Strategies for Minimizing Foreign Body Response in Bioelectronics: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of innovative strategies to mitigate the foreign body response (FBR) against implantable bioelectronic devices.

Strategies for Minimizing Foreign Body Response in Bioelectronics: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of innovative strategies to mitigate the foreign body response (FBR) against implantable bioelectronic devices. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational knowledge of FBR immunology with cutting-edge methodological advances in biomaterial science, troubleshooting for device optimization, and comparative validation of emerging technologies. The content explores how recent breakthroughs in immunomodulatory materials, surface engineering, and device design are overcoming the critical challenge of FBR, thereby enhancing the longevity and performance of next-generation bioelectronics for therapeutic and diagnostic applications.

Understanding the Foreign Body Response: The Immune Battle Against Implanted Bioelectronics

FAQs: Understanding the Foreign Body Response

What is the Foreign Body Response (FBR) and why is it a critical problem for implantable bioelectronics?

The Foreign Body Response is an immune-mediated reaction to implanted materials, culminating in the formation of a dense, collagenous fibrotic capsule that isolates the device [1] [2]. For bioelectronics, this is a fundamental challenge because the fibrotic capsule can impair device function by disrupting the critical interface with the target tissue [3] [4]. This can lead to signal degradation in recording electrodes, increased impedance for stimulating electrodes, and ultimately, device failure [5] [6]. It is estimated that FBR contributes to the failure of approximately 30% of breast implants and about 10% of all other implantable medical devices, presenting a significant hurdle for long-term therapies [3] [7].

What are the key cellular stages of the FBR cascade?

The FBR is a sequential process that can be broken down into several key stages [1] [8]:

- Protein Adsorption: Within seconds of implantation, blood plasma proteins (e.g., albumin, fibrinogen, fibronectin) non-specifically adsorb to the implant surface, forming a provisional matrix [3] [4].

- Acute Inflammation: Neutrophils are the first responders (within hours to 2 days), attempting to clear the foreign material [1] [2]. They are quickly followed by monocytes that differentiate into pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages [1] [3].

- Chronic Inflammation and FBGC Formation: Unable to phagocytose large implants, macrophages undergo "frustrated phagocytosis" and fuse to form multinucleated Foreign Body Giant Cells (FBGCs), a hallmark of chronic FBR [1] [3].

- Fibrotic Encapsulation: Activated macrophages and other immune cells release factors like TGF-β, which drive fibroblast recruitment, their differentiation into collagen-secreting myofibroblasts, and the eventual formation of an avascular, dense fibrous capsule [1] [8].

Which signaling pathways are most critical for driving fibroblast-to-myofibroblast differentiation, and can they be targeted?

The differentiation of fibroblasts into matrix-depositing myofibroblasts is a pivotal event in fibrosis, primarily driven by the TGF-β (Transforming Growth Factor-Beta) signaling pathway [1] [8]. TGF-β activates both Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways (including Rho/ROCK) to promote the expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and collagen synthesis [8]. The IL-17 signaling pathway has also been implicated in promoting fibrosis, with senescent cells potentially exacerbating this effect [8]. These pathways are prime targets for therapeutic intervention, with research exploring drugs like tranilast (an anti-fibrotic) and ROCK inhibitors to disrupt this critical step [8].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Hurdles in FBR Research

Problem: High Variability in Capsule Thickness Measurements in Animal Models

Inconsistent capsule thickness data can stem from uncontrolled variables related to the implant or the host [7].

- Solution:

- Standardize Implant Properties: Ensure consistency in implant size, shape, surface topography, and, critically, mechanical stiffness (modulus) across experimental groups, as all of these parameters are known to influence the degree of FBR [3] [7].

- Control for Biological Variability: Implant multiple test materials within the same animal in a controlled configuration to minimize inter-animal variability, as demonstrated in studies with mice [7].

- Follow Systematic Histology: Use standardized protocols for tissue harvesting, sectioning orientation, and staining (e.g., Masson's Trichrome for collagen, H&E for general structure). Measure capsule thickness at multiple, predefined locations around the implant circumference.

Problem: Rapid Biofouling on Sensor Surfaces Impairs Function

Non-specific protein adsorption is the initiating event of FBR and can immediately foul biosensor surfaces [2].

- Solution:

- Implement Anti-Fouling Coatings: Utilize surface modifications with hydrophilic or zwitterionic polymers (e.g., poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) pHEMA, methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine (MPC)-based polymers) that create a hydration layer to resist protein adsorption [3] [8].

- Optimize Surface Topography: Introduce micro- or nano-scale surface textures. For example, porous pHEMA scaffolds with 34 μm porosity have been shown to elicit a less dense capsule and increased vascularization compared to non-porous or differently porous versions [3].

- Consider Novel Material Platforms: Investigate the use of intrinsically anti-fouling bulk materials, such as the EVADE (easy-to-synthesize vinyl-based anti-FBR dense elastomers) platform, which has demonstrated negligible fibrotic encapsulation for up to one year in rodent models [7].

Problem: Inconsistent Macrophage Polarization in In Vitro Models

It is challenging to replicate the dynamic switch from pro-inflammatory (M1) to pro-healing/pro-fibrotic (M2) macrophage phenotypes in cell culture [1].

- Solution:

- Use Defined Polarizing Cytokines: Prime primary macrophages or cell lines with specific cytokine cocktails (e.g., IFN-γ + LPS for M1; IL-4 + IL-13 for M2) before exposing them to your material [1].

- Monitor Polarization Status: Use a combination of surface marker analysis (e.g., flow cytometry for CCR7, CD206) and cytokine secretion profiling (e.g., ELISA for TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, TGF-β) to confirm and track polarization states [1] [7].

- Co-culture with Fibroblasts: Establish a more complex in vitro model by co-culturing macrophages with fibroblasts in the presence of the biomaterial to better mimic the cellular crosstalk that occurs in vivo [1].

Quantitative Data: FBR Timelines and Device Impact

Table 1: Key Cell Types and Their Roles in the FBR Cascade

| Cell Type | Time of Appearance | Primary Role in FBR | Key Secretions/Markers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophils | Hours to 2 days [2] [4] | First responders; release proteolytic enzymes and ROS; attempt to phagocytose debris [1] [2] | ROS, MMPs, Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) [2] |

| Macrophages (M1) | Days 2-3, peaking in acute phase [1] [4] | Pro-inflammatory; attempt phagocytosis; secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines [1] [3] | TNF-α, IL-6, CCR7 [1] [7] |

| Foreign Body Giant Cells (FBGCs) | Multiple days, chronic phase [1] [2] | Result from macrophage fusion; persistent "frustrated phagocytosis" [1] [3] | ROS, enzymes for degradation [1] [2] |

| Macrophages (M2) | Later in chronic phase, as inflammation resolves [1] [3] | Anti-inflammatory; promote tissue remodeling and fibrosis [1] [3] | TGF-β, IL-10, PDGF [1] [3] |

| Fibroblasts / Myofibroblasts | From ~day 7, numbers peak around day 28 [2] [8] | Deposit collagen and ECM; contract the capsule [1] [8] | Collagen I/III, α-SMA (myofibroblast marker) [3] [8] |

Table 2: Impact of FBR on Specific Medical Devices

| Device Category | Common FBR-Related Issues | Consequences | Reported Failure/Complication Rates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Implants | Capsular contracture, granuloma formation, pain [1] [3] | Implant hardening, distortion, pain, need for revision surgery [1] [8] | 8-30% of patients experience capsular contracture; up to 54% recurrence after reoperation [1] [3] |

| Neural Interfaces | Fibrotic encapsulation of electrodes, inflammation [3] [5] | Increased electrode impedance, signal attenuation or loss, stimulation failure [5] [6] | A primary cause of chronic recording instability and failure of microelectrode arrays [5] [6] |

| Continuous Subcutaneous Infusion Catheters | Fibrosis around catheter tip [7] | Blocked fluid flow, impaired drug absorption (e.g., insulin), necessitates frequent replacement [7] | Commercial catheters often require replacement every 2-3 days due to FBR [7] |

| Cell Encapsulation Devices | Fibrotic overgrowth of the device [3] | Isolation of encapsulated cells, hypoxia, nutrient deprivation, therapeutic failure [3] | A major barrier to long-term efficacy of encapsulated cell therapies [3] |

Experimental Protocols for Key FBR Assays

Protocol: Subcutaneous Implantation and Capsule Histomorphometry in Rodents

This is a standard in vivo model for evaluating the fibrotic response to biomaterials [7].

- Material Preparation: Sterilize test materials (e.g., polymer discs, 0.5-1.0 cm diameter). Critical: Control for material stiffness, size, and surface topography to isolate the variable of interest [7].

- Surgical Implantation: Anesthetize the animal (e.g., C57BL/6 mouse) and make a dorsal midline incision. Create subcutaneous pockets by blunt dissection on both flanks. Insert one material per pocket. Close the incision with sutures or wound clips [7].

