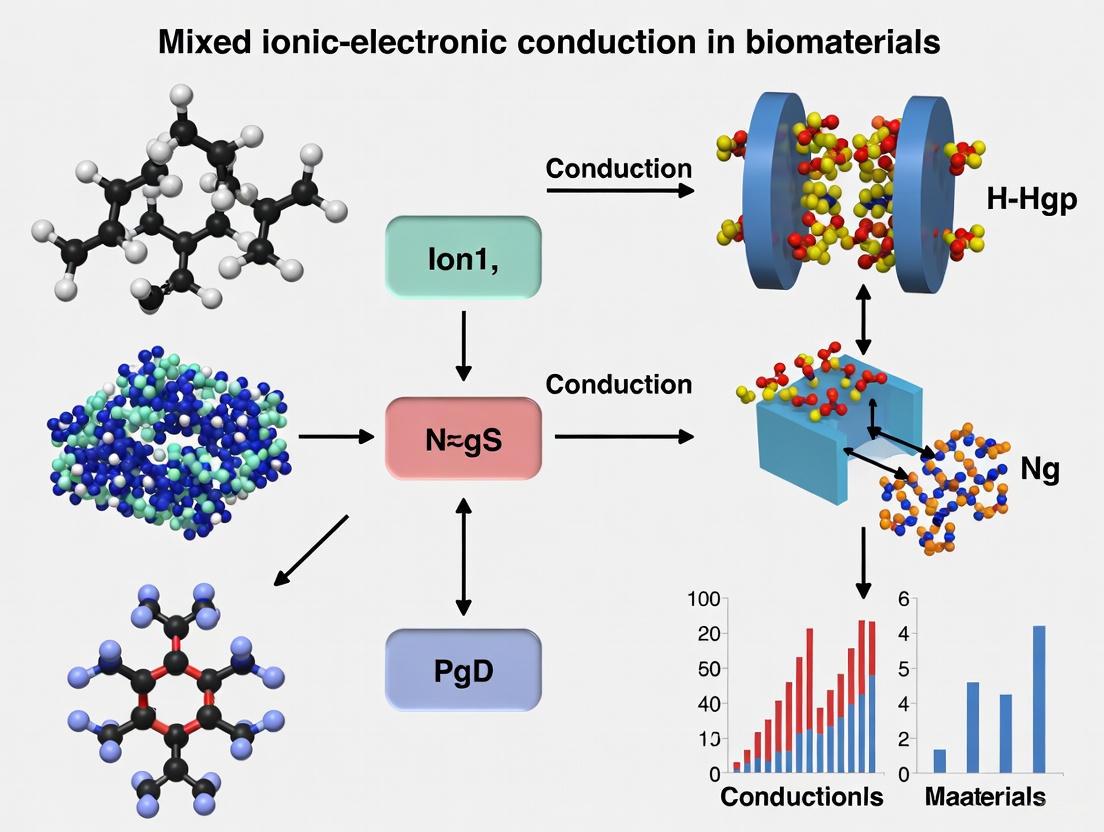

Mixed Ionic-Electronic Conduction in Biomaterials: Fundamentals, Applications, and Future Frontiers in Bioelectronics

This article comprehensively explores the burgeoning field of mixed ionic-electronic conduction (MIEC) in biomaterials, a key technology enabling seamless communication between biological ionic signals and electronic devices.

Mixed Ionic-Electronic Conduction in Biomaterials: Fundamentals, Applications, and Future Frontiers in Bioelectronics

Abstract

This article comprehensively explores the burgeoning field of mixed ionic-electronic conduction (MIEC) in biomaterials, a key technology enabling seamless communication between biological ionic signals and electronic devices. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we delve into the fundamental mechanisms of coupled ion and electron transport in organic materials (OMIECs), review cutting-edge synthesis and characterization methodologies, and highlight transformative applications in bioelectronics, neuromorphic computing, and biosensing. The scope further addresses critical challenges in material stability and performance optimization, compares emerging material classes, and validates performance through advanced operando characterization and computational modeling, providing a holistic resource for advancing next-generation biomedical technologies.

The Fundamentals of Mixed Ionic-Electronic Conduction: Principles and Material Classes for Biointerfacing

Defining Mixed Ionic-Electronic Conductors (MIECs) and OMIECs

Mixed Ionic-Electronic Conductors (MIECs) are a class of materials capable of simultaneously conducting both ions and electrons/holes within a single phase [1]. This dual conduction capability enables the transport of formally neutral species within a solid, facilitating mass storage and redistribution, which is critical for numerous electrochemical applications [1]. The electrical conductivity (σ) of any material is the sum of contributions from all mobile charged species: electronic components (electrons σe and holes σh) and ionic charge carriers (σion) [2]. This relationship is expressed as: σ = σe + σh + σion = e0(nμn + pμp) + ∑izie0Niμi, where n, p, and Ni represent the concentrations of electrons, holes, and ionic species, respectively, and μn, μp, and μi denote their respective mobilities [2].

