Optimizing Stimulation Waveforms for Selective Neuromodulation: From Biophysical Principles to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the strategies and challenges in optimizing electrical stimulation waveforms to achieve selective neural activation.

Optimizing Stimulation Waveforms for Selective Neuromodulation: From Biophysical Principles to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the strategies and challenges in optimizing electrical stimulation waveforms to achieve selective neural activation. Aimed at researchers and biomedical professionals, it synthesizes foundational biophysical principles, cutting-edge computational and experimental methodologies, and comparative analyses of emerging technologies. The content covers key aspects from overcoming the non-selective recruitment inherent in exogenous stimulation to the application of novel paradigms like temporal interference and orientation-selective stimulation. By integrating recent findings from spinal cord, peripheral nerve, and cortical stimulation studies, this review serves as a critical resource for developing next-generation, precision neuromodulation therapies for neurological disorders and restorative neurotechnology.

The Biophysical Foundation of Selective Activation: From Size Principles to Recruitment Order

Theoretical Foundations: Natural vs. Artificial Recruitment

What is Henneman's Size Principle?

Henneman's Size Principle describes the natural, orderly recruitment of motor units by the central nervous system. It states that motor units are recruited from smallest to largest based on the force requirement of a movement [1] [2].

- Orderly Recruitment: Low-force, fatigue-resistant slow-twitch (Type I) muscle fibers, innervated by smaller motor neurons, are recruited first. As force demands increase, higher-force, fatigable fast-twitch (Type II) fibers, innervated by larger motor neurons, are recruited [1].

- Physiological Benefits: This organization minimizes fatigue by using endurance fibers for low-intensity tasks and reserves high-force fibers for strenuous activities. It also ensures a smooth, linear increase in force output [1].

- Underlying Mechanism: Smaller motor neurons have a higher membrane resistance, meaning they require a lower synaptic current to reach their firing threshold and are therefore more easily excited than larger neurons [1].

How does exogenous electrical stimulation alter this natural order?

Conventional electrical stimulation (ES) often reverses or disrupts this natural recruitment hierarchy, a phenomenon critical for researchers to understand when designing experiments.

- Reversal of Recruitment: Unlike the natural system, exogenous stimulation with typical rectangular pulses tends to activate larger, fast-twitch motor units first. This occurs because the larger axons associated with these units have a lower resistance to the applied electric current [1].

- Spatially Fixed and Temporally Synchronous Activation: Some research suggests that ES creates a non-selective pattern where recruitment is not orderly but instead is both "spatially fixed and temporally synchronous" [1]. This is fundamentally different from the finely graded, asynchronous natural activation.

- Consequence for Fatigue: Recruiting the highly fatigable fibers first can lead to rapid muscle exhaustion, which is a significant limitation in therapeutic and functional electrical stimulation applications [1].

Table: Key Differences Between Natural and Electrically Induced Recruitment

| Feature | Natural Recruitment (Size Principle) | Conventional Exogenous Stimulation |

|---|---|---|

| Recruitment Order | Small → Large Motor Units | Large → Small Motor Units |

| Initial Fiber Type Activated | Slow-Twitch (Fatigue-Resistant) | Fast-Twitch (Fatigable) |

| Activation Pattern | Orderly, Asynchronous | Non-selective, Synchronous |

| Fatigue Onset | Delayed | Rapid |

| Control Mechanism | Neurological (Synaptic Input) | Electrical (Axon Properties) |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: Why does my electrical stimulation protocol cause rapid muscle fatigue in subjects?

Answer: The most likely cause is the reversal of Henneman's Size Principle. Your stimulation parameters are probably recruiting large, fast-twitch, highly fatigable motor units before the smaller, fatigue-resistant ones [1]. This depletes energy reserves rapidly. To mitigate this, explore waveform shapes that promote more selective or natural-order recruitment.

FAQ 2: How can I improve the selectivity of my stimulation to target specific neural elements?

Answer: Achieving selectivity is a core challenge. Consider these factors, which can be optimized using computational models [3]:

- Stimulation Waveform Shape: Moving beyond simple rectangular pulses is key. Asymmetric biphasic pulses or waveforms with sub-threshold pre-pulses can help differentiate between cell bodies and passing axons or between fiber diameters [3].

- Stimulation Frequency: Evidence suggests that sinusoidal stimulation at specific frequencies can preferentially activate different cell types (e.g., photoreceptors at 5 Hz, bipolar cells at 25 Hz, ganglion cells at 100 Hz) [4]. This frequency-dependent selectivity may be applicable in other neural tissues.

- Pulse Duration: Shorter duration pulses generally improve spatial selectivity (activating fibers close to the electrode) and fiber diameter selectivity [3].

FAQ 3: My experimental results with electrical stimulation are inconsistent. What could be the source of error?

Answer: Inconsistencies often stem from technical setup rather than the biological preparation.

- Incomplete Circuit: The most common problem is a loss of contact between electrodes, leads, and the skin. If your stimulator cuts out at low intensities (e.g., 5-6 mA), it is often a safety alert for a broken circuit. Check for damaged leads, faulty electrodes, or poor electrode-skin contact [5].

- Stimulator Artifacts: Large stimulation artifacts can obscure neural recordings. Using charge-balanced waveforms and ensuring proper grounding can help reduce these artifacts.

Experimental Protocols for Selective Activation Research

Protocol: Investigating Frequency-Dependent Selective Activation

This protocol is adapted from studies on retinal stimulation, demonstrating a method to achieve selective neural targeting [4].

Objective: To determine the optimal sinusoidal frequency for selectively activating different neuronal populations in an in vitro preparation.

Materials:

- In vitro neural tissue preparation (e.g., retinal explant, nerve bundle).

- Microelectrode for localized sinusoidal stimulation (e.g., Pt-Ir electrode, ~10 kΩ).

- Cell-attached or whole-cell patch-clamp rig for recording from individual neurons.

- Pharmacological blockers (e.g., CNQX for AMPA/Kainate receptors, CdCl₂ for synaptic transmission blockade).

- A sinusoidal waveform generator.

Method:

- Setup: Mount the tissue in a recording chamber and continuously perfuse with oxygenated physiological solution at a controlled temperature (e.g., 36°C).

- Stimulation: Position the stimulating electrode ~25 μm above the target tissue. For a focused investigation, compare electrode placement over the soma region versus over the distal axon.

- Stimulation Parameters: Apply a series of sinusoidal waveforms at different frequencies (e.g., 5 Hz, 25 Hz, 100 Hz) with a fixed duration and pressure/current.

- Recording: Simultaneously record neural responses (spiking or subthreshold potentials) from target cells.

- Pharmacology: To elucidate direct versus synaptically mediated responses, repeat the stimulation in the presence of synaptic blockers.

- Analysis: Calculate the spike probability or peak postsynaptic current for each frequency. Plot the response magnitude against stimulation frequency to identify the optimal frequency for a given cell type.

Protocol: Model-Based Optimization of Stimulation Waveforms

This protocol uses computational modeling to design and test efficient and selective stimulation waveforms, drastically reducing experimental trial-and-error [6] [3].

Objective: To use a surrogate neural fiber model to design a stimulation waveform that selectively activates target fibers within a mixed nerve.

Materials:

- High-performance computer with GPU.

- Publicly available finite element model of the target nerve and electrode.

- Computational environment like NEURON or a machine learning-based surrogate model (e.g., AxonML/S-MF) [6].

- Electrophysiology setup for in vivo or in vitro validation.

Method:

- Model Construction: Implement a realistic model of the target nerve, including the electrode geometry and the spatial distribution of different fiber types (e.g., using the MRG model for myelinated fibers) [6].

- Define Optimization Goal: Formally state the objective, such as "maximize activation of 10 μm fibers while minimizing activation of 12 μm fibers."

- Parameter Sweep & Training: Use the model to generate a dataset of fiber responses to a wide range of waveform parameters (amplitude, pulse width, shape). Train the surrogate model on this dataset [6].

- Waveform Optimization: Run a gradient-based or gradient-free optimization algorithm on the surrogate model to find the waveform parameters that best meet the defined goal.

