Strategies to Mitigate Fibrosis and Enhance Longevity in Neural Electrode Interfaces

The long-term performance of implantable neural electrodes is critically limited by the foreign body reaction (FBR), a complex immune response that culminates in fibrotic tissue encapsulation.

Strategies to Mitigate Fibrosis and Enhance Longevity in Neural Electrode Interfaces

Abstract

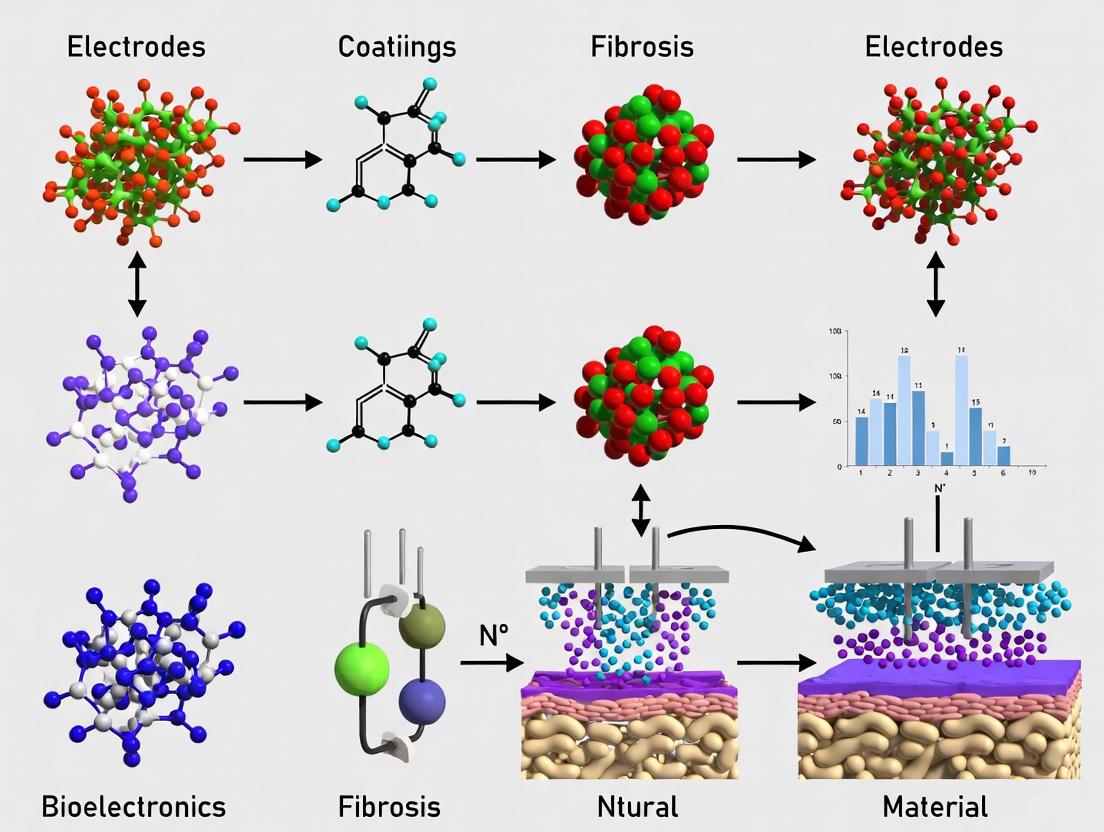

The long-term performance of implantable neural electrodes is critically limited by the foreign body reaction (FBR), a complex immune response that culminates in fibrotic tissue encapsulation. This fibrotic scar increases electrical impedance, attenuates signal quality, and ultimately leads to device failure. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the foundational biology of FBR, reviewing cutting-edge material science and bioengineering strategies to counteract it, examining troubleshooting for chronic stability, and validating approaches through in vitro and in vivo models. By synthesizing recent advances in biocompatible materials, drug-delivery coatings, and intelligent electrode design, this review outlines a pathway toward developing next-generation neural interfaces with improved functional longevity.

Understanding the Foreign Body Reaction: The Biological Basis of Fibrosis

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Our neural electrode recordings show a sharp increase in electrical impedance 2-3 weeks post-implantation. What is the likely cause and how can we confirm it?

A1: A sharp increase in impedance between weeks 2-4 is a classic symptom of progressing fibrous encapsulation [1] [2]. The foreign body reaction leads to the formation of a fibrotic capsule around the implant, which acts as an insulating layer [2]. To confirm:

- Histological Analysis: Explant the device and surrounding tissue for sectioning and staining. Look for the presence of a collagen-dense capsule, macrophages, and Foreign Body Giant Cells (FBGCs) at the tissue-device interface [1].

- Immunofluorescence: Stain for specific cell markers: CD68 (macrophages), α-SMA (myofibroblasts), and Collagen I/III (fibrotic capsule) [3].

Q2: We observe significant variability in fibrotic capsule thickness between our in-vivo models. What experimental factors should we standardize?

A2: Capsule thickness is highly sensitive to mechanical mismatch [3] [4]. Standardize these factors:

- Implant Stiffness (Young's Modulus): Ensure consistent material properties across implants. The goal is to match brain tissue (~1-10 kPa) [4].

- Implantation Method & Cross-sectional Area: The size and shape of the implant and the surgical technique (e.g., use of rigid shuttles) directly influence acute injury and chronic inflammation. Smaller, distributed implants cause less damage [4].

- Micromotion: Secure the device to minimize movement relative to the surrounding tissue, which exacerbates the chronic inflammatory response [4].

Q3: Which cytokines are the most critical biomarkers to monitor in the tissue surrounding the implant to track FBR progression?

A3: The FBR is driven by a cascade of cytokines. Key biomarkers to monitor include:

Table 1: Key Cytokines in the Foreign Body Reaction Cascade

| Cytokine/Chemokine | Primary Source | Primary Role in FBR |

|---|---|---|

| TGF-β | Platelets, Macrophages, FBGCs | Master regulator of fibrosis; stimulates fibroblast activation and ECM production [2] [3]. |

| CCL2 (MCP-1) | Macrophages | Key chemoattractant for recruiting monocytes/macrophages to the implant site [1] [2]. |

| IL-4 & IL-13 | Mast Cells, T-cells | Promote alternative (pro-healing) macrophage polarization and FBGC formation [1]. |

| PDGF | Platelets, Macrophages | Chemoattractant and mitogen for fibroblasts [1]. |

| TNF-α | Macrophages | Pro-inflammatory cytokine; amplifies early inflammatory response [1]. |

Q4: What are the most promising strategies to mitigate the Foreign Body Reaction for chronic neural implants?

A4: Strategies can be categorized as passive or active:

- Passive "Stealth" Strategies: Reduce the immune system's recognition of the implant. This includes using biomimetic coatings (e.g., hydrogels), optimizing device geometry to minimize cross-sectional area, and using flexible materials to reduce mechanical mismatch [2] [4].

- Active Modulation Strategies: Use the implant as a delivery vehicle to release anti-inflammatory agents (e.g., steroids like Dexamethasone) or factors that modulate the local immune environment (e.g., TGF-β inhibitors) directly to the tissue interface [4].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Inconsistent Macrophage Polarization In Vitro

- Issue: Difficulty in generating reproducible M1 (pro-inflammatory) and M2 (pro-healing) macrophage phenotypes for FBR studies.

- Solution:

- Protocol: Use primary bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) from consistent mouse strains for better reproducibility.

- Polarization Cocktails:

- Mechanical Cues: Culture cells on hydrogels with tunable stiffness (1-10 kPa for M2-like, >30 kPa for M1-like tendencies) to better mimic the in-vivo mechanical environment [3].

Problem: Excessive Fibrosis in Small Animal Models

- Issue: The fibrotic capsule is too thick, making it difficult to separate the device from the tissue for analysis.

- Solution:

- Optimize Implant Size: The implant's cross-sectional area should be minimized. For distributed filament electrodes, aim for widths of 10-50 μm [4].

- Pharmacological Inhibition: Consider systemic or local delivery of anti-fibrotic drugs (e.g., Losartan, an angiotensin inhibitor) to moderate the fibrotic response, but account for its broad effects in your experimental design.

- Perfusion Fixation: For histology, perform transcardial perfusion with paraformaldehyde (PFA) before explant to preserve tissue architecture and facilitate cleaner device removal.

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Histological Quantification of Fibrotic Capsule Thickness

Objective: To quantitatively assess the extent of fibrosis around an explanted neural device.

Materials:

- Ex-vivo tissue sample with implanted device

- 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA)

- Paraffin embedding station or Cryostat

- Microtome

- Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) stain, Masson's Trichrome stain

- Light microscope with digital camera and image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ)

Methodology:

- Fixation & Sectioning: Fix explanted tissue in 4% PFA for 24-48 hours. Decalcify if necessary. Embed in paraffin and section coronally at 5-10 μm thickness. Alternatively, for cryosectioning, embed in OCT compound after sucrose gradient dehydration.

