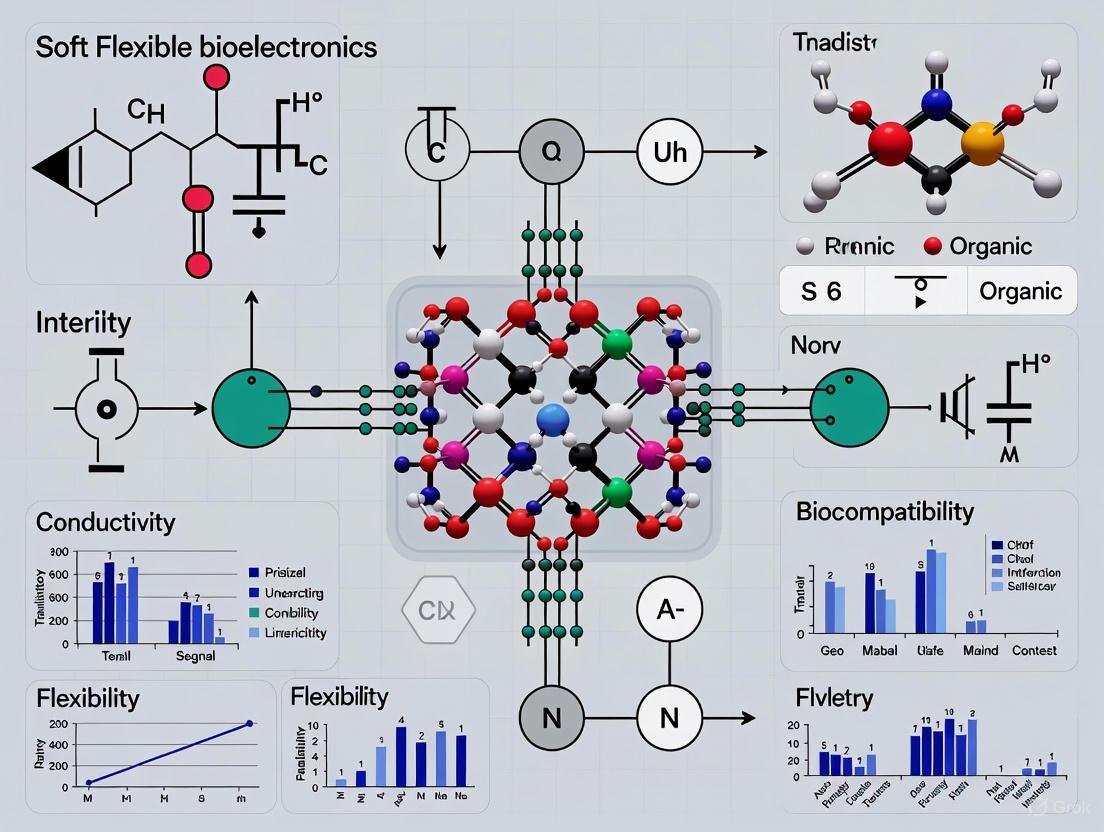

Soft and Flexible Bioelectronics: Materials Design, Clinical Applications, and Future Directions for Advanced Healthcare

This article provides a comprehensive review of the latest advancements in soft and flexible bioelectronic materials, a field poised to revolutionize digital healthcare and biomedical research.

Soft and Flexible Bioelectronics: Materials Design, Clinical Applications, and Future Directions for Advanced Healthcare

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive review of the latest advancements in soft and flexible bioelectronic materials, a field poised to revolutionize digital healthcare and biomedical research. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of tissue-like electronics designed to overcome the mechanical mismatch with biological systems. The scope spans from novel material designs—including hydrogels, liquid metals, and conductive polymers—to their fabrication and integration into wearable and implantable devices for continuous health monitoring and closed-loop therapeutic interventions. Further, it delves into critical challenges such as long-term stability, signal fidelity, and biocompatibility, offering troubleshooting and optimization strategies. Finally, the article presents a comparative analysis of material performance and validation frameworks essential for clinical translation, synthesizing key takeaways to outline a future roadmap for the field.

The Foundation of Soft Bioelectronics: Overcoming the Mechanical Mismatch with Biological Tissues

The development of bioelectronic devices for medical applications is fundamentally constrained by a pervasive biomechanical incompatibility: the rigid, static nature of conventional electronics is a poor match for the soft, dynamic, and water-rich environment of human tissues. This mechanical mismatch can lead to inaccurate signal acquisition, tissue damage, chronic inflammation, and device failure [1] [2]. This whitepaper delineates the core principles of this challenge, details emerging solutions centered on soft materials and innovative fabrication techniques, and provides a technical overview of the experimental methodologies and reagent solutions driving the field of soft bioelectronics forward. The content is framed within a broader thesis that overcoming this mechanical mismatch is paramount for the next generation of seamless, biocompatible human-machine interfaces.

Living tissues are soft, elastic, and constantly in motion—from the pulsations of the heart and brain to the subtle shifts of skin and muscle. The mechanical properties of these tissues, such as Young's modulus (a measure of stiffness), are typically in the kilopascal (kPa) to megapascal (MPa) range [3] [4]. In stark contrast, the silicon and metals that form the backbone of conventional electronics are rigid and brittle, with Young's moduli orders of magnitude higher (in the gigapascal, GPa, range). This stark difference creates a fundamental incompatibility at the bio-electronic interface.

When a rigid device is implanted or attached to soft tissue, the resulting mechanical mismatch can cause several critical issues:

- Reduced Treatment Effectiveness: Unstable contact leads to motion artifacts and unreliable data [1] [5].

- Tissue Damage: The persistent rubbing and pressure from a rigid device can damage delicate cellular structures [1].

- Chronic Immune Response: The body recognizes the rigid device as a foreign body, triggering inflammation and fibrotic encapsulation, which can isolate the device and degrade its performance over time [2] [6].

- Device Failure: The inability of a rigid device to withstand repeated stretching and bending can lead to mechanical fracture and electronic failure [5].

The following table quantifies the mechanical properties of various biological tissues and conventional electronic materials, illustrating the core of the challenge.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Mechanical Properties between Soft Tissues and Conventional Electronics

| Material / Tissue | Young's Modulus | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Human Soft Tissues | ||

| Human Normal Liver | ~10 kPa [3] | Soft, easily deformable |

| Human Diseased Liver | ~52 kPa [3] | Stiffer than healthy tissue |

| Breast Benign Lesion | ~146 kPa [3] | Moderately stiff |

| Breast Malignant Lesion | ~270 kPa [3] | Significantly stiffer |

| Articular Cartilage | ~0.7 - 1 MPa [3] | Resilient, load-bearing |

| Conventional Electronics | ||

| Silicon (Si) | ~130 - 190 GPa [2] | Rigid, brittle |

| Gold (Au) | ~78 GPa | Dense, malleable but not stretchable |

| Copper (Cu) | ~110 - 128 GPa | High conductivity, rigid |

Experimental Methodologies for Characterization and Validation

Overcoming the mechanical mismatch requires a deep understanding of both the tissue's properties and the device's performance under realistic conditions. The following sections describe key experimental protocols used in the field.

Protocol: Water Jet Indentation for Soft Tissue Modulus Characterization

This non-contact method is used to quantitatively image the elastic modulus of soft tissues with high resolution [3].

1. Principle: A jet of water serves as a soft indenter to deform the tissue, while high-frequency ultrasound (e.g., 50 MHz) propagating through the same water jet simultaneously measures the resulting tissue deformation and thickness.

2. Experimental Setup:

- Apparatus: A 3D translating device holds a water container connected via a pressure sensor to a nozzle and an ultrasound transducer.

- Key Parameters: Nozzle diameter (e.g., 1.7 mm), distance from nozzle to tissue (e.g., 0.95 mm), water flow speed (1-10 m/s).

3. Procedure:

- The water jet is focused on the tissue surface using the 3D translator.

- The pressure sensor records the indentation force (F), while ultrasound measures the indentation depth (d) and tissue thickness (h).

- The system performs a C-scan to obtain a modulus map of the region of interest.

4. Data Analysis - Improved Hayes' Equation:

Young's modulus (E) is calculated using a finite element (FE)-validated improvement of Hayes' equation:

E = (1 - v²) / (2a * k(v, a/h, d/h)) * (F/d)

where v is Poisson's ratio, a is the indenter radius, and k is a scaling factor dependent on v, aspect ratio (a/h), and deformation ratio (d/h). This model allows quantitative evaluation of E with an error of no more than 2% [3].

Protocol: In Vivo Performance Testing of Stretchable Bioelectronic Devices

This protocol validates the functionality and biocompatibility of novel soft devices in biologically relevant environments [1] [5].