- Validation: Test the computationally optimized waveform in a biological preparation and compare the observed selectivity with the model's predictions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Reagents and Materials for Selective Activation Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| McIntyre-Richardson-Grill (MRG) Model | A validated, non-linear computational model of mammalian myelinated nerve fibers. The gold standard for predicting responses to electrical stimulation [6]. | Used to simulate AP propagation and predict activation thresholds for different waveform parameters [6]. |

| Surrogate Myelinated Fiber (S-MF) Model | A GPU-accelerated, machine-learning-based version of the MRG model. Enables rapid, high-throughput prediction of fiber responses for large-scale parameter optimization [6]. | Offers a >10,000x speedup over conventional models, making complex optimization feasible [6]. |

| TRPA1 Channel Constructs | A sonogenetic tool (e.g., hsTRPA1). When expressed in specific cells, it renders them sensitive to ultrasound stimulation, offering an alternative non-invasive control method [7]. | Allows selective activation of transfected neurons with ultrasound at frequencies like 7 MHz, which can be focused on small brain volumes [7]. |

| Sinusoidal Waveform Generator | Delivering frequency-specific stimulation to probe or exploit the frequency-dependent excitability of different neural targets [4]. | Critical for experiments investigating frequency-based selective activation [4]. |

| Synaptic Blockers | Pharmacological agents used to isolate direct neuronal stimulation from indirect, synaptically mediated responses [4]. | Examples: CNQX (AMPA receptor blocker), CdCl₂ (calcium channel blocker). |

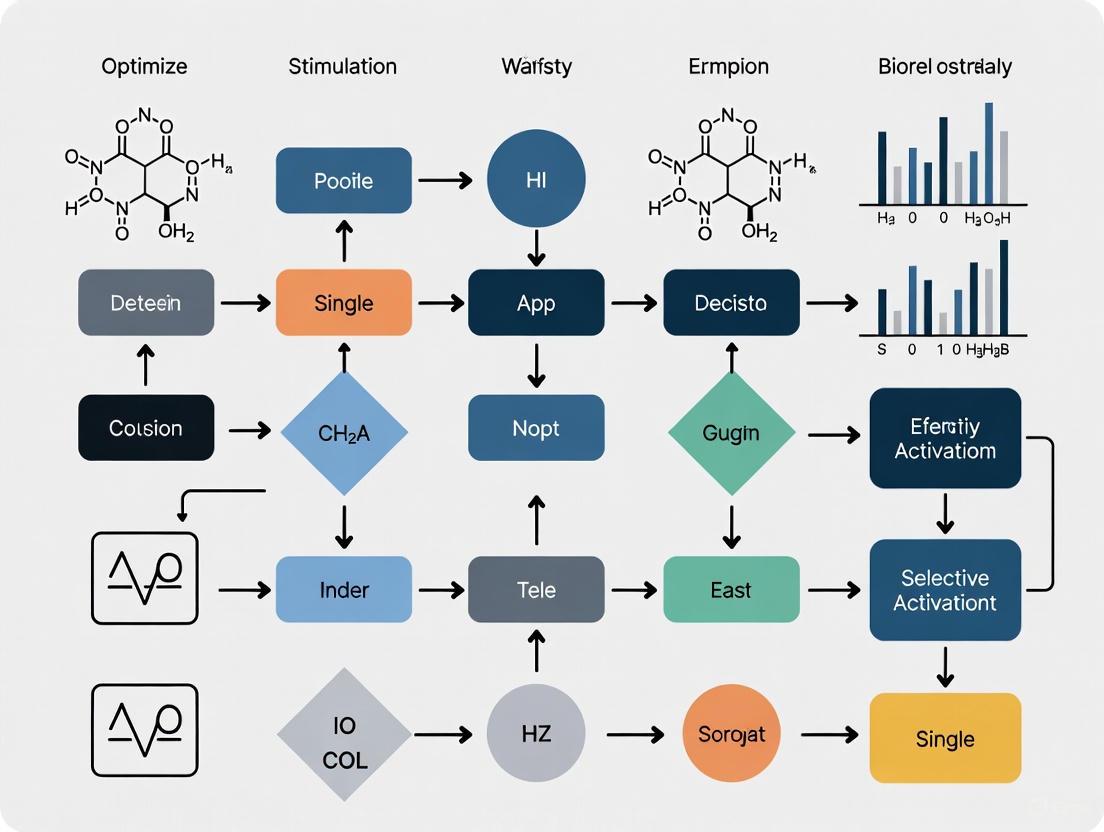

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Natural vs. Electrical Recruitment Order

Workflow for Selective Waveform Optimization

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Why does my model show significant errors in activation threshold when I use short-duration pulses? Traditional computational models like the Peterson surrogate can overestimate thresholds by more than 150% at short pulse widths because they do not fully capture the non-linear dynamics of ion channels, particularly the transition from sodium to potassium channel dominance at very short durations (below ~4 μs). For accurate results, use a modern surrogate model like S-MF (Surrogate Myelinated Fiber), which demonstrates a mean absolute percentage error of less than 2.5% across a wide range of pulse widths and fiber diameters by leveraging GPU acceleration and machine learning-trained biophysical properties [6] [8].

2. How can I improve the energy efficiency and selectivity of my stimulation waveforms? Conventional symmetric or monophasic pulses often trade off selectivity for high energy consumption. Employ an unconstrained optimization framework (like Particle Swarm Optimization) to design novel, asymmetric waveforms. This approach has yielded pulses with near-rectangular main phases that reduce energy loss by up to 92% compared to conventional monophasic pulses while maintaining or even improving directional selectivity, as evidenced by significant motor-evoked potential latency differences [9] [10].

3. My experimental strength-duration curve doesn't match the classical Lapicque or Weiss model. Is this normal? Yes, this is expected. The classical strength-duration models were derived for intracellular stimulation. For extracellular stimulation, the relationship is different due to the complex spatial interaction of the electric field with the axon and the distinct roles of different ion channels. The curve for extracellular stimulation typically has a slope of approximately -0.72 in log-log coordinates for pulse durations between 4 μs and 5 ms (dominated by sodium channels), which is less steep than the classical -1 slope [8].

4. What factors could be causing unexpected conduction delays in my unmyelinated axon model? Beyond standard cable properties, the presence of intracellular organelles like mitochondria can significantly impact conduction velocity. Mitochondria occupy axonal volume, increasing axial resistance. In small unmyelinated axons (e.g., ~0.4 μm diameter), a mitochondrial cross-sectional occupancy of about 26% can induce measurable delays. Ensure your computational model accounts for internal obstructions, as standard cables are often modeled as organelle-free [11].

5. How does the "strength-frequency" relationship differ from the "strength-duration" relationship? The strength-duration curve describes how the threshold current for a single pulse depends on that pulse's duration. The strength-frequency curve, relevant for repetitive stimulation like micromagnetic neurostimulation, describes how the threshold current for eliciting a response (e.g., an EPSP) changes with the frequency of the applied pulses. Generally, increasing the stimulation frequency leads to a decrease in the current amplitude threshold required for activation [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Activation Thresholds Across Replicates

- Potential Cause 1: Unaccounted for biophysical variability in axonal properties.

- Solution: Standardize the state of intrinsic neural activity before testing. Axonal excitability is dynamically regulated by factors like resting membrane potential, which can inactivate potassium channels (e.g., Kv1.2, Kv1.4) and alter the action potential waveform [13].

- Potential Cause 2: Minor shifts in electrode position or orientation.

- Solution: For magnetic stimulation, carefully control the coil orientation. The effectiveness of micromagnetic neurostimulation (μMS) is highly dependent on the orientation of the μcoil relative to the neural fibers. Use a customized, easy-to-adjust holder like the "MagPen" for reproducible placement [12].

Problem: Low Spatial Selectivity During Targeted Stimulation

- Potential Cause: The stimulation waveform is not optimized for the specific neural target within the electric field.

- Solution: Implement a computational optimization workflow.

- Model: Use a multi-scale neuron model embedded in a realistic electric field distribution (e.g., from SimNIBS) [9].

- Define Objective: Establish a selectivity index, such as the ratio of activation thresholds in your target region versus the entire stimulated area [9].

- Optimize: Use a gradient-based or gradient-free (e.g., Particle Swarm) optimization algorithm to find waveform parameters that minimize this index. This can significantly improve focality from the temporal domain, even with a fixed electrode [6] [9].

- Solution: Implement a computational optimization workflow.

Problem: Excessive Coil Heating During Repetitive Stimulation Protocols

- Potential Cause: The stimulation waveform is energy-inefficient.

- Solution: Move beyond traditional biphasic or monophasic pulses. Optimize for energy loss (Joule heating) directly within your waveform design framework. As demonstrated with TMS, optimized asymmetric pulses can reduce the energy loss in the coil by up to 92%, enabling rapid-rate protocols without overheating [10].