The relative contribution of each charge carrier is quantified by its transference number (ti ≈ σi/σ) [2]. For purely electronic conductors, the sum of electron and hole transference numbers (te + th) approaches unity, while for pure ionic conductors, ti ≈ 1. True MIECs exhibit significant contributions from both ionic and electronic charge carriers, making them distinct from materials where one type of conduction dominates [2]. This mixed conduction behavior enables rapid solid-state reactions and is particularly valuable in electrochemical devices such as fuel cells, batteries, sensors, and permeation membranes [1].

Organic Mixed Ionic-Electronic Conductors (OMIECs) represent an emerging subclass of MIECs based on organic materials, particularly conjugated polymers [3] [4]. These materials combine the advantages of organic semiconductors—including solution processability, mechanical flexibility, chemical tunability, and biocompatibility—with the unique capability to transport both ionic and electronic charge carriers [3] [4]. The most well-studied OMIEC is poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS), where PEDOT provides electronic conduction through its conjugated backbone while PSS enables ionic transport [4]. OMIECs operate at low bias voltages (<1 V) and their charge carrier concentration can be finely controlled through electrochemical doping, making them particularly suitable for bioelectronic applications [5] [3].

Charge Transport Mechanisms and Material Classifications

Fundamental Transport Physics

In MIECs, ionic and electronic transport occur through distinct yet potentially coupled mechanisms. Ionic conduction in oxide-based MIECs typically occurs via a hopping mechanism through vacant lattice sites, exhibiting thermal activation behavior described by σion = (σ0/T)exp(-EA/kT), where T is absolute temperature, σ0 is a constant, and EA is the activation energy [2]. In perovskite-structured oxides, oxygen ion conduction proceeds primarily through oxygen vacancies or interstitial oxygen ions, which are considered defects relative to the ideal crystal structure [2].

Electronic conduction in MIECs follows semiconductor physics principles, with conductivity dependent on both charge carrier concentration and mobility [2]. In organic OMIECs, electronic transport occurs through a complex interplay of intrachain transport along conjugated backbones and interchain hopping between adjacent chains or conjugated segments [3]. The efficiency of this process depends critically on backbone planarity, π-π interactions, and the degree of structural order [4].

The oxygen exchange reaction with the ambient gas phase in oxide MIECs is represented in Kröger-Vink notation as: OOx ⇌ VO•• + 2e' + ½O2 [2]. This reaction illustrates how oxygen vacancy concentration and electronic charge carriers are interrelated, demonstrating the inherent coupling between ionic and electronic defects in these materials.

Material Classifications and Structures

MIECs can be broadly categorized into several material classes based on their composition and structure:

Inorganic MIECs: These include perovskite oxides (e.g., SrTiO3, (La,Ba,Sr)(Mn,Fe,Co)O3-d, La2CuO4+d), fluorite structures (e.g., CeO2), and chalcogenides (e.g., Ag2+δS, Ag2+δSe) [1] [6]. These materials are typically nonstoichiometric oxides, with perovskite structures being particularly common due to their ability to accommodate various ion substitutions that enhance both ionic and electronic conductivity [1].

Organic MIECs (OMIECs): This category includes conjugated polymers (e.g., PEDOT:PSS, p(g2T-TT)), small molecules, and organic-inorganic hybrids [3] [4] [7]. These materials can be further classified as single-phase systems, where both ionic and electronic conduction occur within a continuous phase, or two-phase systems, where ion-conducting and electron-conducting phases form separate but interpenetrating networks [5].

Composite/Heterogeneous MIECs: These are multiphase materials consisting of mixtures of distinct ionic and electronic conducting phases [1]. A prominent example is LSM-YSZ, comprising lanthanum strontium manganite (LSM) infiltrated onto a Y2O3-doped ZrO2 scaffold, which creates triple phase boundaries (TPBs) that enhance catalytic activity [1].

