Rigid vs. Soft Bioelectronics: A Comprehensive Performance Comparison for Next-Generation Medical Devices

This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of rigid and soft bioelectronics, targeting researchers and professionals in biomedical science and drug development.

Rigid vs. Soft Bioelectronics: A Comprehensive Performance Comparison for Next-Generation Medical Devices

Abstract

This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of rigid and soft bioelectronics, targeting researchers and professionals in biomedical science and drug development. It explores the foundational principles, material properties, and historical context of both paradigms. The review delves into current methodological innovations—including organic semiconductors and softening materials—and their applications in neurology, cardiology, and continuous monitoring. It systematically addresses critical challenges such as long-term stability, foreign body response, and power management, offering optimization strategies. Through a rigorous validation of mechanical, electrical, and biological performance metrics, this work synthesizes key trade-offs to guide the selection and development of bioelectronic technologies for enhanced clinical translation and therapeutic efficacy.

The Material Divide: Exploring the Fundamental Principles of Rigid and Soft Bioelectronics

A fundamental paradigm in bioelectronics centers on the mechanical compatibility between electronic devices and biological tissues. Conventional rigid bioelectronics, constructed from materials like silicon and metals, operate with a Young's modulus in the gigapascal (GPa) range. In stark contrast, soft biological tissues, including the skin, brain, and heart, exhibit moduli in the kilopascal (kPa) range [1] [2]. This several-orders-of-magnitude difference in stiffness creates a significant mechanical mismatch at the biointerface. This mismatch leads to critical failures such as poor conformal contact, device delamination, chronic inflammation, fibrotic encapsulation, and long-term signal degradation [1] [3] [2]. In response, the field of soft bioelectronics has emerged, leveraging polymers, elastomers, hydrogels, and novel composites to create devices with tissue-like mechanical properties, thereby enabling seamless and stable integration with the body for superior long-term performance [1] [4].

Core Material Properties: A Comparative Analysis

The divergence between rigid and soft bioelectronics is rooted in their constituent materials, which dictate their mechanical behavior, electrical performance, and overall biocompatibility.

Material Composition and Intrinsic Properties

- Rigid Bioelectronics: Rely on traditional electronic materials such as silicon, noble metals (e.g., gold, platinum), and ceramics. These materials are prized for their high electrical conductivity and well-established, high-yield microfabrication processes [1].

- Soft Bioelectronics: Employ a diverse toolkit of soft substances.

- Elastomers (e.g., polydimethylsiloxane - PDMS) provide stretchability and durability, with moduli tunable around the MPa range, making them suitable for skin and cardiac interfaces [4].

- Hydrogels feature high water content and moduli in the kPa range, closely matching the softness of brain tissue and enabling highly biocompatible interfaces [5] [4].

- Conductive Nanocomposites are created by dispersing conductive nanofillers (e.g., metal nanowires, carbon nanotubes, graphene) within soft polymeric matrices. This strategy decouples electrical conductivity from mechanical stiffness, allowing for the development of intrinsically stretchable and conductive materials [6] [4].

- Liquid Metals (e.g., Gallium-based alloys) offer unique combinations of metal-like conductivity and fluidic mechanical properties, enabling extreme stretchability and self-healing capabilities [7] [4].

Quantitative Comparison of Key Characteristics

The table below summarizes the fundamental differences between the two paradigms across critical performance metrics.

Table 1: Core Property Comparison of Rigid vs. Soft Bioelectronics

| Property | Rigid Bioelectronics | Soft & Flexible Bioelectronics |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Material Types | Silicon, metals, ceramics [1] | Polymers, elastomers, hydrogels, liquid metals, conductive composites [1] [4] |

| Young's Modulus | > 1 GPa [1] | 1 kPa – 1 MPa (typically) [1] |

| Bending Stiffness | > 10⁻⁶ Nm [1] | < 10⁻⁹ Nm [1] |

| Device Thickness | > 100 µm [1] | < 100 µm (often < 10 µm) [1] [7] |

| Stretchability | < 1% (brittle) [1] | > 10% (> 100% for ultra-soft devices) [1] |

| Tissue Integration | Stiffness mismatch causes inflammation and fibrotic encapsulation [1] | Soft, conformal materials match tissue mechanics and reduce immune response [1] |

| Chronic Signal Fidelity | Long-term degradation due to micromotion and scar tissue [1] [2] | Better chronic stability due to stable tissue contact and reduced scarring [1] [2] |

| Power/Data Interfaces | Mature, robust wired and wireless options [1] | Emerging soft antennas and skin-contact power; interfaces can be less robust [1] |

Experimental Performance Data and Benchmarking

Objective performance validation is crucial for comparing these technologies. Standardized experimental protocols are used to quantify electrical and mechanical performance.

Key Experimental Protocols

- Electrode-Skin Interface Impedance Measurement:

- Objective: To evaluate the quality of the electrical interface and signal transduction efficiency.

- Protocol: Impedance is typically measured using an electrochemical workstation in a two- or three-electrode configuration. Measurements are performed over a frequency range (e.g., 1 Hz to 10 kHz) under both resting and dynamic motion conditions. The results are normalized against the clinical gold standard, wet Ag/AgCl electrodes, to calculate a relative impedance ratio [7].

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) Assessment:

- Objective: To quantify the fidelity of recorded biosignals (e.g., ECG, EMG, EEG).

- Protocol: Electrodes are applied to human subjects to record specific biopotentials. The SNR is calculated as the ratio of the power of the desired signal to the power of the background noise. The SNR of the test electrode is normalized to that of a standard Ag/AgCl electrode tested under identical conditions on the same subject [7].

- Cyclic Mechanical Testing:

- Objective: To assess mechanical durability and electrical stability under repeated deformation.

- Protocol: Devices are subjected to repeated stretching or bending cycles (e.g., 1000+ cycles) using a mechanical tester. Changes in electrical resistance or performance of an integrated sensor are monitored throughout the test to determine failure points and long-term reliability [8] [6].

Comparative Performance Data

Recent advances in soft materials have enabled performance that meets or exceeds rigid standards. The following table compiles experimental data from recent studies on soft bioelectronic interfaces.

Table 2: Experimental Performance of Soft Bioelectronic Technologies

| Material/Technology | Key Performance Metric | Reported Value | Context & Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soft Skin-Interfacing Electrodes [7] | Relative Impedance & SNR | Impedance: <1x Ag/AgCl; SNR: up to 38 dB | Outperforms or matches clinical gel electrodes during motion, even with sweat. |

| Au/Nanofiber Electrode [8] | Electrical Stability under Bending | Resistance change < 4% after 2000 cycles | Demonstrates robust conductivity on a flexible, breathable substrate. |

| Tetrahedral DNA (TDNA) Biosensor [8] | Mechanical & Operational Stability | Signal variation < 3% after 1000 bends; < 8% attenuation over 4 weeks | Superior to ssDNA sensors; maintains detection fidelity in complex bioenvironments. |

| Soft Magnetoelastic Bioelectronics [9] | Operational Stability in Humid Environments | Stable performance without encapsulation | Magnetic fields penetrate water without loss, enabling intrinsically waterproof operation for implants and wearables. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Developing and testing these paradigms requires a specific set of materials and reagents. The following table details key components for a research toolkit focused on soft bioelectronics.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Soft Bioelectronics

| Category / Item | Function / Description | Key Characteristics & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Conductive Nanofillers | Provide electrical conductivity to insulating soft matrices. | Metal Nanowires (Au, Ag): High conductivity, form percolation networks [4].Carbon Nanotubes/Graphene: High aspect ratio, good mechanical properties [6] [4].Liquid Metals (e.g., EGaIn): Extreme stretchability, self-healing [7] [4]. |

| Stretchable Matrices | Provide the soft, flexible, or stretchable backbone of the device. | Elastomers (e.g., PDMS, TPU): MPa-range modulus, high elasticity, durability [4].Hydrogels (e.g., PAAm, Gelatin): kPa-range modulus, high water content, tissue-like [5] [4]. |

| Functional Polymers | Enable advanced electronic functions within soft formats. | Conductive Polymers (e.g., PEDOT:PSS, PANI): Mixed ionic-electronic conduction, excellent for OECTs [3] [4]. |

| Specialized Biosensing Elements | Enable specific detection of biochemical targets. | Tetrahedral DNA (TDNA): Provides a rigid, stable scaffold for aptamer-based sensors, reducing biofouling and enhancing stability [8].Aptamers: Target-specific recognition elements for proteins and biomarkers [8]. |