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: Key Parameters from Strength-Duration Research

| Parameter | Description | Typical Value / Range | Context / Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rheobase | Minimum current for activation at a theoretically infinite pulse duration [14]. | 2-18 mA (clinical settings) [14]. | Clinical neurophysiology. |

| Chronaxie | Pulse duration at which the activation threshold is twice the rheobase [14]. | < 1 ms (normal muscle) [14]. | Clinical neurophysiology. |

| Short-Pulse Slope (log-log) | Slope of the strength-duration curve for extracellular stimulation with short pulses [8]. | -0.72 (for durations ~4μs-5ms) [8]. | Hodgkin-Huxley model, sodium-channel dominated. |

| S-MF Threshold Error | Mean absolute percentage error of the S-MF model vs. the NEURON MRG model [6]. | < 2.5% (across various diameters) [6]. | Machine learning surrogate model. |

| S-MF Speedup | Computational speed increase of the S-MF model over NEURON [6]. | 80x (single GPU vs. 375 CPU cores) [6]. | High-performance computing. |

Table 2: Outcomes of Waveform Optimization for Selective Stimulation

| Optimization Method | Key Achievement | Performance Outcome | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient-Based/Free with S-MF | Selective activation in vagus nerve models [6]. | High accuracy in predicting thresholds (R² = 0.999) [6]. | Peripheral nerve stimulation (e.g., VNS). |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | Improved TMS stimulation selectivity (temporal domain) [9]. | Reduced selectivity index (f₁), indicating more focal activation [9]. | Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. |

| Unconstrained Asymmetric Pulse Optimization | Directional selectivity with high energy efficiency [10]. | 92% less energy loss vs. monophasic pulses; 1.79 ms MEP latency difference [10]. | Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining the Strength-Duration Curve Using a Computational Model

This protocol outlines how to generate a strength-duration curve using a modern, high-throughput surrogate axon model.

- Model Selection: Implement the Surrogate Myelinated Fiber (S-MF) model within the AxonML framework on a GPU-enabled system. This model accurately replicates the gold-standard MRG fiber model with a significant speedup [6].

- Setup Configuration:

- Fiber Properties: Define the diameter (e.g., 6-14 µm for myelinated fibers) and place it within a computational nerve morphology (e.g., human or pig vagus nerve model) [6].

- Electrode Configuration: Select an electrode type (e.g., cuff with monopolar or bipolar stimulation) and position it relative to the fiber [6].

- Stimulation Waveform: Define a set of rectangular monophasic pulses with durations spanning the range of interest (e.g., from microseconds to milliseconds) [6] [8].

- Threshold Determination: For each pulse duration, run a binary search algorithm to determine the minimum current amplitude (threshold) required to elicit a propagating action potential. The search should continue until the threshold is determined with a desired precision (e.g., 1%) [6].

- Data Analysis: Plot the threshold current (I) against the pulse duration (τ). Fit the data to analyze its slope in log-log space and compare it to classical (Lapicque) and modern (non-linear) expectations [8].

Protocol 2: Optimizing a Stimulation Waveform for Selectivity Using PSO

This protocol describes using an intelligent algorithm to find a waveform that selectively activates a target neuronal population.

- Define the Field: Use finite-element method (FEM) software (e.g., SimNIBS) to calculate the electric field distribution generated by your stimulator in a realistic tissue model (e.g., from an MRI) [9].

- Parameterize the Waveform: Represent the stimulation waveform as a series of levels. For a four-level TMS pulse, the parameters are the voltage (V₁-V₄) and pulse width (pw₁-pw₄) for each level, constrained by the circuit's capacitor voltages and total pulse width [9].

- Formulate the Optimization Problem:

- Decision Variables: The waveform parameters (e.g., V₁, V₂, pw₁, pw₂).

- Objective Function: A selectivity index (e.g.,

f₁ = Σ(threshEs_ROI) / Σ(threshEs_all)), where a smallerf₁indicates better selectivity. The goal is to minimizef₁[9]. - Constraints: Include practical limits like total pulse width and zero net current [9].

- Run Optimization: Employ a Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm. The algorithm will iteratively propose new waveform parameters, simulate the neuronal response using a multi-scale neuron model, and calculate the selectivity index until a minimum is found [9].

- Validation: Test the optimized waveform in your experimental setup and measure outcomes like motor threshold and activation latency, comparing them to conventional waveforms [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function in Research | Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| AxonML/S-MF Model | High-throughput prediction of axonal responses to electrical stimulation [6]. | A GPU-based machine learning surrogate model that dramatically accelerates simulations of neural fibers while retaining high accuracy [6]. |

| Multi-scale Neuron Model | Realistic simulation of neuron populations in a defined electric field [9]. | Integrates neuron morphology and coordinates from databases (e.g., NEURON) with electric field distributions from FEM software to predict stimulation thresholds [9]. |

| Tetrodotoxin (TTX) | Sodium channel blocker used for validation [12]. | Applying TTX blocks action potential-dependent synaptic responses. Recovery after washout confirms that recorded EPSPs are due to direct neural stimulation [12]. |

| MagPen (μCoil) | A prototype for precise micromagnetic stimulation (μMS) [12]. | A biocompatible, orientable microcoil that allows for controlled delivery of magnetic stimuli to brain slices, enabling the study of strength-frequency relationships [12]. |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) Algorithm | An intelligent algorithm for waveform parameter search [9]. | Efficiently navigates the high-dimensional parameter space of possible waveforms to find those that optimize a desired objective, such as selectivity or energy efficiency [9]. |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Diagram 1: Strength-Duration Relationship Determination Workflow

Diagram Title: Strength-Duration Curve Workflow

Diagram 2: Key Ion Channels Modulating Dopaminergic Axon Excitability

Diagram Title: Axonal Excitability Modulation Pathways

The Challenge of Preferential Large-Fiber Activation and Strategies for Targeting Small Diameter Fibers

Technical Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Unintended Large-Fiber Activation

Problem: During experiments designed to activate small-diameter fibers (e.g., C-fibers, Aδ-fibers), you observe physiological responses indicative of concurrent large-fiber (Aα/Aβ) activation, such as muscle twitches or laryngeal EMG signals in vagus nerve studies [15].

Solutions:

- Check Electrode Configuration: Verify you are using a pin electrode setup rather than patch electrodes. Pin electrodes deliver high current density in upper skin layers and are more suitable for small-fiber activation [16].

- Adjust Pulse Duration: Increase the duration of exponential pulses to 100 ms. This leverages the accommodation properties of large fibers, which become less responsive to longer duration pulses compared to small fibers [16].

- Optimize Pulse Shape: Switch from rectangular to exponentially rising pulse shapes. Rectangular pulses preferentially activate large fibers, while slowly rising exponential pulses can elevate large-fiber activation thresholds [16].

- Modulate Stimulation Intensity: Ensure stimulation intensity is appropriately calibrated (e.g., 10 times perception threshold for maximal pain ratings in human subjects) rather than using supramaximal stimulation [16].

Guide 2: Overcoming Limited Selectivity in Vagus Nerve Stimulation

Problem: Vagus nerve stimulation elicits unwanted side effects (e.g., coughing, hoarseness, bradycardia) due to co-activation of large fibers innervating the larynx and pharynx [15].

Solutions:

- Implement Current Steering: Use multi-contact cuff electrodes and interferential current stimulation (i2CS) to create spatially focused activation fields. Adjust steering ratio to target organ-specific fascicles [17].

- Apply Anodal Block: Utilize anodic stimulation to preferentially activate orthogonal fibers approaching or leaving the electrode, which can target different fiber populations than cathodic stimulation [18].

- Utilize Kilohertz-Frequency Signals: Employ high-frequency signals (e.g., ~20 kHz) in interferential paradigms to achieve more selective activation of smaller vagal fibers [17] [15].

- Optimize Electrode Design: Ensure electrode arrays maintain proper insulation to prevent current leakage that can activate nearby large-diameter fibers with low activation thresholds [15].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does conventional electrical stimulation preferentially activate large-diameter fibers instead of small-diameter fibers?

A1: This occurs due to fundamental biophysical principles. Large-diameter fibers have lower activation thresholds to exogenous electrical stimuli compared to small-diameter fibers. This creates an inverse recruitment order opposite to physiological activation (Henneman's size principle), where smaller fibers are naturally recruited before larger ones in biological systems [19]. The relationship between fiber diameter and activation threshold is well-established in computational models and experimental studies [6] [19].

Q2: What specific pulse parameters can enhance selective small-fiber activation?

A2: Research indicates several key parameters [16]:

- Pulse Shape: Exponentially rising pulses are superior to rectangular pulses

- Pulse Duration: Longer durations (≥15-100 ms) favor small-fiber activation

- Electrode Type: Pin electrodes paired with exponential pulses

- Stimulation Pattern: Single pulses may be more selective than trains for certain applications

Q3: How can I validate whether my stimulation protocol is successfully targeting small fibers?