1. Device Fabrication:

- Liquid Metal-Based Electronics: A combination of colloidal self-assembly and micro-transfer printing is used to pattern liquid metal particles (e.g., gallium-based alloys) with micrometer-scale resolution onto stretchable substrates, creating electronics that can withstand over 1,200% stretching [1].

- Organic Electrochemical Transistors (OECTs): Asymmetric transistors are fabricated from a single, biocompatible organic polymer material that interacts with biological ions. This simplifies fabrication and enhances biocompatibility [5].

2. Functional Testing:

- Strain Sensing: Devices are subjected to controlled, large deformations to validate the reliability of electrical conductivity and sensing accuracy under extreme stretching.

- Cardiac Electrophysiological Mapping: Instrumented balloon catheters with liquid metal microelectrode arrays are inflated inside explanted human hearts or animal models. Electrical impedance and the ability to acquire high-resolution maps of cardiac electrical activity are measured [1].

- Chronic Neural Recording: Soft transistor-based sensor implants are placed on the brain of developing animals. The quality of acquired neural signals is monitored over time to assess the device's ability to maintain a stable bio-interface through tissue growth and structural changes [5].

3. Biocompatibility Assessment:

- Histological analysis is performed on the surrounding tissue after a predetermined implantation period to check for signs of inflammation or fibrosis compared to controls with rigid implants.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The advancement of soft bioelectronics relies on a specific set of material solutions designed to bridge the mechanical and chemical divide with biological systems.

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Soft Bioelectronics Research

| Reagent / Material | Function and Rationale |

|---|---|

| Liquid Metal Alloys (e.g., EGaIn) | Serves as a highly conductive yet deformable interconnect and electrode material; enables extreme stretchability (>1200%) while maintaining electrical function [1]. |

| Conductive Organic Polymers (e.g., PEDOT:PSS) | Provides a mixed ionic-electronic conductivity, facilitating efficient communication with biological systems (which use ions); is inherently softer and more biocompatible than inorganic semiconductors [2] [5]. |

| Functionalized Hydrogels | Acts as a hydrated, porous, and tissue-like scaffold/encapsulation; allows diffusion of biomolecules and drugs, enhancing biosensing and therapeutic functions [6]. |

| Stretchable Conductive Nanocomposites | Combines conductive nanomaterials (e.g., metal nanowires, graphene) with elastic polymers (e.g., PDMS); creates a percolation network that maintains conductivity under strain [2]. |

| Hydrogel Semiconductors | A nascent class of materials that are both semiconductor and hydrogel simultaneously; provides tissue-like mechanical properties (softness, hydration) with semiconductive ability, enabling intimate biointerfaces with augmented sensing and photo-modulation effects [6]. |

Visualizing the Development Workflow for Soft Bioelectronics

The following diagram synthesizes the logical workflow and key decision points in developing a solution to the mechanical mismatch challenge, from problem identification to functional application.

The evolution of soft and flexible bioelectronics represents a paradigm shift in the interface between artificial devices and biological systems. The fundamental challenge in this field stems from the profound mechanical mismatch between conventional rigid, planar electronics and the soft, curvilinear, and dynamic structures of biological tissues. This mechanical disparity can lead to inaccurate signal acquisition, tissue damage, and chronic inflammatory responses, ultimately causing device failure [7]. To overcome these limitations, a new class of electronic materials has emerged, defined by three core properties: stretchability, the ability to withstand mechanical deformation without functional degradation; conformability, the capacity to form stable, intimate contact with irregular biological surfaces; and tissue-mimicking softness, the replication of the low elastic modulus characteristic of biological tissues. This technical guide delineates the definitions, measurement methodologies, and material strategies for achieving these essential properties, providing a framework for the next generation of biointegrated devices.

Quantitative Definitions and Material Targets

For researchers, establishing clear quantitative targets is the first step in material selection and device design. The following tables summarize the key mechanical properties of biological tissues and the performance targets for bioelectronic materials.

Table 1: Mechanical Properties of Biological Tissues and Conventional Materials

| Material/Tissue | Young's Modulus | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Myocardial Tissue | 10-15 kPa [7] | Represents a key target for cardiac implants. |

| Soft Bio-tissues | ~10 kPa [8] | General modulus for many internal organs and soft structures. |

| Human Skin | Varies by region and layer | Dynamic, curvilinear, and anisotropic. |

| Conventional Elastomers (e.g., PDMS, SEBS) | ~1-3 MPa [8] | 2-3 orders of magnitude stiffer than soft tissues. |

| Stretchable Electronic Materials (conductors, semiconductors) | >100 MPa [8] | Intrinsically high modulus necessitates novel softening strategies. |

| Bulk Silicon | ~100 GPa [7] | The basis of traditional electronics, fundamentally mismatched with biology. |

Table 2: Target Properties for Bioelectronic Materials and Devices

| Property | Target Value / Performance Metric | Application Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Effective Device Modulus | < 10 kPa [8] | Achieves tissue-level softness for minimized mechanical mismatch. |

| Interfacial Toughness | > 100 J m⁻² [8] | Ensures strong adhesion between device layers and to tissue. |

| Stretchability | > 100% strain without electrical/functional failure [8] | Withstands dynamic movement of organs and skin. |

| Device Thickness | < 5 μm for conformability [9] | Ultralow bending stiffness for van der Waals-driven adhesion to skin. |

Material Strategies and Experimental Methodologies

Achieving Tissue-Mimicking Softness

While material synthesis has produced softer conductors and semiconductors, a powerful generalizable strategy is the soft interlayer design [8]. This approach allows the use of existing high-performance (but relatively high-modulus) stretchable materials by engineering the mechanical structure of the device.

- Working Principle: A thin soft interlayer with an intermediate modulus is inserted between the functional electronic film (e.g., semiconductor) and an ultrasoft substrate (e.g., hydrogel). This interlayer reduces stress concentration at defect sites in the functional layer during stretching, dramatically improving its effective stretchability.

- Validated Material System:

- Functional Layer: DPPT-TT/SEBS polymer semiconductor (modulus: 19.4 MPa).

- Soft Interlayer: SEBS H1052 (modulus: 2.83 MPa).

- Ultrasoft Substrate: Ecoflex-0010 (modulus: 55 kPa) or Polyacrylamide (PAAm) hydrogel.

- Critical Design Parameters:

- Interlayer Modulus: Should be within three orders of magnitude of the functional layer.

- Interlayer Thickness: At least ten times thicker than the functional layer (e.g., 200 nm to 2 μm for a semiconductor film).

- Adhesion: Interfacial toughness should exceed 100 J m⁻².

Measuring and Ensuring Conformability

Conformability is governed by a device's bending stiffness and its adhesion to the biological surface. A key metric is the bending stiffness (D), calculated as D = Eh³ / (12(1-ν²)), where E is the elastic modulus, h is the thickness, and ν is the Poisson's ratio.

- Strategy: To achieve conformal contact on skin, devices must be engineered to be ultrathin and flexible, minimizing bending stiffness. This allows for van der Waals-driven adhesion without external adhesives [9].

- Experimental Validation:

- Method: Finite-element analysis (FEA) simulating device attachment to a rough, curved surface.

- Measurement: 180° peeling tests to quantify interfacial toughness and adhesion energy between device layers and to model biological surfaces [8].

Engineering Intrinsic Stretchability

Stretchability can be imparted through a combination of material-level and structure-level engineering.

- Intrinsically Stretchable Materials:

- Structural Engineering:

- Architectural Designs: Employing serpentine mesh layouts, kirigami/origami patterns, and horseshoe shapes to allow the device to accommodate strain through out-of-plane deformation rather than material stretching [7] [11].

- Neutral Mechanical Plane Design: Placing stiff, brittle electronic components at the neutral mechanical plane within a soft encapsulation matrix to minimize strain on these components during bending [9].

Experimental Protocols for Characterization

Protocol: Finite-Element Analysis of a Soft Interlayer Design

This FEA protocol validates the mechanical function of a soft interlayer before fabrication.

- Model Setup: Create a three-layer 2D model representing the functional film, soft interlayer, and ultrasoft substrate.

- Introduce Defect: Incorporate a notch (pre-crack) into the functional film to study stress concentration.

- Apply Boundary Conditions: Fix one end of the model and apply a uniaxial tensile strain (e.g., 100%) to the other end.

- Parameter Sweep:

- Modulus: Vary the Young's modulus of the interlayer from MPa to GPa ranges.

- Thickness: Vary the interlayer thickness from nanometers to micrometers.

- Adhesion: Model different levels of delamination (poor adhesion) around the notch.

- Output Analysis: Map the principal stress and strain energy density at the notch tip. A successful design shows a significant reduction in these stress concentration metrics compared to a no-interlayer structure [8].

Protocol: Mechanical and Electrical Characterization under Strain

This experiment quantifies the stretchability and softness of a functional electronic material or device.