- Staining:

- Perform H&E staining for general morphology and to identify the device-tissue interface.

- Perform Masson's Trichrome staining to specifically highlight collagen fibers (will appear blue).

- Imaging & Analysis:

- Image multiple, non-overlapping fields around the entire device circumference under 10x or 20x magnification.

- Using ImageJ, calibrate the scale. Draw perpendicular lines from the device surface to the outer edge of the dense, collagen-rich capsule. Measure the thickness at regular intervals (e.g., every 100 μm).

- Calculate the average capsule thickness and standard deviation for each sample.

Protocol 2: Immunofluorescence Analysis of FBR Cellular Components

Objective: To identify and localize key cellular players in the FBR.

Materials:

- Tissue sections on glass slides

- Antigen retrieval solution (e.g., citrate buffer)

- Blocking solution (e.g., 5% normal goat serum)

- Primary antibodies: α-SMA (myofibroblasts), CD68 (macrophages), Collagen I

- Fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies

- DAPI solution

- Fluorescent microscope or confocal microscope

Methodology:

- Deparaffinization & Antigen Retrieval: Deparaffinize and rehydrate sections. Perform heat-induced antigen retrieval in appropriate buffer.

- Staining:

- Block sections with 5% serum for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Incubate with primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C.

- Wash and incubate with secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature (protected from light).

- Counterstain nuclei with DAPI for 5 minutes.

- Imaging: Acquire z-stack images using a confocal microscope. Use consistent laser power and exposure settings across all samples for quantitative comparison.

Table 2: Temporal Progression of Key Events in the Foreign Body Reaction [1] [2]

| Time Post-Implantation | Phase | Key Cellular Events | Key Molecular Mediators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minutes - Hours | Protein Adsorption | Adsorption of fibrinogen, fibronectin, albumin, immunoglobulins to implant surface [1]. | Vroman Effect [1] |

| Hours - Days | Acute & Chronic Inflammation | Neutrophil infiltration, followed by monocyte recruitment and differentiation to macrophages [1]. | CCL2, CCL3, CCL5, TGF-β, PF4 [1] [2] |

| Days - Weeks | Foreign Body Reaction & Granulation Tissue | Macrophage fusion to form FBGCs; Fibroblast infiltration and neovascularization [1] [2]. | IL-4, IL-13, TGF-β, PDGF [1] |

| Weeks - Months | Fibrosis / Fibrous Encapsulation | Fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition; Massive deposition of Collagen I/III, forming an avascular capsule [2] [3]. | TGF-β, α-SMA, Connective Tissue Growth Factor (CCN2) [3] |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

FBR Signaling Pathway

Experimental Workflow for FBR Assessment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for FBR Investigation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Polyimide-based Neural Probes | Flexible substrate for neural implants; reduces mechanical mismatch with brain tissue (Young's modulus ~2-3 GPa) [4]. | Fabrication of chronic intracortical or intraneural electrodes for long-term FBR studies [4]. |

| PEG-based Hydrogels | Tunable, biomimetic coating for implants; can be functionalized with RGD peptides to improve biocompatibility [3]. | Creating a soft, hydrated interface layer on electrodes to dampen host immune recognition [2]. |

| TGF-β Neutralizing Antibody | Inhibits the TGF-β signaling pathway, the master regulator of fibrosis [3]. | Local delivery from an implant coating to assess the specific role of TGF-β in fibrous capsule formation in-vivo. |

| IL-4 & IL-13 Cytokines | Induce alternative (M2) macrophage polarization and promote FBGC formation in vitro [1] [3]. | Treatment of primary macrophages in culture to study the effects of M2 polarization on fibroblast activation in co-culture systems. |

| α-SMA, CD68, Collagen I Antibodies | Key markers for immunofluorescence: α-SMA (myofibroblasts), CD68 (macrophages), Collagen I (fibrosis) [3]. | Staining tissue sections to quantify the key cellular components of the FBR and correlate with impedance data. |

| Losartan | An angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) with known anti-fibrotic effects. | Administering systemically in animal models to investigate the potential reduction of FBR-related fibrosis around neural implants. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the key cellular players in the foreign body response (FBR) to implanted neural electrodes? The foreign body response is a coordinated process involving immune and stromal cells. The key players are:

- Macrophages: Myeloid immune cells that first respond to the implant. They orchestrate inflammation and can fuse to form Foreign Body Giant Cells (FBGCs) [5] [6].

- Foreign Body Giant Cells (FBGCs): Large, multinucleated cells formed by macrophage fusion. They persist at the biomaterial-tissue interface and contribute to chronic inflammation and degradation attempts [5] [6].

- Myofibroblasts: Activated fibroblasts that are the primary effector cells for fibrosis. They are characterized by excessive deposition of collagen and other extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, leading to the formation of a dense, scar-like capsule around the implant [5] [7] [8].

Why is the FBR a significant problem for neural electrodes? The FBR leads to the formation of a fibrotic scar and glial scar around the implant [9]. This has two major detrimental effects:

- Increased Electrode Impedance: The fibrotic tissue acts as an electrical insulator, reducing the signal quality recorded from or stimulated into neurons [9] [10].

- Neurodegeneration: The chronic inflammatory environment and physical encapsulation can lead to the loss of neurons near the electrode, further degrading interface performance [9] [10].

How do macrophages influence the development of fibrosis? Macrophages are central regulators. They exhibit plasticity and can adopt different functional phenotypes, often broadly categorized as:

- Pro-inflammatory (M1): Drive early inflammation and can recruit other immune cells and fibroblasts [5] [6].

- Pro-healing/Anti-inflammatory (M2): Promote tissue repair, but can also drive fibroblast activation and fibrosis [5] [6]. The persistence of macrophages and FBGCs at the implant site helps sustain a pro-fibrotic signaling environment, for instance, through the release of TGF-β1, a potent activator of myofibroblasts [5] [7].

What role does mechanical signaling play in the FBR? Recent research highlights that physical forces are a major driver of the FBR, independent of material chemistry [11] [12].

- Implant Stiffness: Stiffer implants generate greater mechanical stress at the tissue interface, which promotes FBGC formation and myofibroblast activation via mechanosensitive ion channels like TRPV4 [11].

- RAC2 Signaling: A 2023 study identified RAC2, a haematopoietic-specific GTPase, as a key mechanotransduction signal in myeloid cells (macrophages) that drives pathological FBR in humans. This pathway is activated by tissue-scale forces [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Excessive Fibrous Encapsulation of Implants

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Supporting Evidence | Recommended Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Chronic macrophage activation & FBGC formation | Macrophages and FBGCs secrete pro-fibrotic signals (e.g., TGF-β) that activate myofibroblasts [5] [6]. | 1. Target Macrophages: Use a CSF1R inhibitor (e.g., PLX5622) to deplete macrophages [10].2. Modulate Phenotype: Design biomaterials that promote a pro-regenerative macrophage phenotype [5]. |

| Persistent TGF-β1 / Smad signaling | TGF-β1 is the primary cytokine driving fibroblast-to-myofibroblast differentiation via the canonical Smad pathway [7] [8]. | 1. Local Drug Delivery: Use implants coated with or eluting TGF-β receptor inhibitors [7].2. Target Downstream Signaling: Investigate inhibitors of Smad3 or other non-canonical pathways (e.g., MAPK, ERK1/2) [7]. |

| Elevated mechanical forces at implant interface | Tissue-scale forces activate RAC2 in myeloid cells, driving severe FBR. Stiffness sensing via TRPV4 promotes FBGC formation and myofibroblast differentiation [11] [12]. | 1. Reduce Implant Stiffness: Use flexible, soft materials that better match brain tissue modulus [9] [12].2. Pharmacological Inhibition: Inhibit mechanosensing pathways (e.g., TRPV4 or RAC2 inhibitors) [11] [12]. |

Issue 2: Poor Long-term Signal Quality in Neural Recordings

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Supporting Evidence | Recommended Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Glial scarring and neuronal loss | The FBR creates an insulating glial/fibrotic capsule and a pro-inflammatory environment that is toxic to neurons [9] [10]. | 1. Minimize Insertion Trauma: Use ultra-thin, flexible electrodes and advanced insertion systems to reduce bleeding and initial tissue damage [9] [13].2. Anti-inflammatory Drugs: Administer local steroids (e.g., dexamethasone) to suppress the inflammatory response [10]. |

| Increased electrode impedance | Fibrotic tissue, composed of collagen and other ECM proteins deposited by myofibroblasts, electrically isolates the electrode [9] [10]. | 1. Reduce Cross-section: Use neural probes with a smaller footprint to displace less tissue and minimize the FBR target [9].2. Surface Modification: Develop non-fouling surface chemistries to reduce protein adsorption and subsequent cell adhesion [5] [9]. |