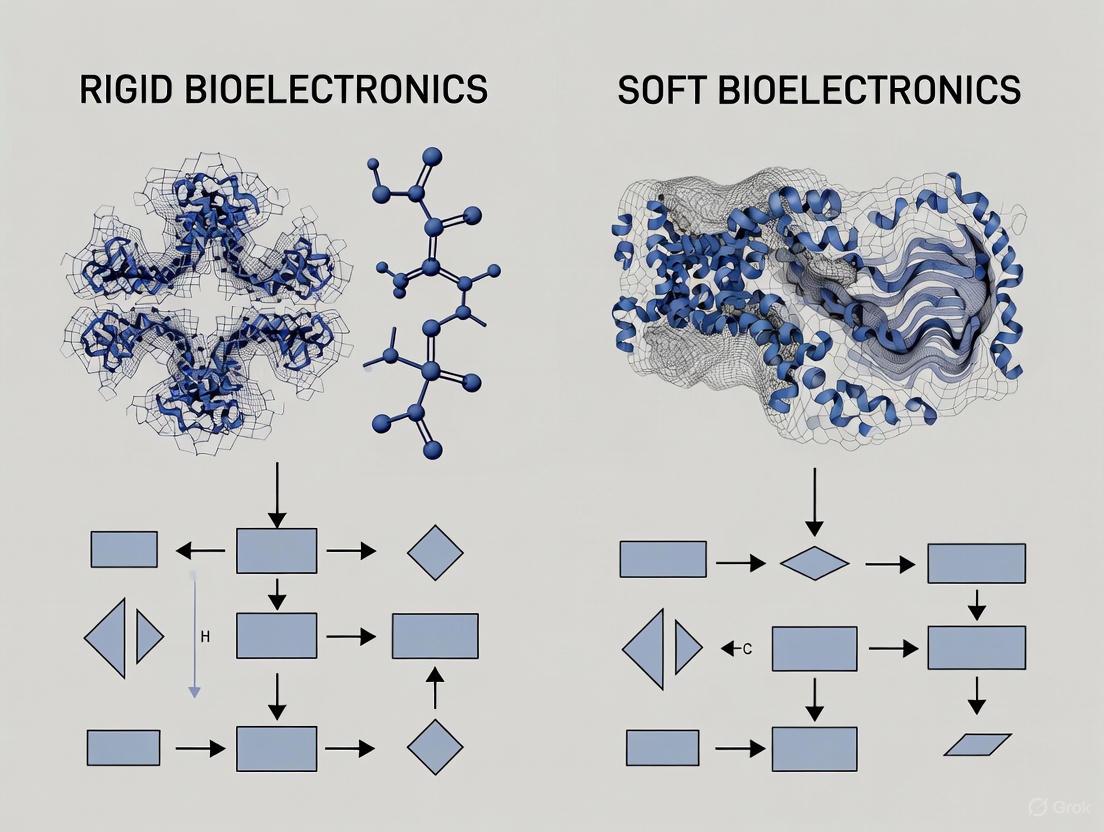

Workflow and Decision Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and decision-making process for selecting between rigid and soft bioelectronic paradigms based on application requirements.

The choice between rigid and soft bioelectronics is not merely a material selection but a fundamental design paradigm that dictates device performance and biocompatibility. Rigid bioelectronics, with their mature fabrication and robust interfaces, remain suitable for applications where mechanical mismatch is less critical. However, the future of bioelectronics, particularly for long-term, chronic, and patient-friendly interfaces, is unequivocally soft, flexible, and stretchable. The experimental data confirms that advanced soft materials can now achieve electrical performance on par with or superior to rigid standards, while simultaneously offering unparalleled mechanical compatibility. As research continues to enhance the durability, scalability, and multifunctionality of these soft systems, they are poised to become the dominant platform for next-generation wearable, implantable, and closed-loop bioelectronic medicines.

The field of bioelectronic medicine has undergone a profound transformation, shifting from rigid, bulky implants to soft, conformable systems that better integrate with biological tissues. This evolution represents a fundamental rethinking of how electronic devices interact with the living body, moving from a paradigm of mechanical dominance to one of mechanical compatibility.

Early bioelectronic implants were constructed from rigid materials like metals and silicon, which provided operational stability but created significant mechanical mismatch with soft, dynamic biological tissues [1]. This mismatch often led to inflammatory responses, tissue damage, and eventual device failure [10]. The recognition of these limitations spurred innovation in materials science and device engineering, leading to the development of soft bioelectronics that emulate the mechanical properties of biological tissues [11].

This comparison guide examines the performance differences between rigid and soft bioelectronic systems through the lens of historical evolution, providing researchers and drug development professionals with objective data on how this technological shift has impacted device functionality, longevity, and integration with biological systems.

Material Properties and Mechanical Compatibility

The core distinction between historical and contemporary bioelectronics lies in their fundamental material properties. Traditional implants utilized materials with mechanical characteristics drastically different from biological tissues, while modern approaches prioritize mechanical compatibility.

Table 1: Material Properties Comparison Between Rigid and Soft Bioelectronics

| Property | Rigid Bioelectronics | Soft & Flexible Bioelectronics |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Material Types | Silicon, metals, ceramics | Polymers, elastomers, hydrogels, thin-film materials, meshes [1] |

| Young's Modulus | > 1 GPa | 1 kPa – 1 MPa (typically) [1] |

| Bending Stiffness | > 10⁻⁶ N·m | < 10⁻⁹ N·m [1] |

| Device Thickness | > 100 µm | < 100 µm [1] |

| Stretchability | < 1% (brittle) | > 10% (> 100% for ultra-soft devices) [1] |

The mechanical mismatch between traditional rigid implants (Young's modulus > 1 GPa) and soft neural tissue (~1–30 kPa) is profound, differing by several orders of magnitude [11]. This discrepancy prevents rigid devices from conforming to biological substrates, leading to signal instability and physical damage to neural tissue during insertion and from tissue micromotion during indwelling [11].

Soft bioelectronics address this fundamental challenge through various innovative approaches. Hydrogels have emerged as ideal interface materials due to their high water content, low modulus, and excellent biocompatibility, bridging the gap between hard electronics and soft tissues [5]. Softening implantable bioelectronics represent another advanced strategy, utilizing stiffness-tunable materials that transition from an initial rigid state for surgical implantation to a softened state inside the body, combining the advantages of both rigid and soft devices [10].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

The transition from rigid to soft bioelectronics has produced measurable differences in device performance, particularly regarding tissue integration, signal fidelity, and long-term stability. The following experimental data, synthesized from multiple studies, illustrates these critical performance differences.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Rigid vs. Soft Bioelectronic Systems

| Performance Parameter | Rigid Bioelectronics | Soft Bioelectronics | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue Integration & Foreign Body Response | Stiffness mismatch causes inflammation and fibrotic encapsulation [1] | Soft, conformal materials match tissue mechanics and reduce immune response [1] | e-dura implant: No significant difference in activated astrocytes/microglia vs. sham after 6 weeks in rat spinal cords [11] |

| Chronic Signal Recording Stability | Long-term degradation due to micromotion and scar tissue [1] | Better chronic signal due to stable tissue contact [1] | NeuroGrid: Stable detection of single-cell action potentials from rat brain surface for up to 10 days [11] |

| Electrode-Tissue Interface Impedance | Increasing impedance over time due to fibrotic encapsulation | Stable low impedance due to conformal contact | PEDOT:PSS-based devices: Maintain lower impedance and enhanced charge transfer capability [11] |

| Mechanical Compliance in Dynamic Environments | Brittle under strain, poor strain tolerance [1] | Stretchable and bendable; can tolerate body movement [1] | Ultrathin neuron-like electrodes: Bending stiffness ~1.4–5.7×10⁻¹⁶ N·m², comparable to axons [11] |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Bioelectronic Performance

To generate the comparative data presented in Table 2, researchers employ standardized experimental protocols across several key domains:

Histological Analysis of Foreign Body Response:

- Methodology: Implants are surgically inserted into target tissues (e.g., brain cortex, spinal cord) of animal models. After predetermined intervals (e.g., 2, 6, 12 weeks), tissue is harvested, sectioned, and stained for immune cell markers (e.g., Iba1 for microglia, GFAP for astrocytes) [11].

- Quantification: Immunohistochemical images are analyzed to quantify the density and activation state of immune cells within a defined radius (e.g., 100 µm) from the implant-tissue interface. Reduced glial activation indicates improved biocompatibility.

- Application: This protocol was used to evaluate the e-dura spinal implant, which showed minimal immune activation comparable to sham surgery [11].

