Validating Neurostimulation Protocols: A Computational Modeling Approach for Enhanced Precision and Efficacy

This article provides a comprehensive examination of computational model validation for neurostimulation protocols, a critical step in translating theoretical simulations into reliable clinical and research applications.

Validating Neurostimulation Protocols: A Computational Modeling Approach for Enhanced Precision and Efficacy

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of computational model validation for neurostimulation protocols, a critical step in translating theoretical simulations into reliable clinical and research applications. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles underpinning model credibility, details advanced methodological workflows for application, addresses key troubleshooting and optimization challenges such as parameter personalization and handling biological variability, and establishes robust frameworks for validation and comparative analysis against experimental data. By synthesizing current literature and emerging trends, this review serves as a strategic guide for enhancing the predictive power and clinical feasibility of in-silico neurostimulation studies, ultimately aiming to improve reproducibility and therapeutic outcomes.

The 'Why' and 'What': Establishing the Bedrock for Credible Models

In the rapidly evolving field of computational neurostimulation, model validation represents a critical process for ensuring that virtual representations of neural systems accurately reflect biological reality. As defined by the American Academy of Actuaries and applied to computational neuroscience, model validation is "the practice of performing an independent challenge and thorough assessment of the reasonableness and adequacy of a model based on peer review and testing across multiple dimensions" [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals working with neurostimulation protocols, rigorous validation transforms theoretical models from speculative tools into reliable platforms for therapy optimization and device design.

The fundamental challenge driving the need for robust validation frameworks is the inherent complexity of neural systems and their interactions with electrical stimuli. Without proper validation, model risk—defined as the potential for misrepresenting intended relationships through flawed implementation or misuse—can lead to failed clinical translations and costly research dead ends [1]. This guide examines the key concepts, terminology, and experimental approaches defining model validation in neurostimulation research, providing a comparative analysis of emerging methodologies that are shaping the future of personalized neuromodulation therapies.

Core Principles of Model Validation

Effective model validation in neurostimulation research rests on eight core principles established by the North American CRO Council and adapted for computational neuroscience applications [1]:

- Model Design Consistency: The model construction must align with its intended purpose, whether for predicting neural tissue damage, optimizing stimulation parameters, or understanding fundamental mechanisms.

- Independent Validation: The validation process must be conducted separately from model development to eliminate confirmation bias.

- Designated Ownership: A single individual should be accountable for validation results and serve as the point of contact.

- Appropriate Governance: A formal framework must define roles, responsibilities, and maintenance procedures.

- Proportionality: Validation efforts should focus on areas of greatest materiality and complexity.

- Component Validation: Input data, computational logic, and output formats each require specific validation approaches.

- Limitation Acknowledgement: The inherent constraints of the validation process must be explicitly documented.

- Comprehensive Documentation: All processes, findings, and limitations must be recorded for future reference.

In Bayesian inference frameworks commonly used in neurostimulation research, validation extends beyond computational accuracy to assess whether modeling assumptions adequately capture relevant system behaviors [2]. This involves quantifying error in posterior expectation value estimates and performing posterior retrodictive checks to determine how well the posterior distribution recovers features of the observed data [2].

Table 1: Core Components of Model Validation in Neurostimulation

| Validation Component | Key Questions | Common Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Input Validation | Are assumptions biologically plausible? Is source data reliable? | Expert judgment, benchmarking against literature, back-testing [1] |

| Calculation Validation | Does model logic correctly incorporate inputs? Are computations stable? | Sensitivity testing, dynamic validation, boundary case testing [1] |

| Output Validation | Do results align with experimental observations? Is presentation clear? | Comparison with existing models, historical back-testing, peer review [1] |

Comparative Analysis of Validation Approaches

Cardiovascular Neurostimulation Model

The Lehigh University team developed a computationally tractable model of the human cardiovascular system that integrates the processing centers in the brain that control the heart [3]. This model was specifically designed to predict hemodynamic responses following atrial fibrillation (AFib) onset and guide neurostimulation dosage decisions.

Validation Methodology: The team employed clinical data comparison, validating their model against real-patient data for heart rate, stroke volume, and blood pressure metrics [3]. The model's prediction of the atrioventricular node as a strong stimulation candidate provided additional validation, as this area is already an established target for ablation therapy [3].

Key Advantage: The model's computational efficiency makes it suitable for rapid testing and potential real-time use, creating a practical "digital twin" framework for personalized cardiac care [3].

Digital Twin Framework for Viscerosensory Neurostimulation

A 2025 study established a digital twin approach for predictive modeling of neuro-hemodynamic responses during viscerosensory neurostimulation [4]. This framework focuses on the computational role of the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) in the brainstem, capturing stimulus-driven hemodynamic perturbations through low-dimensional latent space representation of neural population dynamics [4].

Validation Methodology: Researchers implemented simultaneous extracellular single-unit NTS recordings and femoral arterial blood pressure measurements in rats (n=10) during electrical pulse train stimulation [4]. They analyzed cross-correlations and shared variances among NTS neurons (n=192), finding significantly higher couplings in measured data (83% shared variance) compared to dummy data (27% shared variance), validating that heterogeneous responses stem from interconnected neural populations [4].

Key Advantage: This approach enables individually optimized predictive modeling by leveraging neuro-hemodynamic coupling, potentially facilitating closed-loop neurostimulation systems for precise hemodynamic control [4].

Machine Learning Model for Tissue Damage Prediction

NeurostimML represents a novel machine learning approach for predicting electrical stimulation-induced neural tissue damage [5]. This model addresses limitations of the traditional Shannon equation, which relies on only two parameters and has demonstrated 63.9% accuracy compared to the Random Forest model's 88.3% accuracy [5].

Validation Methodology: Researchers compiled a database with 387 unique stimulation parameter combinations from 58 studies spanning 47 years [5]. They employed ordinal encoding and random forest for feature selection, comparing four machine learning models against the Shannon equation using k-fold cross-validation [5]. The selected features included waveform shape, geometric surface area, pulse width, frequency, pulse amplitude, charge per phase, charge density, current density, duty cycle, daily stimulation duration, daily number of pulses delivered, and daily accumulated charge [5].

Key Advantage: NeurostimML incorporates multiple stimulation parameters beyond charge-based metrics, enabling more reliable prediction of tissue damage across diverse neuromodulation applications [5].

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Neurostimulation Validation Approaches

| Model/Platform | Primary Validation Method | Key Performance Metrics | Computational Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lehigh Cardiovascular Model [3] | Clinical data comparison | Matched heart rate, stroke volume, and blood pressure to patient data | Low computational cost; suitable for rapid testing |

| Digital Twin NTS Framework [4] | Latent space analysis of neural populations | 83% shared variance in neuronal responses; accurate BP prediction | Medium requirements for latent space derivation |

| NeurostimML Random Forest [5] | k-fold cross-validation against historical data | 88.3% accuracy in damage prediction vs. 63.9% with Shannon equation | Higher requirements for training; efficient prediction |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

AI-Guided Neural Control Protocol

A detailed protocol for artificial intelligence-guided neural control in rats provides a framework for validating closed-loop neurostimulation systems [6]. This approach integrates deep reinforcement learning to drive neural firing to desired states, offering a validation methodology for neural control algorithms [6].

Key Steps:

- Perform chronic electrode implantations in rats to facilitate long-term neural stimulation

- Implement thalamic infrared neural stimulation and cortical recordings

- Apply deep reinforcement learning for closed-loop control of neural firing states

- Compare model-predicted outcomes with empirical neural recordings

This protocol emphasizes adherence to local institutional guidelines for laboratory safety and ethics throughout the validation process [6].

Multi-Target Electrical Stimulation Validation

Research published in Scientific Reports details the simulation and experimental validation of a novel noninvasive multi-target electrical stimulation method [7]. This approach addresses the challenge of achieving synchronous multi-target accurate electrical stimulation in deep brain regions.