- Sample Preparation: Fabricate the thin-film material or device (e.g., transistor, conductor) on the target soft substrate with the designed interlayer.

- Mounting: Clamp the sample onto a uniaxial tensile stage.

- In-Situ Measurement:

- Mechanical: Apply incremental strain steps (e.g., 10% steps up to 100% strain). Use an optical microscope or digital image correlation (DIC) at each step to record crack density and propagation.

- Electrical: Simultaneously measure the key electrical property (e.g., conductivity for a conductor, charge-carrier mobility for a semiconductor transistor) at each strain step.

- Data Analysis: Plot electrical performance versus applied strain. The strain value at which the performance degrades by a predefined threshold (e.g., 50%) defines the functional stretchability of the device [8].

Diagram 1: Workflow for FEA of a soft interlayer design.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Soft Bioelectronics Research

| Category | Material / Reagent | Function / Key Property | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substrates & Encapsulation | Polyacrylamide (PAAm) Hydrogel | Ultrasoft substrate (modulus ~kPa). | Achieving tissue-level effective modulus [8]. |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | Conventional elastomer substrate (modulus ~MPa). | Flexible, but not tissue-soft, substrate [7]. | |

| Parylene-C | Biostable, ultrathin encapsulation/substrate. | Flexible OECTs for ECG sensing [9]. | |

| Interlayer Materials | SEBS H1052 | General-purpose soft interlayer (modulus 2.83 MPa, high adhesion). | Enabling stretchable semiconductors on ultrasoft substrates [8]. |

| Conductors | PEDOT:PSS/PFI blend | Stretchable transparent conductor. | Electrodes for biosignal recording [8] [9]. |

| Carbon Nanotube (CNT) assembly | Stretchable conductor network. | Gate, drain, and source electrodes in transistors [8]. | |

| Silver Nanowire (AgNW) | Stretchable conductor, high conductivity. | Transparent electrodes for OECTs [8] [9]. | |

| Semiconductors | DPPT-TT/SEBS blend | Stretchable polymer semiconductor. | Channel material in ultrasoft transistors [8]. |

| Characterization Tools | Peeling Test Stage | Quantifies interfacial toughness (J m⁻²). | Measuring adhesion strength between device layers [8]. |

| Tensile Stage with Microscope | Measures crack propagation under strain. | Characterizing functional stretchability [8]. |

Diagram 2: Core characterization methods for key material properties.

The convergence of stretchability, conformability, and tissue-mimicking softness is redefining the possibilities for biointegrated electronics. Moving beyond simple flexibility, the field now prioritizes an ultralow modulus to achieve seamless and stable integration with biological systems. The material strategies and experimental frameworks outlined in this guide—centered on the soft interlayer design, intrinsically stretchable composites, and ultrathin architectures—provide a foundational toolkit for researchers. The future trajectory of this field points toward the development of fully biodegradable and bioactive material systems that not only match the passive mechanics of tissue but also actively participate in biological signaling and self-repair processes [12] [7]. By adhering to the quantitative targets and rigorous characterization protocols defined herein, scientists can accelerate the development of next-generation bioelectronics for advanced diagnostics, therapeutics, and a truly symbiotic human-machine interface.

The emergence of soft and flexible bioelectronics represents a paradigm shift in the development of medical devices, diagnostic tools, and therapeutic systems. Traditional rigid electronic components face significant challenges in interfacing with biological tissues, which are inherently soft, dynamic, and aqueous. This mismatch in mechanical properties often leads to poor contact, signal interference, low signal conversion efficiency, and inflammatory responses [13]. Within this context, three key material classes—hydrogels, liquid metals, and conductive polymers—have emerged as foundational elements for next-generation bioelectronic interfaces.

These materials collectively address the critical need for mechanical compatibility with biological systems while maintaining excellent electronic functionality. Hydrogels provide tissue-like softness and biocompatibility, liquid metals offer unparalleled stretchability and self-healing capabilities, and conductive polymers bridge the gap between organic electronics and biological interfaces. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these three material classes, focusing on their fundamental properties, synthesis methodologies, and applications in soft bioelectronics, with particular emphasis on their roles in biomedical research and drug development.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Key Material Classes in Soft Bioelectronics

| Material Class | Key Properties | Primary Strengths | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogels | Tissue-like softness, high water content, biocompatibility, tunable mechanical properties [14] [15] | Excellent biocompatibility, permeable to biomolecules, customizable physical properties | Low electrical conductivity (pristine), mechanical fragility, environmental instability [16] |

| Liquid Metals | Fluidic nature, high electrical (3.4×10⁶ S/m) and thermal conductivity, stretchability, self-healing [17] | Extreme deformability (>1000% strain), negligible fatigue, shape reconfigurability | Surface oxidation challenges, difficult patterning/packaging, long-term stability concerns [18] |

| Conductive Polymers | Conjugated backbone, tunable conductivity, mechanical flexibility, redox activity [19] | Chemical diversity, processability, biocompatible formulations, controllable morphology | Limited environmental/electrical stability, mechanical rigidity, processing difficulties [19] |

Hydrogels

Fundamental Properties and Classification

Hydrogels are three-dimensional, cross-linked networks of hydrophilic polymers that can absorb significant amounts of water or biological fluids without dissolving [15]. Their structure and properties are influenced by polymer composition and cross-linking methods, resulting in a diverse range of characteristics including tunable swelling/deswelling behavior, multifunctional stimuli-responsiveness, and adjustable mechanical performance [14]. The high water content of hydrogels imparts both solid and fluid mechanical characteristics, with elastic moduli comparable to those of biological tissues, thus enhancing their biocompatibility and offering significant potential for biomedical applications [14].

Based on their cross-linking mechanisms, hydrogels are classified into several categories:

- Physically cross-linked: Rely on non-covalent interactions (electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions) [14]

- Chemically cross-linked: Involve covalent bond formation between polymer chains [14]

- Hybrid cross-linked: Combine physical and chemical cross-linking mechanisms [14]

According to their origin, hydrogel materials can be further categorized as:

- Synthetic polymers: Polyacrylamide (PAAm), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polyethylene glycol (PEG) [16]

- Natural polymers: Chitosan, agar, fibrin, proteins, polysaccharides [15]

Performance Characteristics and Measurement

The swelling behavior of hydrogels is a critical property determined by their hydrophilic functional groups and cross-linking density. The equilibrium swelling ratio is calculated as:

[ \text{Swelling Ratio} = \frac{Ws - Wd}{W_d} ]

Where (Ws) represents the weight of swollen hydrogels and (Wd) is the weight of freeze-dried hydrogels [15]. Highly crosslinked structures exhibit lower swelling ratios, while less crosslinked structures show higher swelling ratios [15].

Stimuli-responsive "smart" hydrogels undergo significant changes in swelling behavior in response to environmental variations such as pH, temperature, electric field, light, and specific biomolecules [15]. For instance, temperature-sensitive hydrogels like poly(N-isopropyl acrylamide) (PNIPAM) exhibit swelling changes at critical solution temperatures, while pH-sensitive hydrogels based on polyacrylic acid (PAA) or polymethacrylic acid (PMAA) swell differently depending on the protonation state of their ionic groups [15].

Table 2: Key Performance Parameters of Hydrogels for Bioelectronics

| Parameter | Measurement Techniques | Typical Range | Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Swelling Ratio | Gravimetric analysis | 10-1000% of dry weight | Cross-linking density, polymer hydrophilicity, environmental conditions [15] |

| Elastic Modulus | Rheometry, tensile testing | 0.1-100 kPa (matching biological tissues) [14] | Polymer concentration, cross-linking density, network structure [15] |

| Degradation Rate | Mass loss monitoring, structural analysis | Days to months | Chemical composition, enzymatic activity, environmental factors [15] |

| Pore Size | Scanning electron microscopy | Nanoscale to micrometers (2-10 μm in PVA systems) [14] | Synthesis conditions, polymer concentration, freezing methods (for cryogels) |

Synthesis and Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Preparation of Anisotropic PVA/PANI Hydrogels via Low-Temperature Polymerization [16]

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a homogeneous mixture of PVA, aniline, and initiator in aqueous solution.

- Directional Freezing: Freeze the solution in a unidirectional vertical gradient to facilitate directional growth of ice crystals, forming a 3D honeycomb structure.

- Restricted Polymerization: Under these low-temperature conditions, aniline undergoes restricted polymerization at the interface between ice crystals and PVA walls.

- Scaffold Formation: Allow PANI nanofibers to slowly form a scaffold, ultimately yielding an anisotropic PVA/PANI hydrogel (APPH) with an interpenetrating network structure.

- Post-processing: Thaw the hydrogel and rinse to remove unreacted monomers, then characterize using SEM, rheometry, and electrical conductivity measurements.