- Explanation and Tissue Harvest: Euthanize the animal at the predetermined endpoint (e.g., 2 weeks for acute inflammation, 4 weeks or longer for fibrosis). Carefully excise the implant with the surrounding tissue envelope intact.

- Histological Processing: Fix the explant in 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrate, and embed in paraffin. Section the tissue into 5-10 μm thick slices and mount on slides.

- Staining and Analysis:

- H&E Staining: For general tissue structure and cellularity.

- Masson's Trichrome Staining: To specifically visualize collagen (stains blue) and the fibrous capsule.

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC): For specific cell types (e.g., F4/80 for macrophages, α-SMA for myofibroblasts) or proteins (e.g., S100A8/A9) [7].

- Capsule Thickness Measurement: Using stained sections, take multiple (e.g., 10-20) perpendicular measurements of the capsule thickness around the entire implant under a microscope. Calculate the average and standard deviation [7].

Protocol: Profiling Macrophage Polarization In Vitro

This protocol helps characterize the immune response to a material by assessing macrophage phenotype.

- Cell Culture: Use a primary macrophage cell line (e.g., bone marrow-derived macrophages from mice) or an immortalized line (e.g., RAW 264.7).

- Polarization and Seeding:

- Differentiate monocytes into M0 macrophages using M-CSF.

- Pre-polarize macrophages by treating with LPS + IFN-γ (for M1) or IL-4 + IL-13 (for M2) for 24 hours.

- Seed the polarized macrophages onto the material surfaces or tissue culture plastic controls.

- Analysis (24-48 hours post-seeding):

- Gene Expression: Perform qRT-PCR to analyze expression of M1 markers (e.g., iNOS, TNF-α, IL-6) and M2 markers (e.g., Arg1, CD206, TGF-β).

- Protein Secretion: Collect cell culture supernatant and analyze cytokine levels using ELISA kits for M1 (TNF-α, IL-6) and M2 (TGF-β, IL-10) associated cytokines [7].

- Surface Markers: Detach cells and analyze surface markers characteristic of M1 (e.g., CCR7) and M2 (e.g., CD206) phenotypes via flow cytometry [1].

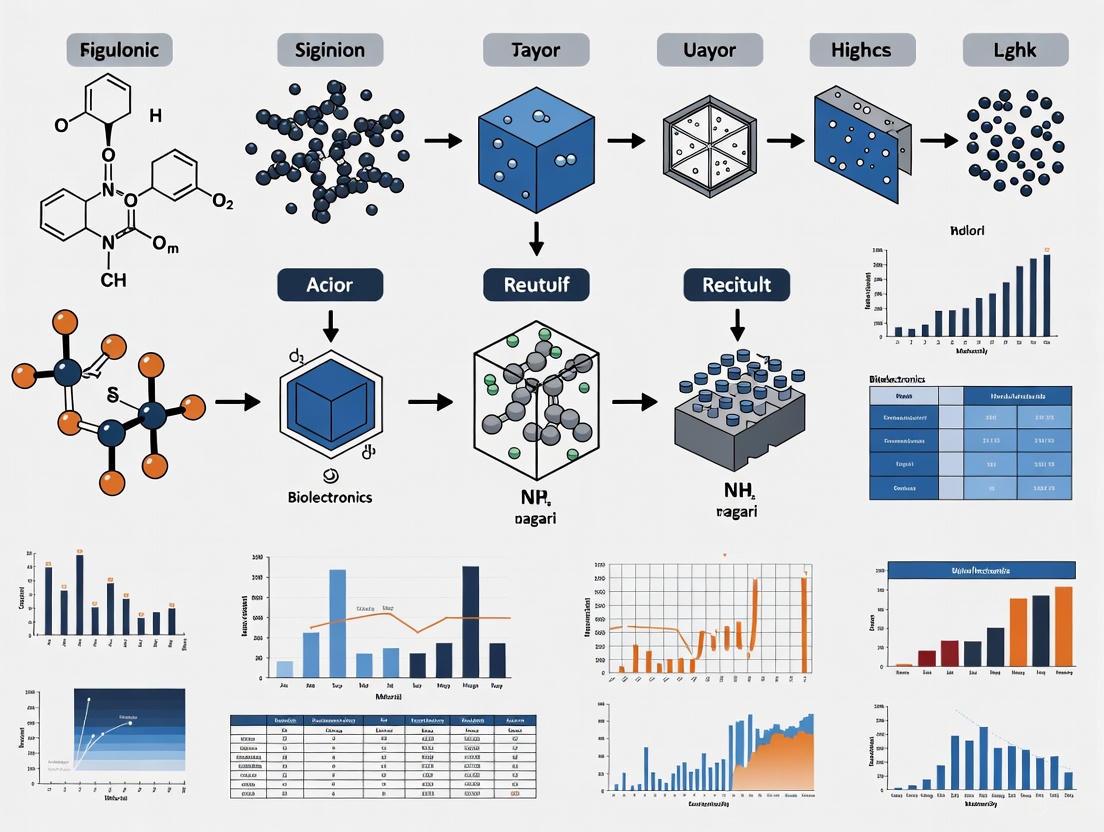

Visualization of the FBR Cascade and Key Pathways

Key Fibrogenic Signaling Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents for FBR and Fibrosis Research

| Reagent / Material | Function/Application | Example Use in FBR Context |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Cytokines (TGF-β, IL-4, IL-13) | Directly polarize macrophages or stimulate fibroblast differentiation in vitro [1] [8]. | Used in cell culture to model the pro-fibrotic microenvironment and study myofibroblast differentiation [1]. |

| α-SMA (Alpha-Smooth Muscle Actin) Antibody | A standard marker for identifying activated myofibroblasts via immunohistochemistry or flow cytometry [3] [8]. | Critical for quantifying the number of pro-fibrotic cells in the tissue capsule surrounding an explanted device [3]. |

| Masson's Trichrome Stain | Histological stain that differentially colors collagen fibers blue, muscle fibers red, and nuclei dark brown/purple [7]. | The primary method for visualizing and quantifying the extent and density of the collagenous fibrotic capsule in tissue sections [7]. |

| EVADE Elastomers | A novel platform of immunocompatible elastomers that intrinsically resist FBR [7]. | Used as a positive control material or a next-generation substrate for devices to achieve long-term, minimal-fibrosis implantation [7]. |

| Clodronate Liposomes | A tool for in vivo depletion of macrophages [2]. | Used to experimentally confirm the central role of macrophages in FBR; macrophage depletion prevents fibrotic capsule formation [2]. |

| S100A8/A9 Inhibitors / Knockout Models | Target specific alarmin proteins implicated in the pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic cascade [7]. | Used to investigate the role of S100A8/A9 in FBR and as a potential therapeutic strategy to attenuate fibrosis [7]. |

The foreign body response (FBR) is an inevitable biological reaction to any implanted biomaterial or medical device. For bioelectronics researchers, understanding this process is critical to improving the long-term functionality and stability of implants. The FBR is a coordinated sequence of events involving the immune system and connective tissues, ultimately leading to the encapsulation of the device in a collagenous, scar-like capsule. This fibrotic tissue can isolate the implant from its target tissue, leading to device failure—a significant obstacle for neural interfaces, biosensors, and other implantable bioelectronics. The core cellular players driving this response are macrophages, foreign body giant cells (FBGCs), and fibroblasts. This guide provides troubleshooting advice and foundational knowledge to help researchers identify and mitigate the FBR in their experimental models.

FAQ: Understanding the Key Cellular Players

What are the main phases of the FBR?

The FBR progresses through well-defined, overlapping phases [9] [10]:

- Protein Adsorption: Within seconds of implantation, blood-derived proteins (e.g., albumin, fibrinogen) non-specifically adsorb to the biomaterial surface, forming a provisional matrix [10].

- Acute Inflammation: Neutrophils are the first responders, infiltrating the site within minutes to hours. They secrete factors that recruit monocytes [10].

- Chronic Inflammation: Monocytes arrive and differentiate into macrophages, which populate the implant interface. These cells attempt to phagocytose the material [10].

- FBGC Formation and Fibrosis: If phagocytosis fails (due to the implant's size), macrophages fuse into multinucleated Foreign Body Giant Cells (FBGCs). This phase is accompanied by the recruitment and activation of fibroblasts, which deposit collagen and other extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, leading to the formation of a fibrous capsule [11] [9] [10].

What roles do macrophages and FBGCs play in device failure?

Macrophages are the primary coordinators of the FBR. They are highly plastic cells that can adopt different functional phenotypes, often broadly categorized as pro-inflammatory (M1) or pro-healing/anti-inflammatory (M2) [11] [9].

- M1 Macrophages: Driven by signals like LPS or IFN-γ, they secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) [9]. They dominate the early, inflammatory phase and can directly damage device materials through enzymatic degradation and oxidative stress [10].