Table 1: Classification of Mixed Ionic-Electronic Conducting Materials

| Material Class | Examples | Ionic Charge Carrier | Electronic Charge Carrier | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perovskite Oxides | SrTiO3, LSCF (LaSrCoFeO) | O²⁻ vacancies | Holes (p-type) | SOFC cathodes, oxygen membranes |

| Fluorite Oxides | Doped CeO2 | O²⁻ vacancies | Electrons (n-type) | SOFC electrolytes |

| Chalcogenides | Ag₂₊δS, Ag₂₊δSe | Ag⁺ ions | Electrons | Sensors |

| Conjugated Polymers | PEDOT:PSS, p(g2T-TT) | Cations (Na⁺, K⁺) / Anions | Holes (p-type) | OECTs, biosensors |

| Lithium Intercalation | LiCoO₂, LiFePO₄ | Li⁺ ions | Electrons | Battery electrodes |

Organic MIEC Charge Transport Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the coupled ionic-electronic charge transport mechanism in organic mixed ionic-electronic conductors:

Charge Transport in OMIECs

This diagram illustrates how electronic transport occurs along the conjugated backbone while ionic transport proceeds through amorphous regions or ion-conducting domains, with coupling occurring through electrochemical doping processes that modulate electronic charge carrier concentration [3] [4].

Quantitative Properties and Performance Parameters

Key Performance Metrics

The performance of MIECs is characterized by several quantitative parameters that determine their suitability for specific applications:

Conductivity Values: The absolute values of ionic (σion) and electronic (σe, σh) conductivity, typically measured in S/cm [2]. High-performance MIECs for fuel cell applications often demonstrate ionic conductivities > 0.01 S/cm and electronic conductivities > 1 S/cm at operating temperatures [2].

Transport Numbers: The transference numbers for ionic (tion) and electronic (te, th) charge carriers, which sum to unity (tion + te + th = 1) [2]. These values determine whether a material behaves primarily as an ionic conductor, electronic conductor, or true mixed conductor.

Oxygen Permeation Flux: For MIECs used in oxygen separation membranes, the oxygen permeation rate (typically in mL/min·cm² or mol/s·cm²) is a critical performance metric [2].

Area Specific Resistance (ASR): Particularly for SOFC cathode materials, ASR (in Ω·cm²) quantifies the electrode's resistance to oxygen reduction reactions [2]. MIEC cathodes typically exhibit significantly lower ASR values compared to purely electronic conducting cathodes, especially at reduced operating temperatures (500-700°C) [2].

Volumetric Capacitance (C*): For OMIECs used in organic electrochemical transistors (OECTs), the volumetric capacitance (in F/cm³) determines the charge storage capacity and directly influences transconductance [3].

Charge Carrier Mobility (μ): The mobility of electronic charge carriers (in cm²/V·s) in OMIECs determines the speed of electronic transport and is a key factor in OECT performance [3].

Table 2: Representative Conductivity Values for Different MIEC Classes

| Material | Ionic Conductivity (S/cm) | Electronic Conductivity (S/cm) | Dominant Ionic Carrier | Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSCF | ~0.1 | ~10² | O²⁻ | 800 |

| Doped CeO₂ | ~0.01 | ~10⁻³ (air) to ~1 (reducing) | O²⁻ | 800 |

| Ag₂₊δS | ~1 | ~10² to ~10⁴ | Ag⁺ | >200 |

| PEDOT:PSS | ~10⁻³ | ~10² | Cations (Na⁺, K⁺) | 25 |

| p(g2T-TT) | ~10⁻⁴ | ~10⁻¹ to ~10¹ | Anions | 25 |

Environmental Dependencies

The conduction properties of MIECs exhibit strong dependencies on environmental conditions, particularly temperature and oxygen partial pressure (pO₂) [2]. For oxide MIECs, the electronic conductivity follows characteristic pO₂ dependencies: σn ∝ pO₂^(-1/n) for n-type conduction and σp ∝ pO₂^(1/n) for p-type conduction, where n is typically 4 or 6 depending on the dominant defect equilibria [6]. The total conductivity can be expressed as σ = σi + σn⁰exp(pO₂^(-1/n)) + σp⁰exp(pO₂^(1/n)), where σi represents the pO₂-independent ionic conductivity [6].

This pO₂ dependence creates distinct conduction regimes: at low pO₂, n-type electronic conduction dominates; at intermediate pO₂, ionic conduction prevails; and at high pO₂, p-type electronic conduction becomes significant [6]. This behavior is illustrated by the conductivity profile of acceptor-doped strontium titanate (SrTi₁₋ₓFeₓO₃₋δ), which shows clear n-type, ionic, and p-type conduction regions as pO₂ increases [2].

Experimental Characterization Methodologies

Electrical Characterization Techniques

Comprehensive characterization of MIECs requires multiple experimental approaches to deconvolute ionic and electronic contributions:

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): This powerful technique measures the impedance of a material over a range of frequencies, allowing separation of bulk, grain boundary, and electrode contributions to the overall resistance [2]. EIS data analyzed using equivalent circuit modeling can provide quantitative values for ionic and electronic conductivities, along with characteristic relaxation times [2].