Table 1: Experimental Outcomes of Macrophage Depletion on Cochlear Implant FBR Data derived from a study using the CSF1R inhibitor PLX5622 in a mouse model [10].

| Parameter | Control Diet (No PLX) | PLX5622 Diet (Macrophage Depletion) | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Macrophage Infiltration | Present in implanted cochleae | Significantly reduced at all time points | Confirms efficacy of macrophage depletion strategy [10]. |

| Scala Tympani Fibrosis (α-SMA+ volume) | Evident | Not reduced | Suggests other cells or pathways can sustain fibrosis; macrophages may not be the sole driver in this context [10]. |

| Electrode Impedance | Baseline levels | Increased compared to controls | Macrophages may play a role in maintaining a conductive interface; their removal may be detrimental to signal conduction [10]. |

| Spiral Ganglion Neuron (SGN) Survival | Baseline survival | Decreased in implanted and contralateral cochleae | Highlights a critical role for macrophages in promoting neuronal survival post-implantation [10]. |

Table 2: Impact of Implant Physical Properties on the Foreign Body Response

| Property | Effect on FBR | Key Molecular Mediators | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stiffness | Stiffer implants promote FBGC formation, fibrosis, and pathological FBR. Softer, flexible implants reduce glial scarring. | TRPV4, RAC2, Cytoskeletal remodeling [11] [9] [12] | |

| Cross-sectional Size | Smaller probes displace less tissue, cause less vascular damage, and demonstrate improved integration with reduced gliosis. | N/A (Primarily a physical effect) [9] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Assessing the Role of Macrophages via Pharmacological Depletion

Objective: To determine the specific contribution of macrophages to the FBR and neural health around an implant.

Reagents:

- PLX-5622: A CSF1R inhibitor formulated into rodent chow at 1200 ppm [10].

- Control Diet: Standard AIN-76A chow.

- Animal Model: CX3CR1+/GFP reporter mice (to visualize macrophages) [10].

- Implants: Neural electrode or cochlear implant array.

Methodology:

- Pre-treatment: Begin feeding mice the PLX-5622 or control diet 7 days prior to implantation to achieve pre-depletion of macrophages [10].

- Surgical Implantation: Perform the implant surgery using aseptic techniques. Minimize insertion trauma and bleeding [9].

- Post-operative Monitoring: Continue the specialized diet for the duration of the study (e.g., 28-56 days). Monitor functional outcomes like electrode impedance and neural response thresholds [10].

- Tissue Collection & Histology: At endpoint, perfuse and harvest the implanted tissue.

- Fixation and Sectioning: Cryopreserve and section the tissue.

- Immunostaining:

- Image Analysis: Use software (e.g., IMARIS) to quantify:

Protocol B: Evaluating the Role of Mechanosensing via TRPV4 Inhibition

Objective: To investigate the contribution of stiffness-induced mechanosensing to FBGC formation and fibrosis.

Reagents:

- TRPV4 Inhibitor: e.g., GSK2193874.

- Animal Model: Wild-type and TRPV4-/- mice [11].

- Implants: Biomaterials of varying stiffness (e.g., soft vs. stiff silicone).

Methodology:

- In Vivo Implantation: Implant biomaterials subcutaneously or in the target neural tissue of wild-type mice treated with a TRPV4 inhibitor and TRPV4-/- mice [11].

- Tissue Analysis: Harvest implant capsules after a set period (e.g., 2-3 weeks).

- In Vitro Validation:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Investigating FBR

| Reagent | Function/Application | Example Use in FBR Research |

|---|---|---|

| PLX-5622 (CSF1R inhibitor) | Depletes macrophages and microglia by blocking a key survival signal. | Used to study the specific role of macrophages in FBR-driven fibrosis and neurodegeneration [10]. |

| Anti-α-SMA Antibody | Identifies activated myofibroblasts, the primary collagen-producing cells in fibrosis. | Critical for quantifying the extent of fibrotic encapsulation around implants via immunohistochemistry [7] [10]. |

| Recombinant TGF-β1 | The primary cytokine to induce fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition in vitro and in vivo. | Used to activate fibroblasts and study TGF-β signaling pathways in controlled experiments [7] [8]. |

| TRPV4 Inhibitors (e.g., GSK2193874) | Blocks the mechanosensitive ion channel TRPV4. | Used to dissect the role of stiffness-sensing in FBGC formation and fibrotic activation [11]. |

| CX3CR1+/GFP Mice | Reporter mouse model where macrophages and microglia express GFP. | Allows for in vivo tracking and quantification of macrophage infiltration and localization around implants [10]. |

Signaling Pathway Visualizations

Diagram Title: Foreign Body Response Timeline

Diagram Title: Mechanosensing in FBR

The formation of fibrotic tissue around implanted electrodes is a common biological response that significantly impacts the performance and longevity of neural interfaces, cochlear implants, and other neuroprosthetic devices. This foreign body reaction, characterized by the activation of immune cells such as microglia and astrocytes, leads to the deposition of extracellular matrix components that form a dense, insulating scar tissue around the implant [4]. This fibrotic capsule acts as a physical barrier, increasing the distance between the electrode and its target neural tissue, which in turn leads to increased electrode impedance and attenuated signal quality [14] [4]. Understanding this relationship is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals working to improve the functional longevity of neural interfaces.

The following table summarizes the key performance metrics affected by fibrotic tissue formation:

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics Affected by Fibrotic Tissue Formation

| Performance Metric | Impact of Fibrosis | Consequence for Research & Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Electrode Impedance | Increase due to insulating effect of fibrotic tissue [14] [4] | Reduced charge transfer efficiency, higher power requirements [4] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Decrease due to increased distance from signal source [4] | Compromised accuracy of neural signal detection and decoding |

| Stimulation Threshold | Increase due to physical barrier between electrode and neurons [4] | Requires higher stimulation energy, potentially causing tissue damage |

| Long-term Stability | Gradual degradation as fibrosis progresses over time [4] [15] | Limited chronic reliability of neural interfaces |

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing Fibrosis-Related Issues

Q1: How can I determine if increased impedance in my chronic experiment is caused by fibrosis?

A common challenge in long-term neural interface studies is differentiating between impedance increases caused by fibrotic encapsulation versus other factors like electrode material degradation or protein adsorption.

Diagnostic Protocol:

- Monitor Impedance Trends: Track impedance over time. A gradual, persistent increase that stabilizes after several weeks is indicative of fibrotic encapsulation, as opposed to a sudden spike which may suggest lead fracture or connector issues [15].

- Conformational Testing: For flexible electrodes, analyze the relationship between mechanical stress and impedance. Performance degradation that recovers after rest periods may indicate material fatigue rather than stable fibrosis [16].

- Post-mortem Histological Correlation: The most definitive method is to correlate terminal impedance measurements with post-mortem histology. Techniques like serial block-face imaging can precisely quantify the fibrotic tissue area and its spatial relationship to the electrode [14].

Interpretation of Results: It is critical to note that while impedance measurements can indicate the presence of an insulating layer, studies on pelvic nerve implants have shown that absolute impedance values may not correlate directly with the absolute amount of fibrotic tissue [14]. Therefore, impedance should be used as a relative indicator of interface changes rather than an absolute metric of fibrosis severity.

Q2: What are the primary failure modes observed in electrodes affected by fibrosis?

Fibrosis can lead to several distinct operational failures in neural recording and stimulation systems.

Table 2: Electrode Failure Modes Linked to Fibrosis

| Failure Mode | Description | Observable Symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Signal Attenuation | Reduced amplitude of recorded neural signals due to increased electrode-tissue distance [4]. | Gradual decrease in spike amplitude over weeks; increased difficulty in isolating single-unit activity. |

| Increased Stimulation Threshold | More energy required to activate neurons due to the insulating fibrotic capsule [4]. | Previously effective stimulation parameters no longer elicit a neural response; higher current/voltage needed. |

| Loss of High-Frequency Information | The fibrotic tissue acts as a low-pass filter, attenuating high-frequency signal components [4]. | Deterioration in the quality of high-frequency local field potentials (LFP) and spike waveforms. |

| Chronic Inflammatory Cycle | Ongoing micro-movements of the electrode can cause persistent inflammation, worsening fibrosis [4]. | Impedance continues to slowly increase over many months without stabilization. |

Q3: What strategies can mitigate the impact of fibrosis on electrode performance?

A multi-faceted approach is required to mitigate fibrosis, focusing on material design, surgical technique, and pharmacological intervention.

Material and Geometric Strategies:

- Flexible Substrates: Use electrodes with a low Young's modulus to reduce mechanical mismatch with soft neural tissue, thereby minimizing chronic inflammatory stimuli [17] [4].

- Miniaturization: Design smaller, filament-like electrodes to reduce the cross-sectional area of implantation and acute injury [4].