- M2 Macrophages: Induced by cytokines like IL-4 and IL-13, they secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10) and factors like TGF-β that promote tissue repair and fibroblast activation [11] [9]. A transition to an M2-dominated environment is associated with the fibrotic phase.

Foreign Body Giant Cells (FBGCs) form when macrophages fuse in an attempt to engulf large foreign materials, a process termed "frustrated phagocytosis" [12]. FBGCs persist at the material-tissue interface and secrete large amounts of degradative enzymes and ROS, leading to significant biomaterial deterioration [10] [12]. They also contribute to a pro-fibrotic microenvironment, stimulating fibroblasts and promoting excessive ECM deposition [12].

How do fibroblasts contribute to device failure?

Fibroblasts are recruited to the implant site by signals from macrophages and platelets [11] [9]. Their primary role in FBR is the production and remodeling of the ECM. Upon activation by factors like TGF-β, they differentiate into myofibroblasts, which express α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and possess high contractile activity [9]. The excessive deposition and contraction of dense, cross-linked collagen by myofibroblasts leads to the formation of a fibrotic capsule. This capsule can:

- Isolate the device from its target tissue (e.g., neurons), severely impairing the function of recording or stimulating electrodes [10] [5].

- Contract over time, mechanically stressing both the implant and the surrounding host tissue, potentially leading to device displacement or damage [9].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Problem 1: Excessive Fibrous Encapsulation

Observed Issue: A thick, dense collagenous capsule forms around the implant, leading to functional isolation.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Tips | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Prolonged M2 macrophage activity & FBGC persistence | Immunostaining for M2 markers (e.g., CD206, Arg1) and FBGCs (multinucleated cells) at the interface. | Modulate macrophage polarization using biomaterial properties (e.g., topography, stiffness) [11]. Consider local delivery of CSF1R inhibitors to disrupt FBGC formation [11] [9]. |

| Sustained TGF-β signaling | Measure TGF-β levels in peri-implant tissue via ELISA. Stain for α-SMA+ myofibroblasts. | Use biomaterials that absorb or sequester TGF-β. Explore small molecule inhibitors of TGF-β signaling pathways. |

| Excessive stiffness mismatch | Characterize the Young's modulus of your material versus the target tissue (e.g., brain ~1 kPa) [13]. | Use softer, more compliant materials like specific polymers (e.g., Polyimide, PDMS) or hydrogels to minimize mechanical activation of fibroblasts [9] [13]. |

Problem 2: Chronic Inflammation and Material Degradation

Observed Issue: Inflammation fails to resolve, and the implant material shows signs of surface degradation, cracking, or leaching.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Tips | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| "Frustrated phagocytosis" and persistent M1 activation | Immunostaining for M1 markers (e.g., iNOS), and detecting ROS/LOS production. SEM imaging of material surface. | Design smoother surface topographies or materials that evade protein fouling. Incorporate anti-inflammatory agents (e.g., IL-10) into the material coating [11]. |

| Material toxicity or inappropriate surface chemistry | In vitro cytotoxicity assays (e.g., PC-12 neural cells, NRK-49F fibroblasts) [13]. | Select biocompatible polymers with a proven track record (e.g., Polyimide, Polylactide) and avoid cytotoxic materials like some PEGDA formulations [13]. Functionalize surfaces with immunomodulatory groups [14]. |

Problem 3: Inconsistent FBR in Animal Models

Observed Issue: High variability in the severity of the FBR between subjects in a study.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Tips | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Surgical technique and tissue trauma | Standardize and document surgical procedures meticulously. Monitor for excessive bleeding or infection. | Train all surgeons to a high level of proficiency. Use consistent implantation protocols and tools. |

| Uncontrolled host factors | Use genetically similar animal cohorts. Monitor for pre-existing conditions. | Utilize inbred rodent strains to minimize genetic variability. Ensure animals are of similar age and health status. |

| Material property variability | Characterize material surface properties (roughness, chemistry) between batches. | Implement strict quality control (QC) checks for all fabricated devices and materials. |

Experimental Protocols for Studying FBR

In Vitro Model for Macrophage Fusion and FBGC Formation

This protocol allows for the quantitative study of factors driving macrophage fusion, a key event in the FBR [12].

- Primary Cell Isolation: Isolate CD14+ monocytes from human peripheral blood using density gradient centrifugation and magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS).

- Macrophage Differentiation: Culture monocytes in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 25-100 ng/mL recombinant human M-CSF for 72 hours to differentiate them into macrophages.

- Fusogenic Stimulation: Replace the medium with fresh medium containing M-CSF and a fusogenic cytokine stimulus, typically IL-4 (10 ng/mL) and/or IL-13 (10 ng/mL).

- Culture and Analysis:

- Culture cells on a permissive substrate (e.g., Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) films) for up to 28 days, replacing the media every 3-4 days.

- To quantify fusion, fix cells at desired time points and stain with May-Grünwald/Giemsa.

- Image and count nuclei. A Fusion Index can be calculated as: (Number of nuclei within multinucleated cells / Total number of nuclei counted) × 100 [12].

- FBGCs are typically defined as cells containing ≥4 nuclei.

In Vitro Coculture Model for Macrophage-Fibroblast Interactions

This model investigates the paracrine signaling between macrophages and fibroblasts [12].

- Cell Culture:

- Differentiate macrophages from monocytes as described above.

- Culture fibroblasts (e.g., NRK-49F line [13]) in standard DMEM medium.

- Setup:

- Direct Contact: Seed macrophages and fibroblasts together on the material of interest.

- Indirect Contact: Use transwell systems, where one cell type is cultured on a permeable insert and the other in the well below, allowing exchange of soluble factors but preventing physical contact.

- Analysis:

- Collect conditioned media and analyze secreted cytokines (e.g., TGF-β, PDGF, IL-10) using ELISA [12].

- Assess fibroblast activation by immunostaining for markers like α-SMA or by measuring collagen production (e.g., Sirius Red staining).

Key Signaling Pathways and Cellular Crosstalk

The progression of the FBR is governed by complex crosstalk between macrophages and fibroblasts. The diagram below illustrates the core signaling axes and cellular transitions.

Cellular and Molecular Drivers of the Foreign Body Response

A critical mechanical interaction was discovered in fibrillar collagen matrices, where contracting fibroblasts generate long-range deformation fields [15]. Macrophages can sense these mechanical cues from several hundred micrometers away and actively migrate towards the source via α2β1 integrin and stretch-activated channels, independent of chemotaxis [15]. This represents a powerful mechanical crosstalk mechanism that recruits macrophages to sites of active remodeling.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

The table below lists essential reagents and materials used in FBR research, based on the protocols and studies cited.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Human M-CSF | Differentiates isolated human monocytes into macrophages in vitro. | Used at 25-100 ng/mL to generate macrophages for fusion assays [12]. |

| Recombinant Human IL-4 / IL-13 | Key cytokines that drive macrophage polarization to an M2 phenotype and promote fusion into FBGCs. | Used at 10 ng/mL each to stimulate FBGC formation on PET films [12]. |

| Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) | A permissive substrate used in in vitro models to study macrophage adhesion and fusion. | Sterilized PET films (0.1 mm thick) used as a standard surface for FBGC formation studies [12]. |

| TAK-242 (CLI-095) | A potent inhibitor of TLR4 signaling. Used to investigate the role of innate immune activation in macrophage fusion. | Added at 1 µg/mL to cultures to inhibit TLR4 and assess its impact on large FBGC formation [12]. |

| Anti-α-SMA Antibody | Marker for identifying activated myofibroblasts in tissue sections or cell cultures via immunostaining. | Used to quantify the extent of fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition (FMT) in fibrotic tissue [9]. |

| Polyimide (PI) | A polymer with high biocompatibility for neural interfaces, causing minimal FBR. | Identified in a screen of 10 polymers as showing the highest compatibility with neural and fibroblast cells [13]. |

| PEGDA | A hydrogel material that can elicit a strong FBR, useful as a positive control for fibrosis studies. | Showed cytotoxic effects, low cell adhesion, and strong FBR with fibrosis in comparative studies [13]. |

| CSF1R Inhibitor | Pharmacological agent that blocks the colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor, crucial for macrophage survival and FBGC formation. | In vivo inhibition resulted in reduced fibrous encapsulation and FBGC formation [11] [9]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the foreign body response (FBR) and why is it a critical issue for bioelectronic implants? The foreign body response (FBR) is a complex, innate immune reaction triggered by the implantation of a medical device. It begins with protein adsorption on the implant surface, followed by a cascade of immune cell recruitment (neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages), chronic inflammation, and the eventual formation of a dense, collagen-rich fibrous capsule that isolates the device [3] [16]. This response is a primary cause of long-term bioelectronic device failure. The fibrous capsule acts as an insulating barrier, severely compromising the device's ability to communicate electrically with the target tissue by increasing impedance at the tissue-device interface [3] [17]. It can also block analyte diffusion for biosensors and impede drug delivery from implantable pumps [3].