This method produces hydrogels with bicontinuous phase structure consisting of ion-conducting PVA and electrochemically active PANI scaffolds with high mechanical strength and superelasticity [16].

Liquid Metals

Fundamental Properties and Composition

Liquid metals (LMs) are metals or alloys that exist in liquid state at or near room temperature. Gallium-based alloys have garnered significant attention due to their safety profile and combination of advantageous thermophysical properties compared to mercury [18]. The most common LMs for flexible bioelectronics include:

- EGaIn: Eutectic gallium-indium (75% Ga, 25% In by weight) with melting point of 15.7°C [17]

- Galinstan: Eutectic gallium-indium-tin (68.5% Ga, 21.5% In, 10% Sn by weight) [17]

These materials exhibit exceptional properties including high electrical conductivity (3.4×10⁶ S/m for EGaIn), high thermal conductivity, fluidity, stretchability, and self-healing capabilities [17]. A critical aspect of LM behavior is the formation of a thin, passivating oxide skin (primarily Ga₂O₃) upon exposure to air, which stabilizes shapes against surface tension and enables patterning [17].

Synthesis and Processing Techniques

Liquid metal composites can be prepared through physical and chemical approaches:

Physical Synthesis Methods [17]:

- Mechanical mixing of bulk LM or LM nano/microdroplets with polymer precursors, inorganic flakes, and metallic particles

- Using LMs as fillers in soft/porous matrices

- Sonication to create LM emulsion with controlled droplet size

Protocol: Preparation of LM-Based Microwires through Thermal Drawing [18]

- Co-extrusion: Co-extrude EGaIn as core element and styrene-ethylene/butylene-styrene (SEBS) as shell material

- Thermal Drawing: Apply thermal drawing to the extrudates to reduce dimensions

- Dimension Control: Vary feed speed of co-extruded materials and drawing speed to control core diameter and shell thickness

- Characterization: Assess electrical properties under stretching and kinking deformation

This process enables production of LM-based microwires with core diameters as small as 52±14 μm and shell thickness of 46±10 μm, which maintain conductivity under deformation and exhibit self-healing properties [18].

Applications in Bioelectronics

Liquid metals find applications across multiple bioelectronic domains:

- Flexible electrodes for electrophysiological signal monitoring

- Stretchable conductors for wearable sensors and electronic skins

- Thermal interface materials for heat management in implantable devices

- Drug carriers in therapeutic delivery systems [17]

The compatibility of Galinstan with diamond coatings has been demonstrated, with no penetration or corrosion observed, though long-term oxidation and hydrolysis to GaOOH remains a challenge [18].

Conductive Polymers

Fundamental Properties and Doping Mechanisms

Conductive polymers (CPs) represent a class of organic materials that combine the electrical properties of metals and semiconductors with the mechanical flexibility and processing advantages of conventional polymers [19]. The fundamental structure consists of a conjugated carbon backbone with alternating single (σ) and double (π) bonds, where highly delocalized, polarized, and electron-dense π-bonds enable charge transport [19].

A critical factor in enhancing conductivity is doping, which introduces additional charge carriers (electrons for n-type or holes for p-type) into the polymer matrix. This process generates quasi-particles that facilitate charge transport along and between polymer chains, dramatically increasing electrical conductivity while modifying electronic structure, morphology, stability, and optical properties [19].

Major Conductive Polymer Systems

Key conductive polymers for biomedical applications include:

- Polyaniline (PANI): Good environmental stability, tunable conductivity through doping

- Polypyrrole (PPy): Excellent biocompatibility, commonly used in biosensors and neural interfaces

- Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT): High conductivity, stability, often used with polystyrene sulfonate (PSS) as PEDOT:PSS

- Polythiophene (PT) and derivatives: Used in organic electronics and antimicrobial coatings [19]

Table 3: Performance Characteristics of Major Conductive Polymers

| Polymer | Conductivity Range (S/cm) | Key Advantages | Primary Biomedical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| PANI | 10⁻¹⁰–10⁵ | Tunable conductivity, environmental stability, cost-effectiveness | Biosensors, antimicrobial coatings [19] |

| PPy | 10⁻⁸–10⁴ | Excellent biocompatibility, ease of synthesis, redox activity | Biosensors, neural interfaces, artificial muscles [19] |

| PEDOT | 10⁻⁶–10³ | High conductivity, transparency, stability (as PEDOT:PSS) | Bioelectrodes, neural interfaces, transparent conductors [19] |

| PT | 10⁻⁸–10⁴ | Structural versatility, optoelectronic properties | Biosensors, antimicrobial coatings [19] |

Synthesis and Processing for Bioelectronics

Protocol: Preparation of Conductive Polymer-Based Biosensors

- Monomer Preparation: Purify monomers (pyrrole, aniline, or EDOT) through distillation or recrystallization

- Oxidative Polymerization: Initiate polymerization using chemical oxidants (e.g., FeCl₃, ammonium persulfate) or electrochemical methods

- Doping: Introduce dopant ions during or after polymerization to enhance conductivity

- Composite Formation: Incorporate biocompatible additives or nanostructures to improve mechanical properties and biocompatibility

- Device Fabrication: Process into final form (films, coatings, patterned structures) using techniques such as spin-coating, inkjet printing, or electrodeposition

The biomedical application landscape for conductive polymers shows biosensors leading in both research and patent activity, followed by bioelectrical stimulation and neural interfaces [19]. Artificial muscles and implantable prosthetics exhibit high patent-to-journal ratios, indicating strong commercialization potential [19].

Composite Materials and Advanced Applications

Conductive Composite Hydrogels

Conductive composite hydrogels have emerged as promising materials that address the limitations of individual material systems. By introducing conductive fillers into hydrogel matrices, these composites form functional systems integrating tunable conductivity, mechanical robustness, and biocompatibility [16]. These materials can be classified based on their conductive filler type:

- Conductive polymer-based: PPy, PANI, or PEDOT incorporated into hydrogel networks

- LM-based: EGaIn or Galinstan droplets dispersed in hydrogel matrices

- Carbon-based: Graphene, carbon nanotubes, or carbon black added to hydrogels

- Metallic nanoparticle-based: Silver, gold, or other metal nanoparticles within hydrogels

Protocol: Preparation of PPy-Based Conductive Composite Hydrogels

- Hydrogel Matrix Formation: Prepare hydrogel network using natural (chitosan, gelatin) or synthetic (PVA, PAAm) polymers

- In-situ Polymerization: Incorporate pyrrole monomer into hydrogel network and initiate oxidative polymerization

- Doping: Introduce dopant anions (e.g., chloride, sulfate, polystyrene sulfonate) during polymerization

- Characterization: Evaluate electrical conductivity, mechanical properties, and biocompatibility

These composites address critical challenges in bioelectronic interfaces by providing tissue-matching mechanical properties while maintaining efficient electrical conduction for high-fidelity signal acquisition [16].

Applications in Bioelectronics and Biomedical Devices

Advanced applications of these material classes in bioelectronics include:

Electronic Skins (E-skins) based on conductive composite hydrogels can monitor physiological parameters, human motion, and environmental stimuli in real-time [16]. Their tissue-like softness and biocompatibility enable seamless integration with human skin for continuous health monitoring.

Neural Interfaces utilizing conductive polymers or LM composites provide soft, compliant electrodes that minimize foreign body response and maintain stable electrical performance for neural recording and stimulation [19] [13].

Drug Delivery Systems leverage the responsive properties of hydrogels and conductive polymers for controlled therapeutic release. For instance, electrically-triggered drug release from conductive polymer systems enables precise, localized administration of therapeutics [19].

Tissue Engineering Scaffolds incorporating conductive elements within hydrogel matrices support cell growth and regeneration while providing electrical stimulation for enhanced tissue development, particularly in electrically responsive tissues like nerve and muscle [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Soft Bioelectronics Material Development

| Reagent/Category | Function/Purpose | Examples/Specific Reagents |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogel Polymers | Form primary network structure providing mechanical framework and hydration | Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polyacrylamide (PAAm), polyethylene glycol (PEG), chitosan, gelatin [16] [15] |

| Conductive Polymers | Provide electronic conductivity and electrochemical activity | Polyaniline (PANI), polypyrrole (PPy), PEDOT:PSS [19] |

| Liquid Metals | Create highly deformable conductive pathways | EGaIn (75% Ga, 25% In), Galinstan (68.5% Ga, 21.5% In, 10% Sn) [17] |

| Cross-linking Agents | Establish network connectivity determining mechanical properties | Glutaraldehyde, genipin, ammonium persulfate (APS), N,N'-methylenebisacrylamide (MBAA) [15] |

| Dopants | Enhance electrical conductivity through charge carrier introduction | Hydrochloric acid, camphorsulfonic acid, polystyrene sulfonate, ferric chloride [19] |

| Oxidants | Initiate polymerization of conductive polymers | Ammonium persulfate, ferric chloride, hydrogen peroxide [19] |

| Stabilizers/Surfactants | Control LM droplet formation and prevent aggregation | Sodium dodecyl sulfate, Triton X-100, polyvinylpyrrolidone [17] |

| Biocompatibility Agents | Enhance biological integration and reduce immune response | Heparin, collagen, fibronectin, laminin [15] |

Hydrogels, liquid metals, and conductive polymers represent foundational material classes that enable the development of advanced soft bioelectronic systems. Each material offers unique advantages: hydrogels provide tissue-like mechanical properties and biocompatibility, liquid metals deliver unparalleled stretchability and self-healing capabilities, and conductive polymers bridge the gap between organic electronics and biological interfaces.