Electrophysiological Recording Stability Assessment:

- Methodology: Devices are implanted in relevant animal models (e.g., rodents, non-human primates). Neural signals (local field potentials, single-unit, multi-unit activity) are recorded periodically over weeks or months [11].

- Quantification: Signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and electrode impedance are tracked over time. The number of viable recording channels and amplitude of detectable neural signals are measured. Stable or improving metrics indicate better tissue integration.

- Application: NeuroGrid arrays demonstrated this capability by maintaining single-neuron resolution recordings from the cortical surface for extended periods [11].

Mechanical Compliance Testing:

- Methodology: The flexural rigidity of devices is quantified using cantilever bending tests or similar mechanical measurements. For in vivo validation, devices are subjected to simulated biological environments (cyclic stretching, immersion in physiological solutions) while monitoring electrical functionality [10].

- Quantification: Bending stiffness is calculated in N·m². Devices with values approaching neural structures (∼5.9–7.6×10⁻¹⁶ N·m² for axons) demonstrate superior mechanical compatibility [11].

Visualization of the Evolutionary Pathway

The transition from rigid to soft bioelectronics follows a logical progression driven by the need for improved integration and reduced foreign body response. The following diagram illustrates this evolutionary pathway and the key technological innovations at each stage.

Figure 1: The evolutionary pathway from rigid to soft bioelectronics, highlighting key technological developments at each stage. This progression addresses the fundamental challenge of mechanical mismatch through increasingly sophisticated material and design strategies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Developing and testing next-generation soft bioelectronics requires specialized materials and characterization tools. The following table details key research reagents and their functions in advancing soft, conformable bioelectronic systems.

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Soft Bioelectronics Development

| Material/Reagent | Category | Primary Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDMS (Polydimethylsiloxane) | Elastomer | Flexible substrate/encapsulation; provides mechanical compliance [11] | e-dura spinal implants, various flexible electrode arrays [11] |

| PEDOT:PSS | Conductive Polymer | Reduces electrode impedance; enhances charge injection capacity [11] | NeuroGrid surface electrodes, neural probe coatings [11] |

| Hydrogels | Polymer Network | Tissue-like interface material; high water content enables biocompatibility [5] | Soft bioelectronic interfaces, drug-eluting matrices [5] |

| Parylene-C | Polymer | Thin-film encapsulation and insulation; provides moisture barrier [11] | Flexible neural probes, implantable sensor coatings |

| Liquid Metal Alloys | Conductive Material | Stretchable conductors for extreme deformations [10] | Stretchable interconnects, soft circuit patterns |

| Silk Fibroin | Bioresorbable Polymer | Temporary stiffener for implantation; dissolves in body [10] | Sacrificial support layer for ultra-soft devices |

The historical evolution from rigid to soft, conformable bioelectronic systems represents a paradigm shift in how we interface technology with biological organisms. The performance data clearly demonstrates that soft bioelectronics offer significant advantages in reducing foreign body response, improving long-term signal stability, and enabling seamless integration with dynamic biological tissues.

While rigid implants provided the foundation for bioelectronic medicine and remain suitable for certain applications, the future direction of the field is firmly oriented toward soft, flexible, and intelligent material systems [1]. Emerging approaches—including biohybrid interfaces that incorporate living cellular components and "smart" encapsulation systems that respond to their biological environment—promise to further blur the boundary between artificial devices and natural tissues [11].

For researchers and drug development professionals, this evolutionary pathway offers important insights: success in bioelectronic medicine increasingly depends on addressing mechanical compatibility with the same rigor as electrical performance. The continued convergence of materials science, biology, and electrical engineering will undoubtedly yield even more sophisticated biointegrated systems capable of chronic, high-fidelity interaction with the nervous system and other electrically active tissues.

The interface between bioelectronic devices and biological tissues represents one of the most critical frontiers in medical technology development. The mechanical mismatch between conventional rigid electronic materials and soft, dynamic biological tissues poses a fundamental challenge that impacts device performance, tissue integration, and long-term stability [1] [12]. This mechanical disparity—where traditional electronics possess Young's moduli in the gigapascal range (≥1 GPa) while biological tissues such as neural tissue exhibit moduli in the kilopascal range (1-10 kPa)—creates a significant mechanical incompatibility that can lead to inflammation, fibrotic encapsulation, tissue damage, and eventual device failure [2] [13].

The evolution of bioelectronics has witnessed a paradigm shift from rigid to soft, compliant systems that better mimic the mechanical properties of biological tissues [1] [12]. This transition is driven by growing evidence that mechanical compatibility is equally as important as electrical performance for chronic implantation and reliable signal acquisition. While rigid implants like silicon-based Michigan probes and Utah arrays have enabled valuable neuroscientific discoveries, their stiff nature inevitably triggers foreign body responses that degrade signal quality over time through glial scar formation [2] [13]. The emerging generation of soft bioelectronics aims to overcome these limitations through innovations in materials science, structural design, and fabrication techniques that prioritize mechanical harmony with biological systems.

Quantitative Comparison: Rigid vs. Soft Bioelectronics

The performance differences between rigid and soft bioelectronics can be quantified across multiple parameters critical to long-term functionality. The table below summarizes key comparative metrics based on current research findings.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Rigid vs. Soft Bioelectronics

| Performance Parameter | Rigid Bioelectronics | Soft Bioelectronics | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Young's Modulus | >1 GPa (Silicon: ~10² GPa; Platinum: ~10² MPa) [2] [13] | 1 kPa - 1 MPa [1] | Material testing systems (e.g., tensile testers, nanoindenters) |

| Bending Stiffness | >10⁻⁶ Nm [1] | <10⁻⁹ Nm [1] | Cantilever bending tests, optical measurement of deformation |

| Chronic Signal Stability | Signal degradation over weeks/months due to inflammation and glial scarring [2] | Stable recording with <3% variation after 1000 bending cycles in DNA-based sensors [14] | Long-term electrophysiological recording in animal models |

| Inflammatory Response | Significant fibrotic encapsulation; chronic inflammation [2] [13] | Minimal immune response; reduced fibrotic encapsulation [1] [12] | Histological analysis (e.g., staining for astrocytes, microglia) |

| Tissue Integration | Poor integration due to stiffness mismatch; micromotion damage [2] | Conformal contact; seamless integration with tissues [1] [15] | Microscopy analysis of tissue-device interface |

| Stretchability | <1% (brittle) [1] | >10% (>100% for ultra-soft devices) [1] | Uniaxial/tensile strain testing |

| Electrical Performance under Deformation | Performance degradation or failure under strain | Maintains conductivity even at >1,200% strain for liquid metal devices [16] | Resistance measurement during mechanical deformation |

Material Strategies and Structural Designs for Mechanical Compatibility

Advanced Material Solutions

Innovative materials form the foundation of next-generation soft bioelectronics. Liquid metal-based composites, particularly gallium-based alloys, have emerged as promising conductors due to their exceptional deformability while maintaining high electrical conductivity. Recent research has demonstrated liquid metal circuits patterned with micrometer-scale precision that maintain consistent electrical performance even when stretched by more than 1,200% [16]. The combination of colloidal self-assembly and micro-transfer printing enables the creation of these highly precise and stretchable electronic networks that conform seamlessly to biological tissues [16].

Porous architectures represent another strategic approach to enhancing mechanical compatibility and biological integration. These structures facilitate bidirectional communication between human organs and their surrounding microenvironments by allowing sweat evaporation, heat dissipation, moisture transport, and biochemical diffusion [15]. Fabrication techniques such as electrospinning produce nanofiber substrates with high porosity, gas permeability, and minimal bending stiffness, enabling conformal contact with curvilinear biological surfaces without impeding natural processes like wound healing [14] [15]. These porous conductive materials can be synthesized through both top-down approaches (laser engraving, etching, photolithography) and bottom-up approaches (electrospinning, 3D printing, phase separation) [15].

Structural Engineering Innovations

Beyond material composition, structural design plays a crucial role in achieving mechanical compatibility. Serpentine patterns, mesh structures, and kirigami/origami-inspired designs enable otherwise non-stretchable materials to accommodate significant deformation [6]. These engineered structures allow conventional conductive materials like gold and platinum to be incorporated into stretchable devices without compromising electrical performance [6].

The integration of nanomesh electrodes and island-bridge architectures further enhances mechanical compliance while maintaining reliable electrical functionality. In island-bridge designs, rigid functional components (islands) are interconnected with stretchable conductors (bridges), localizing strain to the compliant interconnects while protecting active elements from mechanical stress [3]. This approach enables the incorporation of semiconductor devices that would otherwise be incompatible with soft, deformable systems.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Tissue-Device Interface

Mechanical Compliance Testing

Protocol 1: Bending Stiffness Measurement

- Objective: Quantify the flexibility of bioelectronic devices to evaluate their compatibility with dynamic biological tissues.