Q2: What are the direct functional consequences of the fibrous capsule on my bioelectronic device's performance? The fibrous capsule directly degrades device performance through several mechanisms:

- Increased Interface Impedance: The avascular, collagen-dense capsule electrically insulates the electrode, drastically increasing impedance and weakening signal transmission for both recording and stimulation [3] [17].

- Signal Degradation: For recording electrodes, this results in a decreased signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), making neural signals weaker and harder to resolve. For stimulating devices, more power is required to achieve the same therapeutic effect, which can drain batteries faster and cause tissue damage [6].

- Device Isolation: The capsule can physically displace the device from its intended target, further reducing signal fidelity and stimulation efficiency [3].

Q3: Beyond fibrosis, what other aspects of FBR should I be monitoring in my experiments? While collagen deposition is a key endpoint, a comprehensive assessment should include:

- Immune Cell Infiltration: Monitor the presence and polarization of macrophages. A persistent population of pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages (expressing markers like CCR7) is a driver of chronic inflammation and fibrosis, whereas a transition to anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages is associated with resolution [7] [3] [18].

- Inflammatory Cytokines: Analyze the expression of pro-inflammatory biomarkers such as S100A8/A9, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β in the peri-implant tissue. Their upregulation indicates an active and damaging inflammatory phase of the FBR [7] [18].

- Myofibroblast Activation: The differentiation of fibroblasts into α-Smooth Muscle Actin (α-SMA) positive myofibroblasts is a critical step in the formation of a contractile fibrous capsule, which can mechanically distort both the tissue and the implant [3] [18].

Q4: Are certain implant materials more likely to trigger a severe FBR? Yes, the material's chemical and physical properties fundamentally dictate the severity of the FBR. Historically used rigid materials like metals and silicon (with a Young's modulus in the GPa range) have a significant mechanical mismatch with soft tissues (kPa range), promoting inflammation and fibrosis [6]. Among polymers, materials like PEGDA have been shown to elicit strong FBR, while others like polyimide (PI), polylactide (PLA), and polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) show better, though not perfect, compatibility [13]. Emerging research focuses on intrinsically immunocompatible materials, such as certain semiconducting polymers and hydrogels, which are designed to minimize immune activation from the outset [7] [18] [19].

Quantitative Data: Documenting the Impact of FBR

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies, illustrating the measurable impact of FBR and the efficacy of mitigation strategies.

Table 1: Quantitative Consequences of FBR and Efficacy of Mitigation Strategies

| Metric of Interest | Control / Baseline Material | Performance of Advanced Material / Strategy | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fibrous Capsule Thickness | PDMS: 45-135 μm (in mice) | EVADE Elastomer (H90): 10-40 μm (in mice) | [7] |

| Collagen Density | Control Semiconducting Polymer: ~25% | Selenophene-based Polymer with TMO side chain: ~8% (68% decrease) | [18] |

| Macrophage Population | Control Semiconducting Polymer (p(g2T-T)): Baseline | Engineered Polymer (p(g2T-Se)-TMO): ~68% decrease | [18] |

| Myofibroblast Population | Control Semiconducting Polymer (p(g2T-T)): Baseline | Engineered Polymer (p(g2T-Se)-TMO): ~79% decrease | [18] |

| Inflammatory Markers (e.g., CCR-7, TNF-α) | PDMS: Baseline (High) | EVADE Elastomer (H90): ~1/6 to 1/8 fold reduction | [7] |

| Impedance at Interface | Conventional non-adhesive interfaces prone to fibrosis | Adhesive Nonfibrotic Bioelectronics (ANB): Stable, low impedance (~0.76 kΩ at 1 kHz) maintained for 12 weeks | [19] |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing FBR

Protocol 1: In Vivo Histological and Immunohistochemical Analysis of the Tissue-Device Interface

This protocol is fundamental for characterizing the cellular and structural components of the FBR to an implanted bioelectronic device.

- 1. Device Implantation: Implant your bioelectronic device subcutaneously or at the target organ (e.g., brain, peripheral nerve) in an appropriate animal model (e.g., mouse, rat, non-human primate). Ensure a sham or a control material (e.g., PDMS, silicon) is implanted in the same animal for a paired comparison to minimize inter-subject variability [7].

- 2. Explanation and Tissue Harvest: At predetermined endpoints (e.g., 1 week for acute inflammation, 4-12 weeks for chronic fibrosis), euthanize the animal and carefully excise the implant with the surrounding tissue envelope intact [7] [13].

- 3. Tissue Fixation and Sectioning: Fix the tissue-device construct in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 24-48 hours. For stiff implants, careful decalcification may be needed. Embed the tissue in paraffin or optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound and section it into 5-10 μm thick slices using a microtome or cryostat [13].

- 4. Staining and Imaging:

- H&E Staining: Provides a general overview of tissue structure, inflammatory cell infiltration, and the overall capsule architecture [7] [13].

- Masson's Trichrome Staining: Specifically stains collagen fibers blue, allowing for clear visualization and quantification of the fibrous capsule thickness and density [7] [18] [19].

- Immunofluorescence Staining: Use antibodies to label specific cell types and proteins. Key targets include:

- 5. Image Analysis: Use image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ, Fiji) to quantify capsule thickness, collagen density (via blue pixel density in Masson's Trichrome), and fluorescence intensity for cell counts and marker expression [7] [18].

Protocol 2: Molecular Analysis of Inflammatory Biomarkers

This protocol supplements histology by providing quantitative data on gene and protein expression related to the FBR.

- 1. Tissue Sampling: After explant, carefully dissect the tissue immediately adjacent to the implant interface. Snap-freeze the tissue in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C [7] [18].

- 2. RNA Extraction and Quantitative PCR (qPCR): Homogenize the tissue, extract total RNA, and synthesize cDNA. Perform qPCR using primers for fibrosis-related genes (e.g., Collagen type I, Collagen type III) and inflammation-related genes (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β) [18]. Normalize data to housekeeping genes (e.g., Gapdh, Actb).

- 3. Protein Analysis (Antibody Array or ELISA): For a broader profiling of inflammatory mediators, use a proteome profiler antibody array to simultaneously detect the relative levels of multiple cytokines and chemokines (e.g., IFN-γ, GM-CSF, MCP-1, IL-23) in the tissue lysate [7] [18]. Alternatively, use Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays (ELISAs) for quantitative measurement of specific proteins of interest, such as S100A8/A9 [7].

The workflow for these key experimental protocols to assess FBR can be visualized as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for FBR Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application in FBR Research | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| EVADE Elastomers | A class of intrinsically immunocompatible materials used as the bulk substrate for devices to suppress FBR long-term (≥1 year in mice). | Copolymers of HPEMA and ODA (e.g., H90) [7] |

| Engineered Semiconducting Polymers | Conductive polymers with immunomodulatory backbones (e.g., Selenophene) and side chains (e.g., THP, TMO) for bioelectronics with suppressed FBR. | p(g2T-Se)-TMO, p(g2T-Se)-THP [18] [17] |

| Adhesive Hydrogel Interfaces | Bioadhesive layers (e.g., PVA/PAA-based) that create a conformal, nonfibrotic interface on nerves by preventing immune cell infiltration. | Adhesive Nonfibrotic Bioelectronics (ANB) [19] |

| Anti-CD68 Antibody | An antibody for immunofluorescence staining to identify and quantify macrophage populations in the peri-implant tissue. | Used for macrophage detection in vivo [18] |

| Anti-α-SMA Antibody | An antibody for immunofluorescence staining to identify and quantify activated myofibroblasts, the key collagen-producing cells in fibrosis. | Used for myofibroblast detection in vivo [18] |

| Proteome Profiler Antibody Array | A membrane-based array for simultaneously screening the relative levels of multiple inflammation-related cytokines and chemokines from tissue lysates. | Used to profile cytokines like CCR7, IFN-γ, IL-6 [7] [18] |

| S100A8/A9 Inhibitors | Chemical inhibitors or genetic knockout models used to investigate the specific role of these alarmin proteins in driving the fibrotic cascade. | Used in mechanistic studies to confirm S100A8/A9's role in FBR [7] |

Visualizing the FBR Cascade and Its Impact on Device Function

The core mechanism by which FBR initiates and ultimately compromises device function is summarized in the following diagram:

Implantable medical devices and biomaterials inevitably trigger a complex immune-mediated reaction known as the foreign body response (FBR). This process begins immediately upon implantation with protein adsorption and progresses through acute and chronic inflammation, ultimately resulting in fibrotic encapsulation of the device. The dense collagenous capsule that forms can isolate the implant from surrounding tissue, severely compromising the function of bioelectronic devices by impeding signal transduction, increasing interface impedance, and limiting analyte diffusion [18] [3].