DC Polarization Methods: Using ionically or electronically blocking electrodes, DC polarization can separate ionic and electronic conductivities by measuring steady-state currents [2]. The transference number can be determined from the ratio of electronic current to total current or vice versa, depending on electrode configuration.

Four-Point Probe Measurements: For materials with predominantly electronic conduction, four-point probe methods provide accurate electronic conductivity measurements by eliminating contact resistance effects.

Oxygen Permeation Measurements: For oxygen-conducting MIECs, oxygen flux through dense membrane samples is measured as a function of temperature and oxygen partial pressure gradient, providing direct information about oxygen transport properties [2].

Structural and Compositional Analysis

Advanced characterization techniques provide insights into the structure-property relationships in MIECs:

X-ray Fluorescence (XRF): Provides quantitative elemental composition, including ion-to-monomer ratios in OMIECs following electrolyte exposure [7].

Grazing Incidence X-ray Scattering (GIWAXS/GISAXS): Reveals microstructure, crystallinity, and molecular packing in OMIEC thin films, along with ion segregation at nanometer length scales [3] [7].

Electrochemical Quartz Crystal Microbalance with Dissipation Monitoring (EQCM-D): Simultaneously measures mass changes and viscoelastic properties during electrochemical doping, providing direct correlation between ion influx/outflux and charge injection [3].

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Determines chemical composition and oxidation states at surfaces and interfaces, particularly useful for characterizing doped states in OMIECs [7].

Experimental Workflow for OMIEC Characterization

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive experimental workflow for characterizing organic mixed ionic-electronic conductors:

OMIEC Characterization Workflow

This comprehensive characterization workflow enables researchers to establish critical structure-property-performance relationships in OMIECs, guiding material optimization for specific applications [3] [7].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Successful research on mixed ionic-electronic conductors requires access to specialized materials, characterization equipment, and synthetic resources. The following table details key research reagent solutions and their applications in MIEC development and testing:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for MIEC Investigation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specific Types | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS | Benchmark OMIEC material; conductive polymer blend with mixed conduction properties | Clevios PH1000, Orgacon; often modified with ethylene glycol or dimethyl sulfoxide for enhanced conductivity | ||

| Ionic Liquids | Electrolytes for characterizing ion transport and electrochemical doping | EMIM-TFSI, BMIM-BF4; provide wide electrochemical windows and tunable ion sizes | ||

| Solid Oxide Precursors | Synthesis of inorganic MIEC powders and ceramics | SrCO3, TiO2, La2O3, Co3O4, Fe2O3 for perovskite synthesis; CeO2, Gd2O3 for fluorite materials | ||

| Supporting Electrolytes | Aqueous electrolytes for OMIEC characterization | NaCl, KCl, LiClO4 in deionized water; vary concentration to study ion size and concentration effects | ||

| Blocking Electrodes | Separation of ionic and electronic conduction contributions | Pt | MIEC | Pt for electronic blocking; ion-blocking electrodes based on materials impermeable to specific ions |

| Solvent Additives | Morphology control in OMIEC thin films | Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), ethylene glycol (EG), surfactants; enhance conductivity and modify nanoscale structure | ||

| Dopant Precursors | Control of electronic and ionic charge carrier concentrations | FeCl3 for p-doping; hydrazine for n-doping; lithium salts for Li⁺ conduction studies | ||

| Crosslinkers | Stabilization of OMIEC films in aqueous environments | (3-glycidyloxypropyl)trimethoxysilane (GOPS); enhance operational stability in bioelectronic applications |

Applications in Biomaterials Research and Bioelectronics

The unique properties of OMIECs make them particularly valuable for biomaterials research and bioelectronic applications, where their mixed conduction capability enables seamless interfacing between electronic devices and biological systems that primarily communicate through ionic signals [4].

Bioelectronic Sensors and Interfaces

OMIECs serve as ideal materials for bioelectronic sensors due to their ability to transduce biological ionic signals into electronic outputs [3] [4]. Key applications include:

Organic Electrochemical Transistors (OECTs): OMIECs form the channel material in OECTs, where a gate voltage controls the doping state and conductivity of the channel, enabling highly sensitive detection of biological analytes [5] [3]. OECTs based on PEDOT:PSS and other OMIECs have demonstrated exceptional sensitivity in detecting biomarkers in sweat, tears, and other biological fluids [3].