- Methodology:

- Fabricate devices on substrates of varying thickness (typically <100 μm for flexible devices) [1]

- Mount samples as cantilevers and apply controlled forces at free ends

- Measure deflection using optical methods (e.g., laser displacement sensors)

- Calculate bending stiffness (D) using the formula: D = E×I, where E is Young's modulus and I is the second moment of area

- Key Parameters: Device thickness, elastic modulus of constituent materials, neutral mechanical plane position

- Validation: Ultrathin devices (<10 μm) demonstrate bending stiffness below 10⁻⁹ Nm, enabling van der Waals-driven conformal contact without adhesives [3]

Protocol 2: Cyclic Strain Testing

- Objective: Evaluate device performance under repeated deformation mimicking natural body movements.

- Methodology:

- Mount devices on stretchable substrates or mechanical testers

- Apply cyclic strain (typically 10-30% for skin-worn devices, higher for cardiac applications)

- Monitor electrical continuity, impedance, and signal quality throughout cycles

- Perform microscopic analysis to identify mechanical failure points

- Endpoint Analysis: Devices should maintain functionality with <5% variation in electrical properties after thousands of cycles [14]

Biological Integration Assessment

Protocol 3: Histological Evaluation of Foreign Body Response

- Objective: Quantify tissue reaction to implanted devices and correlate with mechanical properties.

- Methodology:

- Implant devices in animal models (typically rodents for neural interfaces)

- After predetermined periods (2, 4, 8, 12 weeks), perfuse and section tissue

- Stain for astrocytes (GFAP), microglia (Iba1), and neurons (NeuN)

- Quantify cell densities and distribution relative to implant site

- Metrics: Fibrotic capsule thickness, neuronal density in proximity, activation state of immune cells

- Findings: Rigid implants typically show 50-100 μm fibrotic encapsulation with significant neuronal loss, while soft devices exhibit minimal encapsulation [2] [13]

Protocol 4: Chronic Electrophysiological Recording Stability

- Objective: Assess long-term signal acquisition capabilities in functioning systems.

- Methodology:

- Implant recording devices in relevant brain regions

- Record neural signals (single-unit, multi-unit, local field potentials) regularly over months

- Track signal-to-noise ratio, unit yield, and amplitude stability

- Correlate electrophysiological changes with histological findings

- Validation: Soft neuroprobes maintain stable single-unit recording for >6 months, while rigid devices typically show significant signal degradation within weeks [2]

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Tissue-Device Interface Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Metal (Ga-based alloys) | Deformable conductor | Stretchable interconnects, conformal electrodes [16] |

| PEDOT:PSS | Conductive polymer | Organic electrochemical transistors (OECTs), low-impedance coatings [3] |

| Electrospun PAN/TPU nanofibers | Porous substrate | Breathable biosensing patches, wound monitoring [14] |

| Tetrahedral DNA (TDNA) | Mechanically stable biosensing element | Protein detection with reduced biofouling [14] |

| Carbon nanotubes/Graphene | Conductive nanomaterial | Strain sensors, transparent electrodes [6] |

| Self-healing polymers | Autonomous damage repair | Extended device longevity in dynamic environments [6] |

| Hydrogels | Hydrated, tissue-mimicking matrix | Injectable electronics, drug-eluting interfaces [1] |

Signaling Pathways in Foreign Body Response

The biological response to implanted devices follows a complex cascade of signaling events that initiate with mechanical mismatch and culminate in functional isolation of the device. The diagram below illustrates key pathways in this process.

Diagram 1: Foreign Body Response Signaling Pathways. The diagram contrasts the biological responses triggered by mechanically mismatched devices (red/orange) versus soft, compliant interfaces (green).

Application-Specific Performance Analysis

Neural Interfaces

The impact of mechanical mismatch is particularly pronounced in neural interfacing applications, where devices must integrate with exceptionally soft and sensitive tissues. Conventional rigid neural probes (Young's modulus ~10² GPa) create a significant mechanical mismatch with brain tissue (Young's modulus ~1-10 kPa), leading to chronic inflammation, glial scarring, and signal degradation over time [2] [13]. The foreign body response begins with immediate tissue damage during insertion, followed by persistent micromotion-induced inflammation as the device moves within the brain parenchyma. This triggers activation of microglia and astrocytes, creating a protective but electrically insulating glial scar that progressively isolates the electrode from nearby neurons, diminishing recording quality and stimulation efficacy [13].

In contrast, flexible neural probes fabricated from compliant polymers or ultra-thin silicon demonstrate significantly reduced foreign body responses. Devices with bending stiffness below 10⁻⁹ Nm promote minimal astrocyte activation and maintain proximity to neurons, enabling stable single-unit recording over extended periods [2]. Advanced approaches include mesh electronics that seamlessly integrate with neural tissue through designed porosity and mechanical properties matching the extracellular matrix. These systems have demonstrated reliable tracking of the same individual neurons for over a year, far surpassing the capabilities of rigid interfaces [2].

Cardiac Monitoring and Stimulation

The dynamic nature of cardiac tissue presents unique challenges for bioelectronic interfaces. Traditional cardiac catheters and pacemakers utilize relatively rigid components that can cause tissue damage, particularly in continuously contracting heart muscle. Recent innovations in soft bioelectronics address these limitations through compliant designs that maintain stable contact during cardiac cycles.

Instrumented balloon catheters integrated with liquid metal microelectrode arrays represent a significant advancement in this domain. These devices can expand without compromising electrical conductivity, providing high-resolution maps of cardiac electrical activity during procedures such as ablation therapy [16]. Laboratory and animal tests demonstrate that these compliant systems maintain low electrical impedance while conforming to the endocardial surface, offering more detailed electrophysiological data than conventional rigid catheters [16]. The enhanced contact stability improves signal quality and enables more precise identification of arrhythmic substrates.

Chronic Wound Monitoring

The monitoring of chronic wounds requires specialized biointerfaces that can conform to irregular wound beds without impeding the healing process. Traditional rigid sensors often hinder exudate management and gas exchange, potentially exacerbating wound complications. Soft, breathable biosensing patches address these limitations through porous nanofiber substrates that permit moisture vapor transmission while maintaining conformal contact [14].

Advanced wound monitoring platforms incorporate both biophysical sensors (temperature, pH, impedance) and biochemical sensors for detecting low-abundance protein biomarkers indicative of healing status. The integration of self-confined tetrahedral DNA circuits (SCTD) enables sensitive detection of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6) and growth factors (TGF-β1, VEGF) with minimal signal attenuation (<8% over 4 weeks) despite mechanical deformation [14]. These systems demonstrate mechanical stability within 3% variation after 1000 bending cycles, making them suitable for monitoring wounds over articulating joints or other dynamic areas [14].

The critical role of mechanical matching at the tissue-device interface is now unequivocally established, driving a fundamental shift toward soft, compliant bioelectronic systems. Quantitative evidence demonstrates that mechanical compatibility directly correlates with improved signal stability, reduced foreign body response, and extended functional longevity across diverse applications from neural interfaces to cardiac monitoring and wound management. The ongoing development of novel materials—including liquid metal composites, conductive polymers, and porous architectures—combined with innovative structural designs continues to advance the capabilities of soft bioelectronics.

Future research directions will likely focus on further enhancing the biological integration of these devices through biohybrid approaches incorporating living cellular components, dynamic materials capable of adapting their properties in response to physiological changes, and increasingly sophisticated closed-loop systems that combine monitoring and therapeutic intervention. As the field progresses, standardized methodologies for assessing mechanical compatibility and biological response will become increasingly important for comparative evaluation of emerging technologies. The ultimate convergence of materials science, biology, and engineering will enable a new generation of bioelectronic medicines that seamlessly interface with the human body, transforming the management of chronic diseases and neurological disorders.

Inherent Advantages and Limitations of Each Approach

The field of bioelectronic medicine leverages miniaturized electronic devices to interface with the body's electrically active tissues, offering innovative therapeutic solutions distinct from traditional pharmaceuticals [1]. A central paradigm in the development of these devices is the choice between rigid and soft material platforms. Conventional bioelectronics have primarily been constructed from rigid materials such as metals and silicon, valued for their mechanical stability and robust electrical performance [10]. However, the inherent mechanical mismatch between these stiff devices and soft, dynamic biological tissues often leads to complications, including inflammation, scar tissue formation, and long-term signal degradation [2] [17].