A3: Employ these validation approaches:

- Physiological Markers: Monitor organ-specific responses known to be mediated by small fibers (e.g., bronchopulmonary responses in vagus nerve studies) [17]

- Computational Modeling: Use surrogate fiber models (e.g., S-MF) to predict activation thresholds across fiber diameters [6]

- Electrophysiological Recording: Measure evoked compound action potentials (eCAPs) to distinguish fast-fiber (large) versus slow-fiber (small) responses [17]

Q4: What are the most promising emerging technologies for selective fiber activation?

A4: Current advanced approaches include [6] [17]:

- Interferential Current Stimulation (i2CS): Uses temporal interference of high-frequency signals to create focused amplitude modulations

- Machine Learning-Optimized Stimulation: Leverages GPU-accelerated surrogate models to design selective stimulation parameters

- Anodal Block Techniques: Exploits orientation-dependent activation of fibers

- Multi-Contact Cuff Electrodes: Enables spatial targeting of specific fascicles

Table 1: Stimulation Parameters for Selective Fiber Activation

| Parameter | Large-Fiber Preference | Small-Fiber Preference | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pulse Shape | Rectangular | Exponential rising | Exponential pulses with 100-ms duration show maximal large-fiber accommodation [16] |

| Pulse Duration | Short (≤2 ms) | Long (≥15-100 ms) | Perception thresholds for exponential pulses increase with durations ≥15 ms, indicating large-fiber accommodation [16] |

| Electrode Type | Patch | Pin | Pin electrodes deliver high current density in upper skin layers [16] |

| Stimulation Frequency | Low frequency (≤100 Hz) | Kilohertz-frequency (∼20 kHz) | Kilohertz signals in i2CS reduce large-fiber activation at interference focus [17] |

| Polarity | Cathodic | Anodic | Anodic stimulation preferentially activates orthogonal fibers at lower thresholds [18] |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Computational Models for Stimulation Optimization

| Model Type | Computational Speed | Accuracy | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEURON MRG Model | Baseline (reference) | High (gold standard) | Detailed biophysical studies, validation [6] |

| S-MF Surrogate | 2,000-130,000× faster than NEURON | R² = 0.999 for thresholds | Large-scale parameter sweeps, real-time optimization [6] |

| Peterson Surrogate | Faster than NEURON | MAPE = 31% (overestimates thresholds) | Basic threshold estimation [6] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Preferential Small-Fiber Activation Using Exponential Currents

Based on: [16]

Objective: To establish a methodology for preferential small-fiber activation using exponentially rising electrical currents.

Materials:

- Pin electrodes and patch electrodes

- Constant current stimulator capable of generating exponential and rectangular pulses

- Perception threshold measurement system

- Pain rating scale (for human subjects)

Methodology:

- Electrode Placement: Apply both pin and patch electrodes to the target area.

- Threshold Determination: Compare perception thresholds between electrode types using single 1-100 ms exponential and rectangular pulses.

- Stimulus-Response Evaluation: Deliver pulse trains at 10 Hz using intensities from 0.1 to 20 times perception threshold.

- Data Collection: Record perception thresholds and pain ratings for both single pulses and pulse trains.

- Parameter Optimization: Apply 100-ms exponential pulses at 10 times perception threshold for maximal small-fiber activation.

Validation: Successful implementation is indicated by increased perception thresholds with longer exponential pulse durations (≥15 ms), demonstrating large-fiber accommodation.

Protocol 2: Selective Vagus Nerve Stimulation Using Interferential Currents

Based on: [17]

Objective: To achieve organ-specific fiber activation in the vagus nerve using intermittent interferential current stimulation (i2CS).

Materials:

- Multi-contact epineural cuff electrode

- Dual-channel current source capable of high-frequency (∼20 kHz) stimulation

- Recording equipment for eCAPs and physiological responses (EMG, breathing)

- Computational model for prediction (optional)

Methodology:

- Electrode Configuration: Place multi-contact cuff around cervical vagus nerve.

- Stimulation Paradigm: Deliver i2CS through contact pairs with slightly different high frequencies to create amplitude modulations.

- Current Steering: Apply uneven stimulus intensities (steering ratios from -1 to +1) to shift activation focus.

- Response Monitoring: Record eCAPs, laryngeal EMG, and breathing responses.

- Selectivity Assessment: Compare responses to equivalent non-interferential sinusoidal stimulation.

Validation: Successful selective activation is confirmed when i2CS produces distinct organ responses (e.g., bronchopulmonary vs. laryngeal) that differ from non-interferential stimulation.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Pathways for Selective Small-Fiber Activation

Diagram 2: Experimental Optimization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Selective Activation Research

| Item | Function/Purpose | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Pin Electrodes | Deliver high current density to superficial skin layers; enhance small-fiber activation when paired with exponential pulses [16] | Cutaneous small-fiber studies, pain research |

| Multi-Contact Cuff Electrodes | Enable spatial selectivity through current steering and interferential stimulation patterns [17] | Vagus nerve studies, peripheral nerve stimulation |

| Exponential Pulse Generators | Generate slowly rising pulses that exploit accommodation properties of large-diameter fibers [16] | Preferential small-fiber activation protocols |

| Computational Models (S-MF) | GPU-accelerated surrogate models for rapid prediction of fiber responses to stimulation parameters [6] | Stimulation protocol optimization, parameter sweeps |

| High-Frequency Stimulators | Deliver kilohertz-range signals for interferential and blocking paradigms [17] | i2CS protocols, selective fiber activation |

| NEURON Simulation Environment | Gold-standard platform for modeling extracellular stimulation effects on detailed fiber models [6] [18] | Biophysical mechanism studies, model validation |

Neural Membrane Dynamics and Rectification Effects in Response to kHz Waveforms

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my kHz-frequency stimulation fail to produce the expected selective activation of small fibers? This is often due to incorrect parameter combination. Selective activation of small, unmyelinated C-fibers over larger A- and B-fibers requires a specific window of frequency and intensity. For rats, use frequencies >5 kHz at intensities of 7–10 times the activation threshold (T); for mice, use 15–25 × T. Outside this window, you may get simultaneous activation of all fiber types or complete conduction block [20] [21].

Q2: My sinusoidal stimulation is causing synchronous neural firing instead of the desired desynchronization. What is wrong? The desynchronization effect of sinusoidal waveforms is highly frequency-dependent. Lower frequencies (e.g., 50-100 Hz) produce higher desynchronization across the neural population, while higher frequencies (e.g., 500-1000 Hz) can lead to more regular, synchronous firing. Ensure you are using the appropriate frequency for your application. Furthermore, consider using a Fast Amplitude Modulated Sinusoidal (FAMS) waveform, which is specifically designed to combine the benefits of low and high-frequency effects to enhance desynchronization [22].

Q3: When trying to achieve nerve conduction block, which waveform shape is most efficient? Square waveforms generally have the lowest block threshold amplitude, meaning they require less current to initiate a block. However, when efficiency is measured in charge per cycle, triangular waveforms can require the least charge. For a balance of efficacy and efficiency, both sinusoidal and square waveforms at frequencies of 20 kHz or higher are considered optimal [23].

Q4: Do the high-frequency carriers in amplitude-modulated signals (like TAMS) directly activate nerves? For carrier frequencies greater than 20 kHz, the nerve activation threshold is determined almost exclusively by the signal's offset (the low-frequency envelope), not the carrier itself. The carrier component does not offer an activation advantage over conventional rectangular pulses, which simplifies waveform design for transcutaneous stimulation [24].

Troubleshooting Guide

Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

Table 1: Troubleshooting Neural Responses to kHz Waveforms

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unnatural or paresthetic sensations in sensory applications [22] | Highly synchronous neural activation from rectangular pulses. | Switch to a desynchronizing waveform like a low-frequency sinusoid or FAMS [22]. |

| Inability to selectively activate C-fibers [21] | Incorrect intensity or frequency parameters. | Calibrate intensity to the specific threshold (T) for your animal model (7-10x T for rats) and use frequencies >5 kHz [21]. |

| Rapid muscle fatigue during functional stimulation [22] | Synchronous firing patterns from constant-frequency pulse trains. | Implement biomimetic, variable-frequency pulse trains or kHz-frequency amplitude-modulated waveforms to desynchronize activity [22]. |

| High block threshold or excessive power consumption [23] | Suboptimal waveform shape or electrode material. | Use square waveforms for lower block thresholds or switch to high-charge-capacity electrodes like carbon black coatings [23]. |

| Poor translation of transcutaneous stimulation depth [24] | Assumption that kHz carrier directly activates deeper nerves. | Focus on optimizing the amplitude of the low-frequency envelope; carriers >20 kHz do not directly affect activation threshold [24]. |

Optimizing Waveform Parameters

Table 2: Key Parameters for Selective Activation and Conduction Block

| Objective | Recommended Waveform | Frequency Range | Key Intensity Parameter | Model System Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selective C-fiber Activation [21] | Biphasic square pulse | >5 kHz | 7-10 x T (Rat); 15-25 x T (Mouse) | Rat & Mouse Vagus Nerve |

| Neural Firing Desynchronization [22] | Low-frequency sinusoid or FAMS | 50-100 Hz (Sinusoid) | 1.5 x Threshold (T) | Feline Peripheral Nerve |

| Nerve Conduction Block [23] | Square wave | 10-60 kHz | Lowest Block Threshold (Amplitude) | Rat Sciatic Nerve |

| Efficient Conduction Block [23] | Triangular wave | 10-60 kHz | Lowest Charge per Cycle | Rat Sciatic Nerve (Computational) |

| Cortical Activation (DBS) [25] | Biphasic square pulse | 1 kHz (pulse width 45 µs) | ~85 µA (current-controlled) | Awake Mouse Hippocampus/Cortex |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing Selective C-Fiber Activation with kHz Stimulation

This protocol is adapted from methods to achieve selective activation of small, unmyelinated vagal C-fibers, which constitute over 80% of vagus nerve fibers [21].