Neural Interfaces: OMIECs facilitate communication between electronic devices and neural tissue, enabling recording and stimulation of neural activity [4]. Their soft mechanical properties reduce tissue inflammation and improve long-term stability compared to traditional metallic electrodes [4].

Biosensors: Functionalized OMIECs can incorporate specific recognition elements (enzymes, antibodies, aptamers) for selective detection of target analytes, with the mixed conduction enabling direct electrochemical readout of binding events [4].

Neuromorphic Devices

The electrochemical doping dynamics in OMIECs closely resemble synaptic function in biological neural networks, making them promising candidates for neuromorphic computing applications [3] [4]. OMIEC-based synaptic transistors can emulate key neural functions including:

Short-term and Long-term Plasticity: The timescales of ion transport and retention in OMIECs can be engineered to mimic both transient and persistent synaptic weight changes [4].

Spike-timing-dependent Plasticity (STDP): The history-dependent doping behavior in OMIECs enables implementation of STDP learning rules, fundamental to unsupervised learning in neural networks [4].

Multi-state Memory: Analog conductance states in OMIEC devices can represent synaptic weights with higher fidelity than binary memory elements, potentially enabling more efficient implementation of artificial neural networks [4].

Therapeutic Applications

OMIECs show promise in several therapeutic applications within biomaterials research:

Drug Delivery Systems: OMIEC-based devices can provide precise spatial and temporal control of drug release through electrochemical modulation of membrane permeability or actuation mechanisms [4].

Tissue Engineering: Conductive scaffolds incorporating OMIECs can provide electrical stimulation to enhance tissue regeneration while maintaining biocompatibility and appropriate mechanical properties [4].

Bioelectronic Medicines: Implantable OMIEC-based devices offer potential for closed-loop therapeutic systems that monitor physiological states and deliver appropriate electrical or chemical interventions [4].

Current Challenges and Research Frontiers

Despite significant progress, several challenges remain in the development and implementation of MIECs, particularly for bioelectronic applications:

Operational Stability: Many OMIECs exhibit performance degradation under ambient conditions or during repeated electrochemical cycling, limiting their commercial implementation [3] [8]. Strategies to improve stability include crosslinking, encapsulation, and development of more robust polymer backbones [3].

Scalable Manufacturing: Transitioning from laboratory-scale synthesis to industrial-scale production while maintaining consistent material properties presents significant challenges [8]. Solution processing techniques such as inkjet printing and roll-to-roll coating show promise for scalable fabrication of OMIEC-based devices [8].

Balanced Mixed Conduction: Achieving optimal balance between ionic and electronic conductivity remains challenging, as molecular design strategies that enhance one type of conduction often compromise the other [8] [4].

Biocompatibility and Biointegration: Long-term biological effects of OMIEC implantation and their integration with biological tissues require further investigation [8]. Research focuses on developing biodegradable OMIECs and surface modification strategies to improve biointegration [9].

Standardization and Characterization: The lack of universally accepted testing protocols hampers direct comparison between different materials and slows technology transfer from research to commercial applications [8]. Developing standardized characterization methodologies represents an important research direction.

Future research will likely focus on developing multifunctional OMIECs with tunable properties, improved environmental stability, and enhanced compatibility with biological systems, ultimately enabling more sophisticated bioelectronic interfaces and sustainable electronic devices [9].

Organic Mixed Ionic-Electronic Conductors (OMIECs) represent an emerging class of polymeric materials that exhibit simultaneous conduction of ions and electrons, enabling a unique interface between biological systems and electronic devices [3] [10]. This dual conduction capability positions OMIECs as fundamental components in advanced bioelectronics, including biosensing platforms, neuromorphic computing systems, and therapeutic drug delivery devices [3]. The core operational mechanisms—electrochemical doping and volumetric capacitance—govern the performance of OMIEC-based devices in biological environments. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to design next-generation biomedical interfaces that translate biological ionic signals into measurable electronic outputs [3]. This technical guide examines the fundamental principles, characterization methodologies, and material design considerations for leveraging these mechanisms in biomaterials research.

Fundamental Principles of Mixed Conduction

Electrochemical Doping in OMIECs

Electrochemical doping is the foundational process that enables OMIECs to transduce ionic signals into electronic currents. Unlike traditional semiconductors that are doped during synthesis, OMIECs undergo in situ doping when exposed to an electrolyte under an applied potential [3] [11]. This reversible process allows dynamic control of the material's electronic properties.

The doping mechanism involves coordinated ionic-electronic charge compensation:

- Ion Injection: Upon application of a gate potential in a transistor configuration, ions from the electrolyte migrate into the bulk of the OMIEC material to maintain electroneutrality [3].