Experimental Validation Workflow:

- Establish a simulation model based on magneto-acoustic coupling effect and phased array focusing technology

- Create an experimental system for transcranial magneto-acoustic coupling electrical stimulation (TMAES)

- Compare simulated and experimental results for multi-target focused electrical field distribution

- Quantify focal point size (achieving average of 5.1 mm per target) and location accuracy

The study demonstrated that multi-target TMAES could non-invasively achieve precise focused electrical stimulation of two targets, with flexibility to adjust location and intensity through parameter modification [7].

Model Validation Workflow in Neurostimulation Research

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The execution and validation of neurostimulation models requires specific experimental setups and computational tools. The following table details key research solutions employed in the featured studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Neurostimulation Model Validation

| Reagent/Solution | Function in Validation | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Chronic Electrode Implants [6] | Facilitate long-term neural stimulation and recording in animal models | AI-guided neural control protocols in rats [6] |

| Extracellular Recording Systems [4] | Capture single-unit neural activities during stimulation | NTS neuronal population recording (192 neurons across 10 rats) [4] |

| Hemodynamic Monitoring [3] [4] | Measure cardiovascular responses to neurostimulation | Femoral arterial BP measurement in rat models [4] |

| Finite Element Modeling Software [8] | Simulate electric field distributions in neural tissue | Patient-specific computational models of spinal cord stimulation [8] |

| Machine Learning Algorithms [5] | Predict tissue damage and optimize stimulation parameters | Random Forest classification for damage prediction [5] |

| Digital Twin Platforms [3] [4] | Create virtual replicas for personalized prediction | Cardiovascular digital twin for AFib therapy optimization [3] |

Signaling Pathways in Neurostimulation Validation

The validation of neurostimulation models requires understanding of key neural pathways involved in stimulus response. The nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) pathway has been identified as crucial for cardiovascular control during viscerosensory neurostimulation [4].

NTS Pathway in Neurostimulation Response

The validation of computational models in neurostimulation research represents a multifaceted process that integrates computational techniques with experimental verification. As the field progresses toward more personalized medicine approaches, including digital twin frameworks [3] [4], robust validation methodologies become increasingly critical for clinical translation. The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that while validation approaches may differ across applications—from cardiovascular control to neural tissue damage prediction—they share common foundational principles that prioritize biological plausibility, computational accuracy, and experimental corroboration.

Future directions in neurostimulation model validation will likely involve greater integration of machine learning techniques [5], more sophisticated digital twin platforms [4], and standardized validation frameworks that can keep pace with rapid technological innovations. For researchers and drug development professionals, adhering to rigorous validation principles remains essential for transforming computational models from theoretical constructs into reliable tools for advancing neuromodulation therapies.

Computational models have become indispensable tools in the development and optimization of neurostimulation therapies, bridging the gap between theoretical concepts and clinical applications. The credibility of these models hinges on the faithful integration of two core components: accurate geometric representations of anatomy and robust physics-based simulations of underlying phenomena. This guide compares the performance of predominant modeling approaches used in the field, from traditional methods to modern machine learning-assisted techniques, providing researchers with a framework for validating models within neurostimulation protocol research.

In neurostimulation, computational models provide a critical platform for investigating mechanisms of action and optimizing therapy, fulfilling roles that would be difficult, time-consuming, or ethically challenging to perform through experimentation alone [9]. Their development is a multi-disciplinary endeavor, requiring the synthesis of anatomical geometry, the physics of bioelectric fields, and the neurophysiology of neural targets. A model's credibility is determined by its ability to not just replicate empirical data, but to predict outcomes in novel scenarios, such as a new patient anatomy or a previously untested stimulation parameter. This is particularly vital as the field advances toward multi-target therapies for complex neurological diseases, where intuitive parameter selection becomes impossible [10]. The following sections dissect the core components of these models, providing a comparative analysis of methodologies and the data that underpins their validation.

Comparative Analysis of Geometric Representation Methodologies

The choice of how to represent anatomy digitally is a foundational step that directly impacts a model's computational cost, biological fidelity, and ultimate utility. The table below compares the most common geometric representations used in computational models for neurostimulation.

Table 1: Comparison of Geometric Representation Methodologies in Computational Modeling

| Representation Type | Core Description | Typical Data Sources | Advantages | Limitations | Exemplary Use-Cases in Neurostimulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesh-Based (e.g., Finite Element Meshes) | 3D geometry discretized into small elements (e.g., tetrahedra, hexahedra); physics are solved over this mesh. | MRI, CT, histological cross-sections [9] | High physical accuracy; well-established mathematical foundation; suitable for complex, inhomogeneous domains. | Very high computational cost; model construction is labor-intensive; solution time scales with mesh resolution. | Patient-specific models of the spinal cord for predicting electric field spread in SCS [9]. |

| Point Clouds & Voxels | Unstructured set of points in 3D space (point clouds) or a 3D grid of volumetric pixels (voxels). | 3D scanning, MRI/CT segmentation | Simpler to generate than meshes; directly output from many imaging modalities. | Lacks connectivity information; can be high-dimensional; not directly suitable for physics simulation without further processing. | Initial digital capture of anatomical structures before conversion to a simulation-ready format. |

| Implicit/SDF (Signed Distance Function) | A continuous function that defines the distance from any point in space to a surface; the surface is the set of points where SDF=0 [11]. | CAD models, algorithmic generation | Compact, continuous representation; easy to perform Boolean operations and check collisions. | Less intuitive for direct manipulation; can be computationally expensive to evaluate for complex shapes. | Representing smooth, synthetic geometries in preliminary design explorations for implantable leads. |

| Latent Representations (via LGM) | A low-dimensional vector learned by an AI model (e.g., VAE) that encodes the essential features of a high-dimensional geometry [11]. | Large datasets of existing 3D geometries (e.g., meshes) | Extremely compact (e.g., 512 dimensions); enables fast design optimization and surrogate modeling; filters out mesh noise. | Requires significant upfront investment to train the model; "black box" nature can reduce interpretability. | Rapidly exploring the design space of a new component or optimizing a geometry within a learned, valid manifold [11]. |

Comparative Analysis of Physics Integration and Solution Methods

Once the geometry is defined, the physical principles governing the system must be integrated and solved. The choice of solution method involves a trade-off between computational speed and physical rigor.

Table 2: Comparison of Physics Integration and Solution Methods in Neurostimulation Models

| Solution Method | Underlying Principle | Typical Software/Tools | Advantages | Limitations | Key Fidelity Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finite Element Method (FEM) | Solves partial differential equations (PDEs) by dividing the domain into small elements and finding approximate solutions per element [9]. | COMSOL, Abaqus, FEniCS | High accuracy for complex geometries and material properties; gold standard for electric field calculations. | Computationally intensive; requires expertise in mesh generation and convergence testing. | Electric field strength accuracy, convergence on mesh refinement. |

| Finite Volume Method (FVM) | Solves PDEs by calculating fluxes across the boundaries of control volumes. | OpenFOAM, ANSYS Fluent | Conserves quantities like mass and momentum by construction; robust for fluid dynamics. | Less common for bioelectric problems compared to FEM. | Conservation property adherence, solution stability. |

| Hodgkin-Huxley Formalism | A set of nonlinear differential equations that describes how action potentials in neurons are initiated and propagated [9]. | NEURON, Brian, custom code | Biologically realistic model of neuronal excitability; can model ion channel dynamics. | High computational cost at scale; requires detailed knowledge of channel properties. | Action potential shape accuracy, firing rate prediction. |

| Data-Driven FEM (DD-FEM) | A framework merging traditional FEM structure with data-driven learning to enhance scalability and adaptability [12]. | Emerging/Research Codes | Aims for FEM-level accuracy with reduced computational cost; potential for broader generalization. | Emerging methodology; lacks the established theoretical guarantees of traditional FEM [12]. | Generalization across boundary conditions, extrapolation accuracy in time/space [12]. |

| Surrogate Modeling (e.g., with Gaussian Processes) | Trains a lightweight statistical model on data generated from a high-fidelity simulator (e.g., FEM) to make fast predictions [11]. | GPy, scikit-learn, MATLAB | Extremely fast evaluation; built-in uncertainty quantification (e.g., confidence intervals) [11]. | Accuracy is limited by the training data; may not extrapolate well outside the training domain. | Prediction error vs. ground truth simulator, quality of uncertainty estimates. |