For bioelectronic implants, including neural interfaces and biosensors, this fibrotic barrier presents a significant challenge to long-term performance and stability. Research indicates that approximately 90% of failures in common medical devices can be attributed to FBR, with up to 30% of implanted devices failing during their operational lifespan due to immune-mediated reactions [7]. Understanding how specific material properties initiate and modulate this immune cascade is therefore fundamental to designing next-generation bioelectronics with enhanced longevity and functionality.

Fundamental Principles: How Material Properties Guide Immune Activation

The FBR is not a single event but a carefully orchestrated sequence of immune activities. The initial seconds and minutes after implantation are critical, as the material surface immediately interacts with biological components. The following table summarizes the key stages of this process [3]:

Table 1: The Sequential Stages of the Foreign Body Response

| Stage | Time Frame | Key Cellular Events | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Adsorption | Seconds to minutes | Adsorption of blood plasma proteins (albumin, fibrinogen) | Protein layer forms on material surface |

| Acute Inflammation | 1-7 days | Neutrophil infiltration, followed by monocytes | Initial immune recognition and response |

| Chronic Inflammation | Up to 3 weeks | Macrophage activation and polarization | Persistent inflammatory environment |

| Foreign Body Giant Cell Formation | Weeks | Fusion of macrophages into FBGCs | Attempt to phagocytose foreign material |

| Fibrous Encapsulation | Weeks to months | Fibroblast activation, myofibroblast differentiation, collagen deposition | Dense, avascular fibrotic capsule formation |

The properties of an implanted material directly influence the intensity and progression of each stage. Surface characteristics determine the identity and conformation of adsorbed proteins, which in turn influence subsequent immune cell behavior. The physical and chemical properties of the implant can either amplify or dampen the resulting immune response, making material design a powerful tool for modulating FBR [3].

Material Properties That Modulate the Immune Response

Chemical Composition and Molecular Design

The fundamental chemistry of implant materials plays a pivotal role in determining immune compatibility. Recent research has identified several promising molecular strategies:

Selenophene-Based Polymer Backbones: Replacing traditional thiophene units with selenophene in semiconducting polymer backbones has demonstrated significant immunomodulatory potential. This approach can reduce collagen density by approximately 50% compared to conventional materials, likely through suppression of macrophage activation and reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging [18] [20].

Immunomodulatory Side Chains: Functionalization of polymer side chains with specific immunomodulatory groups, such as triazole-tetrahydropyran (THP) and triazole-thiomorpholine 1,1-dioxide (TMO), can further suppress FBR. When combined with selenophene backbone engineering, this strategy has achieved reductions in collagen density of up to 68% in vivo [18].

Tetrahydropyran-Based Elastomers: New elastomer platforms (termed EVADE) incorporating tetrahydropyran ether-derived methacrylate monomers have demonstrated exceptional long-term immune compatibility, showing negligible inflammation and minimal capsule formation in both rodent and non-human primate models for over one year [7].

Physical and Structural Properties

Physical characteristics of implants significantly influence the degree of FBR, often independently of chemical composition:

Table 2: Physical Properties and Their Impact on FBR

| Property | Effects on FBR | Optimal Characteristics for Reduced FBR |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Topography | Determines protein adsorption density, cell adhesion, and macrophage fusion | Micro/nano-scale patterns that discourage focal adhesion formation |

| Stiffness/Mechanical Properties | Mismatch with surrounding tissue causes micromotion and chronic inflammation | Low modulus materials (0.1-0.5 MPa) matching tissue mechanics |

| Size and Shape | Larger implants with sharp edges trigger stronger responses | Smaller, curved geometries that minimize tissue disturbance |

| Surface Roughness | Macroscale roughness promotes fibrosis, nanoscale may reduce it | Controlled nanoscale topography similar to native tissue |

| Porosity | Dense materials prevent vascular integration | 30-160 μm porosity enhances vascularization and reduces capsule density |

The mechanical mismatch between stiff traditional implants and soft biological tissues creates a persistent inflammatory environment. Research shows that softening materials to match the modulus of target tissues (typically in the 0.1-0.5 MPa range for many applications) significantly reduces chronic inflammation and fibrotic encapsulation [7] [21].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing FBR

In Vivo Implantation and Histological Analysis

Objective: To evaluate the extent of foreign body response elicited by implant materials in a subcutaneous model.

Materials Needed:

- Test material samples (sterilized)

- Control materials (e.g., PDMS, medical-grade titanium)

- Animal model (typically C57BL/6 mice or similar)

- Surgical equipment and anesthesia

- Fixatives (4% paraformaldehyde)

- Histological staining reagents (Masson's Trichrome, H&E)

- Immunofluorescence antibodies (CD68 for macrophages, α-SMA for myofibroblasts)

Procedure:

- Fabricate test materials into standardized discs (typically 5-10mm diameter, 0.5-1mm thickness) with controlled surface properties.

- Sterilize materials using appropriate methods (ethanol, UV, or ethylene oxide).

- Anesthetize animals and perform subcutaneous implantation in dorsal regions, with each animal receiving multiple test materials to control for inter-animal variability.

- After predetermined timepoints (typically 1, 4, and 12 weeks), euthanize animals and explant materials with surrounding tissue.

- Fix tissue samples in 4% PFA for 24 hours, process, and embed in paraffin.

- Section tissues (5-7μm thickness) and perform:

- Masson's Trichrome staining to visualize collagen deposition

- H&E staining for general histology

- Immunofluorescence for immune cell markers (CD68, α-SMA)

- Quantify capsule thickness, cellular density, and collagen density using image analysis software.

- Isolate RNA from peri-implant tissue for qPCR analysis of collagen types I and III, and inflammatory markers [18] [7].

Cytokine and Proteomic Profiling

Objective: To characterize the inflammatory microenvironment surrounding implants.

Procedure:

- Implant test materials as described in Section 4.1.

- After 2-4 weeks, harvest tissue immediately adjacent to implants.

- Homogenize tissues in appropriate lysis buffers with protease inhibitors.

- Analyze inflammatory profiles using:

- Proteome profiler antibody arrays for simultaneous detection of multiple cytokines and chemokines

- ELISA for specific cytokines of interest (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10)

- Quantify expression of pro-inflammatory (CCR7, IFN-γ, GM-CSF, MCP-1, IL-23, IL-6, IL-1β) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10, IL-4) biomarkers to determine the balance of immune activation [18] [7].

Functional Assessment in Bioelectronic Devices

Objective: To evaluate the functional impact of FBR on device performance.

Procedure:

- Fabricate OECTs or other bioelectronic devices using test semiconducting polymers.

- Implant devices in relevant anatomical locations (subcutaneous, neural, muscular).

- Monitor electrical performance parameters over time:

- Charge carrier mobility

- Transconductance

- Impedance at the electrode-tissue interface

- Signal-to-noise ratio for recording devices

- Correlate electrical performance metrics with histological outcomes from explanted devices.

- For sensing applications, measure analyte sensitivity and response time chronically to determine how fibrotic encapsulation affects device function [18] [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for FBR Investigation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Selenophene-based polymers | Semiconductor with immunomodulatory properties | Backbone engineering for reduced macrophage activation [18] |

| THP (Triazole-tetrahydropyran) | Immunomodulatory side chain | Side-chain functionalization to downregulate inflammatory biomarkers [18] |

| TMO (Triazole-thiomorpholine 1,1-dioxide) | Immunomodulatory side chain | Side-chain functionalization for enhanced FBR suppression [18] |

| EVADE Elastomers | Tetrahydropyran-based immunocompatible materials | Long-term implantable devices with minimal fibrosis [7] |

| Anti-CD68 antibodies | Macrophage identification | Immunofluorescence staining of immune cell infiltration [18] |

| Anti-α-SMA antibodies | Myofibroblast identification | Detection of activated fibroblasts in fibrotic capsule [3] |

| Masson's Trichrome stain | Collagen visualization | Histological assessment of fibrous encapsulation [18] [7] |

| S100A8/A9 inhibitors | Alarmin pathway blockade | Mechanistic studies of fibrosis pathway [7] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the single most important material property for reducing FBR in bioelectronic implants?

While there is no single solution, the mechanical mismatch between implant and tissue is a fundamental driver of FBR. Research consistently shows that matching the elastic modulus of the target tissue (typically 0.1-1 MPa for many soft tissues) significantly reduces chronic inflammation and fibrosis. However, an integrated approach combining appropriate stiffness with immunomodulatory chemistry and topography yields the best outcomes [7] [21].

Q2: How quickly does the foreign body response initiate after implantation?

The FBR cascade begins within seconds to minutes with protein adsorption on the material surface. Neutrophil recruitment peaks within the first 2 days, followed by monocyte infiltration and macrophage differentiation. The chronic inflammatory phase typically lasts about 3 weeks, with fibrous encapsulation becoming evident by 4 weeks and maturing over several months [3].

Q3: Can we completely prevent foreign body response, or only minimize it?