- Self-Healing Materials: Investigate novel conductive polymers and composites that can autonomously recover their electrical properties after mechanical damage, thus maintaining performance despite material fatigue in dynamic implant environments [16].

Pharmacological and Surface Modification Strategies:

- Drug-Eluting Systems: Develop controlled-release coatings that deliver anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., dexamethasone) locally to the implantation site to suppress the immune response [4] [15].

- Biocompatible Coatings: Apply surface modifications such as hydrophilic polymers or biomimetic peptides to make the electrode "invisible" to the immune system [4].

Diagram: The fibrosis cascade and mitigation strategies post-electrode implantation, showing the progression from acute inflammation to performance degradation and the points where different intervention strategies can be applied.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Fibrosis Assessment

Protocol 1: Longitudinal Impedance Monitoring in Chronic Models

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used in cochlear implant and peripheral nerve interface studies to track impedance as a proxy for tissue response [14] [15].

Objective: To characterize the dynamics of the tissue-electrode interface over time through frequent impedance measurements.

Materials:

- Custom Sound SQL database or equivalent for data management [18]

- MATLAB (R2023b or newer) for data processing scripts [18]

- Impedance measurement system (e.g., MAESTRO software for IFT or a custom neuroprosthetic system with telemetry) [15]

Procedure:

- Baseline Measurement: Record impedance values immediately after implantation and again at the initial activation/post-operative check (typically 2-4 weeks for neural interfaces) [18] [15].

- Frequent Sampling: For high temporal resolution, collect measurements twice daily (morning and evening) to capture diurnal fluctuations and the impact of electrical stimulation onset [15].

- Data Analysis: Calculate the mean impedance across all electrode channels. Analyze the trajectory over distinct post-operative phases:

- Correlation with Stimulation: Compare impedance trends between experimental groups with and without electrical stimulation to isolate its effect on the tissue response [15].

Protocol 2: Histological Correlation of Impedance and Fibrotic Tissue

This protocol is based on a study that directly correlated electrical measurements with in-situ imaging of the electrode-nerve interface [14].

Objective: To quantitatively assess the relationship between measured impedance/evoked potential thresholds and the physical properties of the fibrotic interface.

Materials:

- Chronic in vivo electrode array (e.g., extraneural four-platinum electrode array) [14]

- Serial block-face staining and imaging setup [14]

- Standard electrophysiology setup for measuring common ground impedance, transimpedance, and electrically evoked neural thresholds [14]

Procedure:

- Chronic Implantation: Implant the electrode array on the target nerve (e.g., rat pelvic nerve) for a defined period (e.g., two weeks) [14].

- Electrical Measurements: Periodically measure common ground impedance, transimpedance, and neural thresholds throughout the implantation period [14].

- In-situ Imaging: At the study endpoint, use a serial block-face staining and imaging technique to preserve the spatial relationship between the electrode and the tissue. This allows for precise measurement of the fibrotic tissue area and the distance from the electrode surface to the neural tissue [14].

- Statistical Analysis: Perform correlation analysis between the final electrical measurements (impedance and thresholds) and the quantified histological metrics (fibrotic area, nerve distance). Studies using this method have found that while impedance indicates the presence of interface tissue, it may not correlate with the absolute amount of fibrosis, highlighting the need for direct histological validation [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Investigating Electrode-Fibrosis Interactions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS Conductive Polymer | Coating to reduce electrode impedance and improve charge transfer efficiency [17]. | Enhances interface stability but long-term durability in vivo requires further investigation. |

| Self-Healing Polymers (SHP) | Substrate for creating neural interfaces that recover from mechanical fatigue [16]. | Critical for maintaining performance in dynamic implant environments; look for low Tg and high toughness. |

| Dexamethasone | Anti-inflammatory drug incorporated into drug-eluting coatings to suppress local immune response [15]. | Effective in reducing acute inflammation; optimal release kinetics for chronic applications is an active research area. |

| Poly(L-lactic acid)-poly(trimethylene carbonate) (PLLA-PTMC) | Biodegradable substrate for temporary neural interfaces [17]. | Eliminates need for explantation; degradation rate must match the period of intended use. |

| Silk Fibroin-based Nerve Conduits | Biocompatible, degradable scaffolds providing mechanical support and promoting nerve regeneration [17]. | Offers excellent biocompatibility and tunable degradation properties. |

| Ag nanowire/Ag flake composites | Conductive fillers in self-healing bilayer electrodes for recoverable electrical percolation pathways [16]. | Pt coating is often necessary to enhance biocompatibility and charge injection capacity. |

FAQs on Fibrosis and Electrode Performance

Q: Can the immune response in one implantation site affect a subsequent site in the same subject? A: Emerging evidence suggests yes. A retrospective study on sequential bilateral cochlear implants found that the second implanted ear exhibited a more rapid increase and greater magnitude of electrode impedance. This is consistent with a robust immune response in the second ear, potentially due to immunological memory or "contralateral priming" from the first implant [18].

Q: Are there new material technologies that actively combat performance degradation? A: Yes, cutting-edge research focuses on "performance-recoverable" systems. For example, self-healing, stretchable bilayer (SSB) electrodes have been developed that can spontaneously reconstruct their electrical percolation pathways after damage or fatigue, effectively recovering their electrical performance within seconds. This is a promising strategy to counteract the chronic degradation caused by the inflammatory environment [16].

Q: How does the mechanical property of an electrode influence fibrosis? A: The mechanical mismatch between a rigid electrode and soft neural tissue is a primary driver of chronic inflammation and fibrosis. Flexible electrodes with a low Young's modulus significantly reduce this mismatch, leading to less persistent glial scarring and better long-term signal stability. The shape and implantation method must be coordinated to minimize acute injury during insertion [4].

Q: Is impedance a reliable standalone metric for fibrosis in peripheral nerve interfaces? A: Caution is advised. A study on rat pelvic nerves found no significant correlation between impedance or neural threshold and the quantified area of fibrotic tissue. While impedance indicates interface changes, it should not be used as the sole metric for fibrosis severity. Combining electrical measurements with histological validation is considered best practice [14].

Troubleshooting Guide: Chronic Inflammation and Electrode Failure

Q1: Why does a glial scar form around my implanted neural electrode, leading to signal degradation? The formation of a glial scar, or glial encapsulation, is a direct consequence of the chronic foreign body response triggered by the mechanical mismatch between the implanted electrode and the surrounding brain tissue [19]. Brain tissue is exceptionally soft, with a Young's modulus of approximately 1–10 kPa [4] [20]. When a rigid electrode (e.g., silicon at ~102 GPa or platinum at ~102 MPa) is implanted, this stiffness mismatch causes ongoing micro-movements and friction against the soft neural tissue [4]. This persistent mechanical irritation activates microglia and astrocytes. Activated microglia adopt an amoeboid shape, proliferate, and release pro-inflammatory cytokines and cytotoxic factors [19]. Astrocytes become reactive, undergo hypertrophy, and upregulate Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP), secreting extracellular matrix components that eventually form a dense, insulating physical barrier around the electrode [19] [4]. This scar tissue increases the distance between neurons and the electrode's recording sites, causing a rapid attenuation of neural signals and a sharp rise in impedance, ultimately leading to electrode failure [4].

Q2: What are the key cellular events following electrode implantation that lead to chronic inflammation? The tissue response unfolds over acute and chronic timescales [19]:

- Initial Injury and Acute Response (First 24-48 hours): Electrode insertion severs blood vessels, tears the extracellular matrix, and ruptures neural cell bodies and processes. This leads to bleeding, serum protein leakage, and the infiltration of blood-borne immune cells. Microglia are activated within hours, sending projections toward the injury site and migrating to surround the implant within 24 hours [19].

- Chronic Response (Weeks to Months): The sustained mechanical mismatch prevents the resolution of inflammation. Microglia remain activated, and astrocytes continue to proliferate and deposit extracellular matrix. The result is the formation of a persistent glial scar, which isolates the electrode from the functional neural tissue [19] [20].

Q3: My flexible electrode still triggers an immune response. Why? While flexible electrodes with a lower Young's modulus significantly reduce mechanical mismatch compared to rigid devices, they are not entirely invisible to the immune system [4]. The implantation method itself is a key factor. Flexible electrodes often require rigid shuttles for insertion, which temporarily recreate the problem of a stiff device penetrating the brain, causing acute injury [4]. Furthermore, the geometric design of the electrode (e.g., its cross-sectional area and shape) continues to influence the extent of chronic inflammation. Even a flexible electrode with a large cross-section can cause significant tissue displacement and sustain a chronic inflammatory response due to macroscopic movements against the tissue [4].