The future of these materials lies in the development of sophisticated composites that combine their respective advantages while mitigating individual limitations. Key research directions include improving long-term stability under physiological conditions, enhancing biocompatibility for chronic implants, developing scalable manufacturing processes, and creating multifunctional systems that combine sensing, actuation, and therapeutic capabilities. As these materials continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly unlock new possibilities in personalized medicine, advanced diagnostics, and bioelectronic therapeutics.

The integration of these material classes—through conductive composite hydrogels, LM-polymer hybrids, and other innovative combinations—represents the forefront of soft bioelectronics research, promising to transform how we interface electronic technology with biological systems for improved healthcare outcomes.

The field of soft bioelectronics is undergoing a fundamental transformation, shifting from a design philosophy centered on permanence and durability to one that embraces transience and resorption. This paradigm, critical for next-generation medical implants and sustainable electronics, leverages bioresorbable and self-healing materials to create devices that perform their function over a clinically relevant timeframe before safely dissolving in the body or environment [20]. These transient electronics address key limitations of conventional permanent implants, including long-term foreign body response, infection risks, and the need for secondary surgical removal [21] [22]. The core principle rests on the deliberate selection and integration of materials—both functional and structural—that are designed to disintegrate upon exposure to specific triggers, such as aqueous fluids or enzymatic activity, following predictable kinetics [20].

Framed within broader soft bioelectronics research, these technologies represent a convergence of materials science with biomedical engineering, aiming to achieve seamless, biocompatible integration with biological tissues. The mechanical properties of these materials—such as softness, stretchability, and conformability—are engineered to match those of dynamic biological systems, thereby minimizing mechanical mismatch at the tissue-device interface [9] [23]. This review provides an in-depth technical examination of the material systems, degradation mechanisms, fabrication strategies, and characterization methods underpinning this emerging field, serving as a guide for researchers and scientists developing the next wave of transient biomedical devices.

Material Systems for Transient Functionality

The development of high-performance transient electronics requires a diverse palette of materials that offer both excellent electronic functionality and controlled disintegration. These materials span the categories of conductors, semiconductors, and dielectrics.

Bioresorbable Conductors and Semiconductors

Conductive elements in transient devices are typically fabricated from metals or conductive polymers that degrade into non-toxic byproducts.

- Bioresorbable Metals: Magnesium (Mg) and Zinc (Zn) are the most widely used transient conductors, serving as interconnects and electrodes. Their degradation is governed by oxidation and hydrolysis, with rates varying significantly based on the physiological environment. Mg degrades at approximately 1.2–12 µm/day in simulated body fluid (SBF) at 37°C, while Zn degrades at about 3.5 µm/day in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 37°C [20]. For applications requiring longer stability, Molybdenum (Mo) and Tungsten (W) offer slower dissolution profiles of 0.001 µm/day and 0.48–1.44 µm/day, respectively [20].

- Conductive Polymers: Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) is a cornerstone material for soft, conductive layers. When combined with crosslinkers like 2,4-hexadiyne-1,6-diol (HDD) and processed with secondary dopants (e.g., methanol or H₂SO₄), it can achieve conductivities as high as ~2000 S/cm [24]. Its organic nature and tunable properties make it ideal for conformal biointerfaces.

The semiconductor layer is critical for active device operation. While single-crystalline silicon was the first major bioresorbable semiconductor discovered, the material palette is expanding.

- Silicon and Germanium: The degradation of single-crystalline silicon in aqueous environments is well-characterized, with rates highly sensitive to temperature, pH, and the presence of specific ions (e.g., HPO₄²⁻, Cl⁻) [20]. Germanium (Ge) nanomembranes and silicon-germanium (SiGe) alloys have also been successfully implemented in devices like strain and temperature sensors, offering proven biocompatibility and gas-free dissolution [20].

- Organic and Oxide Semiconductors: A composite of poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT) nanofibrils within a poly(l-lactide-co-ε-caprolactone) (PLCL) matrix has been demonstrated as a solution-processable, degradable semiconductor. The optimum PLCL:P3HT ratio of 8:2 balances electrical performance with mechanical stretchability [24]. Indium–gallium–zinc oxide (IGZO) and zinc oxide (ZnO) are other promising semiconductors for transient thin-film transistors and logic circuits [20].

Table 1: Characteristics of Key Bioresorbable Semiconductor and Conductor Materials

| Material | Function | Degradation Rate | Key Properties | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnesium (Mg) | Conductor | 1.2-12 µm/day (in SBF, 37°C) [20] | High conductivity, biocompatible degradation products | Electrodes, interconnects [20] |

| PEDOT:PSS | Conductor | Tunable via crosslinking & encapsulation | Up to ~2000 S/cm conductivity, soft, stretchable [24] | Conductive traces, neural interfaces [24] |

| Silicon (Si) | Semiconductor | Tunable via crystallinity & doping [20] | High-performance, well-understood dissolution | Diodes, transistors, CMOS circuits [20] |

| P3HT/PLCL Composite | Semiconductor | 0.12 μm/day (slower than PLCL) [24] | Solution-processable, elastic, degradable | Soft, stretchable thin-film transistors (TFTs) [24] |

Substrates, Encapsulants, and Self-Healing Materials

The substrate forms the structural backbone of the device, while encapsulation layers are paramount for controlling the functional lifetime.

- Biodegradable Polymers: Materials like PLCL and other biodegradable polyesters undergo hydrolysis, cleaving their ester bonds over time. The degradation rate is influenced by molecular weight (Mn), temperature, and pH. For example, higher Mn PLCL degrades faster due to a higher density of hydrolyzable bonds [24]. Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) and polycaprolactone (PCL) are also widely used for this purpose [20] [25].

- Encapsulation Strategies: Precise lifetime control is achieved through encapsulation layers that act as protective barriers. Recent work demonstrates that incorporating silicon dioxide (SiO₂) or zinc oxide (ZnO) flakes into a biodegradable polymer matrix can delay the onset of degradation, enabling devices to retain mechanical integrity for over 40 days in vivo [26]. The aspect ratio (width-to-thickness) of these filler flakes is a critical design parameter that can be modeled to fine-tune the degradation profile passively [26].

While the search results provided a stronger focus on bioresorption, the field of self-healing materials is a critical complementary paradigm for enhancing the durability and reliability of transient electronics during their operational life. These materials, often based on liquid metal alloys (e.g., gallium-based) or dynamic covalent polymer networks, can autonomously repair mechanical damage, such as cracks or breaks in conductive traces, thereby recovering electrical functionality and extending the device's usable lifetime under dynamic strain [23].

Degradation Mechanisms and Kinetics

The dissolution of transient electronic materials follows specific chemical pathways, primarily hydrolysis and enzymatic cleavage, depending on the material's chemical nature.

- Hydrolysis: This is the dominant mechanism for many polymers (e.g., PLC, PLGA) and semiconductors like silicon. For polymers, it involves the cleavage of backbone ester bonds by water molecules. For silicon, the reaction is: Si + 2H₂O → SiO₂ + 2H₂, followed by the hydration of SiO₂ to form soluble silicic acid [Si(OH)₄] [20].

- Enzymatic Degradation: Certain biopolymers, such as silk fibroin, are susceptible to enzymatic breakdown by proteases found in biological environments [20].

- Oxidation and Corrosion: Bioresorbable metals like Mg degrade via electrochemical corrosion: Mg + 2H₂O → Mg(OH)₂ + H₂. The formation of a passivating layer of Mg(OH)₂ can slow the process, but ions like Cl⁻ in physiological fluids can disrupt this layer, accelerating corrosion [20].

The kinetics of these processes are influenced by multiple external factors, allowing for programmable device lifetimes. Key influencing factors include:

- pH: Higher pH (alkaline conditions) generally accelerates the hydrolysis of polyester substrates [24].

- Temperature: Elevated temperatures significantly increase degradation rates across all material classes [20].