Validating the Integrated Model: Protocols and Performance Metrics

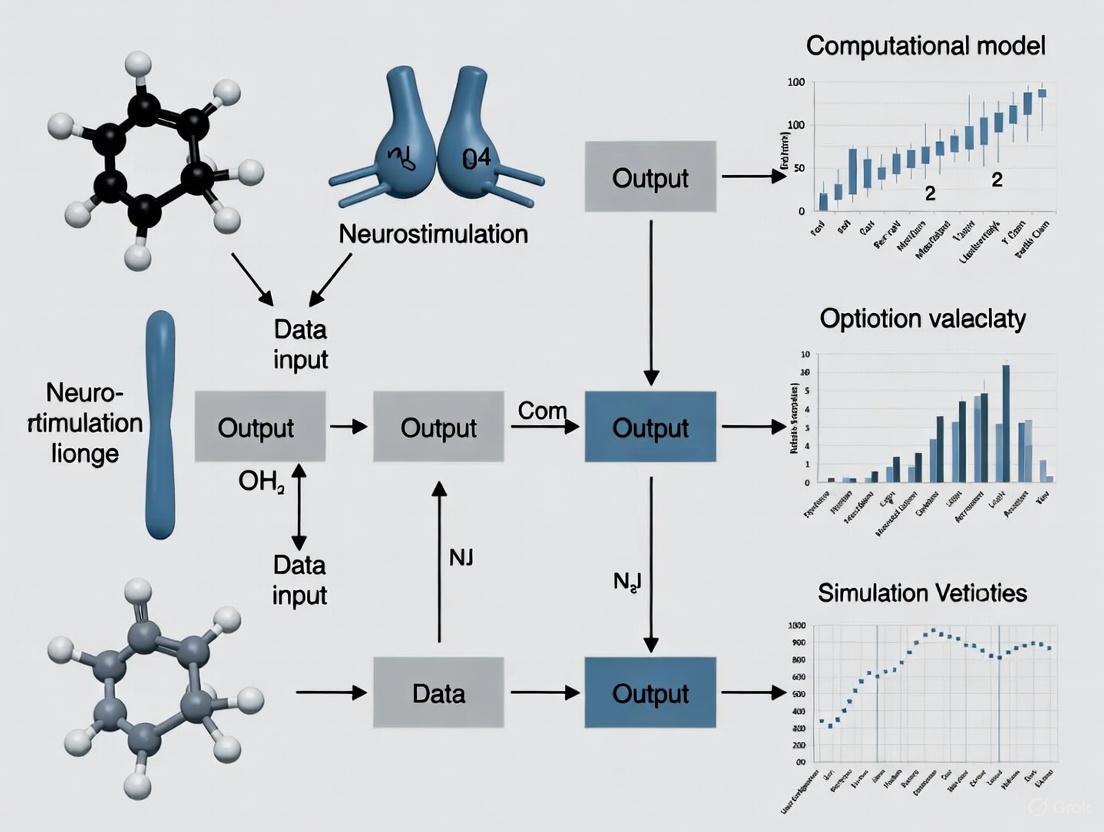

An integrated model combining geometry and physics is only as good as its validation. This process involves comparing model predictions against experimental and clinical data. The following diagram illustrates a standard workflow for building and validating a neurostimulation model, incorporating the components discussed in the previous sections.

Model Development and Validation Workflow

Key Validation Experiments and Performance Data

The credibility of a model is quantified by its performance against validation benchmarks. The table below summarizes key experimental protocols and the resulting performance data from recent credible computational models, particularly in the context of neurostimulation.

Table 3: Experimental Validation Protocols and Model Performance Benchmarks

| Validation Experiment | Experimental Protocol & Workflow | Key Outcome Measures | Reported Model Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular Neurostimulation (AFib) | 1. Develop closed-loop model integrating cardiovascular system & brain neurophysiology.\n2. Input clinical AFib episode data.\n3. Simulate neurostimulation and predict hemodynamic response.\n4. Compare predictions to empirical patient data [13]. | Heart rate (HR), stroke volume (SV), blood pressure (BP) profiles [13]. | Model output showed "robust concordance" with empirical patient data; identified AV node as a key neurostimulation target, aligning with clinical ablation practice [13]. |

| Spinal Cord Stimulation (SCS) for Pain | 1. Create patient-specific FEM model from medical images.\n2. Simulate electric field for a given lead design and stimulus.\n3. Use axon cable models to predict fiber activation.\n4. Correlate predicted activation with patient-reported pain relief [9]. | Neural activation thresholds of dorsal column fibers, spatial extent of activation, clinical pain ratings. | Models have "dramatically" improved lead designs and programming procedures; used commercially to focus stimulation on desired targets [9]. |

| SCS for Motor Control | 1. Couple electromagnetic model with neurophysiology.\n2. Simulate epidural stimulation and predict which neural pathways are recruited.\n3. Validate predictions via electrophysiology in animal models [8]. | Recruitment of sensory afferents vs. motor neurons, EMG responses, limb movement kinematics. | Models predicted and experiments confirmed that SCS primarily recruits large sensory afferents, not gray matter cells directly [8]. Model-driven biomimetic bursts restored movement in rats, monkeys, and humans [9]. |

| Surrogate Modeling via LGM | 1. Pre-train a Large Geometry Model (VAE) on millions of geometries.\n2. Encode new designs into a low-dimensional latent vector (z).\n3. Train a Gaussian Process regressor to map latent vector (z) to performance metric (c).\n4. Optimize in latent space and decode to full geometry [11]. | Prediction error of performance metrics (e.g., drag coefficient), geometric reconstruction accuracy. | Approach reduces overfitting risk vs. direct mesh-based models; provides uncertainty quantification; enables efficient high-dimensional design optimization [11]. |

Building and validating credible computational models requires a suite of specialized "research reagents" – both digital and physical.

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Resources for Computational Neurostimulation Research

| Tool/Reagent | Category | Primary Function in Research | Representative Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Imaging Data | Data | Provides the anatomical geometry for constructing patient-specific or population-average models. | MRI, CT scans; essential for defining model geometry and assigning tissue boundaries [9]. |

| Volume Conductor Model | Software/Algorithm | Computes the distribution of extracellular electric potentials generated by neurostimulation in complex tissues [9]. | Often implemented with Finite Element Method (FEM) software; the core of the physics simulation. |

| Hodgkin-Huxley Type Models | Software/Algorithm | Simulates the response of individual neurons or axons to the applied electric field, predicting action potential generation [9]. | Implemented in platforms like NEURON; adds neurophysiological realism to the physical model. |

| Tissue Electrical Properties | Data | Critical input parameters for the volume conductor model that significantly influence the predicted electric field. | Conductivity values for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), gray matter, white matter, and bone [9]. |

| Large Geometry Model (LGM) | AI Model | Learns a compact, low-dimensional representation of complex geometries to accelerate design and surrogate modeling [11]. | A pre-trained variational autoencoder (VAE); requires a large dataset of geometries for training. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) Regressor | Software/Algorithm | A lightweight machine learning model used as a surrogate for expensive simulations; provides fast predictions with uncertainty estimates [11]. | Used after an LGM to map latent geometric vectors to performance metrics. |

The journey toward a credible computational model in neurostimulation is a structured integration of precise geometry and robust physics. As evidenced by the comparative data, there is no single best approach; rather, the choice depends on the specific research question, balancing fidelity with computational feasibility. Traditional FEM-based biophysical models remain the gold standard for mechanistic insight and patient-specific prediction, while emerging AI-driven methods like LGMs and surrogate models offer transformative potential for rapid exploration and optimization of neurostimulation therapies. Ultimately, rigorous validation against experimental and clinical data is the non-negotiable final step that confers credibility, transforming a complex simulation into a trusted tool for scientific discovery and clinical innovation.