In response, the field has seen a significant shift toward soft and flexible bioelectronics, which aim to emulate the mechanical properties of biological tissues [1] [10]. This review provides a structured, objective comparison of these two approaches, dissecting their inherent advantages and limitations. By synthesizing current research and experimental data, we aim to offer researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals a clear framework for selecting the appropriate material platform for specific biomedical applications, from neural interfacing and cardiac pacemaking to wearable health monitoring.

Performance Comparison: Rigid vs. Soft Bioelectronics

The fundamental differences in material composition between rigid and soft bioelectronics directly translate to distinct performance characteristics in biological environments. The table below summarizes a comparative analysis of their key properties.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Rigid and Soft Bioelectronics

| Property | Rigid Bioelectronics | Soft Bioelectronics |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Material Types | Silicon, metals, ceramics [1] | Polymers, elastomers, hydrogels, thin-film materials, meshes [1] [17] |

| Young's Modulus | > 1 GPa [1] | 1 kPa – 1 MPa (typically) [1] |

| Bending Stiffness | > 10⁻⁶ Nm [1] | < 10⁻⁹ Nm [1] |

| Stretchability | < 1% (brittle) [1] | > 10% (> 100% for ultra-soft devices) [1] |

| Tissue Integration & Biocompatibility | Disadvantage: Stiffness mismatch causes inflammation and fibrotic encapsulation [1] [2] | Advantage: Soft, conformal materials match tissue mechanics and reduce immune response [1] [10] |

| Chronic Signal Fidelity | Disadvantage: Long-term degradation due to micromotion and scar tissue [1] [2] | Advantage: Better chronic signal due to stable tissue contact and reduced scarring [1] [7] |

| Implantation & Surgical Handling | Advantage: Rigid housing eases handling during implantation [1] [10] | Disadvantage: May require new surgical techniques or temporary stiffeners [1] [10] |

| Power/Data Interfaces | Advantage: Mature, robust wired and wireless interface options [1] | Disadvantage: Interfaces can be less robust; an area of ongoing development [1] |

Experimental Protocols for Performance Validation

To quantitatively compare the performance of rigid and soft bioelectronics, researchers employ standardized experimental protocols. The workflows below outline two critical tests for evaluating bioelectronic devices.

Protocol for Electrode-Tissue Interface Impedance

Electrode-tissue interface impedance is a critical metric for assessing signal acquisition quality and stimulation efficiency. Lower impedance is generally associated with better signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) for recording and more efficient charge transfer for stimulation [7].

Protocol for Chronic In Vivo Biocompatibility

Assessing the chronic foreign body response is essential for evaluating the long-term stability and safety of an implant. The formation of fibrotic scar tissue around an implant can severely compromise its function [1] [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The development and testing of bioelectronics rely on a specialized set of materials and reagents. The following table details essential items used in the featured experiments and broader field research.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bioelectronics Development

| Reagent/Material | Function & Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS | An intrinsically conductive polymer used to create conductive hydrogels for neural interfaces [17]. | High conductivity (~40 S/cm to 670 S/cm), biocompatible, can form soft hydrogels with low Young's modulus [17]. |

| Liquid Metals (e.g., Ga-based) | Used to create stretchable and self-healing electrodes for wearable and implantable devices [7] [10]. | High conductivity, fluidic at room temperature, enabling extreme stretchability and conformability to skin [7]. |

| Conductive Hydrogel Nanocomposites | Soft, tissue-like materials for implantable electrodes, combining hydrogels with conductive nanofillers [17]. | Tissue-mimetic softness (kPa-MPa range), ionic/electronic conductivity, often biodegradable and bioadhesive [17]. |

| Silicon (for Michigan/Utah probes) | The primary material for conventional rigid microelectrode arrays for high-density neural recording [2]. | Rigid and brittle (GPa modulus), enables high-resolution lithography, excellent short-term signal fidelity [1] [2]. |

| Ag/AgCl Electrodes | The clinical gold standard for gel-based skin electrodes, used as a benchmark in experimental protocols [7]. | Stable electrochemical potential, low noise; used as a reference for normalizing SNR and impedance data [7]. |

| Stiffness-Tunable Polymers | Polymers (e.g., PLGA, silk fibroin) used in "softening" implants that are rigid for insertion but soften in the body [10]. | Wide, tunable stiffness range (MPa to kPa); degrade or hydrate in response to bodily fluids [10]. |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The dichotomy between rigid and soft bioelectronics is being bridenced by innovative hybrid and adaptive technologies. One promising direction is the development of softening implantable bioelectronics that transition from a rigid state for easy surgical handling to a soft state post-implantation for enhanced biocompatibility [10]. These devices use materials like PLGA or silk fibroin that degrade, or hydrogels that swell, upon exposure to bodily fluids, dynamically reducing their modulus from GPa to kPa ranges [10].

Another frontier is the creation of multifunctional and "living" bioelectronic interfaces [2]. These systems integrate electrical recording with other modalities like optical stimulation and chemical sensing, providing a more comprehensive view of neural circuit dynamics. Furthermore, biohybrid systems that incorporate living cells or biological components within conductive scaffolds are being explored for their potential to promote neural regeneration and achieve seamless, synaptically connected integration with host tissue [2].

Despite rapid progress, challenges in manufacturing scalability, long-term encapsulation, and power management remain active areas of research [1] [7]. The continued convergence of materials science, biology, and electrical engineering will be crucial in developing next-generation bioelectronics that are not only high-performing but also stable, safe, and fully integrated with the human body for chronic applications.

The Trajectory Towards Tissue-Like Electronics

The field of bioelectronics is undergoing a fundamental transformation, moving away from rigid, bulky devices toward soft, tissue-like electronics that seamlessly integrate with biological systems. This paradigm shift is driven by the critical need to overcome the mechanical mismatch between conventional electronic materials and the soft, dynamic tissues of the human body [1]. Early bioelectronic implants, such as pacemakers and deep brain stimulators, were constructed from rigid materials like silicon and metals. While effective, their stiffness often led to patient discomfort, inflammatory responses, fibrotic encapsulation, and eventual device failure over time [1] [18].

The human body is composed of soft, curvilinear, and continuously moving tissues, making it critical for implanted and wearable devices to conform and integrate seamlessly with their biological environment [1]. This review objectively compares the performance of rigid bioelectronics against emerging soft, tissue-like alternatives, focusing on quantitative metrics essential for researchers and drug development professionals. We examine material strategies, experimental data on device performance, and detailed methodologies shaping the next generation of biomedical technologies, framing this progress within the broader thesis of rigid versus soft bioelectronics performance comparison research.

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Analysis of Rigid vs. Soft Bioelectronics

The performance disparity between traditional rigid bioelectronics and emerging soft alternatives can be quantified across multiple mechanical, electrical, and biological parameters. The tables below summarize key comparative data from recent studies.

Table 1: Material and Mechanical Property Comparison between Rigid and Soft Bioelectronics

| Property | Rigid Bioelectronics | Soft & Flexible Bioelectronics | Performance Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Young's Modulus | > 1 GPa [1] | 1 kPa – 1 MPa (typically) [1] | Soft devices match tissue mechanics, reducing immune response. |

| Bending Stiffness | > 10-6 Nm [1] | < 10-9 Nm [1] | Ultralow stiffness enables conformal contact without irritation. |

| Typical Device Thickness | > 100 µm [1] | < 100 µm [1] | Sub-100 µm thickness is critical for van der Waals-driven skin adhesion. |

| Stretchability | < 1% (brittle) [1] | > 10% (> 1000% for some liquid metal devices) [1] [16] | High stretchability allows operation on dynamic organs (heart, skin, intestines). |

| Typical Materials | Silicon, metals, ceramics [1] | Polymers, elastomers, hydrogels, liquid metals, thin-film meshes [1] [16] [19] | Material choice directly influences biocompatibility and device integration. |

Table 2: Functional Performance and Biocompatibility Metrics

| Parameter | Rigid Bioelectronics | Soft & Flexible Bioelectronics | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic Signal Stability | Long-term degradation due to micromotion and scar tissue [1] | Better chronic signal due to stable tissue contact [1] | Neural recording; soft devices maintain stable single-neuron recording for up to 4 months [20]. |

| Tissue Damage & Inflammation | High risk due to stiffness mismatch [1] [3] | Significantly reduced inflammatory and immune responses [3] | Histological analysis post-implantation shows minimal fibrosis for soft devices. |

| Electrical Conductivity under Strain | Conductivity lost upon fracture | Maintains conductivity even when stretched >1200% [16] | Liquid metal-based stretchable electronics [16]. |

| Adhesion to Tissue | Requires sutures or anchors; poor innate adhesion. | Strong, conformal adhesion via van der Waals forces or bioadhesives [6] [3] | Ultrathin devices (<5 µm) achieve adhesion through van der Waals forces alone [3]. |

| Long-Term Operational Stability | Limited by fibrotic encapsulation and mechanical failure [1] | Demonstrated stability for over 43 weeks in animal models [20] | Injectable and implantable flexible fibres for bioelectrical monitoring [20]. |

The data reveals a clear trajectory: soft bioelectronics significantly outperform rigid counterparts in mechanical compatibility, long-term signal stability, and biocompatibility. The fundamental advantage lies in minimizing the modulus mismatch with native tissues, which can reduce interfacial stress and strain by over 80% through optimized energy dissipation mechanisms [19]. This mechanical harmony is a prerequisite for chronic device stability and high-fidelity signal acquisition.