Q4: How can I measure the success of my strategy to reduce fibrosis? Success can be evaluated through a combination of histological, functional, and electrochemical assessments, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Metrics for Assessing Reduced Fibrosis and Improved Biocompatibility

| Assessment Category | Specific Metric | Methodology/Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Histological Analysis | Microglial Activation | Immunohistochemical staining for markers like ED1; quantify cell density and morphology around the implant [19]. |

| Astrocytic Scarring | Immunohistochemical staining for GFAP; measure the thickness and density of the GFAP-positive barrier [19]. | |

| Neuronal Survival | Staining for neuronal markers (e.g., NeuN); quantify neuronal density in the vicinity of the electrode [19]. | |

| Functional Performance | Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Record neural signals over time; a stable or increasing SNR indicates healthy interface stability [20]. |

| Electrode Impedance | Measure impedance at 1 kHz; a stable, low impedance suggests minimal scar tissue formation [19]. | |

| Recording Longevity | Stable Single-Unit Yield | Track the number of distinct, isolatable neurons over weeks or months; extended longevity indicates reduced inflammatory encapsulation [4]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Investigations

Protocol 1: Assessing the Acute and Chronic Tissue Response to Implanted Electrodes

- Objective: To characterize the timeline of glial activation and scar formation around an electrode with different stiffness profiles.

- Materials: Electrodes (rigid vs. flexible), animal model (e.g., rat or mouse), stereotaxic surgical setup, perfusion and fixation equipment, cryostat, antibodies (e.g., anti-Iba1 for microglia, anti-GFAP for astrocytes, anti-NeuN for neurons).

- Methodology:

- Implantation: Surgically implant the test electrodes into the target brain region(s) using aseptic techniques.

- Time-Point Sacrifice: Euthanize animals and perform transcardial perfusion with paraformaldehyde at predetermined time points (e.g., 24 hours, 1 week, 4 weeks, 8 weeks post-implantation).

- Tissue Processing: Extract brains, post-fix, cryoprotect, and section tissue into slices containing the electrode track.

- Immunohistochemistry: Label tissue sections with fluorescent antibodies against Iba1, GFAP, and NeuN.

- Imaging and Quantification: Use confocal or fluorescence microscopy to image the tissue surrounding the implant. Quantify metrics such as microglial density, astrocytic scar thickness, and neuronal density within defined radii from the electrode track [19].

Protocol 2: Evaluating Electrode Performance via Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

- Objective: To monitor the functional integrity of the electrode-tissue interface and infer scar formation.

- Materials: Implanted electrode, potentiostat/impedance analyzer, reference electrode, counter electrode.

- Methodology:

- Baseline Measurement: Perform EIS on the electrode in saline prior to implantation to establish a baseline.

- In Vivo Tracking: At regular intervals post-implantation, connect the implanted electrode to the analyzer and record the impedance spectrum, typically from 1 Hz to 100 kHz.

- Data Analysis: Focus on the impedance magnitude at 1 kHz, which is strongly influenced by the biological environment. A steady increase over time is indicative of insulating scar tissue forming around the electrode [19] [21].

Signaling Pathways in the Foreign Body Response

The following diagram illustrates the key cellular and molecular events triggered by electrode implantation.

Strategies for Mitigating Mechanical Mismatch

The diagram below outlines a strategic workflow for developing neural interfaces that minimize the foreign body response.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Neural Interface Biocompatibility Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Flexible Polymer Substrates (e.g., Polyimide, Parylene C) | Serves as the base material for electrodes, providing a low Young's modulus that better matches brain tissue (1-10 kPa) [4] [20]. | Reduces chronic mechanical mismatch and micromotion-induced damage. |

| Conductive Coatings (e.g., PEDOT:PSS, Carbon Nanotubes) | Coated on electrode sites to improve charge transfer capacity and lower interfacial impedance, enhancing signal quality [20]. | Can improve the efficiency of stimulation and the signal-to-noise ratio of recordings. |

| Bio-Dissolvable Stiffeners (e.g., Polyethylene Glycol - PEG) | Temporarily increases the stiffness of a flexible electrode to enable penetration; dissolves post-implantation to restore flexibility [4]. | Mitigates acute implantation injury caused by rigid shuttles. |

| Anti-inflammatory Agents (e.g., Dexamethasone) | Incorporated into electrode coatings for controlled release to locally suppress the immune response post-implantation [4]. | Actively modulates the inflammatory environment to reduce glial activation. |

| Immunohistochemistry Antibodies (anti-Iba1, anti-GFAP, anti-NeuN) | Used to label and quantify microglia, astrocytes, and neurons in tissue sections for post-mortem analysis of the tissue response [19]. | Critical for validating the efficacy of any new electrode design or anti-fibrosis strategy. |

Innovative Material and Bioengineering Solutions for Anti-Fibrotic Interfaces

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting and FAQs

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and frequently asked questions (FAQs) for researchers working with Polyimide, Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), and Polylactic acid (PLA) in the context of developing neural electrodes with reduced fibrotic response. The content is framed within a broader thesis on reducing fibrosis around neural implants.

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Problem: Excessive Fibrosis and Glial Scarring Around Implant

- Symptoms: Gradual degradation of neural signal quality (increased impedance, signal attenuation) over weeks to months post-implantation [4].

- Potential Causes:

- Solutions:

- Optimize mechanical properties: Blend rigid polymers like PLA with softer polymers (e.g., PCL) or design flexible, thin-film electrodes to lower the bending stiffness and better match neural tissue [22] [4].

- Apply surface modifications: Functionalize the electrode surface with bioactive coatings (e.g., PEG, laminin) or drug-eluting systems to actively suppress the immune response and promote integration [22] [4].

Problem: Uncontrolled or Unexpected Polymer Degradation

- Symptoms: Premature loss of mechanical integrity, altered surface morphology, and unexpected local tissue reactions.

- Potential Causes:

- Solutions:

- Control environmental factors: During in vitro testing, precisely control the temperature and pH of the immersion solution. A temperature increase of 50°C can accelerate PLA hydrolysis by 30-50% [22].

- Modify polymer chemistry: Copolymerize with more hydrophobic monomers or adjust crystallinity to slow down hydrolysis rates.

Problem: Poor Cell Adhesion or Cytotoxicity on Polymer Surface

- Symptoms: Low cell viability in in vitro assays, poor integration with host tissue in vivo.

- Potential Causes:

- Solutions:

- Perform rigorous extraction cytotoxicity testing: Follow ISO 10993-5 guidelines, using methods like MTT assay to ensure cell viability is typically above 70% for device extracts [23].

- Enhance bioactivity: Modify the surface with extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins (e.g., collagen, laminin) or arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD) peptides to promote cell attachment [22].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key regulatory standards for biocompatibility testing of implantable neural devices? A1: The ISO 10993 series is the internationally recognized standard for the biological evaluation of medical devices [24]. Key parts for neural implants include:

- ISO 10993-1: Provides the overall framework for evaluation within a risk management process.

- ISO 10993-5: Specifies tests for in vitro cytotoxicity, a fundamental requirement for all devices [23] [24].

- ISO 10993-6: Evaluates local effects after implantation, which is critical for assessing fibrosis and tissue integration [25].

- ISO 10993-10: Covers tests for skin sensitization and irritation [24]. Always consult regional regulatory bodies like the FDA or EMA, as they provide specific guidances that align with, but may not fully recognize, all ISO standards [26] [23].

Q2: How does the "Big Three" in biocompatibility testing apply to my neural electrode made of Polyimide? A2: The "Big Three" tests—cytotoxicity, irritation, and sensitization—are required for almost all medical devices, including your Polyimide electrode [23].

- Cytotoxicity: Assesses if leachables from the Polyimide device kill cultured cells (e.g., L929 fibroblasts). This is a first-line screening test [23].

- Irritation: Evaluates the potential for the device to cause localized inflammation, which directly relates to the fibrotic response you aim to minimize.

- Sensitization: Determines if the device materials can cause an allergic reaction. These tests are typically performed on extracts of your device and are a mandatory part of the safety profile for regulatory submissions [23].

Q3: Beyond the "Big Three," what other biocompatibility tests are critical for chronic neural implants? A3: For long-term implants, additional evaluations are essential:

- Implantation Study (ISO 10993-6): This is crucial. It involves histopathological examination of the tissue surrounding the implant to quantify the immune response, fibrosis (collagen deposition), and tissue integration [25].

- Genotoxicity (ISO 10993-3): Ensures materials do not cause genetic damage.

- Systemic Toxicity (ISO 10993-11): Assesses potential effects on distant organs.

- Hemocompatibility (ISO 10993-4): Required if the device has contact with blood [24].

The following tables summarize key properties and experimental data for the polymers in the context of neural interfaces.