1. Animal Preparation and Surgical Setup:

- Animals: Use adult male Sprague Dawley rats (300–550 g) or C57BL/6 mice (25–30 g).

- Anesthesia: Induce and maintain anesthesia using isoflurane (e.g., 4% for induction, 1.5–2% for maintenance).

- Physiological Monitoring: Maintain body temperature at 36.5–37.5 °C with a heating pad. Monitor ECG and respiration throughout.

- Nerve Exposure: Isolate the cervical vagus nerve (right cVN in rats, left in mice) via a midline neck incision. Minimize nerve manipulation by isolating only the caudal and rostral ends, leaving the middle portion within the carotid bundle.

2. Electrode Placement and Setup:

- Electrodes: Use custom tripolar cuff electrodes made with a polyimide substrate and sputter-deposited iridium oxide contacts (impedance 0.5–1.5 kΩ at 1 kHz).

- Placement: Position a stimulating cuff electrode on the nerve. Place a separate recording cuff electrode 5–6 mm away from the stimulating electrode center.

- Insulation: Apply silicone elastomer around the cuffs to minimize current leakage.

3. Stimulation and Validation of Selective Activation:

- Stimulation Waveform: Deliver symmetric, biphasic square pulses in 10-second trains.

- Key Parameters:

- Frequency: Use >5 kHz.

- Intensity: Calibrate carefully. For rats, use 7–10 times the activation threshold (T); for mice, use 15–25 x T.

- Validation with Probing Pulses: To confirm selective C-fiber activation and concurrent A/B-fiber block, interweave the kHz train with single monophasic probing pulses (100 μs for A/B-fibers, 600 μs for C-fibers). Briefly interrupt the kHz train for 30 ms (5 ms before and 25 ms after each probing pulse) to record artifact-free compound action potentials (CAPs). The presence of C-fiber CAPs with suppressed A/B-fiber CAPs indicates successful selective activation [21].

Protocol 2: Implementing FAMS for Desynchronized Neural Activation

This protocol outlines the use of the Fast amplitude-modulated sinusoidal (FAMS) waveform to evoke asynchronous, quasi-stochastic neural activity, which is useful for producing more naturalistic sensory percepts [22].

1. Computational Modeling (Initial Validation):

- Environment: Use the NEURON simulation environment.

- Neural Population: Model a heterogeneous population of sensory axons (diameters 6–12 μm) within a 100 μm² space.

- Stimulation Electrode: Model as a pair of ideal point sources.

- Waveform Definition: The FAMS waveform consists of a kHz-frequency carrier sinusoid that is amplitude-modulated at a lower frequency.

- Analysis: Compare the response to FAMS against conventional rectangular pulses. Quantify desynchronization by generating Peri-Stimulus Time Histograms (PSTHs). FAMS should produce spike timings that span the entire cathodic phase, demonstrating higher variability than the tight synchronization seen with rectangular pulses.

2. In Vivo Implementation:

- Animal Model: Utilize a feline model of peripheral nerve stimulation.

- Stimulation: Apply the FAMS waveform via a nerve cuff electrode.

- Recording and Analysis: Record neural activity and confirm that FAMS-evoked activity is more asynchronous than activity evoked by rectangular pulses, while still being controllable via simple stimulation parameters [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Specification / Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Tripolar Cuff Electrodes [21] | Polyimide substrate, IrOx contacts; for selective stimulation/recording. | Selective vagus nerve stimulation in rodents. |

| Programmable Stimulator [21] | Constant-current, capable of generating kHz-frequency biphasic square pulses (e.g., STG4008). | Delivery of precise kHz waveform trains. |

| High-Capacitance Electrodes [23] | Carbon black-coated electrodes; reduce block threshold and onset responses. | Efficient kilohertz nerve conduction block. |

| NEURON Simulation Environment [22] [23] | Platform for biophysical computational modeling of axons (e.g., MRG model). | Predicting neural response to novel waveforms in silico. |

| RHS2000 Controller [21] | 32-channel stim/record system for high-fidelity neural recording. | Recording compound action potentials during kHz stimulation. |

Experimental Workflow & Signaling Pathways

Diagram 1: FAMS Stimulation Experimental Workflow

Diagram 2: Selective C-Fiber Activation Principle

Diagram 3: kHz Waveform Nerve Block Mechanism

Computational and Experimental Methods for Designing Selective Waveforms

Leveraging Finite Element Models for Predicting Electric Field Distribution and Neural Activation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common causes for a large discrepancy between my simulated electric fields and experimentally measured neural activation thresholds?

Discrepancies often arise from these key areas:

- Model Fidelity vs. Computational Cost: High-fidelity, microscopically detailed Finite Element Method (FEM) simulations are computationally intensive and can be prohibitive for large-scale parameter exploration [6] [26]. Simplifications in your model geometry may omit crucial details that affect field distribution.

- Neural Model Limitations: The accuracy of the neural activation prediction is limited by the biophysical neural model used. Simple threshold-based estimators can have errors exceeding 150%, while more complex non-linear models are computationally expensive [6].

- Biological Variability: The "electric field spatial noise" caused by microscopic physical cell structures can cause neuronal activation thresholds to vary by an average of around 10% from macroscopically homogeneous model predictions [27]. Individual anatomical differences also contribute to variability.

Q2: My model runs too slowly for parameter optimization. What strategies can I use to improve computational efficiency?

Leveraging machine learning-based surrogate models is a highly effective strategy. Researchers have achieved a 2,000 to 130,000x speedup over single-core NEURON simulations by using a GPU-based surrogate model (S-MF) of myelinated fibers. These surrogate models can generate full spatiotemporal responses to electrical stimulation orders-of-magnitude faster than conventional methods while retaining high predictive accuracy (e.g., R² = 0.999 for activation thresholds) [6]. Similarly, Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) can be trained on FEM data to directly predict electric potential distributions, bypassing the need for computationally intensive solvers in each iteration [26].

Q3: How can I enhance the selectivity of neural activation using waveform optimization?

Selective activation can be improved by moving beyond conventional constant-frequency pulses. Optimization algorithms like particle swarm optimization can be applied to parameterize stimulation waveforms. The key parameters to optimize include [28] [29]:

- Waveform Polarity: The ratio of the positive to negative integrated areas of the stimulation waveform.

- Temporal Pattern: The relative order and amplitude of induced electric field levels.

- Pulse Shape: Using arbitrary or irregular waveforms (e.g., sinusoidal, nested pulse, randomized).

Studies show that irregular stimulation patterns can induce neural activity states that more closely resemble natural, behaviorally relevant activity compared to the often "artificial" patterns driven by standard constant-frequency stimulation [29].

Q4: How do I validate that my computed electric fields are physically accurate?

A robust method is to derive a secondary physical quantity from your predicted field and compare it against experimental or high-fidelity simulation data. For instance, in a study using GCNs to predict electric potentials, the physical fidelity was validated by computing the capacitance matrices from the predicted fields and showing strong agreement with capacitances derived from traditional FEM fields [26]. This ensures the predicted fields are not just statistically accurate but also physically consistent.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: High Computational Demand in Large-Scale Models

Issue: Running FEM simulations for large nerve models or performing parameter sweeps is too slow.

| Solution | Description | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Implement Surrogate Models | Use machine learning models (e.g., GPU-based S-MF) trained on FEM data to approximate system responses [6]. | Massive speedup (several orders of magnitude) for simulation and optimization. |

| Use Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) | For electric field prediction, train a GCN on existing FEM solutions to directly output full-field distributions [26]. | Fast, one-step prediction of electric fields, enabling real-time applications. |

Workflow Diagram: Surrogate Model Implementation

Problem 2: Poor Selectivity of Neural Activation

Issue: The stimulation protocol activates non-targeted neural populations or fails to achieve specific recruitment.