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Bioelectronic Performance

Validating the performance of tissue-like electronics requires rigorous, standardized experimental protocols. Below are detailed methodologies for key evaluations cited in this field.

Protocol 1: In Vivo Testing of Long-Term Stability and Biocompatibility

This protocol assesses the chronic performance and tissue response of implantable bioelectronic devices [20] [3].

- Objective: To evaluate the long-term signal fidelity, device stability, and histological tissue response of an implanted soft bioelectronic device over a period of several months.

- Materials:

- Test Device: Soft bioelectronic device (e.g., rolled-up fibre, hydrogel electrode).

- Animal Model: Rodents (e.g., mice or rats) or larger animals (e.g., pigs) as appropriate.

- Surgical equipment for sterile implantation.

- Data Acquisition System: For recording electrophysiological signals (e.g., neural spikes, local field potentials, ECG).

- Materials for Histology: Fixatives (e.g., paraformaldehyde), cryostat, staining agents (e.g., H&E for general morphology, immunofluorescence for specific cell markers like CD68 for macrophages).

- Procedure:

- Implantation: Surgically implant the test device into the target tissue (e.g., brain, heart, peripheral nerve) under approved anesthetic and analgesic protocols.

- Signal Recording: At regular intervals (e.g., weekly), connect the device to the data acquisition system and record target biosignals (e.g., signal-to-noise ratio of neural spikes, amplitude of ECG signals).

- Termination and Extraction: At predetermined endpoints (e.g., 4 weeks, 12 weeks, 43+ weeks), euthanize the animal and carefully extract the device along with the surrounding tissue.

- Histological Analysis:

- Fix the tissue sample for 24-48 hours.

- Process, embed, and section the tissue.

- Stain sections with H&E and relevant immunofluorescence markers.

- Image the tissue-device interface to quantify fibrotic capsule thickness and immune cell infiltration.

- Data Analysis: Compare signal quality metrics over time and correlate with histological findings. A stable signal-to-noise ratio and minimal fibrotic encapsulation indicate superior performance.

Protocol 2: Electro-Mechanical Characterization of Stretchable Conductors

This protocol quantitatively measures the electrical performance of conductive materials under mechanical deformation, a critical test for wearable and implantable sensors [16] [6].

- Objective: To characterize the resistance change of a stretchable conductive element (e.g., liquid metal microelectrode, conductive hydrogel) under uniaxial tensile strain.

- Materials:

- Sample: Fabricated stretchable conductor.

- Universal Testing Machine (UTM) equipped with a tensile stage.

- Digital Source Meter or LCR Meter.

- Custom fixtures to electrically connect the sample to the meter while stretched.

- Procedure:

- Setup: Mount the sample onto the UTM and connect its ends to the source meter using non-destructive clamps.

- Baseline Measurement: Measure the initial resistance (R0) of the sample at 0% strain.

- Strain Cycling: Program the UTM to apply a specific strain cycle (e.g., 0% to 50% strain and back, or a more extreme 0% to 1200% strain [16]).

- Simultaneous Monitoring: Continuously or at fixed strain intervals, record the sample's resistance (R) and the applied strain (ε) throughout the cycle.

- Repeat: Perform multiple cycles to assess fatigue and recovery.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the normalized resistance change (ΔR/R0). Plot ΔR/R0 against strain (ε). A minimal change in resistance, even at high strains, indicates excellent electro-mechanical stability, a hallmark of advanced materials like liquid metals.

Protocol 3: Evaluation of Conformal Contact and Signal Fidelity on Skin

This protocol tests the performance of wearable epidermal electronics [3].

- Objective: To compare the quality of electrophysiological signals (e.g., ECG, EMG) acquired by a rigid electrode, a flexible electrode, and an ultrathin, conformal electrode during subject movement.

- Materials:

- Electrode Types: (a) Standard rigid Ag/AgCl gel electrode, (b) Flexible Au/PET electrode, (c) Ultrathin electronic tattoo (e.g., graphene-based or nanomesh electrode).

- Biopotential Amplifier with multiple channels.

- Motion Tracking System or accelerometer.

- Procedure:

- Application: Apply the three different electrode types adjacently to the same skin site (e.g., chest for ECG, forearm for EMG).

- Data Recording:

- Record baseline signals while the subject is stationary.

- Instruct the subject to perform controlled movements (e.g., walking, jogging, flexing muscles).

- Simultaneously record the electrophysiological signals and motion data.

- Analysis: Calculate the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and identify motion artifacts in the recorded signals for each electrode type during both static and dynamic phases.

- Data Analysis: Ultrathin, conformal electrodes are expected to show significantly higher SNR and fewer motion artifacts during movement due to their superior skin-contact stability, preventing detachment and minimizing motion-induced noise.

Visualization: Material and Performance Relationships in Tissue-Like Electronics

The development of high-performing soft bioelectronics relies on the interplay between material innovation, structural design, and resulting device properties. The following diagram illustrates this logical workflow and the key performance advantages it enables.

Material-Driven Performance Workflow - This diagram illustrates the logical pathway from material and structural choices to the key performance advantages of tissue-like electronics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The advancement of tissue-like electronics relies on a specific toolkit of innovative materials and reagents. The following table details key solutions and their functions for researchers in this field.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Developing Soft Bioelectronics

| Material/Reagent | Category | Key Function & Properties | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Metals (e.g., EGaIn) | Conductive Element | Extraordinary stretchability (>1200%) and stable conductivity under deformation; can be patterned at micrometer scale [16]. | Stretchable interconnects, balloon catheter microelectrode arrays for cardiac mapping [16]. |

| 2D Materials (e.g., Graphene, MXenes) | Conductive Element | Atomically thin, high electrical conductivity, optical transparency, and mechanical flexibility [18]. | Epidermal electronic tattoos for electrophysiological monitoring, transparent electrodes for OECTs [6] [18]. |

| Biomaterial-Based Hydrogels (Gelatin, Chitosan, Alginate) | Soft Substrate / Conductor | Tissue-matching Young's modulus, inherent biocompatibility, ionic conductivity; can be engineered with self-healing and adhesive properties [19]. | Wearable strain sensors, injectable bioelectronics, interfaces for electrophysiological signal recording and stimulation [19]. |

| Alvetex Advanced Scaffold | 3D Cell Culture Platform | Provides a porous polystyrene scaffold to engineer more physiologically relevant 3D tissue models in vitro for device testing [21]. | Creating human skin equivalents for pre-clinical testing of wearable and implantable bioelectronic devices. |

| PEDOT:PSS | Conductive Polymer | High conductivity for a polymer, biocompatibility, mixed ionic-electronic conductivity ideal for interfacing with biological tissues [3]. | Active layer in Organic Electrochemical Transistors (OECTs) for signal amplification in flexible biosensors [3]. |

| Parylene-C | Substrate/Encapsulation | Biocompatible polymer used as an ultrathin (<5 µm), flexible, and conformal substrate and protective encapsulation layer [3]. | Substrate for ultraflexible and implantable neural interfaces and epidermal electronic systems [3]. |

The trajectory towards tissue-like electronics is unequivocally charting a course away from the rigid, mechanically mismatched platforms of the past. Quantitative performance comparisons reveal that soft bioelectronics, engineered through innovations in materials and structural design, consistently outperform rigid devices in critical areas: achieving mechanical harmony with biological tissues, maintaining stable, high-fidelity signals over chronic timescales, and minimizing adverse immune responses. While challenges in large-scale manufacturing and long-term in vivo stability persist, the experimental data and protocols outlined provide a roadmap for continued progress. For researchers and drug development professionals, the adoption of these soft, conformal systems promises not only more reliable and comfortable devices for patients but also more accurate and predictive models for therapeutic development and testing. The future of bioelectronics is undoubtedly soft.