Table 1: Key Properties of Polyimide, PDMS, and PLA for Neural Interfaces

| Property | Polyimide | PDMS | PLA | Relevance to Neural Interfaces |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young's Modulus | ~2-8 GPa [4] | ~0.36-3 MPa [4] | ~1.5-3.5 GPa [22] | PDMS is closer to brain tissue (~1-10 kPa), reducing mechanical mismatch [20]. |

| Biodegradability | Non-degradable | Non-degradable | Degradable (hydrolytic/enzymatic) [22] | PLA is suitable for temporary implants; degradation rate must be controlled. |

| Key Biocompatibility Advantage | Excellent electrical insulation, high strength | High flexibility, low stiffness, gas permeable | Biocompatible, tunable degradation | PDMS minimizes chronic inflammation; PLA resorbs, avoiding a second surgery. |

| Key Biocompatibility Challenge | Can be stiff, leading to mechanical mismatch | Hydrophobic, can adsorb proteins, potential for encapsulation | Acidic degradation products may cause inflammation [22] | Surface modification is often required for PDMS and PLA to improve bio-inertness or buffer pH. |

Table 2: Summary of Key Biocompatibility Tests Based on ISO 10993

| Test Endpoint | Standard | Typical Method | Application to Neural Electrodes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytotoxicity | ISO 10993-5 [23] [24] | MTT/XTT assay on device extracts using L929 or Balb 3T3 cells [23] | First-line screening for leachable substances; >70% cell viability is a positive indicator [23]. |

| Sensitization | ISO 10993-10 [24] | Guinea Pig Maximization Test (in vivo) or in vitro alternatives | Assesses risk of allergic contact dermatitis from device materials. |

| Irritation | ISO 10993-10, -23 [24] | Skin irritation test (in vivo or in vitro models) | Evaluates potential for localized inflammatory response. |

| Implantation | ISO 10993-6 [25] | Histopathology of implanted site (H&E, Masson's Trichrome staining) [25] | Critical test for fibrosis; quantifies inflammation, collagen deposition, and tissue integration. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Vitro Cytotoxicity Testing by Extraction (Based on ISO 10993-5)

- Objective: To determine if leachables from the polymer sample are cytotoxic.

- Materials: Polymer samples (Polyimide, PDMS, PLA), cell culture medium (extraction vehicle), L929 fibroblast cells, 96-well cell culture plates, MTT reagent, incubator.

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Sterilize the polymer samples and immerse in culture medium at a surface area-to-volume ratio of 3 cm²/mL or 6 cm²/mL. Incubate at 37°C for 24 hours to create the extract [23].

- Cell Seeding: Seed L929 cells in a 96-well plate and culture until near-confluent.

- Exposure: Replace the culture medium in the wells with the polymer extract. Include a negative control (medium only) and a positive control (e.g., latex extract).

- Incubation: Incubate the cells with the extract for 24 hours at 37°C.

- Viability Assessment: Add MTT reagent to the wells. Living cells will convert MTT to purple formazan crystals. After solubilizing the crystals, measure the absorbance at 570 nm.

- Analysis: Calculate cell viability as a percentage of the negative control. A reduction in cell viability by more than 30% (i.e., viability below 70%) may indicate cytotoxicity [23].

Protocol 2: Histopathological Evaluation of Tissue Response Post-Implantation (Based on ISO 10993-6)

- Objective: To qualitatively and quantitatively assess the foreign body response, including fibrosis, to the implanted polymer in vivo.

- Materials: Polymer implants, animal model (e.g., rat), fixation buffer (e.g., formalin), paraffin or resin, microtome, staining solutions (H&E, Masson's Trichrome).

- Procedure:

- Implantation: Aseptically implant the polymer sample into the target tissue (e.g., brain, muscle) for a defined period (e.g., 4, 12, 26 weeks).

- Tissue Harvesting and Fixation: At the endpoint, carefully excise the implant with the surrounding tissue and fix in formalin to preserve tissue architecture [25].

- Processing and Sectioning: Dehydrate the tissue, embed it in paraffin or resin, and section it into thin slices (3-7 µm) using a microtome. Specialized laser microtomes (e.g., Tissue Surgeon) can be used for hard polymer-tissue composites [25].

- Staining:

- Analysis and Scoring: A board-certified pathologist examines the slides semi-quantitatively. Key parameters are scored:

- Inflammation: Number and distribution of lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages, and giant cells.

- Fibrosis: Thickness and density of the collagen capsule around the implant.

- Necrosis: Presence of dead tissue cells.

- Advanced Analysis: Digital pathology and AI-driven histomorphometry (e.g., with Visiopharm software) can be used for precise quantification of tissue density, cell counts, and capsule thickness [25].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Biocompatibility and Fibrosis Research

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| L929 Fibroblast Cells | A standard cell line for in vitro cytotoxicity testing [23]. | Screening polymer extracts for cytotoxic leachables. |

| MTT/XTT Assay Kits | Colorimetric assays to measure cell metabolic activity and viability [23]. | Quantifying cytotoxicity in accordance with ISO 10993-5. |

| Anti-PEG Antibodies | Research tool to study immune responses to PEGylated surfaces [22]. | Investigating pre-existing or induced immunity to a common coating polymer. |

| Masson's Trichrome Stain | Histological stain that differentiates collagen (blue/green) from muscle and cytoplasm (red) [25]. | Visualizing and quantifying fibrotic capsule formation around explanted devices. |

| Visiopharm Software | AI-driven digital pathology image analysis platform [25]. | Performing precise, reproducible histomorphometry on tissue sections. |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for evaluating a new polymer for a neural interface, from initial concept to advanced in vivo analysis.

Polymer Evaluation Workflow for Neural Interfaces

The diagram below outlines the key biological signaling pathways activated upon implantation of a neural electrode, leading to the critical outcome of fibrosis.

Fibrosis Pathway and Mitigation Strategies

This technical support guide provides troubleshooting and methodological assistance for researchers developing conductive, flexible composites based on PEDOT:PSS and nanomaterial hybrids. The content is specifically framed within a thesis research context aimed at reducing fibrosis around neural electrodes. The mechanical mismatch between rigid conventional electrodes and soft neural tissue (Young's modulus of 1–10 kPa) is a primary driver of the foreign body response, leading to glial scar formation and signal degradation [27] [20]. The strategies discussed herein focus on creating soft, compliant interfaces to mitigate this response.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

PEDOT:PSS Formulation and Processing

Q1: My pristine PEDOT:PSS film has low conductivity (<1 S/cm). How can I enhance it effectively?

- A: Low conductivity of pristine PEDOT:PSS is a common issue due to the insulating PSS shells surrounding conductive PEDOT cores [28]. The following strategies can yield significant improvements:

Table 1: Conductivity Enhancement Strategies for PEDOT:PSS

| Method | Mechanism | Typical Conductivity Achieved | Considerations for Neural Interfaces |

|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary Dopants (e.g., DMSO, EG) | Screen electrostatic attraction between PEDOT and PSS, facilitating charge hopping [29] [28]. | 10 - 1000 S/cm | Improves performance without introducing non-biocompatible nanoparticles. |

| Nanomaterial Blending (e.g., Graphene, Ag NPs) | Bridges PEDOT islands, creating additional conductive pathways [30] [28]. | Can exceed 1000 S/cm [28] | Biocompatibility check is critical. Silver nanoparticles may offer antimicrobial properties. |

| Multiple Deposition | Increases the concentration of PEDOT grains and improves film connectivity [28]. | Increases exponentially with layer number [28] | Increases film thickness, which may affect flexibility. |

| Acid Treatment (e.g., H₂SO₄) | Removes excess PSS and reorders PEDOT crystallites [29]. | Up to 4380 S/cm [29] | Harsh processing may not be suitable for all substrates; requires careful rinsing. |

Q2: My PEDOT:PSS film does not adhere well to the substrate (e.g., flexible Mylar or Si wafer). What is the solution?

- A: Poor adhesion is often due to contamination or insufficient surface energy. Implement a rigorous substrate cleaning and activation protocol [28]:

- Cleaning: Sonicate substrates in acetone for 10 minutes, followed by isopropyl alcohol (IPA) for another 10 minutes.

- Rinsing and Drying: Rinse with deionized (DI) water and blow-dry with nitrogen.

- Dehydration: Place substrates on a pre-heated hot plate at 110°C for 1-2 minutes.

- Surface Activation: Treat the cleaned substrate with oxygen plasma. This step is crucial for ensuring uniform coverage and strong adhesion for subsequent spin-coating [28].

Q3: How can I pattern PEDOT:PSS for creating microelectrodes?

- A: Standard photolithography can chemically deteriorate PEDOT:PSS. A reliable method uses a sacrificial metal layer [28]:

- Deposit a thin sacrificial metal layer (e.g., Silver) on the PEDOT:PSS film.

- Deposit and pattern a photoresist on top of the silver layer using standard lithography.

- Etch the exposed silver using a suitable etchant (e.g., nitric acid), which selectively removes the silver without damaging the underlying PEDOT:PSS.

- Etch the now-exposed PEDOT:PSS segments using oxygen plasma.

- Strip the remaining photoresist and etch the remnant silver islands, leaving behind the patterned PEDOT:PSS.

Mechanical and Biocompatibility Issues

Q4: The composite is too brittle and cracks under strain. How can I improve its stretchability?