In computational neurostimulation, the transition from theoretical models to effective clinical protocols is fraught with uncertainties that stem directly from unvalidated assumptions. Model validation provides the critical framework for testing these assumptions, ensuring that computational predictions translate to reliable, effective neuromodulation treatments. Without rigorous validation, even the most sophisticated models risk being guided by unverified premises, leading to variable patient outcomes and failed clinical translations [14] [15].

The field of neurostimulation is experiencing rapid growth, with the global market for neurostimulation devices projected to reach USD 23.24 billion by 2034, expanding at a CAGR of 12.84% [16]. This growth is paralleled by an increasing recognition of neural variability not as noise to be minimized, but as a fundamental functional feature that must be accounted for in personalized stimulation protocols [17]. This shift necessitates advanced validation approaches that can address both inter-individual and intra-individual variability in response to non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS).

This guide examines the core methodologies for addressing model uncertainties in neurostimulation research, providing a structured comparison of validation techniques, experimental protocols, and computational tools essential for developing reliable, clinically translatable neuromodulation interventions.

Theoretical Foundation: From Neural Variability to Personalized Protocols

The Probabilistic Framework for Neurostimulation

Traditional neurostimulation approaches often employed a "one-size-fits-all" methodology, which ignored fundamental biological variations between individuals. Contemporary research demonstrates that neural variability serves as a core functional property that underpins brain flexibility and adaptability [17]. This variability manifests across multiple dimensions:

- Inter-individual variability: Structural and functional brain differences between subjects

- Intra-individual variability: Fluctuating brain states within the same individual

- State-dependent plasticity: Variation in response to stimulation based on current neural activity

A probabilistic framework for personalization incorporates this variability through detailed brain activity recordings and advanced analytical techniques, optimizing non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) protocols for individual brain states [17]. This approach represents a paradigm shift from minimizing neural variability to strategically leveraging it for improved treatment outcomes.

The Closed-Loop Neurostimulation Paradigm

Closed-loop systems address fundamental uncertainties in neurostimulation by continuously adapting stimulation parameters based on real-time biomarkers. This approach contrasts sharply with traditional open-loop systems, where stimulation parameters remain fixed without regard to ongoing neural activity [15].

Table 1: Comparison of Open-Loop vs. Closed-Loop Neurostimulation Systems

| Feature | Open-Loop Systems | Closed-Loop Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter Adjustment | Fixed based on prior empirical evidence | Dynamically adjusted based on real-time feedback |

| Brain State Consideration | No accommodation for non-stationary brain activities | Continuously monitors and responds to brain state fluctuations |

| Individualization | Limited personalization capabilities | Highly personalized through continuous optimization |

| Validation Requirements | Primarily model-based assumptions | Requires real-time biomarker validation |

| Clinical Flexibility | Rigid protocol structure | Adapts to individual patient responses |

The fundamental architecture of closed-loop systems follows a control engineering paradigm where the brain represents the "plant" whose state is constantly monitored via treatment response biomarkers [15]. These biomarkers, recorded through tools like fMRI or EEG, serve as proxies for the current brain state, which is compared against a desired state, with the difference driving the optimization of stimulation parameters through a dedicated controller.

Core Methodologies: Validation Techniques for Neurostimulation Models

Foundational Model Validation Approaches

Validation techniques provide the critical foundation for testing model assumptions and quantifying prediction uncertainties in neurostimulation research:

Holdout Validation Methods involve partitioning data into distinct subsets for training and testing models. The train-test split divides data into two parts (typically 70-80% for training, 20-30% for testing), while the train-validation-test split creates three partitions (e.g., 60% training, 20% validation, 20% testing) to avoid overfitting during parameter tuning [14]. For smaller datasets (common in neurostimulation research with limited subject pools), holdout methods may produce unstable estimates, necessitating more advanced techniques.

Cross-Validation addresses limitations of holdout methods by partitioning the dataset into multiple folds. The model is trained on combinations of these folds and tested on the remaining fold, repeating this process multiple times. This approach provides more robust performance estimates, especially valuable for detecting overfitting in complex neurostimulation models with limited data [14] [18].

Advanced Validation Frameworks for Neurostimulation

Beyond foundational methods, neurostimulation research requires specialized validation approaches:

Real-Time fMRI (rtfMRI) Validation integrates brain stimulation with simultaneous neuroimaging to establish closed-loop tES-fMRI systems for individually optimized neuromodulation. This methodology addresses the critical challenge of inter- and intra-individual variability in response to NIBS [15]. The system optimizes stimulation parameters by minimizing differences between the model of the current brain state and the desired state, with the objective of maximizing clinical outcomes.

Brain-State-Specific Validation incorporates the understanding that stimulation effects are not uniform but depend on the underlying brain state at the time of stimulation. This approach requires measuring baseline brain states and customizing stimulation protocols accordingly, moving beyond static models to dynamic, state-dependent validation frameworks [17].

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Addressing Key Uncertainties

Closed-Loop tES-fMRI Experimental Protocol

The integration of transcranial electrical stimulation (tES) with real-time fMRI represents a cutting-edge methodology for validating and optimizing neurostimulation protocols:

Objective: To establish a closed-loop system that individually optimizes tES parameters based on real-time fMRI biomarkers of target engagement [15].

Equipment and Setup:

- MRI-compatible tES device with real-time parameter control

- 3T MRI scanner with capability for real-time BOLD signal processing

- Biomarker detection software for continuous monitoring of target brain regions

- Closed-loop controller hardware/software for parameter optimization

Procedure:

- Baseline Assessment: Acquire 10-minute resting-state fMRI to identify individual functional connectivity patterns.

- Target Identification: Define target brain regions based on individual functional connectivity maps.

- Controller Setup: Implement optimization algorithm with predefined desired brain state.

- Stimulation Phase: Apply tES while continuously monitoring BOLD signal in target regions.

- Parameter Adjustment: Dynamically adjust stimulation intensity (0.5-2.0 mA) and location based on error signal between current and desired brain state.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 4-5 until predefined error threshold is reached or maximum iteration count is completed.

- Outcome Assessment: Evaluate both neural target engagement and behavioral/cognitive outcomes.

Validation Metrics: Target engagement magnitude, stability of maintained brain state, behavioral correlation with target engagement, and comparison to open-loop stimulation [15].

Probabilistic Personalization Protocol for NIBS

This protocol addresses individual variability by incorporating probabilistic frameworks into neurostimulation personalization:

Objective: To develop personalized NIBS protocols that account for inter-individual and intra-individual variability through probabilistic modeling [17].

Equipment and Setup:

- High-density EEG or fMRI equipment for brain state recording

- NIBS device (TMS, tDCS, or tACS) with neuronavigation capability

- Advanced analytical software for variability indices calculation

- Machine learning algorithms for probabilistic model training

Procedure:

- Multi-Modal Assessment: Collect structural MRI, functional connectivity (resting-state fMRI), and neurophysiological measurements (TMS-evoked potentials).

- Variability Quantification: Calculate neural variability indices through repeated measurements across multiple sessions.

- Model Training: Develop probabilistic models linking individual neural features to stimulation outcomes using machine learning.

- Protocol Optimization: Customize stimulation parameters (location, intensity, timing) based on individual probabilistic predictions.

- Validation: Test model predictions against actual outcomes in iterative refinement cycles.

- Longitudinal Tracking: Monitor changes in neural variability and adjust protocols accordingly.