Current evidence suggests that FBR can be significantly minimized but not completely eliminated. Even the most biocompatible materials still initiate some degree of immune recognition. The research goal is to develop materials that steer the immune response toward tolerance and integration rather than attempting to completely evade immune detection [22] [7].

Q4: What are the most promising new strategies for FBR-resistant bioelectronics?

Emerging approaches include: (1) Selenophene-based semiconducting polymers that suppress macrophage activation; (2) Immunomodulatory side chains (THP, TMO) that actively downregulate inflammatory pathways; (3) EVADE-class elastomers enabling long-term implantation without significant fibrosis; and (4) Biomimetic topographies that discourage fibrotic cell adhesion [18] [7] [20].

Q5: How do I determine if my material's FBR performance is improved compared to standards?

Standardized assessment should include: (1) Quantification of capsule thickness and collagen density via histology (Masson's Trichrome); (2) Immune cell profiling (macrophages, myofibroblasts) via immunofluorescence; (3) Cytokine expression analysis of both pro- and anti-inflammatory markers; and (4) Functional assessment in relevant device configurations. A >50% reduction in collagen density with maintained or improved electrical performance indicates significant improvement [18] [7].

Engineering Solutions: Material and Design Strategies to Evade the Immune System

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core principle behind using selenophene backbones and immunomodulatory side chains in bioelectronic materials?

The core principle is to intrinsically design the material at a molecular level to actively suppress the foreign body response (FBR), rather than just being passively inert. This two-pronged approach incorporates selenophene into the polymer backbone to mitigate macrophage activation and adds immunomodulatory functional groups (like THP and TMO) to the side chains to downregulate the expression of inflammatory biomarkers. Together, these strategies aim to reduce chronic inflammation and subsequent fibrotic encapsulation, which can impair device function [14] [20] [17].

Q2: What quantitative improvements can be expected from these design strategies?

When implemented in a semiconducting polymer based on p(g2T-T), these immune-compatible designs have demonstrated substantial improvements in key performance metrics, as summarized below [14] [20]:

| Performance Metric | Improvement Achieved | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Foreign Body Response | Up to 68% reduction in collagen density [14] | Indicates significantly less fibrotic scar tissue formation around the implant. |

| Electrical Performance | Charge-carrier mobility of up to 1.2 cm² V⁻¹ s⁻¹ [14] [20] | Maintains high electrical conductivity necessary for bioelectronic device function. |

| Signal Fidelity | Higher signal amplitudes maintained after 4 weeks of implantation [20] | Ensures chronic recording quality for applications like electrocardiography (ECG). |

Q3: Why is suppressing the foreign body response (FBR) critical for implantable bioelectronics?

The FBR is an immune-mediated reaction that begins with protein adsorption on the implant and culminates in the formation of a dense, avascular collagen capsule. This fibrotic tissue acts as an insulating barrier, impeding intimate contact between the device and the tissue [3] [17]. For bioelectronics, this isolation hinders signal transmission (recording and stimulation), reduces the efficiency of drug delivery, and can ultimately lead to device failure. Mitigating FBR is therefore essential for achieving long-term stability and functionality of implantable devices [14] [3].

Q4: How do these molecular designs affect macrophage behavior?

Macrophages are key immune cells in the FBR cascade. The designed polymers work by suppressing macrophage activation. Comprehensive immunological assays have shown that these materials can downregulate pro-inflammatory biomarkers (often associated with the M1 macrophage phenotype) and upregulate anti-inflammatory biomarkers (associated with the M2 phenotype). This shift in macrophage polarization from a pro-inflammatory to a pro-healing state is a key mechanism for reducing the FBR [14] [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent Foreign Body Response Suppression In Vivo

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Variations in polymer synthesis leading to inconsistent incorporation of selenophene or immunomodulatory side chains.

- Solution: Implement rigorous characterization of each polymer batch using techniques like Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy to confirm molecular structure and ensure batch-to-batch consistency.

- Cause: Mechanical mismatch between the implant and the surrounding soft tissue, which can independently provoke an immune response.

- Solution: Tune the Young's modulus of the final device to better match the tissue (typically in the kPa to low MPa range). This can be achieved by adjusting the polymer composition or formulating it as a soft hydrogel composite [23].

- Cause: Inadequate sterilization of implants prior to surgery, introducing an external source of immune activation.

- Solution: Validate a sterilization protocol (e.g., ethylene oxide gas, sterile filtration) that does not degrade the polymer's electrical or immunomodulatory properties.

Issue 2: Poor Electrical Performance of the Synthesized Polymer

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Reduced crystallinity or π-conjugation length due to the incorporation of bulky side-chain groups.

- Solution: Optimize the ratio of immunomodulatory side chains to maintain a balance between biocompatibility and electronic transport. Techniques like grazing-incidence X-ray scattering (GIXS) can be used to assess the solid-state structure and crystallinity [14].

- Cause: Inadequate doping levels, leading to low charge carrier density.

- Solution: Re-optimize the doping process (e.g., using chemical or electrochemical methods) for the new polymer structure to enhance conductivity [23].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of Selenophene-Based Copolymer with Immunomodulatory Side Chains

This protocol outlines the synthesis of a semiconducting polymer with a selenophene backbone and tetrahydropyran (THP) functionalized side chains, adapted from recent literature [14] [7].

1. Reagents and Equipment:

- Monomer A: Selenophene-based dibromide monomer.

- Monomer B: Distannyl-functionalized comonomer bearing tetrahydropyran (THP) protected side chains.

- Catalyst: Tetrakis(triphenylphosphine)palladium(0) (Pd(PPh₃)₄).

- Solvent: Anhydrous toluene and anhydrous dimethylformamide (DMF).

- Reaction Environment: Schlenk line or glovebox for inert atmosphere (Ar/N₂).

- Purification: Methanol, acetone, Soxhlet extraction apparatus.

2. Step-by-Step Procedure: 1. Add Monomer A (0.5 mmol), Monomer B (0.5 mmol), and Pd(PPh₃)₄ (0.02 mmol) to a dry Schlenk tube inside a glovebox. 2. Evacuate and purge the tube with argon three times. 3. Add a 3:1 mixture of degassed anhydrous toluene and DMF (total volume 5 mL). 4. Heat the reaction mixture to 90-110 °C with stirring for 48-72 hours. 5. Allow the mixture to cool to room temperature. 6. Precipitate the polymer by slowly dripping the reaction mixture into vigorously stirred methanol (200 mL). 7. Collect the resulting fibrous solid via filtration. 8. Sequentially purify the polymer using a Soxhlet extractor with methanol (24 h) and acetone (24 h) to remove catalysts and oligomers. 9. Recover the final polymer by dissolving in a minimal amount of chloroform and re-precipitating in methanol. Dry the polymer under vacuum overnight.

Protocol 2: In Vivo Subcutaneous Implantation for FBR Assessment

1. Materials and Preparation:

- Polymer Films: Fabricate thin films of test and control polymers (e.g., thiophene-based analog) of standardized size and shape (e.g., 1x1 cm squares).

- Sterilization: Sterilize all films using ethylene oxide gas or exposure to UV light.

- Animal Model: C57BL/6 mice (8-12 weeks old).

2. Surgical Procedure: 1. Anesthetize the mouse according to your institution's animal care protocol. 2. Shave and disinfect the dorsal area. 3. Make a small midline incision and create subcutaneous pockets on each side of the incision using blunt dissection. 4. Implant one polymer film into each pocket, ensuring the test and control materials are randomized. 5. Close the incision with sutures or wound clips. 6. Administer post-operative analgesics and monitor animals until they fully recover.

3. Explanation and Analysis (After 4 Weeks): 1. Euthanize the animals and carefully excise the implant with the surrounding tissue. 2. Fix the tissue-implant construct in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24-48 hours. 3. Process the tissue for paraffin embedding and sectioning. 4. Perform histological staining: * Masson's Trichrome: To stain collagen fibers (fibrotic capsule) blue. * Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E): For general tissue morphology and immune cell infiltration. 5. Image the stained sections under a light microscope. 6. Quantify the FBR by measuring the thickness of the collagen capsule (in μm) and the density of collagen around the implant using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ) [14] [7].

Key Signaling Pathways in Foreign Body Response

The following diagram illustrates the key immune signaling pathways involved in the Foreign Body Response (FBR) and the points where selenophene backbones and immunomodulatory side chains are hypothesized to intervene.