- Ionic Environment: The presence of specific ions, such as chloride (Cl⁻) and hydrogen phosphate (HPO₄²⁻), can catalyze the dissolution of silicon and the corrosion of magnesium [20].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between material composition, environmental triggers, and the resulting degradation pathway.

Degradation Pathway Logic

Table 2: Degradation Triggers and Rates for Selected Materials

| Material | Primary Degradation Mechanism | Key Influencing Factors | Reported Degradation Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLCL Substrate | Hydrolysis of ester bonds | pH, Temperature, Molecular Weight (Mn) [24] | ~0.21 µm/day (PBS, pH 7, 37°C) [24] |

| P3HT/PLCL Semiconductor | Hydrolysis (slowed by P3HT hydrophobicity) | Temperature, pH [24] | ~0.12 µm/day (PBS, pH 7, 37°C) [24] |

| Magnesium (Mg) | Corrosion/Oxidation | Ion concentration (e.g., Cl⁻), pH [20] | 1.2-12 µm/day (SBF, pH 7.4, 37°C) [20] |

| Silicon (Si) | Hydrolysis & Oxidation | Ion concentration (HPO₄²⁻, Cl⁻), Crystallinity, Doping [20] | Tunable from days to years [20] |

Fabrication and Manufacturing Strategies

A significant challenge for transient electronics is developing fabrication processes that are scalable, cost-effective, and compatible with sensitive biodegradable materials.

Monolithic 3D Fabrication via Photopatterning

Recent advances have demonstrated a solution-processable and photo-patternable approach for creating sophisticated, multi-layered devices. This strategy enables the fabrication of sensors, transistors, microheaters, and capacitors on a single, ultrathin (~3 μm) elastic substrate [24]. The workflow involves sequential, layer-by-layer deposition and patterning of optimized organic materials:

- Substrate/Insulator Formation: A biodegradable elastic polymer (e.g., UV-curable PLCL) is synthesized, spin-coated, and crosslinked via UV exposure to form the device substrate [24].

- Semiconductor Patterning: A semiconducting layer (e.g., P3HT nanofibrils in a PLCL matrix) is deposited. A diazirine crosslinker is used to form a stretchable network upon UV irradiation, enabling photopatterning of the semiconductor [24].

- Conductor Patterning: A conductive ink (e.g., PEDOT:PSS with HDD crosslinker) is cast and patterned using UV lithography. Exposure to 254 nm light induces topochemical polymerization, creating water-resistant, highly conductive traces [24].

This method offers significant advantages in resolution (down to a few microns), speed, and cost reduction compared to traditional microfabrication, making it highly suitable for producing large-area biointegrated electronic systems [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Fabricating Soft Transient Electronics

| Reagent / Material | Function | Brief Explanation of Role |

|---|---|---|

| UV-PLCL (Acrylated) | Substrate/Insulator | A UV-curable, biodegradable elastomer that forms the soft, degradable backbone of the device [24]. |

| P3HT (Poly(3-hexylthiophene)) | Semiconductor | Provides the semiconducting properties. Used as nanofibrils for superior carrier mobility [24]. |

| PEDOT:PSS | Conductor | A conductive polymer complex used to form flexible, patternable electrodes and interconnects [24]. |

| 2,4,6-Trimethylbenzoyldiphenylphosphine oxide (TPO) | Photoinitiator | Generates free radicals upon UV exposure to initiate crosslinking of the UV-PLCL monomer [24]. |

| 2,4-Hexadiyne-1,6-diol (HDD) | Crosslinker | Undergoes topochemical polymerization under 254 nm UV to pattern and insolubilize PEDOT:PSS traces [24]. |

| Diazirine Crosslinker | Crosslinker | Forms carbenes under UV to create crosslinks between P3HT and the polymer matrix, enabling a patterned, stretchable semiconductor [24]. |

| Silicon Dioxide (SiO₂) Flakes | Encapsulation Filler | Mixed into polymer matrices to control the device's dissolution rate by lengthening the pathway for water ingress [26]. |

The following diagram summarizes the key steps in this monolithic fabrication process.

Monolithic 3D Fabrication Workflow

Experimental Protocols and Characterization

Rigorous characterization is essential to correlate material properties with device performance and degradation behavior. Below is a detailed methodology for key experiments cited in this field.

Protocol: In Vitro Degradation Kinetics Study

Objective: To quantitatively characterize the dissolution profile and functional lifetime of a fabricated transient electronic device under accelerated or physiologically relevant conditions [24] [26].

Materials:

- Device Under Test (DUT): e.g., a fabricated PLCL-based electrode array.

- Incubation Medium: Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), simulated body fluid (SBF), or solutions at varying pH (e.g., pH 7.4 and pH 13 for accelerated testing).

- Environmental Chamber: Set to 37°C to mimic physiological temperature.

- Analytical Tools: Optical microscope, scanning electron microscope (SEM), impedance analyzer, scale for mass loss measurement.

Procedure:

- Baseline Characterization: Record initial mass, thickness, optical images, and electrical performance (e.g., impedance, conductivity) of the DUT.

- Immersion: Immerse the DUT in the selected incubation medium, ensuring the device is fully submerged. Maintain the environment at a constant temperature (e.g., 37°C).

- Periodic Sampling: At predetermined time intervals (e.g., daily, weekly), remove samples from the medium (n≥3 for statistical significance).

- Rinsing and Drying: Gently rinse samples with deionized water and dry under a stream of nitrogen or in a desiccator for mass loss and imaging analysis. Note: For electrical testing, measurements may be performed in-situ or on carefully blotted (not fully dried) samples to preserve the degradation state.

- Analysis:

- Mass Loss: Measure and record the mass of the dried samples to calculate the percentage of mass loss over time.

- Morphology: Use optical microscopy and SEM to document physical changes, such as cracking, delamination, and fragmentation.

- Functional Performance: Measure the electrical impedance of electrodes or the operational characteristics of transistors.

- Chemical Analysis: Use techniques like Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) or Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) to track chemical bond cleavage and molecular weight changes in polymers.

- Data Modeling: Fit the mass loss and electrical performance data to kinetic models (e.g., first-order decay) to extract degradation rate constants and predict functional lifetime.

Protocol: Electrochemical Performance of Soft Electrodes

Objective: To evaluate the electrical stability and interface impedance of soft, conductive electrodes (e.g., PEDOT:PSS) under mechanical strain and in biological fluids, a key metric for bio-sensing applications [24] [23].

Materials:

- Fabricated electrode on a soft substrate.

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat with impedance capability.

- Electrochemical cell (3-electrode setup: working electrode = DUT, counter electrode = Pt wire, reference electrode = Ag/AgCl).

- Custom-built or commercial tensile strain stage.

Procedure:

- Setup: Mount the soft electrode in the electrochemical cell containing PBS at 37°C.

- Cyclic Voltammetry (CV): Perform CV scans (e.g., from -0.2 V to 0.6 V vs. Ag/AgCl at 50 mV/s) to assess the electrochemical activity and stability.

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): Measure impedance spectra (e.g., from 1 Hz to 100 kHz at open circuit potential with a 10 mV AC amplitude).

- Strain Testing: Repeat steps 2 and 3 while applying uniaxial tensile strain to the substrate (e.g., 0%, 10%, 30% strain) to evaluate performance under deformation.

- Data Analysis: Extract the charge storage capacity (CSC) from the CV curves. Analyze EIS data by fitting to an equivalent circuit model (e.g., a Randles circuit) to determine the interface impedance, a critical parameter for signal-to-noise ratio in sensing.

Applications in Biomedical Devices and Beyond

Bioresorbable and self-healing materials are enabling a new class of medical devices that seamlessly integrate with the body for therapeutic and diagnostic functions before safely disappearing.

- Neuromodulation and Recovery: Fully bioresorbable electrical stimulators have been developed to promote nerve regeneration after injury. These devices provide critical therapeutic stimulation during the initial healing phase and then degrade, eliminating the need for surgical removal [20]. Similarly, soft, conformable electrode arrays can be implanted on the brain cortex for electrocorticography (ECoG) monitoring and then dissolve [20] [24].

- Cardiac Rhythm Management: Temporary, battery-free, and bioresorbable pacemakers have been designed for on-demand cardiac rhythm management during the postoperative recovery period, after which the device dissolves [20] [24].

- Wound Healing and Drug Delivery: Dissolvable sensors can monitor healing parameters (pH, temperature) at wound sites and release growth factors or drugs in a spatiotemporally controlled manner, with the entire system degrading as the tissue regenerates [22] [23].

- Environmental Sensing: Beyond medicine, transient electronics are deployed as eco-friendly sensors for monitoring soil, water, or aquatic conditions. These devices perform their function and then decompose in the environment, preventing persistent electronic waste [20] [25].