- Polaron Formation: The injected ions stabilize electronic charge carriers (holes or electrons) on the conjugated polymer backbone, forming quasiparticles known as polarons [3].

- Electronic Structure Modulation: This electrochemical doping process significantly alters the electronic structure of the material, increasing its electronic conductivity by several orders of magnitude [11].

In a typical p-type OMIEC (e.g., PEDOT:PSS or P3HT), oxidation of the polymer backbone (hole injection from the electrode) is accompanied by anion insertion from the electrolyte to maintain charge balance [3]. Conversely, reduction would cause cation insertion or anion expulsion. This intricate coupling between ionic and electronic charge carriers enables OMIECs to effectively translate biological ionic fluxes into measurable electronic signals, making them particularly suitable for biosensing and bioelectronic applications [3].

Volumetric Capacitance in OMIECs

Volumetric capacitance (C*) is a critical material property that distinguishes OMIECs from conventional semiconductors and determines their performance in electrochemical devices [12]. Unlike traditional capacitors that store charge at a two-dimensional interface, OMIECs utilize their entire bulk volume for charge storage, enabling exceptionally high capacitance values [12].

The volumetric capacitance arises from:

- Stern Layer Formation: Electrostatic layers form between electronic charge carriers (holes in p-type materials) and their counterions throughout the three-dimensional volume of the material [12].

- Bulk Charge Storage: The interpenetrating networks of ionic and electronic charge carriers allow the entire material volume to participate in charge storage and modulation [3] [12].

- Quantum Contributions: In addition to classical electrostatic effects, quantum mechanical contributions further enhance the capacitance in these nanoscale systems [12].

The significance of volumetric capacitance becomes evident in the performance metrics of Organic Electrochemical Transistors (OECTs), where the transconductance (gₘ) - a key figure of merit for signal amplification - is directly proportional to both volumetric capacitance and charge carrier mobility: gₘ ∝ μC* [3] [12]. This relationship highlights why high volumetric capacitance is essential for developing sensitive biosensors and efficient bioelectronic interfaces.

Table 1: Key Parameters Governing OMIEC Performance

| Parameter | Symbol | Role in OMIEC Operation | Typical Range/Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volumetric Capacitance | C* | Determines charge storage capacity and transconductance | ~100 F/cm³ [12] |

| Electronic Charge Carrier Mobility | μ | Governs electronic conduction efficiency | Varies with material design [3] |

| Ion Diffusion Coefficient | Dᵢ | Controls kinetics of doping process | Measured via moving front experiments [11] |

| Transconductance | gₘ | Key performance metric for signal amplification | gₘ = (Wd/L)μC*(Vₜₕ-V_G) [3] |

Experimental Characterization Methodologies

Operando Characterization Techniques

Understanding the dynamic processes of electrochemical doping requires advanced characterization techniques that can probe material properties under operational conditions. Operando characterization provides real-time insights into structural changes, ion transport, and charge carrier dynamics during device operation [3].

Table 2: Key Operando Characterization Techniques for OMIECs

| Technique | Key Measured Parameters | Insights Gained | Applications in Biomaterials Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| GIWAXS (Grazing-Incidence Wide-Angle X-ray Scattering) | Crystallographic changes, π-π stacking distance, polymer packing | Real-time microstructure evolution during doping/swelling [3] | Monitoring structural stability in physiological environments |

| EQCM-D (Electrochemical Quartz Crystal Microbalance with Dissipation) | Mass changes, viscoelastic properties | Ion/water uptake kinetics and swelling behavior [3] | Quantifying hydrogel-like properties for implantable devices |

| In situ Scanning Probe Microscopy | Morphological changes, surface potential, mechanical properties | Nanoscale mapping of doping front propagation [3] | Interface characterization with biological tissues |

| X-ray Fluorescence Analysis | Element-specific ion distribution | Tracking specific ion transport through polymer matrix [3] | Studying ion selectivity in biological fluid sensing |

Moving Front Experiments for Doping Kinetics

The moving front experiment presents a powerful methodology for quantifying solid-state doping kinetics in OMIECs, particularly relevant for devices operating in biological environments where liquid electrolytes may be constrained [11]. This technique enables direct visualization and measurement of ion transport dynamics through color-changing (electrochromic) OMIECs.

Experimental Protocol:

- Device Fabrication:

- Prepare a thin film of electrochromic OMIEC (e.g., PProDOT) on an ITO-coated glass substrate via spin-coating (20 mg/mL in chloroform, 1500 rpm) [11].

- Partially cover the film with an ion-blocking layer to create a defined interface between doped and undoped regions.