Engineering the Future: Material Innovations and Applications in Soft Bioelectronics

Conventional bioelectronic systems, typically constructed from rigid materials like silicon and metals, suffer from a fundamental mechanical mismatch with soft biological tissues. This incompatibility often leads to adverse effects such as inflammation, reduced signal transmission efficiency, and challenges in achieving stable long-term bio-integration [22]. The emergence of soft electronic materials—specifically organic semiconductors, hydrogels, and conductive polymers—represents a transformative approach to bridging this biotic-abiotic divide. These materials combine the advanced electronic functionalities of traditional semiconductors with the soft, deformable, and biocompatible properties of biological tissues, enabling a new generation of bio-integrated devices.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of these three material classes, focusing on their performance characteristics, applications, and experimental methodologies within bioelectronics research. The shift toward these soft materials is driven by the need for devices that can form conformal contact with complex tissue surfaces, minimize mechanical mismatch, and facilitate stable adhesion—all critical factors for enhancing the fidelity of signal acquisition in sensing applications and mitigating the foreign-body response [22].

Comparative Performance Analysis

The selection of materials for soft bioelectronics requires careful consideration of electronic, mechanical, and biological properties. The table below provides a quantitative comparison of key performance metrics for organic semiconductors, hydrogels, and conductive polymers.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Soft Electronic Materials

| Material Class | Charge Carrier Mobility (cm² V⁻¹ s⁻¹) | Young's Modulus | Stretchability | Key Strengths | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Semiconductors | Up to 1.4 (in hydrogel composites) [23] | Not specified in results | Not specified in results | • Rich electronic/optoelectronic functions (signal amplification, photoexcitation) [23] • Flexibility [24] | • Environmental sensitivity (moisture, oxygen) [24] • Limited durability [24] |

| Hydrogels | Not primarily conductive (except specialized composites) | 1 kPa - 100 kPa (tissue-like) [22] | High (e.g., 569% elongation) [22] | • Superior biocompatibility & tissue integration [22] • Tunable mechanical properties [22] | • Low electrical conductivity (native) • Environmental sensitivity (dehydration) [22] |

| Conductive Polymers | Varies with doping and type | Not specified in results | Not specified in results | • High electrical conductivity • Mechanical flexibility [25] • Ease of processing [26] | • Limited biocompatibility for some types [25] • Mechanical rigidity vs. tissues [25] |

Detailed Material Profiles and Experimental Methodologies

Organic Semiconductors

Material Profile: Organic semiconductors are carbon-based compounds, including small molecules (e.g., pentacene, rubrene) and polymers (e.g., P3HT, polyfluorenes), that possess semiconducting properties [27]. They are pivotal in applications such as organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs), organic photovoltaics (OPVs), and organic field-effect transistors (OFETs) [24]. Their key advantage lies in enabling flexible, lightweight, and cost-effective electronic devices, which are ideal for wearable health monitors and implantable sensors [24].

Experimental Protocol: Fabrication of Hydrogel-Semiconductor Composites (hydro-SC)

A groundbreaking methodology for creating ultra-soft semiconducting hydrogels with high electronic performance has been recently developed [23].

- Solution Preparation: A mixed solution is prepared using a polymer semiconductor (e.g., p(g2T-T)) and a hydrogel-forming monomer (e.g., Acrylic Acid, AAc) in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). A crosslinker and photoinitiator are added.

- Film Casting and Gelation: The solution is spin-coated or cast onto a substrate. UV-crosslinking is performed to form a 3D network of the hydrogel polymer within the DMSO solvent, creating an organogel.

- Solvent Exchange: The DMSO-swollen gel is immersed in water, exchanging the solvent. The polymer semiconductor, insoluble in water, precipitates and assembles into a percolated network within the porous hydrogel framework, forming the final hydro-SC.

- Device Fabrication and Characterization: The resulting hydro-SC can function as the channel layer in Organic Electrochemical Transistors (OECTs). Electrical performance is characterized by measuring charge-carrier mobility and transconductance, while mechanical properties like Young's modulus are assessed via tensile testing [23].

Hydrogels

Material Profile: Hydrogels are three-dimensional networks of hydrophilic polymers that can absorb and retain large amounts of water or biological fluids [28]. Their exceptional biocompatibility, tissue-like mechanical properties (modulus tunable from 1 to 100 kPa), and high water content make them ideal for bio-integration [22]. While naturally insulating, their functionality can be expanded by creating composites with conductive materials.

Experimental Protocol: Fabrication of a Dual-Network Conductive Hydrogel

A representative protocol for creating a mechanically robust and conductive hydrogel involves a one-pot method using a binary solvent system [22].

- Polymer Dissolution: Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) is dissolved in a mixed solvent of glycerol (GL) and water. Gelatin is then added to the mixture to form a dual-network precursor.

- Gel Formation: The mixture is injected into molds and subjected to a freeze-thaw cycle (e.g., -20°C to 25°C) to physically crosslink the PVA via microcrystalline formation.

- Mechanical and Electrical Tuning: The mechanical strength and elasticity can be tuned by adjusting the glycerol content, which influences hydrogen bonding. Electrical conductivity can be imparted by incorporating ionic crosslinkers like Fe³⁺ ions during synthesis. The concentration of Fe³⁺ can be varied to optimize both electrical conductivity and mechanical toughness [22].

- Performance Testing: The resulting hydrogel's tensile strength, elongation at break, and toughness are measured. Electrical performance can be demonstrated by testing its ability to complete a simple circuit, such as powering an LED [22].

Conductive Polymers

Material Profile: Conductive polymers are organic polymers with a conjugated π-electron backbone that, upon doping, exhibit significant electrical conductivity [25]. Key examples include poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT), polypyrrole (PPy), and polyaniline (PANI) [25]. They combine the electronic properties of metals with the processing advantages and flexibility of plastics, making them widely used in biosensing, neural interfaces, and energy storage [25].

Experimental Protocol: Creating an Injectable Conductive Polymer Formulation for Drug Delivery

Recent advances allow conductive polymers to be formulated for minimally invasive delivery and seamless tissue integration [25].

- Polymer Synthesis and Functionalization: A conductive polymer like PPy or PEDOT is synthesized or obtained commercially. To improve biocompatibility and processability, it may be chemically functionalized or blended with biocompatible polymers (e.g., PSS for PEDOT:PSS).

- Formulation for Injectability: The conductive polymer is processed into an injectable form. This can involve creating a suspension of polymer nanoparticles in a biocompatible aqueous buffer or formulating a conductive hydrogel composite that is shear-thinning.

- Drug Loading: Therapeutic agents or biomolecules are loaded into the polymer matrix. This can be achieved through absorption, electrochemical entrapment during synthesis, or covalent attachment.

- Stimulation-Triggered Release: The loaded formulation is injected into the target tissue. The release of the therapeutic agent is triggered by applying an electrical stimulus. The resulting current or redox state change in the polymer induces the controlled release of the drug, enabling localized and on-demand therapy [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Soft Bioelectronics Research

| Item | Function/Application | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Semiconductors | Forms the active semiconductor layer in transistors and sensors [23]. | p(g2T-T), Poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT) [27] [23] |

| Hydrogel Forming Monomers/Polymers | Creates the hydrophilic, soft matrix for bio-integration [22] [23]. | Acrylic Acid (AAc), Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA), Gelatin, Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) [22] [23] |

| Conductive Polymers | Provides electrical conductivity for electrodes, sensors, and stimulation [25]. | PEDOT:PSS, Polypyrrole (PPy), Polyaniline (PANI) [25] |

| Crosslinkers | Stabilizes the 3D network of hydrogels and composites. | N,N'-Methylenebis(acrylamide), Fe³⁺ ions [22] |

| Biocompatible Solvents | Processing medium for material synthesis and fabrication. | Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO), Water [23] |

| Dopants | Enhances the electrical conductivity of conjugated polymers. | Choline chloride, Tosylate ions [25] |

Research Workflow and Material Interrelationships

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for developing and characterizing a soft bioelectronic material, such as a hydrogel-semiconductor composite, integrating the key protocols and characterization steps outlined in this guide.