Validation Metrics: Precision of outcome predictions, reduction in inter-individual response variability, stability of effects across sessions, and generalizability across clinical populations [17].

Computational Tools: The Research Toolkit for Model Validation

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Toolkit for Neurostimulation Model Validation

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Validation | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurostimulation Devices | Clinical-grade tDCS (Activadose), TMS with neuronavigation | Deliver precisely controlled stimulation for testing model predictions | Ensure compatibility with imaging equipment; verify precision of targeting |

| Neuroimaging Systems | Real-time fMRI, high-density EEG, fNIRS | Provide biomarkers for target engagement and treatment response | Balance spatial vs. temporal resolution based on validation objectives |

| Computational Modeling Platforms | Finite element head models, neural mass models | Simulate electric field distributions and neural population dynamics | Incorporate individual anatomical data; validate against empirical measurements |

| Closed-Loop Control Systems | Custom MATLAB/Python toolboxes, specialized neurotechnology | Enable real-time adjustment of stimulation parameters | Optimize latency for effective closed-loop intervention; ensure robust signal processing |

| Data Analysis Frameworks | Machine learning libraries, statistical packages | Identify patterns, build predictive models, quantify uncertainties | Address multiple comparison problems; implement appropriate cross-validation |

Emerging Technologies in Validation Research

Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) are advancing beyond motor restoration to include emotional regulation and cognitive enhancement, providing new avenues for validating neurostimulation models. Recent developments include Neuralink's human implants that enable thought-controlled external devices, representing sophisticated platforms for closed-loop validation [16].

AI-Powered Diagnostic Tools leverage machine learning to analyze vast amounts of patient data, offering personalized treatment recommendations and creating new validation paradigms through predictive modeling of stimulation outcomes [16] [19].

Comparative Analysis: Validation Outcomes Across Modalities

Quantitative Comparison of Validation Approaches

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Neurostimulation Validation Methods

| Validation Method | Individualization Capacity | Implementation Complexity | Evidence Strength | Clinical Translation Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-Size-Fits-All | Low | Low | Limited, highly variable outcomes | Poor, declining acceptance |

| Holdout Validation | Medium | Low to Medium | Moderate, dependent on dataset size | Moderate for large datasets |

| Cross-Validation | Medium to High | Medium | Strong, robust performance estimates | Good for protocol optimization |

| Closed-Loop rtfMRI | High | High | Emerging, highly promising | Excellent, though resource-intensive |

| Probabilistic Framework | High | High | Theoretical support, growing empirical | Excellent long-term potential |

Impact of Proper Validation on Clinical Outcomes

The critical importance of addressing model uncertainties through rigorous validation is demonstrated by comparative clinical outcomes:

Treatment-Resistant Depression: The Stanford neuromodulation therapy (SNT) paradigm utilizing individualized functional connectivity-guided targeting through resting-state fMRI demonstrated significantly improved outcomes compared to sham stimulation [15]. This approach highlights how validating the assumption that individual connectivity differences matter can dramatically impact clinical efficacy.

Chronic Pain Management: Spinal cord stimulation systems employing validated closed-loop approaches provide more consistent therapeutic effects compared to open-loop systems. Abbott's BurstDR technology demonstrated sustained relief for chronic back and leg pain, with 91% of patients preferring it over traditional methods after long-term use [19].

Parkinson's Disease: Medtronic's BrainSense Adaptive deep brain stimulation system, which received CE mark approval in 2025, uses sensing-enabled technology to provide personalized, closed-loop stimulation, representing a significant advancement over static stimulation paradigms [19].

Visualizing Workflows: Signaling Pathways and Experimental Frameworks

Closed-Loop Neurostimulation Workflow

Figure 1: Closed-Loop Neurostimulation Control Framework

Model Validation Methodology Decision Pathway

Figure 2: Model Validation Methodology Selection

The progression from unvalidated assumptions to rigorously tested computational models represents the critical path toward effective, reliable neurostimulation therapies. The evidence clearly demonstrates that models acknowledging and incorporating neural variability through probabilistic frameworks and closed-loop validation outperform traditional one-size-fits-all approaches [17] [15]. As the neurostimulation device market advances toward USD 23.24 billion by 2034 [16], the value of comprehensive model validation will only increase, particularly with emerging technologies like brain-computer interfaces and AI-powered diagnostics creating new opportunities for personalized neuromodulation.

The future of neurostimulation research lies in developing increasingly sophisticated validation frameworks that can address the multifaceted uncertainties inherent in computational models of brain function and stimulation effects. By implementing the comprehensive validation methodologies outlined in this guide—from basic holdout techniques to advanced closed-loop systems—researchers can systematically address model uncertainties, leading to more predictable outcomes and successful translations from computational models to clinical applications that reliably improve patient lives.

The Critical Role of Validation in Bridging In-Silico Findings and Real-World Outcomes

In silico methods, comprising biological experiments and trials carried out entirely via computer simulation, represent a transformative approach across biomedical research and development [20]. These computational techniques span from molecular modeling and whole-cell simulations to sophisticated virtual patient trials for medical devices and neurostimulation therapies [20] [21]. As these methods generate increasingly complex predictions, the critical challenge lies in establishing robust validation frameworks that ensure computational findings reliably translate to real-world biological and clinical outcomes. Without rigorous validation, in silico predictions remain theoretical exercises rather than trustworthy evidence for decision-making.

The validation imperative is particularly acute in neurostimulation research, where computational models simulate interactions between medical devices and the human nervous system [22]. These simulations aim to predict everything from cellular responses to treatment efficacy across diverse patient populations. Bridging this gap from digital prediction to physical reality demands meticulous validation protocols that verify models against experimental and clinical data, quantify uncertainties, and establish credibility for specific contexts of use [21]. This article examines the methodologies, standards, and evidence frameworks essential for transforming in silico models from intriguing hypotheses into validated tools for scientific discovery and clinical application.

Validation Frameworks and Regulatory Standards

Credibility Assessment Frameworks

Regulatory agencies have established structured approaches for assessing computational model credibility. The FDA's Credibility Assessment Framework provides guidance for evaluating models based on risk categorization—whether the computational model presents low, moderate, or high risk to regulatory decision-making [21]. This framework aligns with the ASME V&V 40 standard, which offers a structured approach to verification and validation of computational models used in medical applications [21]. These guidelines emphasize that model credibility depends not on universal validity but on sufficiency for the specific context of use, requiring researchers to define the model's intended purpose explicitly before establishing validation requirements.

The three-pillar model assessment framework endorsed by regulatory agencies encompasses model verification, validation, and uncertainty quantification [21]. Verification ensures that computational models correctly implement their intended mathematical representations through code verification, mesh convergence studies, and numerical accuracy assessments. Validation demonstrates accurate representation of real-world phenomena through comparison with experimental data, clinical outcome correlation, and sensitivity analysis across parameter ranges. Uncertainty quantification involves managing model parameter uncertainty from variability in material properties, model structure uncertainty from mathematical limitations, and numerical uncertainty from computational approximations.

Application in Medical Device Development

For medical device development, the Medical Device Development Tools (MDDT) program has created a pathway for qualifying computational models as regulatory-grade tools that multiple sponsors can use [21]. This program facilitates the acceptance of in silico evidence in regulatory submissions, as demonstrated by the VICTRE breast imaging simulation study, which the FDA accepted as evidence supporting imaging device performance, effectively replacing a traditional clinical study [21]. The emergence of such qualified virtual clinical trials represents a significant milestone in regulatory acceptance of in silico methods.

The International Medical Device Regulators Forum (IMDRF) continues working toward global harmonization of these approaches, though acceptance remains inconsistent across regulatory bodies [21]. While the FDA has made significant strides in accepting computational evidence, the EU MDR and EMA have not fully caught up to this level of acceptance, creating regulatory complexity for global device manufacturers. This evolving landscape underscores the importance of early regulatory engagement through Q-Sub meetings to establish the acceptability of proposed computational approaches, required validation evidence, and strategies for integrating with traditional testing methods [21].