Solution: Employ a closed-loop optimization framework that integrates FEM with neural response models.

- Parameterize Stimulation Waveform: Define your waveform by its amplitude, frequency, pulse width, and shape (e.g., rectangular, sinusoidal, arbitrary) [28] [29].

- Compute Electric Field: Use your FEM model to simulate the field distribution for a given set of waveform parameters.

- Predict Neural Activation: Apply the electric field to a surrogate neural model (e.g., S-MF) to predict the spatiotemporal neural response [6].

- Optimize for Selectivity: Use a gradient-based or gradient-free optimization algorithm (e.g., particle swarm) to iteratively adjust the waveform parameters. The objective function should maximize activation in target fibers and minimize activation in non-target fibers [6] [28].

Experimental Protocol: Selective Vagus Nerve Stimulation A referenced methodology for achieving selective stimulation is as follows [6]:

- Nerve Models: Use anatomically realistic FEM models of human and pig vagus nerves.

- Electrodes: Model different cuff geometries (e.g., ImThera 6-contact, LivaNova helical).

- Stimulation: Apply linear combinations of rectangular waveforms with randomized amplitudes, delays, and pulse widths.

- Neural Targets: Model myelinated fibers of various diameters (e.g., 6–14 µm) using a validated surrogate model (S-MF).

- Optimization: Implement both gradient-free and gradient-based optimization methods to find stimulation parameters that selectively activate specific fascicles.

Problem 3: Model Validation and Accuracy Concerns

Issue: Uncertainty about the real-world predictive accuracy of the coupled FEM and neural activation model.

Solution Strategy:

- Multi-Fidelity Validation: Compare your model's predictions against multiple data sources.

- Derived Quantity Analysis: As performed in electric capacitance tomography research, compute a secondary, physically relevant metric (like inter-electrode capacitance) from your model's output and validate it against experimental measurements [26].

- Benchmark Against Gold Standards: Compare your activation thresholds with those from established, high-fidelity simulation platforms like the MRG model in NEURON, which is considered a gold standard and has been experimentally validated [6].

Validation Workflow Diagram

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table: Key Computational Tools and Models for FEM-Neural Activation Research

| Item Name | Function & Application | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| S-MF (Surrogate Myelinated Fiber) Model | A GPU-based, high-throughput model for predicting neural fiber responses to electrical stimulation [6]. | Massively parallel; offers 2,000–130,000x speedup over CPU-based NEURON models while maintaining high accuracy (R²=0.999). |

| MRG (McIntyre-Richardson-Grill) Model | A gold-standard, biophysically detailed model of mammalian myelinated fibers, implemented in NEURON [6]. | Used for validating surrogate models; basis for many clinical translation studies and FDA-approved platforms. |

| Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) | Machine learning models for direct, one-step prediction of electric field distributions from sensor geometry and excitation patterns [26]. | Serves as a fast surrogate for FEM solvers; enables real-time field prediction and capacitance computation. |

| Particle Swarm Optimization | A gradient-free optimization algorithm for refining stimulation waveform parameters to maximize selectivity [28]. | Effective for exploring high-dimensional parameter spaces where gradient information is unavailable or costly. |

| NEURON Simulation Environment | The industry-standard platform for computationally demanding simulations of neurons, including extracellular stimulation [6]. | Currently the primary platform supporting complex fiber ultrastructure and extracellular voltage effects. |

Table 1. Performance Comparison of Neural Simulation Methods

| Model / Method | Computational Speed | Key Advantage | Key Limitation | Predictive Accuracy (vs. Experiment) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEM + NEURON (MRG) | Slow (Baseline) | High biophysical detail & validation [6] | Computationally prohibitive for optimization [6] | High (Gold Standard) [6] |

| FEM + S-MF Surrogate | 2,000 - 130,000x faster [6] | Enables large-scale parameter sweeps & optimization [6] | Requires training data from high-fidelity models [6] | Very High (R² = 0.999 for thresholds) [6] |

| Peterson Surrogate | Fast | Simplicity [6] | Limited waveform flexibility; overestimates thresholds (MAPE=31%) [6] | Moderate to Low [6] |

| GCN for E-Field | Fast (Real-time potential) | Bypasses iterative FEM solving [26] | Accuracy dependent on training data quality and scope [26] | High agreement in derived quantities (e.g., capacitance) [26] |

Table 2. Impact of Stimulation Waveform on Neural Activity

| Waveform Type | Effect on Oscillatory Power (e.g., Gamma) | Effect on High-Dimensional Activity State | Potential Clinical Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant-Frequency (Standard) | Effective entrainment [29] | Induces predominantly "artificial" patterns (dissimilar from behavior) [29] | Suitable for suppressing/enhancing a single biomarker [29] |

| Irregular Patterns (Sinusoidal, Nested Pulse, Randomized) | Similar entrainment to standard pulses [29] | Induces activity that more closely resembles natural, behavioral activity [29] | Beneficial for applications requiring complex, behaviorally-relevant state entrainment [29] |

| Optimized Arbitrary Waveforms | Information Not Available | Can achieve higher selectivity than monophasic waveforms [28] | Personalized therapy; enhanced selectivity for specific neural populations [28] |

Foundational Concepts and Definitions

What are the core components of an electrical stimulation waveform?

An electrical stimulation waveform is defined by several fundamental parameters, each controlling a specific aspect of the current delivered to the tissue. Understanding these components is essential for designing effective stimulation protocols [30].

- Amplitude: The magnitude or intensity of the current, measured in milliamps (mA) peak for neurostimulation. It directly influences the intensity of the evoked response.

- Phase Duration: The time elapsed from the beginning to the termination of a single phase of a pulse, measured in microseconds (µs). This parameter is critical for determining which neural elements are activated.

- Pulse Duration (Pulse Width): The total time from the beginning to the end of all phases within a single pulse, including any interphase interval.

- Interphase Interval: The short period of time between two successive phases of a single pulse when no electrical activity occurs. This interval can affect membrane capacitance and safety.

- Frequency (Pulse Rate): The number of pulses delivered per second, measured in Hertz (Hz). Frequency primarily modulates the temporal patterning of the neural response.

- Polarity: Refers to the direction of current flow. In monophasic pulses, current flows in one direction. In biphasic pulses, current flow alternates direction, typically featuring an active phase and a balancing phase to achieve net zero charge delivery, which minimizes the risk of skin irritation and tissue damage [30].

Parameter Effects and Quantitative Data

How do specific waveform parameters influence the amplitude and latency of evoked neural responses?

Systematic investigation, particularly in intracortical microstimulation (ICMS), has quantified how waveform parameters modulate motor-evoked potential (MEP) amplitude and onset latency. These relationships are foundational for engineering desired outcomes. The table below summarizes key findings from a study that varied parameters of a biphasic, cathode-leading waveform in the rat motor system [31].

Table 1: Effects of Stimulation Parameters on Motor-Evoked Potentials (MEPs)

| Parameter | Effect on MEP Amplitude | Effect on MEP Latency | Notable Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Amplitude | Continuous increase | No significant effect | A primary determinant of response strength. |

| Pulse Duration | Continuous increase | No significant effect | Longer durations deliver more charge per phase. |

| Stimulus Frequency | Increased up to a plateau (100-200 Hz) | Decreased with higher frequency | Higher frequencies facilitate temporal summation. |

| Train Duration | Increased up to a plateau (43-172 ms) | Decreased with longer trains | Longer trains provide more pulses to drive the response. |

| Interphase Interval | No significant effect in tested range | No significant effect in tested range | Tested from 10 µs to 640 µs; minimal influence. |

What are the clinical uses of different waveform types?

Different waveform shapes are suited to specific clinical and research applications based on their interaction with neural tissue. The selection is often a trade-off between efficacy, selectivity, and safety [30].

Table 2: Common Waveform Types and Their Clinical Applications

| Waveform Type | Clinical Uses |

|---|---|

| Monophasic (DC/Galvanic) | Iontophoresis, wound healing, denervated tissue stimulation. |

| Pulsed Galvanic | Edema reduction, wound healing, innervated muscle contraction. |

| Symmetrical Biphasic (AC) | Pain suppression (TENS), innervated muscle contraction (NMES). |

| Asymmetrical Biphasic (AC) | Pain suppression (TENS), innervated muscle contraction (NMES). Avoids net skin charge, reducing burn risk [30]. |

| Unbalanced Triphasic | Edema reduction, pain suppression. |

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Optimization

Protocol 1: Establishing a Motor Threshold and Response Curve using ICMS

This protocol is adapted from methods used to systematically map the effects of stimulation parameters on motor output [31].