Electrochemical Setup:

- Assemble a solid-state device stack incorporating the OMIEC film, gel electrolyte, and counter electrode [11].

- Apply controlled gate voltages (typically 0-1V) to initiate doping front propagation.

Kinetic Measurement:

- Track the displacement of the visible doping front as a function of time.

- Measure the relationship between front position and square root of time to determine diffusion-controlled kinetics [11].

In situ Mechanical Characterization:

- Integrate nanoindentation to measure modulus and hardness changes across the moving front [11].

- Quantify volumetric swelling strains associated with ion insertion.

This methodology revealed that an externally applied pressure of 2.8 MPa significantly retards front propagation due to stress effects on ion chemical potential and diffusivity [11]. Such insights are crucial for designing OMIEC-based implants that must maintain functionality under mechanical stress in biological environments.

Diagram 1: Moving front experimental workflow for doping kinetics.

Computational Modeling Approaches

Computational modeling provides complementary insights into OMIEC operation at multiple scales, from atomic interactions to device-level performance [3]. The Nernst-Planck-Poisson (NPP) framework has emerged as a particularly valuable approach for predicting device behavior [12].

2D NPP Model Implementation:

- Governing Equations:

- Poisson equation coupling electron and ion phases with explicit volumetric capacitance

- Nernst-Planck equations describing ion and hole transport

- Continuity equations for charge conservation [12]

Critical Parameters:

- Volumetric capacitance (Cᵥ) as fundamental input

- Diffusion coefficients for holes (Dρ) and ions (Dᵢ)

- Fixed anion concentration (for PEDOT:PSS systems) [12]

Validation:

- Quantitative agreement with experimental output currents across gate voltages

- Accurate prediction of potential profiles and charge carrier distributions [12]

This modeling approach highlights that incorporating volumetric capacitance is essential for predictive accuracy, akin to including conductivity in describing current flow [12]. The models successfully capture how higher gate voltages induce channel depletion through reduced hole density (ρ), directly linking molecular-scale processes to device-level performance [12].

Material Design Strategies for Biomaterials Research

Sidechain Engineering

Sidechain engineering offers a powerful approach to tune OMIEC properties for specific bioelectronic applications. The chemical structure of sidechains significantly influences ion transport, hydration, swelling behavior, and ultimately mixed conduction efficiency [3].

Key sidechain design strategies include:

- Ethylene Glycol (EG) Sidechains: Promote ion solvation and transport but may lead to excessive swelling in aqueous environments [3].

- Alkyl Spacers: Incorporation of alkyl segments into glycolated sidechains reduces swelling while maintaining favorable ion transport properties [3].

- Zwitterionic Groups: Sidechains with zwitterionic moieties enhance hydration control and improve compatibility with biological systems [3].

- Ionic Functional Groups: Charged groups attached via alkyl spacers optimize the balance between transconductance and swelling resistance [3].

These molecular-level design principles enable researchers to systematically optimize OMIEC performance for specific biological environments, such as implantable sensors requiring minimal swelling while maintaining high sensitivity to target biomarkers.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for OMIEC Studies

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Significance in Biomaterials Research |

|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS | Benchmark OMIEC material | High mixed conductivity; widely used in biosensors and neural interfaces [12] |

| PProDOT | Model electrochromic OMIEC | Enables visualization of doping fronts; ideal for kinetic studies [11] |

| Gel Electrolytes | Solid-state ion conduction | Mimics physiological environments; enables implantable device testing [11] |

| Zwitterionic Sidechain Polymers | Swelling-resistant OMIECs | Maintains performance in aqueous biological environments [3] |

| Ethylene Glycol Functionalized Polymers | Enhanced ion transport | Optimizes ion uptake for sensitive biomarker detection [3] |

Implications for Biomaterials Research and Drug Development

The fundamental mechanisms of electrochemical doping and volumetric capacitance position OMIECs as transformative materials for biomedical applications. Their unique properties enable:

- High-Sensitivity Biosensing: Efficient conversion of biological ionic signals into electronic outputs enables detection of low concentrations of biomarkers, neurotransmitters, and pathogens [3] [12].

- Neural Interfaces: Mixed conduction facilitates seamless communication between electronic devices and neural tissue, supporting applications in brain-computer interfaces and neuromodulation [3].

- Drug Delivery Monitoring: OECT-based sensors can monitor drug concentration in real-time, providing feedback for personalized therapeutic regimens [12].

- Implantable Devices: The flexibility, biocompatibility, and efficient operation in aqueous environments make OMIECs ideal for chronic implants [3].

Diagram 2: Signal transduction pathway from biological ions to electronic output.