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Multi-Scale Validation in Neurostimulation

Validation of neurostimulation models requires a multi-scale approach spanning from cellular responses to clinical outcomes. The following workflow illustrates a comprehensive validation framework for computational models in neurostimulation research:

Diagram 1: Model validation workflow

The validation workflow begins with computational model development, proceeds through verification and multiple validation stages, and culminates in regulatory-grade evidence generation. This systematic approach ensures models produce reliable predictions across biological scales.

Advanced research platforms enable rigorous validation through cloud-based workflows. For instance, the o²S²PARC and Sim4Life platforms allow researchers to create, execute, and automate computational pipelines that couple high-fidelity electromagnetic exposure modeling with neuronal dynamics [22]. These platforms facilitate validation through direct comparison between simulated neurostimulation effects and experimental measurements across spatial scales—from single-cell responses to brain network dynamics. Validation protocols typically include electromagnetic-neuro interactions across spatio-temporal scales covering the brain, spine, and peripheral nervous system [22].

Clinical Outcome Validation

For neurostimulation devices targeting chronic pain, validation against comprehensive clinical outcomes is essential. The Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT) criteria recommend a multidimensional assessment of chronic pain outcomes beyond simple pain intensity scores [23]. These criteria specify six core outcome domains that should be consistently reported: (1) pain intensity, (2) physical function, (3) emotional function, (4) participant ratings of improvement or satisfaction with treatment, (5) adverse events, and (6) participant disposition [23].

A systematic review of randomized clinical trials on neurostimulation for chronic pain revealed substantial variability in adherence to these complete outcome measures, with universal reporting of pain intensity but inconsistent assessment of other domains like emotional function and physical functioning [23]. This validation gap highlights the need for more comprehensive outcome reporting when validating computational models against clinical data. Models predicting neurostimulation efficacy should ideally output metrics across all IMMPACT domains to enable thorough validation against clinical trial results.

Comparative Analysis of Validation Methods

Cross-Technique Validation Approaches

Each validation approach offers distinct strengths and limitations for bridging in silico findings with real-world outcomes. The table below summarizes the primary validation methodologies employed across computational life sciences:

Table 1: Comparison of Validation Methods for In Silico Findings

| Validation Method | Key Applications | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Experimental Correlation [24] | Enzyme function studies; Cellular response prediction | Controlled conditions; Direct mechanistic insight; High-throughput capability | May not capture full biological complexity; Limited physiological context |

| In Vivo Experimental Correlation [20] | Whole-organism response; Systemic effects | Full physiological context; Clinical relevance | Ethical considerations; High cost; Complex interpretation |

| Retrospective Clinical Analysis [25] | Drug repurposing; Treatment outcome prediction | Real-world human data; Large sample potential | Confounding factors; Data quality variability |

| Literature Validation [25] | Hypothesis generation; Model benchmarking | Broad knowledge base; Rapid implementation | Inconsistent data quality; Reporting biases |

| Prospective Clinical Trial Correlation [23] | Medical device efficacy; Therapeutic optimization | Gold standard evidence; Controlled conditions | Resource intensive; Ethical considerations; Time constraints |

Validation in Drug Discovery and Development

In computational drug discovery and repurposing, validation strategies typically follow a structured pipeline. The rigorous drug repurposing pipeline involves making connections between existing drugs and diseases needing treatments based on features collected via biological experiments or clinical data [25]. After hypothesis generation through computational prediction, validation employs independent information not used in the prediction step, such as previous experimental/clinical studies or independent data resources about the drug-disease connection [25].

Studies with strong validation provide multiple forms of supporting evidence, often combining computational methods (retrospective clinical analysis, literature support, public database search) with non-computational methods (in vitro, in vivo experiments, clinical trials) [25]. This multi-modal validation approach reduces false positives and builds confidence in repurposed drug candidates. For example, a comprehensive review of computational drug repurposing found that only 129 out of 732 studies included both computational and experimental validation methods, highlighting the validation gap in current practice [25].

Case Studies: Validation Successes and Gaps

Medical Device Innovation

In silico trials have demonstrated particular success in medical device innovation, where computational models simulate device performance within virtual anatomical environments. Cardiovascular device developers now routinely use computational fluid dynamics models to simulate blood flow patterns around stents, predicting areas where restenosis might occur and optimizing strut geometry accordingly [21]. These simulations undergo rigorous validation through comparison with benchtop testing and clinical outcomes, creating validated predictive tools that can reduce the need for extensive physical prototyping.

In transcatheter aortic valve replacement, virtual testing helps predict paravalvular leak and optimal sizing across diverse patient anatomies [21]. Rather than relying solely on limited bench testing or small pilot studies, manufacturers can explore thousands of anatomical variations digitally, with validation against clinical performance data ensuring predictive accuracy. This approach enables both device optimization and personalized patient selection, with validation studies demonstrating improved clinical outcomes compared to traditional methods.

Limitations in Predictive Accuracy

Despite advances, significant validation gaps persist. A striking example comes from a study comparing in silico predictions with in vitro enzymatic assays for galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase (GALT) variants [24]. The research revealed significant discrepancies between computational predictions and experimentally measured enzyme activity. While in vitro assays showed statistically significant decreases in enzymatic activity for all tested variants of uncertain significance compared to native GALT, molecular dynamics simulations showed no significant differences in root-mean-square deviation data [24]. Furthermore, predictive programs like PredictSNP, EVE, ConSurf, and SIFT produced mixed results that were inconsistent with enzyme activity measurements [24].

This validation study highlights that even sophisticated in silico tools may not reliably predict biological function, particularly for missense mutations affecting protein activity. The authors concluded that the in silico tools used "may not be beneficial in determining the pathogenicity of GALT VUS" despite their widespread use for this purpose [24]. Such validation gaps emphasize the continued importance of experimental confirmation for computational predictions, especially in clinical decision-making contexts.

Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing robust validation protocols requires specialized computational and experimental resources. The table below outlines key research reagent solutions essential for validating in silico findings in neurostimulation and computational life science research:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Model Validation

| Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Validation Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| o²S²PARC Platform [22] | Cloud-native computational pipeline development | Build, share, reproduce complex modeling workflows from MRI to neuronal dynamics | Browser-based access; Pre-built computational workflows; High-fidelity EM modeling |

| Sim4Life [22] | Image-based, regulatory-grade simulations | Create anatomically detailed human body models with embedded nerve and brain networks | Multi-scale modeling; Coupled physical phenomena; Automated compliance checking |

| Modelscape Validate [26] | Model validation workflow management | Document validation protocols; Ensure traceability and reproducibility | Customizable templates; Automated documentation; Integration with development workflows |

| ASME V&V 40 Standard [21] | Credibility assessment framework | Structured approach to verification and validation for medical applications | Risk-informed validation planning; Context-of-use evaluation; Uncertainty quantification |

| IMMPACT Criteria [23] | Clinical outcome assessment | Multidimensional pain outcome measurement for neurostimulation trials | Six core domains; Patient-centered metrics; Regulatory recognition |

Validation Workflow Implementation

The following diagram illustrates the implementation of a comprehensive validation strategy integrating computational and experimental approaches:

Diagram 2: Integrated validation strategy

This integrated validation approach ensures computational models undergo rigorous testing across multiple evidence domains, strengthening the bridge between in silico predictions and real-world outcomes.

The critical role of validation in bridging in silico findings with real-world outcomes continues to evolve alongside computational methodologies. While significant progress has been made in establishing validation frameworks and regulatory pathways, the persistent gaps between computational predictions and experimental measurements highlight the need for continued validation science development. The integration of artificial intelligence with traditional physics-based models opens new possibilities through surrogate modeling, optimal configuration identification, and performance forecasting across diverse patient populations [21].