- Animal Preparation: Anesthetize the rat (or other animal model) and secure it in a stereotaxic frame. Perform a craniotomy to expose the primary motor cortex.

- Electrode Implantation: Implant a microelectrode array or a single microelectrode into the forelimb region of the primary motor cortex.

- EMG Setup: Insert fine-wire electromyography (EMG) electrodes into the contralateral forelimb muscle of interest (e.g., a wrist or digit flexor).

- Stimulation and Recording:

- Set a baseline pulse waveform (e.g., cathodal-leading, biphasic pulse, 0.2 ms phase duration).

- Begin stimulation at a low current amplitude (e.g., 10 µA). Deliver short train stimuli (e.g., 13 pulses at 333 Hz).

- Simultaneously record the EMG for MEPs.

- If no MEP is observed, increase the current amplitude in small increments until a threshold response is identified.

- Parameter Variation: Once the threshold is found, systematically vary one parameter at a time (e.g., frequency from 50-400 Hz, train duration from 10-200 ms) while holding others constant. Record the amplitude and latency of the resulting MEPs for each parameter set.

- Data Analysis: Plot the MEP amplitude and latency against each parameter to generate input-output curves. Use this data to identify optimal parameters for a desired response profile.

Protocol 2: Optimizing Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) Waveforms for Selectivity

This protocol uses intelligent optimization algorithms to design TMS pulses for improved stimulation focus [9].

- Model Setup: Establish a multi-scale neuron model based on a real human head MRI. Use simulation software (e.g., SimNIBS) to obtain the electric field distribution of a TMS coil.

- Define Objective Function: Establish a selectivity index as the optimization target. For example, the ratio of the stimulation threshold in a target region of interest (ROI) to the threshold of all neurons in the stimulated field. A lower index indicates better selectivity [9].

- Parameterize Waveform: Define the TMS coil voltage waveform using a flexible parameter set. For a multi-level waveform, this includes the amplitude and pulse width for each voltage level [9].

- Run Optimization Algorithm: Implement a particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm. The algorithm will iteratively test different waveform parameter combinations in the model, seeking to minimize the selectivity index.

- Validation: Select the optimized waveforms from the algorithm and test them on the model. Compare the activation of the target region versus non-target regions against conventional waveforms (e.g., monophasic or biphasic pulses).

TMS Waveform Optimization Workflow

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ 1: Why is my stimulation failing to evoke a neural response despite high current amplitudes?

- Check Electrode Impedance: High impedance at the electrode-tissue interface can prevent current from reaching the target. For transcutaneous stimulation, the impedance of dry skin can be very high (e.g., ~25 kΩ for a 0.44 cm² electrode), requiring a stimulator with a high compliance voltage (e.g., ±150 V) to drive sufficient current [32]. Measure and ensure impedance is within an acceptable range.

- Verify Stimulator Specifications: Confirm your stimulator can deliver the required compliance voltage and current for your application (transcutaneous vs. invasive). Many benchtop stimulators designed for invasive use cannot output the high voltages needed to penetrate the skin [32].

- Review Pulse Parameters: The stimulus might be subthreshold. Ensure the pulse width is sufficiently long to depolarize the target neurons. Also, for motor evoked potentials, a train of pulses is often necessary; a single pulse may be insufficient [31].

- Confirm Target Location: Small errors in electrode placement over a nerve or cortical region can lead to complete failure of activation. Use anatomical landmarks, ultrasound, or stereotaxic coordinates to verify placement.

FAQ 2: How can I improve the spatial selectivity of my stimulation to avoid activating off-target areas?

- Optimize Waveform Polarity and Shape: In TMS, asymmetric (e.g., monophasic) or optimized unidirectional pulses can offer superior directional selectivity for activating specific neural populations compared to symmetric biphasic pulses [10]. Consider using algorithmic waveform optimization to design pulses that maximize activation in the target region while minimizing off-target effects [9].

- Utilize Current Steering: If using multiple electrodes, employ bipolar or multipolar configurations to steer the electric field. The shape of the electrical field is determined by the arrangement of anodes and cathodes, which can be programmed to focus current on the target [33].

- Adjust Active Electrode Contact Size and Configuration: Using a smaller active electrode contact can help concentrate current density. For spinal cord stimulation, carefully selecting and configuring the anodes and cathodes on a multi-contact lead can shape the field of paresthesia to cover the painful area [33].

FAQ 3: My stimulation is causing patient discomfort or skin irritation. What steps should I take?

- Ensure Charge Balancing: Unbalanced biphasic or monophasic waveforms can lead to a net DC current, causing electrochemical reactions at the electrode site that lead to skin irritation and potential burns. Always use a accurately charge-balanced biphasic waveform [30] [32].

- Incorporate an Interphase Interval: A short interval (e.g., 50 µs) between the cathodic and anodic phases of a biphasic pulse can allow the membrane capacitance to partially discharge, potentially improving the safety and comfort of the subsequent balancing phase [32].

- Reduce Charge Density: Lower the stimulation amplitude or pulse width. Charge density (amount of charge per unit area per phase) is a key factor in tissue damage. Calculate your charge density and ensure it is within safe limits for your electrode type and tissue.

- Check Electrode Contact and Gel: Ensure electrodes are properly attached with uniform contact. Use high-quality conductive gel to prevent hot spots from uneven current flow.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for Stimulation Research

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Programmable High-Voltage Stimulator | A stimulator capable of generating biphasic, current-controlled pulses with a high compliance voltage (e.g., ±150 V) is essential for transcutaneous stimulation to overcome high skin impedance [32]. |

| Digital Potentiometer | Allows for real-time, programmatic control of stimulation amplitude via serial commands, which is crucial for closed-loop experimental paradigms [32]. |

| Multi-Scale Neuron Modeling Software (e.g., SimNIBS, NEURON) | Software that integrates realistic head models and neuron morphology to simulate the effects of electric fields on neural populations, enabling in-silico waveform testing and optimization [9]. |

| Surface EMG System | For recording motor-evoked potentials (MEPs) to quantitatively assess the output of motor stimulation protocols [31]. |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) Algorithm | An intelligent optimization algorithm used to automatically identify the best waveform parameters for a given objective, such as maximizing stimulation selectivity [9]. |

FAQs: Core Concepts for Researchers

Q1: What are the fundamental differences between SSES and OSES? SSES and OSES are advanced paradigms designed to overcome the limited spatial selectivity of Conventional Monopolar Epidural Stimulation (CMES). SSES uses multiple electrode contacts in bipolar configurations to shape the electric field spatially. In contrast, OSES controls the orientation of the electric field gradient relative to the spinal cord's neuroanatomy, typically using three contacts with currents following sinusoidal functions with 120° phase offsets to steer the field direction [34]. The core difference is that SSES focuses on the location of the field, while OSES focuses on its directional alignment with target neural pathways.

Q2: What is the primary quantitative evidence for superior selectivity with these paradigms? Evidence comes from analyses of Spinally Evoked Motor Potentials (SEMPs). Research shows that the amplitudes of SEMPs in hindlimb muscles significantly depend on the orientation of the applied electric field. Both SSES and OSES provide more selective control over SEMP amplitudes compared to CMES, as measured by the variation in response amplitudes across different stimulation configurations and orientations [34].

Q3: In what key experimental context are OSES paradigms typically applied? While the core principle is universal, the OSES paradigm was pioneered and is extensively used in Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) research to selectively activate axonal pathways based on their orientation [35] [36]. This principle is directly translatable to spinal cord applications, where the goal is to target specific dorsal roots or other oriented structures. The foundational concept is that the maximal activation of axons occurs when the electric field gradient is oriented parallel to them [35].

Q4: What are the technical requirements for implementing OSES? Implementing OSES requires:

- A multichannel electrode array: A minimum of three electrode contacts is needed to define a plane for field orientation. Recent research has expanded this to tetrahedral (4-contact) probes for full 3D orientation control [36].

- An independent current-source stimulator: The system must deliver independently controlled currents to each channel, with the ability to precisely set amplitudes based on sinusoidal functions for field steering [34] [35].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Q1: We are not observing the expected variation in muscle responses with different OSES angles. What could be wrong?

- Cause 1: Incorrect lead placement relative to the target neuroanatomy. The orientation of the electrode array must align with the anatomical plane containing the target fibers.

- Solution: Verify array placement using fluoroscopy or other imaging techniques. Computational modeling of the electric field based on your specific implant geometry can help determine the optimal placement [35].

- Cause 2: Inaccurate current distribution across the electrodes.

- Solution: Recalibrate your stimulator. For OSES, ensure the relative current amplitudes (I1, I2, I3) precisely follow the functions:

I1 = I0 sin(Φ),I2 = I0 sin(Φ + 120°),I3 = I0 sin(Φ - 120°), whereI0is the amplitude andΦgoverns the stimulation angle [34] [35].