The paradigm of bioresorbable and self-healing materials is fundamentally reshaping the design and application of soft bioelectronics. By engineering material systems that harmonize with biological timescales and environments, researchers are creating transient devices that eliminate the long-term risks and limitations associated with permanent implants. The progress in understanding degradation mechanisms, developing sophisticated material palettes, and establishing scalable fabrication methods like monolithic 3D photopatterning has positioned this field for significant growth.

Future research will need to tackle several key challenges to realize the full potential of this technology. These include expanding the library of high-performance biodegradable semiconductors with diverse bandgaps, developing fully biodegradable and high-energy-density power sources, and establishing standardized regulatory pathways for these dynamic devices. Furthermore, the integration of intelligent, feedback-controlled systems that can actively respond to physiological cues will pave the way for truly autonomous, closed-loop therapeutic platforms. The convergence of bioresorbable materials with self-healing capabilities and soft electronics promises a future where medical implants are not only minimally invasive and effective but also temporary and smart, ultimately dissolving away after their work is done.

From Lab to Life: Fabrication Techniques and Breakthrough Applications in Healthcare

The development of soft and flexible bioelectronics represents a paradigm shift in medical devices, demanding fabrication technologies that can bridge the mechanical mismatch between traditional rigid electronics and biological tissues. This technical guide examines three core advanced fabrication techniques—3D printing, electrospinning, and transfer printing—within the context of soft bioelectronics materials research. These methods enable the creation of devices with tissue-like mechanical properties, enhanced biocompatibility, and sophisticated functionality for applications ranging from implantable sensors to tissue engineering scaffolds and drug delivery systems. The convergence of these fabrication approaches allows researchers to overcome individual technological limitations, creating synergistic platforms that support next-generation biomedical innovations [27] [6].

Core Fabrication Technologies

Electrospinning Fundamentals

Electrospinning is a versatile technique for producing micro- and nanoscale fibers that closely mimic the native extracellular matrix (ECM). The process involves applying a strong electric field to a polymer solution or melt, which overcomes the liquid's surface tension and draws it into fine fibers that are deposited on a collector [27] [28].

Process Parameters and Setup: A basic electrospinning system consists of four main components: a high-voltage power supply (typically 10-25 kV), a solution storage unit (e.g., syringe), an ejection device (spinneret or needle), and a collection device. The applied voltage creates an electromagnetic field between the spinneret and collector, deforming the polymer solution droplet into a Taylor cone from which a charged polymer jet is ejected. This jet undergoes rapid stretching and whipping motions during its trajectory to the collector, resulting in solvent evaporation and the formation of solid fibers with diameters ranging from tens of nanometers to several micrometers [27] [28].

Critical Parameters Influencing Fiber Morphology:

- Solution Parameters: Polymer molecular weight and concentration directly affect solution viscosity. Lower molecular weights or concentrations often result in bead formation instead of uniform fibers, while higher values promote uniform fiber formation but may lead to clogging if viscosity becomes excessive. Solvent properties, particularly dielectric constant, significantly impact fiber diameter and morphology [27].

- Process Parameters: Applied voltage, flow rate, and tip-to-collector distance critically influence final fiber characteristics. Optimal voltage must be carefully determined as both insufficient and excessive voltage can cause bead formation or non-uniform fibers. Increased collector distance generally reduces fiber diameter and improves uniformity by allowing more time for solvent evaporation and jet stretching [27].

- Environmental Factors: Temperature and humidity affect solvent evaporation rates and consequently impact fiber morphology and surface characteristics [28].

Electrospinning Variants: The technology is primarily categorized into solution electrospinning (using polymer solutions) and melt electrospinning (using polymer melts). Solution electrospinning can achieve nanoscale fibers but often involves toxic organic solvents. Melt electrospinning offers a solvent-free alternative but typically produces larger diameter fibers and presents challenges related to thermal degradation and equipment complexity [28].

3D Printing Technologies

Additive manufacturing, particularly 3D printing, has revolutionized the fabrication of soft bioelectronic devices by enabling precise control over architecture and customization. Several 3D printing techniques are particularly relevant for soft devices:

Digital Light Processing (DLP): This vat polymerization technique projects 2D light patterns onto a vat of photopolymer resin, curing complete layers simultaneously. DLP offers high resolution (down to 1 μm), fast printing speeds, smooth surface finishes, and compatibility with various photocurable materials including hydrogels, elastomers, and ionogels. Recent advancements like grayscale DLP (g-DLP) enable spatial control of material properties by varying light intensity, while multi-material DLP systems facilitate heterogeneous constructs [29].

Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM): This extrusion-based method melts and deposits thermoplastic filaments layer-by-layer. FDM offers cost-effectiveness, precision, and scalability, making it suitable for creating customized scaffold structures with specific shapes and porosity. However, it typically provides lower resolution than DLP and is limited to thermoplastic materials [30].

Emerging 3D Printing Capabilities: Continuous Liquid Interface Production (CLIP) dramatically accelerates printing speed by utilizing oxygen inhibition to prevent adhesion to the vat bottom. Multi-material printing systems enable complex, heterogeneous devices with integrated functionality. Portable, low-cost DLP systems based on smartphone projectors are increasing technology accessibility [29].

Transfer Printing and Alternative Approaches

While 3D printing and electrospinning are additive processes, transfer printing techniques enable the integration of functional components onto soft, stretchable substrates. This approach is particularly valuable for creating sophisticated bioelectronic interfaces that combine the performance of semiconductor materials with the mechanical compliance of biological tissues.

Recent breakthroughs in material science have enabled alternative pathways to soft bioelectronics. The development of hydrogel-based semiconductors represents a significant innovation, creating materials that are both semiconductive and possess tissue-like mechanical properties. These materials are synthesized using a solvent exchange process where semiconductors are first dissolved in a water-miscible organic solvent before being incorporated with hydrogel precursors, resulting in a single material that combines semiconducting functionality with hydrogel properties including high hydration, porosity, and softness [6].

Another pioneering approach utilizes the giant magnetoelastic effect in soft polymer systems. This discovery enables the creation of intrinsically waterproof bioelectronic devices that operate via magnetic fields rather than direct electrical connections, overcoming the limitation of traditional electronics in high-humidity biological environments [31].

Synergistic Integration of Fabrication Techniques

Hybrid 3D Printing and Electrospinning Approaches

The integration of 3D printing and electrospinning creates complementary fabrication platforms that overcome the individual limitations of each technology. Electrospinning produces nanofibrous structures that mimic the native extracellular matrix but often lacks mechanical stability and precise geometric control. Conversely, 3D printing enables the development of tailored structures with highly controlled architecture and improved mechanical strength but struggles to achieve nanoscale resolution [27].

Combined approaches produce scaffolds and devices that integrate nanoscale features for enhanced cellular interaction with macroscale designs that provide structural integrity. These hybrid strategies have shown particular promise in tissue-specific applications including bone regeneration, skin wound healing, and nerve repair [27]. For instance, bilayered scaffolds for osteochondral repair utilize a 3D-printed base layer that provides porous mechanical support, combined with an electrospun membrane top layer that acts as a barrier against unwanted tissue infiltration [30].

The table below summarizes the complementary characteristics of these technologies and the benefits of their integration:

Table 1: Complementary Characteristics of 3D Printing and Electrospinning

| Parameter | 3D Printing | Electrospinning | Integrated Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Macroscale to microscale (typically ≥50 μm) [27] | Nanoscale to microscale (50 nm - 10 μm) [28] | Multiscale architecture from nano to macro |

| Mechanical Properties | High structural strength, customizable stiffness [27] | Limited mechanical stability, high flexibility [27] | Optimized mechanical integrity with compliant interfaces |

| Architectural Control | High precision in 3D geometry, controlled porosity [29] | Random or aligned fibers, limited 3D control [27] | Precise 3D structures with biomimetic nanofeatures |

| Biomimicry | Limited at cellular level [27] | Excellent ECM mimicry, high surface area [28] | Enhanced biointegration at multiple hierarchical levels |

| Application Scope | Structural implants, custom devices [30] | Drug delivery, wound healing, filtration [28] | Advanced tissue engineering, bioactive implants |

Experimental Protocols for Hybrid Fabrication

Protocol 1: Fabrication of Bilayered Osteochondral Scaffolds

This protocol details the combined FDM 3D printing and electrospinning approach for creating functional bilayered scaffolds, as demonstrated in recent research [30]:

Materials:

- Polycaprolactone (PCL) pellets (80 kDa) and filament sticks

- Graphene nanoplatelets (GNP, 0.5 wt%)

- Osteogenon (OST) drug

- Solvents: chloroform, dimethylformamide (DMF)

3D Printing Parameters:

- Printer: Anet A8 FDM printer

- Nozzle Temperature: 190°C

- Bed Temperature: 50°C

- Layer Thickness: 0.2 mm

- Infill Pattern: Three layers of parallel bars (1 mm side length) with 0.7 mm spacing, oriented perpendicularly in adjacent layers

Electrospinning Parameters:

- Polymer Solution: PCL dissolved in chloroform/DMF (2:1 v/v) with OST incorporation

- Voltage: 15-20 kV

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/h

- Tip-to-Collector Distance: 15 cm

- Collector Type: Rotating mandrel for aligned fibers or static plate for random fibers

Fabrication Sequence:

- Produce GNP-modified PCL filament using injection molding with 0.5 wt% GNP incorporation

- 3D print the porous scaffold base layer using optimized FDM parameters

- Mount the 3D-printed structure on the electrospinning collector

- Electrospin the drug-loaded PCL/OST fibrous membrane directly onto the 3D-printed substrate

- Vacuum dry the bilayered scaffold for 24 hours to remove residual solvents

Table 2: Key Material Functions in Bilayered Scaffold Design

| Material | Function | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) | Structural polymer for both 3D printing and electrospinning | Biodegradability, excellent processability, mechanical strength [30] |

| Graphene Nanoplatelets (GNP) | Antibacterial modifier and mechanical enhancer | Antimicrobial properties via membrane damage and oxidative stress; improves ductility and crystallization [30] |

| Osteogenon (OST) | Osteoinductive drug component | Promotes bone regeneration through ossein and hydroxyapatite components [30] |

| Chloroform/DMF | Solvent system for electrospinning | Efficiently dissolves PCL, moderate volatility for controlled fiber formation [30] |

Protocol 2: DLP Printing of Soft Pneumatic Actuators

This protocol outlines the fabrication of soft pneumatic actuators with sensing capabilities using multi-material DLP printing [29]:

Materials:

- Photocurable elastomer resin (e.g., polyurethane-based)

- Conductive hydrogel resin

- Photoinitiator (e.g., phenylbis(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)phosphine oxide)

- Photoabsorber (e.g., Sudan I)

DLP Printing Parameters:

- Printer Configuration: Bottom-up projection with oxygen-permeable window

- Layer Thickness: 25-50 μm

- Exposure Time: 1-5 seconds per layer (optimized for resin formulation)

- Light Intensity: 5-20 mW/cm² at 405 nm wavelength

- Multi-material Approach: Centrifugal force-assisted resin exchange for heterogeneous structures

Fabrication Sequence:

- Design actuator geometry with integrated pneumatic channels and sensing elements

- Prepare elastomer and conductive hydrogel resins with optimized viscosity (<500 cps)

- Print main actuator body using elastomer resin

- Implement resin exchange protocol for multi-material printing

- Print conductive hydrogel sensing elements at critical deformation points

- Post-cure printed structure under UV light (365 nm, 10 minutes)

- Characterize actuation performance and sensing capability

Advanced Material Systems for Soft Bioelectronics

Hydrogel-Based Semiconductors

A groundbreaking advancement in soft bioelectronics is the development of hydrogel-based semiconductors that simultaneously exhibit semiconducting functionality and tissue-like mechanical properties. These materials address the fundamental mismatch between traditional rigid semiconductors and biological tissues, enabling seamless bioelectronic interfaces [6].

The fabrication of these materials employs a novel solvent exchange process:

- Semiconducting polymers are first dissolved in a water-miscible organic solvent

- The solution is combined with hydrogel precursors and gelation agents

- Polymerization creates a unified material that maintains both semiconducting capability and hydrogel characteristics

These hydrogel semiconductors demonstrate enhanced biosensing capabilities due to their porous structure that facilitates efficient diffusion of biomolecules to interaction sites. They also exhibit reduced immune responses and inflammation when implanted, addressing critical challenges in long-term bioelectronic integration [6].

Soft Magnetoelastic Materials

The recent discovery of the giant magnetoelastic effect in soft polymer systems represents a paradigm shift in bioelectronic sensing and energy harvesting. This phenomenon, previously observed only in rigid metals and alloys, involves variations in magnetic flux density under mechanical stress [31].

- Material Composition: Soft magnetoelastic composites typically consist of magnetic nanoparticles (e.g., neodymium-iron-boron) incorporated into elastomeric matrices (e.g., silicone, polyurethane).

- Fabrication Process:

- Magnetic particles are uniformly dispersed in the uncured elastomer precursor

- The mixture is cast or printed into desired geometries

- Cross-linking is induced thermally or via UV exposure

- The material is magnetically polarized in a strong external field

- Performance Characteristics: These materials exhibit significant changes in magnetic flux density under minimal mechanical pressure (as low as 10 kPa), making them suitable for detecting physiological signals such as arterial pulse waves, respiratory movements, and cardiac cycles [31].

A key advantage of magnetoelastic bioelectronics is their intrinsic waterproofness, as magnetic fields penetrate water and biological fluids without significant signal loss. This eliminates the need for bulky encapsulation layers that typically compromise device flexibility and performance [31].

Characterization and Performance Metrics

Structural and Mechanical Characterization

Rigorous characterization of soft devices is essential to ensure performance under physiological conditions. Key metrics include:

- Structural Analysis: Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) reveals fiber morphology, pore structure, and layer integration in hybrid scaffolds. Micro-computed tomography (μCT) provides 3D visualization of internal architecture and mineral deposition in bioactive scaffolds [30].

- Mechanical Properties: Tensile testing determines elastic modulus, strain at break, and toughness. Soft bioelectronic materials typically exhibit moduli ranging from <1 kPa (matching brain tissue) to several MPa (for load-bearing applications). Hydrogel semiconductors demonstrate mechanical properties similar to native tissues, with high stretchability (often >100% strain) and toughness (up to 420 MJ/m³ for advanced formulations) [32] [6].

- Surface Characteristics: Contact angle measurements assess hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity, which influences protein adsorption and cell adhesion. FTIR spectroscopy confirms chemical composition and functional group presence [30].

Functional Performance Metrics

- Electrical Properties: Conductivity measurements evaluate performance under deformation. Advanced conductive hydrogels maintain approximately 1.2 S/cm conductivity even under 100% tensile strain, with minimal impedance increase (<9%) after 10,000 mechanical cycles [32].

- Biointeractive Performance: Implantable devices are evaluated based on signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and foreign body response. Next-generation flexible bioelectronics demonstrate SNR of 37 dB compared to 15 dB for conventional Pt electrodes, while reducing fibrous capsule thickness to approximately 28.6 μm versus 85.2 μm for traditional materials [32].

- Antibacterial Efficacy: For antimicrobial applications, materials are tested against relevant pathogens. Graphene-incorporated scaffolds show significant antibacterial effectiveness against C. albicans and S. aureus through multiple mechanisms including physical membrane disruption and oxidative stress induction [30].

Table 3: Performance Metrics of Advanced Soft Bioelectronic Materials

| Material System | Key Performance Indicators | Values | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogel Semiconductors | Electrical conductivity, Modulus, Hydration | Tissue-like modulus (<1 kPa), High porosity, Enhanced biosensing [6] | Implantable sensors, Drug delivery devices |

| Soft Magnetoelastic Composites | Pressure sensitivity, Magnetic response, Waterproofness | Detection threshold: ~10 kPa, Intrinsically waterproof [31] | Wearable sensors, Implantable monitors |

| Conductive Hydrogels | Conductivity under strain, Toughness, Cyclic stability | 1.2 S/cm at 100% strain, 420 MJ/m³ toughness, <9% impedance increase after 10,000 cycles [32] | Flexible electrodes, Strain sensors |

| PCL/Graphene Scaffolds | Antibacterial efficacy, Strain at break, Mineralization | Enhanced against S. aureus & C. albicans, Increased ductility, Rapid apatite formation [30] | Bone tissue engineering, Osteochondral repair |

Applications in Soft Bioelectronics

Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine

The integration of 3D printing and electrospinning enables the creation of sophisticated scaffolds for tissue engineering that mimic the hierarchical organization of native tissues. Bilayered constructs provide distinct microenvironments for different cell types—for example, supporting both chondrogenic and osteogenic differentiation in osteochondral repair. The incorporation of bioactive molecules such as Osteogenon enhances bone regeneration, while graphene components provide antibacterial protection against postoperative infections [30].

Implantable and Wearable Bioelectronics

Advanced fabrication techniques have enabled a new generation of bioelectronic devices that seamlessly integrate with biological tissues:

- Neural Interfaces: Flexible bioelectronic systems with brain tissue-like modulus (<1 kPa) significantly reduce foreign body response and enable stable electrophysiological signal acquisition over extended periods (≥30 days). These systems can incorporate anti-inflammatory coatings that modulate macrophage polarization and suppress immune responses through reactive oxygen species scavenging [32].