The future of computational life sciences undoubtedly includes expanded use of in silico methods, but their impact will be determined by the rigor of their validation. As regulatory agencies increasingly accept computational evidence, the establishment of model qualification databases as shared repositories of validated computational models will be essential [21]. By advancing validation science across multiple evidence domains—from molecular simulations to clinical outcomes—researchers can fully realize the potential of in silico methods to accelerate discovery, reduce costs, and improve patient outcomes across neurostimulation and biomedical research.

From Theory to Practice: Workflows for Building and Applying Validated Models

Validation is a critical component of research and development, ensuring that methodologies produce reliable, reproducible, and clinically meaningful results. This guide examines and compares the validation workflows from two distinct neurostimulation domains: Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) for neuropsychiatric disorders and Transcranial Electrical Stimulation (tES) for non-invasive brain modulation. While DBS involves invasive surgical implantation with intensive long-term clinical monitoring, tES utilizes non-invasive techniques requiring precise parameter reporting. By analyzing their structured approaches to equipment qualification, parameter control, and outcome validation, researchers can extract valuable frameworks applicable to computational model validation in neurostimulation research. The protocols from these fields demonstrate how rigorous, step-by-step validation processes bridge the gap between theoretical models and clinical applications, ultimately supporting the development of safer and more effective neurostimulation therapies [27] [28] [29].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) for Neuropsychiatric Disorders

DBS clinical trials for conditions like treatment-refractory major depressive disorder require multi-year relationships between participants and study staff, involving frequent interactions and high participant burden. The validation protocol emphasizes patient safety, ethical considerations, and methodological rigor throughout the therapeutic intervention [27].

Key Methodological Components:

- Multidisciplinary Team Structure: Trials are conducted by experienced multidisciplinary teams mandatory for ethical research, including stereotactic and functional neurosurgery, psychiatry, neurology, neuropsychology, neuroethics, clinical research coordinators, and neural signal processing experts [27].

- Stimulation Protocol: DBS involves surgical implantation of electrodes and an implantable pulse generator delivering therapeutic stimulation to targeted brain regions. Programming adjustments typically occur 3-11 times within the first six months post-surgery, with more frequent visits in research settings [27].

- Trial Design Considerations: Due to ethical constraints against sham surgeries, randomized controlled trials often use within-participant crossover designs (AB/BA) where each participant receives both active and sham stimulation. Protocols include explicit criteria for prematurely exiting sham conditions due to patient decompensation [27].

Table: DBS Clinical Trial Activities and Frequency

| Activity Type | Frequency | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical assessments | Weekly to monthly | Monitor psychiatric symptoms and side effects |

| DBS programming sessions | 3-11 times in first 6 months | Optimize stimulation parameters |

| Neuropsychological testing | Every 3-6 months | Assess cognitive changes |

| Neuroimaging (MRI/fMRI) | Pre-op and annually | Verify lead placement and brain changes |

| Adverse event monitoring | Continuous | Ensure participant safety |

Transcranial Electrical Stimulation (tES) Reporting Standards

The Report Approval for Transcranial Electrical Stimulation (RATES) checklist was developed through a Delphi consensus process involving 38 international experts across three rounds. This initiative identified 66 essential items categorized into five groups, with 26 deemed critical for reporting [28].

Development Methodology:

- Delphi Process: The three-round Delphi technique used interquartile deviation (>1.00), percentage of positive responses (>60%), and mean importance ratings (<3) to assess consensus and importance for each item [28].

- Systematic Review Foundation: A separate CoRE-tES initiative (Consolidated Guidelines for Reporting and Evaluation of studies using tES) begins with a systematic review of recent tES literature to assess methodological and reporting quality, informing preliminary checklist items [29].

Critical Reporting Domains: The RATES checklist categorizes essential reporting items into five domains: participants (12 items), stimulation device (9 items), electrodes (12 items), current (12 items), and procedure (25 items). Even slight variations in these parameters can notably change stimulation effects, including reversal of intended outcomes [28].

Comparative Analysis of Validation Approaches

Quantitative Data Comparison

Table: Performance Metrics Comparison Across Validation Types

| Validation Aspect | DBS Clinical Validation | tES Technical Validation | Pharmaceutical Equipment Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Timeframe | Months to years | Single sessions to weeks | Days to weeks |

| Primary Success Metrics | Clinical symptom reduction, functional improvement | Effect size, reproducibility | Accuracy, precision, repeatability |

| Parameter Controls | Electrode location, stimulation parameters | Electrode montage, current intensity, duration | Calibration, operational parameters |

| Acceptance Criteria | Statistical vs. clinical significance | Statistical significance, adherence to protocol | Predetermined acceptance criteria vs. URS |

| Key Challenges | Participant retention, placebo effects | Heterogeneity, blinding integrity | Impact assessment, avoiding over-qualification |

Workflow Visualization

DBS and tES Validation Workflows: This diagram illustrates the parallel yet distinct validation pathways for Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) and Transcranial Electrical Stimulation (tES) protocols, highlighting their unique methodological approaches while demonstrating convergent validation objectives.

Essential Research Toolkit

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Neurostimulation Validation

| Item/Category | Function in Validation | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| DBS Electrodes | Deliver targeted stimulation to deep brain structures | Directional DBS leads with multiple contacts |

| tES Devices | Generate controlled electrical currents for transcranial stimulation | tDCS, tACS, and tRNS stimulators with precision current control |

| Electrode Materials | Interface between device and biological tissue | Ag/AgCl electrodes, conductive gels for tES; Platinum-iridium for DBS |

| Computational Modeling Platforms | Simulate neurostimulation effects and optimize parameters | Closed-loop cardiovascular-neural models, electric field models |

| Clinical Assessment Tools | Quantify therapeutic outcomes and side effects | Standardized depression scales (MADRS, HAM-D), cognitive batteries |

| Neuroimaging | Verify placement and monitor neural effects | MRI for DBS lead localization, fMRI for network effects |

| Data Collection & Monitoring | Ensure protocol adherence and data integrity | Electronic clinical outcome assessments, remote symptom monitoring |

Discussion: Implications for Computational Model Validation

The validation workflows from DBS and tES protocols offer complementary frameworks for computational model validation in neurostimulation research. DBS emphasizes clinical integration and adaptive long-term validation, while tES focuses on parameter standardization and reporting transparency. Together, they provide a robust foundation for developing computational approaches that are both clinically relevant and methodologically rigorous [27] [28].

Recent advances in computational modeling, such as the closed-loop human cardiac-baroreflex system for optimizing neurostimulation therapy for atrial fibrillation, demonstrate how biological system simulations can predict intervention outcomes before clinical implementation. This model successfully identified the atrioventricular node as a promising neurostimulation target, showcasing how computational approaches can generate testable clinical hypotheses [13].

For researchers developing computational models for neurostimulation, integrating both DBS and tES validation principles creates a comprehensive framework:

- Structured Parameter Reporting adapted from RATES checklist ensures model inputs and assumptions are transparent and reproducible [28].

- Clinical Outcome Alignment from DBS protocols grounds models in patient-relevant endpoints rather than theoretical constructs [27].

- Iterative Validation Cycles mirroring DBS parameter optimization processes enable continuous model refinement based on emerging data [27] [13].

- Multidisciplinary Integration essential to both protocols ensures models incorporate diverse expertise from engineering, clinical medicine, and basic science [27] [13].

The step-by-step validation workflows from DBS and tES protocols provide invaluable roadmaps for establishing robust methodological standards in computational neurostimulation research. DBS protocols demonstrate the critical importance of long-term clinical integration, multidisciplinary teams, and adaptive parameter optimization, while tES standardization efforts highlight the necessity of comprehensive parameter reporting and consensus-driven methodological guidelines. By synthesizing the strengths of both approaches—clinical relevance from DBS and methodological transparency from tES—researchers can develop computational models and validation frameworks that accelerate the development of safer, more effective, and personalized neurostimulation therapies. As computational approaches increasingly inform clinical device development, these integrated validation principles will be essential for bridging the gap between theoretical models and real-world therapeutic applications.