- A: Pristine PEDOT:PSS films are flexible but only stretchable to ~10% [29]. To enhance stretchability for applications requiring tissue conformability:

- Blend with Elastomers/Plasticizers: Incorporate soft polymers (e.g., polyethylene oxide - PEO) or plasticizers to increase the elastic compliance of the composite [29] [30].

- Form Fibers or Gels: Processing PEDOT:PSS into hydrogel matrices or fibers can significantly enhance deformability and mimic the mechanical properties of neural tissue [29] [27].

- Deposit on Pre-strained Elastomers: Transfer the conductive film to a pre-stretched elastomer like PDMS. Upon release, the film forms wavy, buckled structures that can accommodate large tensile strains [29].

Q5: How can I assess the mechanical mismatch between my composite and neural tissue?

- A: The key parameter is the Young's (Elastic) Modulus. Neural tissue has a soft consistency, with a Young's modulus ranging from 1 to 10 kPa [20] [27]. Your composite should aim to be in this range. Nanoindentation or tensile testing can be used to characterize the modulus of your film. A significant mismatch with traditional materials like silicon (~180 GPa) or platinum (~170 GPa) contributes to chronic inflammation and scar tissue formation [27] [20].

Experimental Protocols for Key Experiments

Protocol: Formulating and Screen-Printing a PEDOT:PSS/Graphene Composite Ink

This protocol is adapted for creating flexible, conductive patterns on various substrates [30].

Objective: To prepare a stable, printable ink that exhibits enhanced electrical conductivity and excellent flexibility for deformable electronic devices.

Materials:

- PEDOT:PSS aqueous dispersion (e.g., Clevios PH1000)

- Graphene powder or solution

- Polyethylene Oxide (PEO) - as a viscosity modifier

- Deionized (DI) Water

- Screen printer and appropriate mesh screens

- Target substrate (e.g., oxygen plasma-treated Mylar)

Method:

- Ink Synthesis: Mix PEDOT:PSS dispersion with graphene powder at a predetermined weight ratio. Sonication or vigorous stirring is required to achieve a homogeneous dispersion.

- Viscosity Adjustment: Add PEO incrementally to the composite mixture. The ratio of PEO is critical to adjust the ink's viscosity and flowability without compromising electrical properties. A trade-off exists between ink printability, resolution, and electrical performance.

- Printing: Use the synthesized ink for screen printing onto the activated substrate. Optimize printing parameters (squeegee pressure, speed) for pattern resolution.

- Curing: Allow the printed patterns to dry and cure, typically at mild temperatures (e.g., 60-90°C) to evaporate solvents and set the film.

Troubleshooting: If the printed circuit cracks, reduce the graphene content or increase the PEO plasticizer. If the pattern resolution is poor, increase the PEO content to increase viscosity or optimize screen mesh size.

Protocol: Enhancing Biocompatibility and Reducing Fibrosis via Surface Biofunctionalization

Objective: To create a "bioactive" neural interface that minimizes the foreign body response (FBR) and glial scar formation.

Materials:

- Fabricated soft electrode (e.g., PEDOT:PSS-based composite)

- Relevant biomolecules (e.g., Laminin, Fibronectin, anti-inflammatory drugs like Dexamethasone)

- Hydrogel matrix (e.g., GelMA, agarose)

- Standard cell culture or sterile handling equipment

Method:

- Surface Coating: Physically adsorb or chemically tether biomolecules to the electrode surface. These can be peptides derived from extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins (e.g., Laminin) to promote neuronal attachment over glial cells.

- Hydrogel Encapsulation: Encapsulate the soft electrode within a hydrogel layer. Hydrogels closely match the mechanical properties of brain tissue and can be loaded with anti-inflammatory drugs for localized, sustained release to suppress the initial immune response [27].

- In-Vitro Validation: Culture the functionalized electrodes with a mixed cell population (e.g., neurons and astrocytes) to assess selective neuronal adhesion and reduced astrocytic activation.

Troubleshooting: If the coating delaminates, use stronger covalent bonding strategies (e.g., silane chemistry). If the drug releases too quickly, adjust the hydrogel cross-linking density.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Materials for Developing Low-Fibrosis Neural Electrodes

| Item | Function in Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS Dispersion | The primary conductive polymer; provides the foundation for the flexible, organic electrode [29] [28]. | Commercial sources (e.g., Clevios) vary; conductivity can be enhanced with secondary dopants. |

| Graphene / Carbon Nanotubes | Nanomaterial additives to significantly enhance the electrical conductivity and mechanical robustness of the composite [30] [27]. | Functionalization may be needed for stable dispersion in polymer matrix. |

| PDMS / Soft Elastomers | Used as flexible substrates or encapsulation layers to achieve a low elastic modulus matching neural tissue [27]. | Surface activation (e.g., oxygen plasma) is required for adhesion. |

| Polyethylene Oxide (PEO) | A polymer additive that acts as a plasticizer to improve ink printability and composite stretchability [30]. | Ratio must be optimized for a trade-off between mechanical and electrical properties. |

| Oxygen Plasma System | Critical for cleaning and activating substrate surfaces to ensure strong adhesion of PEDOT:PSS films [28]. | Standard equipment in cleanroom or microfluidic fabrication labs. |

| Laminin / Fibronectin | ECM-derived proteins for bioactive surface functionalization to promote neuronal integration and reduce glial scarring [27]. | Requires sterile handling and specific buffer conditions for coating. |

| Biocompatible Hydrogels | Used to create a soft, hydrated interface between the electrode and tissue, mitigating FBR [27]. | Choice of hydrogel (e.g., GelMA, agarose) influences drug release and cell interaction. |

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates a recommended experimental workflow for developing and characterizing these composites, from material synthesis to in-vitro biocompatibility validation.

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Neural Electrode Development

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges in Reducing Fibrosis

FAQ 1: Why is there a progressive decline in the signal-to-noise ratio of my neural recordings over several weeks? This is a classic sign of the foreign body response (FBR), where the body recognizes the implant as a foreign object [27]. The process begins with protein adsorption and leads to the activation of microglia and astrocytes, resulting in the formation of a protective glial scar and fibrotic tissue around the electrode [31] [32]. This fibrotic capsule electrically insulates the electrode from nearby neurons, increasing impedance and degrading signal quality [33] [34]. The chronic inflammatory response can persist for the duration of the implant, continually compromising performance [32].

FAQ 2: Our soft electrode prototypes are difficult to implant without buckling. How can this be overcome? Buckling is a common issue due to the low flexural rigidity of soft materials. Successful strategies involve the use of temporary, biodegradable stiffeners. A widely cited method uses silk fibroin, a nature-derived material, as a supportive shuttle [31]. The electrode is spin-coated with a layer of silk fibroin, which provides the necessary rigidity for insertion into neural tissue. Upon contact with physiological fluids, the silk layer dissolves, leaving the soft, flexible electrode in place, perfectly conforming to the target tissue [31].

FAQ 3: We've applied a bioactive coating, but it seems to degrade or delaminate too quickly in vivo. What are we doing wrong? Coating stability is a significant hurdle. Physically adsorbed coatings (e.g., laminin, collagen) can rapidly desorb or degrade enzymatically, diminishing their intended bioactivity [32]. To improve longevity, shift your strategy to covalent immobilization. For example, the anti-inflammatory drug dexamethasone can be covalently bound to a polyimide electrode surface, ensuring slow, local release over at least two months [35]. Similarly, the neuronal adhesion molecule L1 has been covalently immobilized on silicon, leading to improved recording yield over 16 weeks [32].

FAQ 4: Our conductive polymer coating (PEDOT:PSS) is showing signs of electrochemical instability during chronic stimulation. How can we improve its resilience? Pure conductive polymer coatings can suffer from mechanical fatigue and delamination under prolonged electrical cycling. A proven solution is to use composite materials. Doping PEDOT with negatively charged carbon nanotubes creates a nanofibrous, interpenetrating network that enhances both mechanical robustness and electrical performance [32]. This composite structure promotes cellular process ingrowth, which can further stabilize the interface and has been shown to provide stable recording and higher stimulation efficiency over 12 weeks in vivo [32].

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies for the Field

Protocol: Covalent Immobilization of Dexamethasone on Polyimide

This protocol is based on a recent study that demonstrated reduced immune response and improved chronic stability [35].

- Objective: To create a neural implant with a slow-release anti-inflammatory drug coating.

- Materials:

- Polyimide-based neural electrodes

- Dexamethasone

- Appropriate crosslinking agents (e.g., EDC/NHS chemistry)

- Solvents (DMF, Ethanol)

- Standard cell culture materials for biocompatibility testing (e.g., immune cell lines)

- Methodology:

- Surface Activation: Clean and activate the polyimide surface using an oxygen plasma treatment to generate reactive functional groups (e.g., carboxyl groups).

