformin monitoring | Multiplexed biomarker detection via colorimetry, fluorescence, SERS |

| MN Array Architecture | 3×3 array (4 glucose-sensing electrodes, 8 insulin-release MNs) | 3D-printed dual-sensor MN with microchannels | Various structural designs (hollow, coated, hydrogel-forming) |

| Sensing Mechanism | Glucose oxidase electrochemical sensing | Nanoenzyme-based electrochemical sensing (Fe₂O₃/CuO for glucose, Fe₂O₃ for metformin) | Optical signal transduction (color change, fluorescence intensity, Raman scattering) |

| Drug Delivery Capability | 8 independently addressable insulin-loaded redox-responsive hydrogel MNs | None | Limited passive delivery possible with specific designs |

| Signal Processing | 12-bit ADC, Bluetooth Low Energy wireless transmission | Differential pulse voltammetry, Bluetooth transmission | Visual readout, smartphone imaging, spectral analysis |

| In Vivo Validation | Rat model, glycemic control demonstration | Rabbit skin model, diabetes management application | Mouse model, metabolite monitoring demonstration |

Table 2: Classification and characteristics of microneedle types for ISF access

| MN Type | Material Composition | Fabrication Methods | Key Advantages | Primary Monitoring Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid [34] | Metals (stainless steel, titanium), Silicon, Ceramics | Micromachining, Laser cutting, Etching | Create immediate microchannels; robust structure; can serve as electrodes | Skin pretreatment for subsequent ISF sampling; electrode implantation for continuous sensing |

| Coated [34] | Metal/Polymer base with coated biomolecules (enzymes, antibodies) | Dip-coating, Spray-coating, Layer-by-layer deposition | Direct integration of sensing elements; rapid dissolution upon insertion | Single-point measurement of specific analytes (e.g., glucose, cortisol) |

| Hollow [33] [34] | Silicon, Metals, Polymers | Micromolding, 3D printing, Two-photon polymerization | Active ISF extraction; continuous fluid sampling; larger sample volumes | Continuous ISF sampling for ex vivo analysis; integration with microfluidic systems |

| Dissolving [37] [34] | Biodegradable polymers (PVA, PVP, Hyaluronic acid, Carboxymethyl cellulose) | Micromolding, Casting | Self-disabling; minimal biohazard waste; controlled release of encapsulated reagents | Embedded reagent release for colorimetric/fluorescent detection; single-use applications |

| Hydrogel-Forming [36] [34] | Swellable polymers (PVA, PVP cross-linked) | Casting, Cross-linking polymerization | ISF extraction via swelling; continuous sampling capability; maintains structural integrity | Sustained ISF sampling for continuous monitoring; extended wear applications |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication of 3D-Printed Dual-Sensor Microneedles for Simultaneous Glucose and Metformin Monitoring

This protocol details the creation of a dual-sensor MN system for continuous monitoring of glucose and antidiabetic drugs (e.g., metformin) in ISF, based on validated research [35].

Materials and Equipment