The validation of computational models for neurostimulation protocols presents a significant challenge in modern neuroscience. The efficacy of such models hinges on their ability to predict neurological and behavioral outcomes accurately, a task that requires integrating diverse, high-dimensional data types. This guide objectively compares the performance of primary neuroimaging and biosensing modalities—Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS), and behavioral assessment—within the specific context of model validation. Individually, these techniques provide valuable but incomplete insights; functional connectivity (FC) derived from fMRI has emerged as a robust feature for predicting behaviors like cognition and age [30], while EIS offers a powerful, label-free method for detecting biochemical biomarkers [31] [32]. However, their integration offers a more comprehensive validation framework. We summarize experimental data into structured tables, detail key methodologies, and diagram workflows to provide researchers with a clear comparison of how these modalities can be synergistically combined to enhance the precision and reliability of neurostimulation models.

Performance Comparison of Multimodal Data

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Modalities for Model Validation

| Modality | Key Measured Features | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Primary Data Output | Performance in Behavior Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional MRI (fMRI) | Functional Connectivity (FC), Graph Power Spectral Density, Regional Activity [30] | High (mm) | Moderate (seconds) | Brain network maps and time-series data [30] [33] | FC is best for predicting cognition, age, and sex; Graph power spectral density is second best for cognition and age [30]. |

| Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) | Biomarker-receptor interaction (e.g., proteins, hormones) on electrode surface [31] [32] | N/A (Bulk measurement) | High (milliseconds to seconds) | Nyquist/Bode plots providing equivalent circuit parameters [32] [34] | Detects biomarkers for ocular/systemic diseases (e.g., Alzheimer's, cancer); high sensitivity for target analytes [31]. |

| Behavioral Outcomes | Cognitive scores, mental health summaries, processing speed, substance use [30] | N/A | Continuous to discrete | Quantitative scores and categorical classifications [30] | Serves as the ground-truth target for predictive modeling from neuroimaging and biomarker data [30] [35]. |

Table 2: Scaling Properties and Integration Potential

| Modality | Scaling with Sample Size | Scaling with Acquisition Time | Key Integration Challenge | Complementary Role in Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fMRI | Performance reserves for better-performing features (e.g., FC) in larger datasets [30]. | Important to balance scan time and sample size; longer times can improve signal [30]. | High dimensionality of data (e.g., 37,401 features from FC) requires robust machine learning [30]. | Provides macroscale network dynamics and correlates of consciousness and behavior [30] [33]. |

| EIS | Enables high-throughput, point-of-care screening when integrated into portable biosensors [31] [32]. | Provides rapid, real-time measurements on living systems with wearable technology [31]. | Translating biomarker concentration from tear fluid to functional brain state [31]. | Offers molecular-level, personalized biomarker data that can ground models in physiological states [31]. |

| Behavioral Outcomes | Larger samples improve statistical power and model generalizability [30] [35]. | Longitudinal assessment captures dynamic adaptations and long-term effects. | Subjectivity of some measures (e.g., pain ratings) requires objective correlates [8]. | Serves as the ultimate endpoint for validating the functional output of neurostimulation [8] [35]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Predicting Behavior from fMRI Features

This protocol is adapted from a large-scale study comparing fMRI features for brain-behavior prediction [30].

- Dataset & Preprocessing: The study utilized 979 subjects from the Human Connectome Project (HCP) Young Adult dataset. Structural T1 images were processed with Connectomemapper3 and parcellated using the Lausanne 2018 atlas (274 regions). Functional images were minimally preprocessed, followed by confound regression (motion parameters and derivatives), detrending, and high-pass filtering at 0.01 Hz. Time series were parcellated by averaging voxel signals within each atlas parcel [30].

- Feature Extraction: Nine feature subtypes were extracted from the preprocessed fMRI data. These included:

- Functional Connectivity (FC): The Pearson correlation coefficient between the time series of every pair of brain regions was calculated. The upper triangle of the resulting FC matrix was vectorized, yielding 37,401 features per subject [30].

- Region-wise features: Measures such as the mean and standard deviation of the BOLD signal, mean square successive difference (MSSD) for BOLD variability, and the fractional amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations (fALFF) [30].

- Graph Signal Processing (GSP) features: Metrics derived using the brain's structural connectivity, including the graph power spectral density and the structural decoupling index (SDI) [30].

- Prediction & Scaling Analysis: Behavioral targets (cognition, mental health, processing speed, substance use, age, and sex) were predicted from the features using machine learning models. The study systematically investigated how prediction performance scaled with different combinations of sample size and scan time [30].

Protocol 2: Impedimetric Detection of Biomarkers via EIS

This protocol outlines the use of EIS for detecting disease biomarkers, relevant for correlating physiological states with neurostimulation outcomes [31] [32].

- Biorecognition Element Immobilization: A biosensor is constructed by immobilizing a specific biorecognition element (e.g., an antibody, enzyme, or nucleic acid) onto the surface of a working electrode. This element is chosen for its selective interaction with the target biomarker [31] [32].

- Sample Collection and Application: In the context of neurological research, tear fluid is a promising source of biomarkers. It can be collected non-invasively using a glass microcapillary tube placed at the inferior temporal tear meniscus, minimizing stimulation of reflex tears. The collected sample is then applied to the biosensor surface [31].

- Impedance Measurement: An alternating current (AC) voltage signal, typically with a small amplitude (e.g., 5-10 mV), is applied across a range of frequencies (e.g., from 0.1 Hz to 100 kHz). The resulting current is measured, and the complex impedance (Z), comprising magnitude and phase shift, is calculated for each frequency [32] [34].

- Data Analysis & Equivalent Circuit Modelling: The impedance data is plotted on a Nyquist plot. An appropriate equivalent electrical circuit model (e.g., the Randles circuit) is fitted to the data. The change in a key parameter like the charge transfer resistance (Rct) before and after biomarker binding is used as the quantitative signal for biomarker detection [32] [34].

Protocol 3: Quantifying Consciousness State with Integration-Segregation Difference

This protocol uses fMRI to calculate a metric that can validate neurostimulation effects on brain state [33].

- Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: Subjects are scanned under different conditions (e.g., awake vs. anesthetized) using resting-state fMRI. Standard preprocessing steps are applied, including head motion correction, normalization, and band-pass filtering [33].

- Dynamic Functional Connectivity: The preprocessed fMRI time series is divided into sliding windows. For each window, a functional connectivity matrix is calculated, often using Pearson correlation between regional time series [33].

- Graph Theory Metrics: For each connectivity matrix, two key graph theory metrics are computed:

- Integration (Multi-level Efficiency): Measures how readily information can be exchanged across the entire brain network.

- Segregation (Multi-level Clustering Coefficient): Measures the degree to which brain nodes form tightly interconnected groups or modules [33].

- Calculate Integration-Segregation Difference (ISD): The ISD metric is computed for each time window as follows: ISD = Integration - Segregation. This metric has been shown to reliably index states of consciousness, with higher negative values indicating a more segregated (less conscious) state [33].

Workflow Visualization for Data Integration

The following diagrams illustrate the logical relationships and workflows for integrating multimodal data to validate computational models of neurostimulation.

Diagram 1: Multimodal validation workflow.

Diagram 2: fMRI brain state calculation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials for Featured Experiments

| Item | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| High-Density MRI Atlas (e.g., Lausanne 2018) | Provides a parcellation scheme to divide the brain into distinct regions for time-series extraction and network analysis [30]. | Standardizing feature extraction from fMRI data across subjects for brain-behavior prediction studies [30]. |

| Graph Signal Processing (GSP) Toolkit | A principled computational approach for extracting structure-informed functional features from neuroimaging data using the underlying structural connectivity network [30]. | Generating novel fMRI features beyond standard FC to predict behavioral variables like cognition [30]. |