Experimental Workflow for Material Evaluation

The diagram below outlines the core workflow for designing, synthesizing, and evaluating immunomodulatory semiconducting polymers.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and reagents used in the synthesis and evaluation of immunomodulatory semiconducting polymers.

| Item | Function / Role in Research | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Selenophene Monomers | Forms the core conjugated backbone of the polymer, providing electronic conductivity and intrinsic immunomodulatory properties by mitigating macrophage activation [14] [20]. | e.g., Selenophene-based dibromide or distannyl monomers. |

| Immunomodulatory Monomers | Introduces functional groups (e.g., THP, TMO) into polymer side chains to actively downregulate inflammatory biomarkers and suppress the FBR [14] [7]. | e.g., Monomers with tetrahydropyran (THP) ether groups. |

| Palladium Catalyst | Catalyzes key carbon-carbon coupling reactions (e.g., Stille or Suzuki polymerization) to form the conjugated polymer chain [14]. | e.g., Tetrakis(triphenylphosphine)palladium(0) (Pd(PPh₃)₄). |

| Organic Electrochemical Transistor (OECT) | A standard device architecture for evaluating the electrical performance (e.g., charge carrier mobility, transconductance) of semiconducting polymers in an electrolyte environment, mimicking biological conditions [14] [20]. | Custom-fabricated OECT devices. |

| Masson's Trichrome Stain | A histological stain used to visualize and quantify collagen deposition (fibrotic capsule) around explanted devices [14] [7]. | Standard histological staining kit. |

| Antibodies for Immunohistochemistry | Used to detect and visualize specific immune cell markers (e.g., CCR-7, TNF-α) and activation states in tissue sections surrounding the implant [7]. | e.g., Anti-CCR7, Anti-TNF-α, Anti-IL-6. |

This technical support center is designed for researchers and scientists working to minimize the Foreign Body Response (FBR) in implantable bioelectronics. The FBR—a complex cascade of inflammation, immune cell recruitment, and fibrotic encapsulation—severely compromises the long-term functionality of sensitive devices such as neural interfaces, continuous glucose monitors, and cochlear implants. This resource provides targeted troubleshooting guides, detailed experimental protocols, and FAQs focused on two primary strategies: engineering surface topographies with micro- and nano-scale features and applying non-fouling zwitterionic chemical coatings. The guidance herein is framed within the context of a doctoral thesis, aiming to bridge foundational research and practical, repeatable experimentation.

Troubleshooting Guides: Common Experimental Challenges

Zwitterionic Hydrogel Coating Application

Problem: Inconsistent or Non-Uniform Coating Coverage Observed as patchy coatings or areas where the coating delaminates from the substrate, particularly on complex geometries like electrode arrays.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Incorrect Surface Preparation.

- Solution: Ensure the substrate (e.g., PDMS) is thoroughly cleaned and activated. Use an oxygen plasma treatment immediately prior to coating application to ensure high surface energy and reactivity [24].

- Cause 2: Sub-Optimal Photografting Parameters.

- Cause 3: Inadequate Coating Solution Formulation.

- Solution: Confirm the purity of the zwitterionic monomer (e.g., CBMA) and ensure it is freshly dissolved. Filter the solution to remove any particulates that could cause defects.

- Cause 1: Incorrect Surface Preparation.

Problem: Loss of Anti-Fouling Properties After Implantation The coating appears intact but shows increased protein adsorption or cellular adhesion in in-vivo tests compared to initial in-vitro results.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Hydrogel Degradation or Mechanical Failure.

- Cause 2: Hydrogel Dehydration or Handling Damage.

- Solution: Always store and handle coated devices in an aqueous solution (e.g., PBS) to prevent dehydration-induced cracking. Develop specialized fixtures for implantation to minimize physical contact with the coated surface.

Micro/Nano-Patterning of Substrates

Problem: Poor Cell Adhesion or Misaligned Morphology on Micro-Patterns Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) or other target cells fail to adhere, or their morphology does not align with the intended topographic cues.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Inadequate Protein Pre-adsorption.

- Solution: Pre-incubate the patterned substrate in cell culture medium or a relevant protein solution (e.g., serum) immediately after oxygen plasma treatment. Surface hydrophilicity and protein adsorption capacity can decay over time when stored in air [26].

- Cause 2: Pattern Dimensions are Non-Optimal.

- Solution: Redesign the pattern based on literature values. For instance, micro-gratings or pillars with an aspect ratio of 1:2 and an interspace of 2 μm have been successfully used to guide MSC orientation and migration [26].

- Cause 3: Contamination of the Pattern.

- Solution: Implement rigorous cleaning protocols post-fabrication, using solvents and techniques that do not damage the delicate micro/nano-features.

- Cause 1: Inadequate Protein Pre-adsorption.

Problem: Insufficient Bactericidal Effect of Nanotopographies Gram-negative (E. coli) or gram-positive (S. aureus) bacteria continue to colonize nanostructured surfaces.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Nanofeature Dimensions are Incorrect.

- Solution: Ensure the nanofeatures (e.g., Moth-Eye nanocones) have sharp tips and a height/spacing that generates sufficient mechanical stress to rupture bacterial membranes upon contact. Features with contact points in the 10–100 nm range are typically required [26].

- Cause 2: Material Stiffness is Too Low.

- Solution: The mechano-bactericidal effect requires the substrate to be sufficiently rigid to prevent deformation when bacteria attach. Consider using hard PDMS (hPDMS) or PMMA instead of soft elastomers for the nanostructured layer [26].

- Cause 1: Nanofeature Dimensions are Incorrect.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary mechanism by which zwitterionic hydrogels reduce the FBR? A1: Zwitterionic polymers, such as pCBMA, create a dense, highly ordered hydration layer via their paired positive and negative charges. This layer forms a physical and energetic barrier that significantly reduces the initial, non-specific adsorption of proteins (e.g., fibrinogen). Since protein fouling is the first step in the FBR cascade, its suppression leads to reduced macrophage adhesion, foreign body giant cell formation, and ultimately, a thinner fibrotic capsule [25] [24].

Q2: Can surface topography and chemistry strategies be combined? A2: Yes, and this is a leading-edge approach. Hierarchical surfaces that combine microtopographies (to guide host cell integration) with nanotopographies (for bactericidal effects) can be further enhanced with a zwitterionic coating. This multi-scale strategy simultaneously addresses multiple aspects of the FBR: preventing infection, directing desirable cell responses, and minimizing non-specific protein fouling [26].

Q3: How do I validate the in-vivo performance of my modified surface? A3: Beyond standard in-vitro fouling tests, subcutaneous implantation in rodent models is a common and effective validation step. Key quantitative endpoints include:

- Histomorphometry: Measure the fibrotic capsule thickness around the implant after explantation. A successful coating can reduce thickness by 50-70% compared to uncoated controls [25] [24].

- Immunohistochemistry: Stain tissue sections for specific cell markers (e.g., CD68 for macrophages, α-SMA for myofibroblasts) to qualitatively and quantitatively assess the cellular immune response.

- Functional Testing: For drug-delivery devices, measure the transport of a model drug (e.g., insulin) over time to demonstrate that the modification maintains functional efficacy [27].

Q4: My coating is stable in buffer but fails in vivo. What could be wrong? A4: The in-vivo environment is far more challenging. This failure often points to a lack of mechanical durability. The coating may be degrading, or more likely, it is being physically compromised by the compressive and shear forces exerted by the surrounding tissue and immune cells. Solutions include optimizing the cross-linking density and testing the coated device in a simulated biological mechanical environment before moving to in-vivo studies.

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from recent literature to aid in experimental design and benchmarking.

Table 1: In-Vivo Performance of Zwitterionic pCBMA Coatings

| Metric | Performance Data | Experimental Conditions | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fibrotic Capsule Thickness Reduction | 50 - 70% | Coated vs. uncoated PDMS sheets & cochlear implants; 6 wk - 1 yr implantation in mice | [25] [24] |

| Effective Cross-linker Composition | 5 - 50 wt% | pCBMA coatings with varying PEGDMA cross-linker; maintained anti-fouling properties | [25] [24] |

| Coating Durability | > 6 months | No degradation or loss of anti-fouling function after subcutaneous implantation | [25] |

Table 2: Design Parameters for Differential Biological Responses via Topography

| Biological Target | Topography Type | Typical Feature Dimensions | Observed Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria (E. coli, S. aureus) | Moth-Eye (ME) Nanocones | Nanoscale sharp tips (10-100 nm contact points) | Mechano-bactericidal effect; bacteria membrane rupture | [26] |

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Low Aspect Ratio (LAR) Micropillars/Gratings | 1:2 aspect ratio (height:diameter), 2 μm interspace | Influenced cell orientation, migration, and enhanced osteogenic marker expression | [26] |

| Combined Strategy | Hierarchical (LAR + ME) | Micro-features (as above) fully covered with ME nanocones | Maintained cytocompatibility with MSCs while retaining bactericidal effect | [26] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Photografting Zwitterionic Hydrogel onto PDMS

This protocol details the simultaneous photopolymerization and photografting of poly(carboxybetaine methacrylate) - pCBMA onto PDMS substrates, a key methodology for creating durable anti-fouling coatings [24].

I. Materials

- Substrate: Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) sheets or device.

- Monomer: (3-([2-(Methacryloyloxy)ethyl]-dimethylammonio)propionate (CBMA).

- Cross-linker: Poly(ethylene glycol) dimethacrylate (PEGDMA, MW 750 Da).