- Chemical Coupling: Incubate the activated polyimide with dexamethasone in the presence of a crosslinking agent. The study used a specific chemical strategy to enable covalent binding, ensuring the drug is not merely adsorbed [35].

- Washing and Sterilization: Thoroughly rinse the coated devices in sterile solvent to remove any unbound drug molecules. Sterilize using ethylene oxide or low-temperature plasma.

- In Vitro Validation:

- Release Kinetics: Soak the coated implant in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 37°C and use high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to quantify drug release over time. The cited method demonstrated release for a critical period of at least two months [35].

- Biocompatibility: Culture immune cells (e.g., macrophages) on the coated surface and assay for inflammatory markers (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β) to confirm reduced activation.

- In Vivo Application: Implant the functionalized device in the target neural tissue (e.g., peripheral nerve). After 4-6 weeks, perform histological analysis to quantify the density of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-positive astrocytes and IBA1-positive microglia around the implant site, comparing against uncoated controls [35].

Protocol: Characterizing the Foreign Body Response to Soft Implants

This guideline provides a framework for comprehensively evaluating new bio-inspired neural interfaces [36].

- Objective: To systematically assess the biocompatibility and functional integration of a soft neural electrode.

- Materials:

- Soft electrode (e.g., made from PDMS, SU-8, or conductive hydrogel)

- Electrochemical impedance spectrometer

- Histology reagents (fixatives, antibodies for neurons, astrocytes, microglia)

- Confocal microscope

- Methodology:

- Pre-implantation Characterization:

- Mechanical Testing: Measure the elastic modulus of your device material using a tensile tester or atomic force microscopy (AFM). Compare this to the modulus of neural tissue (~1-30 kPa) [27].

- Electrochemical Analysis: Perform cyclic voltammetry and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) in PBS to establish baseline charge storage capacity and impedance [36].

- In Vivo Implantation: Surgically implant the device into the target neural region of an animal model (e.g., rat cortex). Ensure all procedures are approved by the relevant Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

- Chronic Functional Monitoring:

- Signal Quality: Regularly record neural signals (local field potentials and/or single-unit activity) over the implantation period (e.g., 4-16 weeks). Track the number of recordable units and signal amplitude [33].

- Impedance Tracking: Periodically measure the electrode-tissue impedance at 1 kHz. A steady increase often correlates with fibrotic encapsulation [36].

- Endpoint Histological Analysis:

- Tissue Fixation and Sectioning: Perfuse the animal and extract the brain/nerve containing the implant. Section the tissue for immunohistochemistry.

- Immunostaining and Quantification: Stain tissue sections for:

- Neurons (NeuN): To quantify neuronal survival and density near the interface.

- Astrocytes (GFAP): To visualize and quantify astrocytic scarring.

- Microglia/Macrophages (IBA1): To assess the neuroinflammatory response.

- Use image analysis software to count cells and measure the thickness of the glial scar surrounding the implant track [31] [34].

- Pre-implantation Characterization:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Anti-Fibrosis Neural Interfaces

| Item Name | Function/Benefit | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Soft Substrates (PDMS, Polyimide) [27] | Provides flexible, tissue-matching mechanical base for electrodes (Elastic modulus ~kPa-MPa). Reduces mechanical mismatch and micromotion damage. | PDMS is gas-permeable and optically clear; Polyimide is a robust, microfabrication-friendly insulator. |

| Conductive Polymers (PEDOT:PSS) [27] [32] | Coating or stand-alone electrode material. Lowers impedance, increases charge injection capacity. Intrinsically softer than metals. | Can be doped with biologics (e.g., drugs) or mixed with nanotubes for enhanced stability [32]. |

| Dexamethasone [35] | Potent anti-inflammatory drug. Local release suppresses the foreign body response and subsequent fibrosis. | Covalent binding to the implant surface enables slow release over months, critical for long-term efficacy [35]. |

| Nature-Derived Materials (Hyaluronic Acid, Laminin, Silk Fibroin) [31] [32] | Bioactive coatings or structural elements. Mimic the extracellular matrix, providing familiar cues to neural cells and reducing inflammation. | Silk fibroin is excellent as a biodegradable stiffener. Hyaluronic acid has inherent anti-inflammatory properties [31]. |

| Zwitterionic Polymers (PSBMA) [32] | "Anti-fouling" surface coating. Creates a hydration layer that resists non-specific protein adsorption, the first step in the FBR. | Must be covalently grafted for stability. Can be further functionalized with bioactive molecules for multifunctionality [32]. |

Visualizing Core Concepts: Pathways and Workflows

Foreign Body Response Cascade

This diagram outlines the key cellular events following neural electrode implantation that lead to fibrosis and device failure.

Bio-integrative Coating Strategy Workflow

This flowchart illustrates the decision-making process for selecting and applying a bio-integrative coating to a neural device.

Understanding the Foreign Body Response (FBR) Against Neural Implants

The foreign body response is an immune-mediated reaction that leads to the rejection of implanted devices through a cascade of inflammatory events and wound-healing processes, resulting in fibrosis. This fibrotic capsule can disrupt biosensing functions, cut off nourishment for cell-based implants, and ultimately lead to device failure, presenting a fundamental challenge for chronic neural interfaces [37].

The following table summarizes the key cellular players and their roles in the FBR cascade:

Table 1: Key Cellular Events in the Foreign Body Response to Neural Implants

| Time Phase | Key Cells Involved | Primary Functions & Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Early (Hours-Days) | Neutrophils | First responders; secrete proteolytic enzymes and reactive oxygen species that can damage implants [37]. |

| Acute (Days) | Monocytes/Macrophages | Differentiate from infiltrating monocytes; secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-8, MCP-1) and attempt to phagocytose the implant [37]. |

| Chronic (Days-Weeks) | Foreign Body Giant Cells (FBGCs) | Formed by macrophage fusion; presence indicates a persistent inflammatory state [37]. |

| Late (Weeks+) | Fibroblasts/Myofibroblasts | Produce collagen and extracellular matrix (ECM), leading to the formation of a dense, fibrotic capsule that isolates the implant [37]. |

The diagram below illustrates the key signaling pathways and cellular interactions in the FBR.

Experimental Protocols for Developing Drug-Eluting Coatings

Covalent Binding of Dexamethasone to Polyimide

This protocol details a method for creating a neural implant coating that provides sustained local release of an anti-inflammatory drug [38].

Key Reagents:

- Polyimide substrate (e.g., BPDA-PDA)

- Dexamethasone (DEX)

- Chemical agents for surface activation (e.g., linkers for covalent binding)

Methodology:

- Surface Activation: Chemically modify the surface of the polyimide electrode to create reactive groups for drug binding.

- Covalent Conjugation: Covalently bind DEX molecules to the activated surface using a specific chemical strategy. This step is crucial for achieving sustained release, as it prevents the rapid "burst release" of the drug.

- Characterization: Verify successful binding and quantify the drug loading on the surface using techniques like X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) or Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy.

- Release Kinetics: Perform in vitro elution studies by incubating the coated substrate in a buffer (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline) at 37°C. Sample the buffer at regular intervals over several weeks and use High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) to measure the concentration of released DEX, confirming a release duration of at least 9 weeks [38].

Protein Nanofilm-Based Drug Delivery System

This protocol describes a versatile method for coating implants with a drug-loaded protein nanofilm, which is also applicable to neural interfaces [39].

Key Reagents:

- Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA)

- Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP)

- Sodium Alginate (SA)

- Anti-fibrotic drug (e.g., Rapamycin)

Methodology:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a phase transition solution by premixing BSA and SA in an aqueous solution.

- Reduction and Aggregation: Add TCEP (pH 4.5) to the BSA/SA mixture. TCEP reduces the intramolecular disulfide bonds in BSA, triggering its unfolding and aggregation into β-sheet-stacking nanoparticles.

- Coating Formation: Immerse the implant (e.g., a catheter or electrode shank) in the phase transition solution. The protein nanoparticles self-assemble at the solid-liquid interface, forming a nanofilm on the implant surface.

- Drug Loading: The anti-fibrotic drug can be incorporated into the nanofilm during the assembly process. The intrinsic nanochannels (approximately 2.16 nm) within the film provide a pathway for controlled drug diffusion [39].

- Film Characterization: Control the nanofilm thickness (10–200 nm) by adjusting BSA concentration, SA ratio, and incubation time. Confirm the structural change of BSA from α-helix to β-sheet using Circular Dichroism (CD) and FTIR.

In Vivo Evaluation of Coating Efficacy

A standardized protocol for assessing the performance of coated neural implants in animal models is critical.

Animal Model: Rats or rabbits are commonly used. For peripheral nerve implants, the sciatic nerve is a frequent target [38].

Surgical Implantation:

- Anesthetize the animal and perform an aseptic surgical procedure to expose the target nerve or brain region.

- Implant the coated device alongside appropriate controls (e.g., uncoated device, polymer-only coated device).