Q2: Our experimental results show high variability in SEMP latencies and amplitudes.

- Cause 1: Unstable electrode array position (lead migration).

- Solution: Ensure the array is securely fixed during implantation. In percutaneous setups, lead migration is a known challenge; regularly verify position via fluoroscopy, especially after patient movement [37].

- Cause 2: Suboptimal stimulation parameters or configuration.

- Solution: Systematically perform "spinal mapping." Test a wide range of electrode configurations (cathode/anode arrangements), pulse widths (e.g., 0.5 ms), and current amplitudes (e.g., 0.2-1.2 mA in 0.1 mA increments) to identify the optimal settings for your specific experimental goals [34] [37].

Q3: How do we define and identify the early (ER) and middle (MR) responses in SEMP data?

- Solution: Manually or algorithmically analyze the latency from the stimulus artifact.

- Early Responses (ER): Typically occur within a latency window of 1.5 to 4.5 ms. These are often attributed to the direct activation of motor axons.

- Middle Responses (MR): Typically occur within a latency window of 4.5 to 10.5 ms. These represent the activation of spinal circuits, such as mono- or disynaptic reflexes [34]. For analysis focused on spinal network activation, the MR is often the response of interest.

Table 1: Comparison of Epidural Stimulation Paradigms

| Paradigm | Abbreviation | Electrode Configuration | Key Mechanism | Key Finding in Preclinical Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Monopolar EES | CMES | Single contact with a distant reference | Broad, non-selective activation | Baseline for comparison; lower spatial selectivity [34] |

| Spatial-Selective EES | SSES | Multiple contacts in 8+ bipolar configurations | Spatial shaping of the electric field | Improved selective control of SEMP amplitudes compared to CMES [34] |

| Orientation-Selective EES | OSES | Three contacts with phase-offset currents | Steering the electric field gradient | SEMP amplitudes vary systematically with the stimulation angle, allowing selective activation [34] |

| 3D Orientation-Selective DBS | 3D-OSS | Tetrahedral (4-contact) probe | 3D steering of the electric field | Evoked responses in a monosynaptically connected brain region (amygdala) depend on stimulation field orientation [36] |

Table 2: Typical Experimental Parameters for Rodent SSES/OSES Studies

| Parameter | Typical Setting | Notes / Range |

|---|---|---|

| Animal Model | Adult Sprague Dawley rats (300-350 g) | Common model for initial proof-of-concept studies [34] |

| Pulse Width | 0.5 ms | Standard for neuromodulation [34] |

| Stimulation Frequency | 0.5 Hz (for mapping) | Allows for recovery between pulses and clear SEMP analysis [34] |

| Current Amplitude | 0.2 - 1.2 mA | Tested in 0.1 mA increments to establish response thresholds [34] |

| Pulses per Trial | 10 | Allows for averaging of responses to improve signal-to-noise ratio [34] |

| Data Analysis | Amplitude & Latency of SEMPs | Amplitudes are often normalized as a percentage of the maximal response for comparison [34] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Orientation-Selective Stimulation (OSES)

This protocol outlines the steps to set up and run an OSES experiment based on established methodologies [34] [35].

- Electrode Implantation: Implant a multi-contact electrode array (minimum 3 contacts for 2D, 4 for 3D) in the epidural space over the target spinal cord segment (e.g., lumbosacral enlargement for lower limb motor control) or deep brain region.

- Stimulator Setup: Connect the electrode contacts to a multi-channel, independent current-source stimulator (e.g., an 8-channel system like the STG4008 from Multichannel Systems).

- Define Stimulation Angles: Determine the set of angles (Φ) you wish to test (e.g., from 0° to 360° in 45° increments).

- Calculate Current Amplitudes: For each angle Φ, calculate the current for each of the three channels using the formulas:

I1 = I0 sin(Φ)I2 = I0 sin(Φ + 120°)I3 = I0 sin(Φ - 120°)whereI0is your desired peak current amplitude.

- Deliver Stimulation: For each angle, deliver a train of pulses (e.g., 10 pulses at 0.5 Hz) with the calculated current values for each channel.

- Record Responses: Simultaneously record electromyography (EMG) from target muscles (e.g., Tibialis Anterior, Gastrocnemius) or neural signals.

- Data Analysis: Analyze the amplitude and latency of the evoked responses (SEMPs) for each stimulation angle to identify the orientation that produces the most selective or robust activation.

Protocol 2: Spinal Mapping for Functional Configuration

This protocol is critical for identifying the optimal stimulation parameters to enable specific motor functions in SCI models [37].

- Lead Implantation: Permanently or temporarily implant a percutaneous or paddle lead in the epidural space.

- Systematic Configuration Testing: Test a wide array of electrode configurations, primarily varying the cathode and anode locations. Start with simple configurations (one cathode, one anode) and progress to more complex multi-contact setups.

- Parameter Variation: For promising configurations, vary stimulation parameters such as frequency (e.g., from tonic to 30-100 Hz bursts), pulse width, and amplitude.

- Functional Assessment in Multiple Contexts:

- Supine: Assess for induced tonic extensor activity or voluntary limb movement.

- Upright Supported (Standing Frame): Refine configurations that promote trunk stability and lower limb extension.

- Parallel Bars / Exoskeleton: Test the ability of the configuration to facilitate weight-bearing standing, sit-to-stand transitions, and stepping.

- Iterative Refinement: The mapping process is iterative. Configurations identified in one posture (e.g., supine) must be refined in the target functional posture (e.g., standing). An "interim mapping phase" is often required to transition from one function (e.g., standing) to another (e.g., stepping) [37].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Equipment for SSES/OSES Research

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-channel Stimulator | Delivers precise, independent currents to multiple electrodes for SSES/OSES. | STG4008 (Multichannel Systems); A-M Systems isolators with National Instruments DAC [34] [35] |

| Custom Electrode Arrays | Implantable probes for delivering oriented or spatially selective fields. | 4-channel custom arrays (SSES/OSES) [34]; Tripolar tungsten electrodes (OSS DBS) [35]; Tetrahedral 4-wire probes (3D-OSS) [36] |

| Electromyography (EMG) System | Records spinally evoked motor potentials (SEMPs) from target muscles. | Bipolar needle electrodes; systems from Medtronic or Lab Chart (AD Instruments) for amplification/filtering [34] |

| Fluoroscopic Guidance System | Ensures accurate initial placement and monitors migration of percutaneous leads. | Standard clinical or preclinical C-arm system [37] |

| Computational Modeling Software | Models the electric field distribution for predicting neural activation and optimizing array design. | Used to analyze axonal excitability for varied electric field orientation [35] |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for SSES/OSES Optimization

Diagram 2: Signaling Pathways in Epidural Stimulation

Intelligent Optimization Algorithms and Multi-Scale Neuron Models for Waveform Design

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: Why does my optimization algorithm fail to converge to a waveform that improves stimulation selectivity?

- Problem: The algorithm stalls, produces minimal improvement in the selectivity index (

f1), or suggests physically unrealistic waveform parameters. - Solution: This is often related to an inadequate objective function or incorrect parameter boundaries.

- Review the Selectivity Index Calculation: Ensure your objective function, which quantifies stimulation precision, correctly represents the biological target. The selectivity index (

f1) is often defined as the ratio of activation thresholds in the target region versus the total stimulated area [9]. A miscalculation here will misguide the optimizer. - Check Parameter Constraints: The parameters for the induced electric field waveform (e.g., voltage levels

V1-V4and pulse widthspw1-pw4) must be bounded by the physical limits of your TMS circuit topology [9]. Overly generous boundaries can lead to solutions that are not implementable. - Adjust Algorithm Hyperparameters: If using an algorithm like Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), the convergence is sensitive to hyperparameters like swarm size and learning factors. Fine-tuning these may be necessary for your specific problem landscape [9] [38].

- Review the Selectivity Index Calculation: Ensure your objective function, which quantifies stimulation precision, correctly represents the biological target. The selectivity index (

FAQ 2: How can I validate that my multi-scale neuron model is responding realistically to the optimized waveform?

- Problem: Uncertainty about whether the model's prediction of neuronal activation is physiologically accurate.

- Solution: Employ a multi-faceted validation strategy.

- Compare to Known Results: Test your model with standard, well-documented waveforms (e.g., monophasic, biphasic) and compare the resulting activation thresholds and spatial patterns against published experimental or simulation data [39].

- Inspect Subcellular Responses: Use a toolbox like NeMo-TMS to simulate subcellular processes, such as calcium dynamics in dendrites. A realistic model should show calcium accumulation consistent with known plasticity-inducing protocols [39].