Experimental Workflow for Soft Bioelectronics

The comparative analysis presented in this guide underscores that organic semiconductors, hydrogels, and conductive polymers each occupy a unique and complementary niche in the soft bioelectronics landscape. The future of the field lies not in the supremacy of a single material, but in the strategic integration of these materials into hybrid systems that leverage their collective strengths. Examples include hydrogel-semiconductor composites for high-sensitivity biosensing and conductive polymer-laden hydrogels for injectable, multifunctional neural interfaces [22] [23].

Future advancements will be driven by several key trends: the development of high-performance, environmentally stable organic semiconductors; the refinement of AI-driven design and 4D-bioprinting techniques for fabricating intelligent hydrogel scaffolds [28]; and the ongoing pursuit of enhanced biocompatibility and long-term stability in conductive polymers [25]. As these material innovations converge, they will continue to blur the lines between electronics and biology, enabling a new era of diagnostic and therapeutic devices that are seamlessly and symbiotically integrated with the human body.

The evolution of bioelectronics from rigid to soft constructs represents a paradigm shift in medical device technology. Traditional rigid implants, composed of materials like silicon and metals with a Young's modulus exceeding 1 GPa, exhibit significant mechanical mismatch with biological tissues (typically in the kPa range), leading to inflammation, fibrosis, and eventual device failure [1] [2]. This mechanical mismatch hinders conformal contact, causing poor signal quality and tissue damage during movement [29] [30]. Soft bioelectronics address these limitations through innovative structural designs that enable flexibility and stretchability while maintaining high electronic performance. Among these strategies, three principal architectural approaches have emerged: ultra-thin films, mesh geometries, and serpentine structures. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these designs, focusing on their mechanical resilience, electrical stability, and performance in biomedical applications, to inform researchers and development professionals in their selection of appropriate interface technologies.

Structural Design Fundamentals and Comparative Performance

Ultra-Thin Films

Design Principle: Ultra-thin films reduce bending stiffness by minimizing device thickness to the micrometer or sub-micrometer scale, enabling flexibility through minimal mechanical cross-section [31] [32]. This approach allows conventional rigid electronic materials to conform to curved biological surfaces.

Fabrication Methodology: Typically involves deposition and patterning of thin metal films (e.g., gold, platinum) or silicon membranes on flexible substrates like polyimide (PI) or parylene using photolithography and etching processes [29] [32]. Silicon-on-insulator (SOI) technologies facilitate the creation of hyperflexible silicon-based thin-film membranes with nanometer-scale structural dimensions [29].

Performance Characteristics: Devices with thicknesses below 100 µm achieve significantly reduced bending stiffness (< 10⁻⁹ Nm), enabling conformal contact with tissues [1]. However, a significant drawback is their compromised mechanical robustness and handling difficulty [31]. Thin films also have limited inherent stretchability and may suffer from fatigue failure under repetitive cyclic loading [32].

Mesh Geometries

Design Principle: Mesh geometries incorporate interconnected networks of conductive traces with strategically placed openings, distributing mechanical strain across the structure and enhancing both flexibility and permeability [29] [33]. These designs are categorized mainly as open-mesh and closed-mesh configurations.

Fabrication Methodology: Fabricated using laser cutting or photolithographic patterning of metal-coated polymer substrates (e.g., gold on polyimide) [33]. Advanced manufacturing techniques like 3D printing enable sophisticated mesh module designs [29].

Performance Characteristics: A comparative study evaluating gold-coated polyimide mesh electrodes under standardized bending and stretching tests revealed distinct performance differences between open-mesh and closed-mesh designs [33]. The table below summarizes quantitative findings from this controlled comparison, where all designs had consistent conductive area (50%), trace width (0.8 mm), and overall dimensions (11.21 mm × 11.21 mm).

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Mesh Electrode Geometries under Mechanical Strain

| Performance Metric | Open-Mesh Design | Closed-Mesh Design |

|---|---|---|

| Resistance Variation under Strain | Higher variation due to longer current paths and sparse material distribution [33] | Lower variation; more stable due to denser conductive network [33] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) in EMG | Lower SNR | Highest SNR (up to 14.83 dB) with minimal motion artifacts [33] |

| Handling Motion Artifacts | Better for handling motion artifacts due to high flexibility [33] | Balanced performance across various strains [33] |

| Stretchability | Maximizes stretchability and surface conformity [33] | Provides moderate stretchability with electrical stability [33] |

Serpentine Structures

Design Principle: Serpentine structures utilize wavy, horseshoe-like meandering traces to accommodate applied strain through in-plane bending, twisting, and out-of-plane buckling rather than material stretching [33] [32]. This design localizes deformation away from sensitive active components.

Fabrication Methodology: Achieved through photolithographic patterning of metal traces on elastomeric substrates (e.g., PDMS, Ecoflex) or as interconnects in island-bridge configurations [29] [32]. The island-bridge architecture utilizes rigid electrode islands connected by soft, stretchable serpentine bridges, effectively decoupling mechanical and electrical strain [33].

Performance Characteristics: Serpentine interconnects demonstrate exceptional ability to withstand substantial mechanical deformation. Research shows that vertical serpentine structures fabricated on silicon platforms can withstand up to 350% strain while maintaining electrical stability, with less than a 2% change in electrical resistance under 300% strain [32]. The island-bridge design incorporating serpentine interconnects shows the lowest resistance variation (±1.61%) under standardized testing [33]. However, limitations include space inefficiency due to the required meandering paths, which reduces functional density, and potential strain concentration at the bridge interfaces in island-bridge designs [33] [32].

Table 2: Comprehensive Comparison of Structural Flexibility Designs

| Design Characteristic | Ultra-Thin Films | Mesh Geometries | Serpentine Structures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Reduced bending stiffness via minimal thickness [31] | Strain distribution through porous network [33] | Strain accommodation through meandering traces [32] |

| Typical Materials | Thin metals, silicon membranes on polyimide [29] | Gold-coated polyimide, laser-cut polymers [33] | Gold, copper on elastomers; silicon with PI encapsulation [32] |

| Effective Strain Range | Limited inherent stretchability | Open-mesh: High; Closed-mesh: Moderate [33] | Very high (up to 350% demonstrated) [32] |

| Electrical Stability under Strain | Moderate | Closed-mesh: High stability; Open-mesh: Lower stability [33] | Very high (minimal resistance variation) [33] |

| Functional Density | High | Moderate (reduced by openings) | Low to moderate (space-inefficient) [32] |

| Fabrication Complexity | Moderate | Low to moderate | High (particularly for 3D architectures) [32] |

| Ideal Application Context | Flexible but minimally-stretched interfaces [31] | Conformal surfaces with moderate movement; EMG sensing [33] | High-stretch environments; Interconnects between rigid islands [33] |

Experimental Protocols for Performance Validation

Mechanical Reliability Testing

Cyclic Bending Test Protocol: Electrode samples are mounted on a motorized stage that induces repeated bending at a specified radius (e.g., 5mm bend radius). Resistance is continuously monitored throughout thousands of cycles (typically 10,000+ cycles) to assess mechanical fatigue resistance. Testing should be performed at frequencies simulating physiological movements (e.g., 1-2 Hz for joint motion) [33].

Uniaxial Stretching Test Methodology: Samples are clamped in a tensile testing system and subjected to controlled strain levels (e.g., 10-30%) while measuring electrical resistance in real-time. The strain is applied cyclically at physiological relevant rates. The parameter of interest is resistance variation, calculated as ΔR/R₀ = (R - R₀)/R₀, where R₀ is initial resistance and R is measured resistance under strain [33].

Electrophysiological Signal Acquisition

EMG Signal Quality Assessment: Electrodes are applied to skin surfaces over target muscles (e.g., biceps brachii). Participants perform standardized movements (e.g., hand grips) while signals are acquired via Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) circuits. Signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is calculated as SNR = 20log₁₀(Asignal/Anoise), where Asignal is the RMS amplitude of the EMG signal during contraction and Anoise is the RMS amplitude during rest [33].

Electrode-Skin Impedance Measurement: Using a three-electrode configuration with the test electrode as working electrode, a large surface area counter electrode, and a reference electrode. Impedance is measured across a frequency spectrum (e.g., 1-1000 Hz) relevant to biopotential recordings using an impedance analyzer [6].

Mechanism Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanisms through which each structural design accommodates mechanical strain while maintaining electrical functionality.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Materials for Fabricating Flexible Bioelectronic Structures

| Material/Reagent | Function in Research Context | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Polyimide (PI) Films | Flexible substrate material with high thermal stability and mechanical strength [33] | Base substrate for ultra-thin films and mesh electrodes [33] |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | Elastomeric substrate/encapsulation with high stretchability and biocompatibility [29] | Matrix for serpentine interconnects; temporary adhesive in fabrication [33] |