- Photo-initiator: Irgacure 2959.

- Solvent: Deionized water.

- Equipment: UV Light Source (~320–390 nm wavelength), Oxygen Plasma Cleaner, Vacuum Desiccator.

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Substrate Preparation: Clean PDMS substrates with sequential sonication in acetone, ethanol, and deionized water. Dry with nitrogen gas.

- Surface Activation: Treat the clean PDMS surfaces with oxygen plasma for 1-2 minutes to generate surface-reactive radicals.

- Coating Solution Preparation: In deionized water, prepare a solution containing:

- 1.0 M CBMA monomer.

- 5-50 wt% PEGDMA cross-linker (relative to monomer).

- 1.0 mM Irgacure 2959 photo-initiator.

- Dissolve completely and degas the solution using a vacuum desiccator to remove oxygen, which inhibits free-radical polymerization.

- Coating Application: Pipette the coating solution onto the activated PDMS surface, ensuring complete coverage.

- Photografting & Polymerization: Immediately place the sample under the UV lamp. Irradiate for 5-10 minutes in an inert atmosphere (e.g., under a nitrogen purge). This step simultaneously grafts the polymer network to the PDMS surface and cross-links the hydrogel.

- Post-Processing: Rinse the coated substrate thoroughly with copious amounts of sterile PBS or deionized water to remove any unreacted monomers and photo-initiator. Store hydrated until use.

III. Validation and QC Checks

- Water Contact Angle: A significant decrease in the contact angle (superhydrophilic surface) indicates successful coating application.

- In-Vitro Fouling Test: Immerse the coated substrate in a solution of fluorescently tagged fibrinogen (1 mg/mL) for 1 hour. Image using fluorescence microscopy. A successful coating will show minimal protein adsorption compared to an uncoated control.

Protocol: Creating Hierarchical Micro-Nano Topographies

This protocol outlines the process for fabricating hierarchical surfaces with micro-gratings/pillars and Moth-Eye nanocones to differentially control MSC and bacterial responses [26].

I. Materials

- Polymers: PMMA or hPDMS (hard PDMS).

- Master Templates: Silicon wafers with patterned micro- and nano-features fabricated via electron-beam or photolithography.

- Equipment: Oxygen Plasma Reactor, Soft Lithography Setup, Spin Coater.

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Master Fabrication (or sourcing): Obtain or fabricate a silicon master wafer containing the desired hierarchical negative pattern (e.g., micro-gratings covered with nanoconces).

- Replica Molding:

- For PMMA: Use a thermal nanoimprinting process. Heat the PMMA above its glass transition temperature and press it onto the master wafer under controlled pressure.

- For hPDMS: Mix the hPDMS prepolymer and pour it over the master wafer. Cure at elevated temperature (e.g., 65°C for 1 hour).

- Demolding: Carefully peel the solidified polymer replica from the master wafer.

- Surface Activation for Cell Culture: Immediately before cell seeding, treat the topographic substrates with oxygen plasma for ~1 minute to render them temporarily hydrophilic.

- Protein Pre-conditioning: Without delay, incubate the plasma-treated substrates in the complete cell culture medium for at least 1-5 hours to allow for the formation of a protein conditioning layer that promotes cell adhesion.

III. Validation and QC Checks

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): Image the fabricated surfaces to verify the fidelity and integrity of the micro- and nano-features.

- Water Contact Angle (WCA): Measure the WCA before and after plasma treatment to confirm increased hydrophilicity.

- Bactericidal Assay: Incubate the substrates with a known concentration of E. coli or S. aureus for several hours, then perform live/dead staining and plate counting to quantify bacterial viability.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Workflow for Coating Development and Validation

This diagram illustrates the end-to-end workflow for developing and validating a zwitterionic surface coating, from initial synthesis to final in-vivo assessment.

Diagram 1: Workflow for developing and validating a surface coating to minimize the Foreign Body Response (FBR), integrating both in-vitro and in-vivo stages.

Host Immune Response and Modification Strategies

This diagram maps the key biological stages of the Foreign Body Response (FBR) and aligns them with the strategic interventions provided by surface modifications.

Diagram 2: The Foreign Body Response cascade and strategic intervention points for surface modifications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for FBR-Mitigating Surface Research

| Category | Item / Reagent | Primary Function in Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zwitterionic Chemistry | Carboxybetaine Methacrylate (CBMA) Monomer | Primary building block for creating ultra-low-fouling hydrogel coatings. | Purity is critical for consistent polymerization and performance. |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) dimethacrylate (PEGDMA) | Cross-linker to create a robust, stable hydrogel network from CBMA. | Molecular weight (e.g., 750 Da) and concentration (5-50 wt%) affect mesh size and stiffness. | |

| Irgacure 2959 | Photo-initiator to generate free radicals for the UV-induced grafting and polymerization process. | Must be soluble in aqueous solutions; concentration impacts initiation rate. | |

| Substrate Materials | Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | A common, biocompatible elastomer used for device housing (e.g., cochlear implants). | Requires surface activation (plasma) for covalent coating attachment. |

| Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) | A rigid thermoplastic used for creating micro/nano-topographies via nanoimprinting. | Offers high stiffness, which is beneficial for mechano-bactericidal effects. | |

| Biological Assays | Fibrinogen, fluorescently tagged | Model protein for in-vitro anti-fouling validation assays. | A significant reduction in adsorption indicates a successful coating. |

| Primary Macrophages or cell lines (e.g., RAW 264.7) | Used for in-vitro assessment of the cellular inflammatory response. | Look for reduced adhesion and altered morphology on modified surfaces. | |

| Specific Antibodies (e.g., anti-CD68, anti-α-SMA) | For immunohistochemical staining of immune cells and fibroblasts in explanted tissue. | Allows quantification of the FBR in-vivo. |

Technical Support Center: FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

This technical support center provides practical guidance for researchers developing soft, tissue-like electronics to minimize Foreign Body Response (FBR). The FAQs and protocols below address common experimental challenges within the context of bioelectronics and regenerative engineering.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is mechanical mismatch a critical problem in bioelectronic implants? The pronounced mechanical mismatch between rigid conventional implants (e.g., silicon, ~180 GPa) and soft neural tissue (~1–30 kPa) prevents devices from conforming to biological substrates. This leads to physical damage during insertion, exacerbates tissue micromotion, and triggers a severe foreign body response (FBR), resulting in inflammation, glial scar encapsulation, and eventual signal degradation [28] [6].

Q2: What are the primary material strategies for achieving tissue-like softness? Strategies can be categorized into three main approaches:

- Soft Polymers and Elastomers: Use of materials like polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), polyimide (PI), and thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) as substrates or encapsulation [28] [13].

- Conductive Composites: Combining soft polymers with conductive fillers like carbon nanotubes, graphene, or conductive polymers (e.g., PEDOT:PSS) to create flexible conductive traces [28] [29].

- Hydrogels: Using hydrogels based on materials such as poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) (pHEMA), alginate, or gelatin, which closely mimic the hydrated environment of native tissues [3] [30].

Q3: How does surface topography influence the Foreign Body Response? Surface topography at the micro/nano level regulates protein adsorption and immune cell interaction. For instance, engineered surface roughness or specific porosity (e.g., pHEMA scaffolds with 34 μm porosity) can reduce the density of the fibrous capsule, decrease macrophage attachment, and increase local vascularization, thereby mitigating the FBR [3].

Q4: We are experiencing inconsistent cell viability when bioprinting with multiple materials. What could be the cause? Inconsistent viability in multi-material bioprinting often stems from crosslinking incompatibility or handling protocols. Different bioinks have specific, and sometimes conflicting, requirements for temperature, pH, or crosslinking agents. Ensure that the crosslinking method for one material does not adversely affect the cell-laden counterpart and rigorously standardize mixing and handling protocols across all batches [30].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Chronic Inflammatory Response and Fibrous Encapsulation In Vivo

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Excessive mechanical stiffness | Measure the elastic modulus of your construct and compare it to the target tissue (typically 1-100 kPa) [29]. | Transition to softer substrates (e.g., PDMS, SEBS) or use ultra-thin, flexible geometric designs (e.g., serpentine wires, mesh structures) to reduce flexural rigidity [28] [29]. |

| Bio-incompatible material surface | Perform in vitro cytotoxicity and cell adhesion assays using relevant cell lines (e.g., neurons, fibroblasts) [13]. | Select polymers with proven biocompatibility (e.g., Polyimide, PDMS) or apply bioactive surface coatings (e.g., with extracellular matrix proteins) to improve integration [28] [13]. |

Problem 2: High Electrode Impedance and Poor Signal-to-Noise Ratio

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient conductive surface area | Perform electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) on fabricated electrodes. | Coat metal electrodes (e.g., Pt, Au) with conductive polymers like PEDOT:PSS or polypyrrole (PPy), which significantly reduce impedance and enhance charge injection capacity [28] [29]. |