Future research directions should focus on elucidating degradation mechanisms under physiological conditions, developing standardized biocompatibility protocols, and establishing design rules for specific biomedical applications. The integration of advanced operando characterization with computational modeling will accelerate the rational design of OMIEC-based solutions to pressing challenges in drug development and biomedicine [3].

Mixed ionic-electronic conductors (MIECs) represent a cornerstone materials class in modern bioelectronics, enabling seamless translation of signals between the ionic domain of biological systems and the electronic domain of conventional instrumentation. This whitepaper provides a technical examination of three key MIEC material systems: the conjugated polymer poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrene sulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS), glycolated polymers, and conjugated polyelectrolytes. Within biomaterials research, these systems facilitate groundbreaking applications in neural interfaces, cardiac monitoring, biosensing, and drug delivery by combining electronic conductivity with ionic transport capabilities. This guide details fundamental charge transport mechanisms, material processing protocols, and performance characterization methodologies to equip researchers with practical knowledge for advancing bioelectronic device development.

Mixed ionic-electronic conduction refers to the ability of a material to simultaneously transport both electronic charges (electrons and holes) and ionic species (such as Na+, K+, Cl-). This dual conduction capability is exceptionally rare in conventional electronic materials but is critical for creating effective bioelectronic interfaces where biological signals are primarily ionic in nature. In biological environments, MIECs facilitate efficient signal transduction while offering mechanical properties compatible with soft tissues, significantly reducing inflammatory responses compared to traditional rigid electrodes [13].

The unique properties of MIECs have catalyzed advancements across multiple biomedical domains:

- Neural Interfaces: PEDOT:PSS-based electrodes enable high-fidelity brain activity monitoring and modulation with reduced impedance and improved signal-to-noise ratios [13].

- Cardiac Monitoring: Soft ionic-electronic conductive interfaces allow for enhanced intracellular recording of cardiomyocyte action potentials [14].

- Biosensing: Organic electrochemical transistors (OECTs) utilizing PEDOT:PSS channels amplify small biological signals for metabolite detection [15].

- Drug Delivery: Electrically conductive "SMART" hydrogels provide platforms for on-demand therapeutic release [16].

Fundamental Material Systems

PEDOT:PSS

PEDOT:PSS is a polymer complex consisting of positively charged conjugated PEDOT chains and negatively charged insulating PSS chains. This structure creates a polyelectrolyte system where PEDOT provides electronic conductivity through π-electron delocalization, while PSS enables ionic transport and stabilizes the colloidal dispersion in water [13].

Charge Transport Mechanisms: Electronic transport occurs through hopping between localized states in PEDOT-rich domains, while ionic transport involves ion mobility through the hydrated PSS-rich regions. The coupling between these charge carriers enables efficient mixed conduction, which can be modulated by electrochemical doping/de-doping processes [17]. Structural control over nanoscale morphology directly influences both transport pathways, with enhanced π-π stacking improving electronic mobility and hydrated regions facilitating ion diffusion [17].

Key Performance Metrics:

- Electrical Conductivity: Ranges from <1 S/cm for pristine films to >1000 S/cm with secondary doping [13]

- Volumetric Capacitance: ~2.3 F·cm⁻³ for PVA/PEDOT:PSS hydrogels in OECT configurations [15]

- Swelling Ratio: ~180-200% w/w for crosslinked PVA/PEDOT:PSS hydrogels [15]

- Transconductance: ~1.05 μS for hydrogel-based OECTs, critical for signal amplification [15]

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of PEDOT:PSS-Based Materials

| Material Format | Conductivity (S/cm) | Key Application | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pristine Film | <1 | Neural Interfaces | Low impedance, high CIC |

| EG-Doped Film | >1000 | OECT Channels | Enhanced hole mobility |

| PVA Hydrogel | Variable | OECT Channels | C* ~2.3 F·cm⁻³, swelling ~200% |

| Electrodeposited | ~10-100 | Intracellular Recording | Stable electroporation, high SNR |

Glycolated Polymers

Glycolated polymers, particularly polyethylene glycol (PEG) and polyethylene oxide (PEO), constitute another vital MIEC class characterized by ethylene oxide repeating units that solvate and transport ions while exhibiting limited electronic conductivity. These materials serve as solid polymer electrolytes in biomedical applications, leveraging their exceptional ion coordination capability and biocompatibility.

Transport Mechanisms: Ion conduction occurs through segmental motion of polymer chains above the glass transition temperature, creating dynamic pathways for cation transport (typically Li⁺, Na⁺, or K⁺). The ether oxygen atoms in PEG/PEO chains coordinate with cations, facilitating ion dissociation and mobility while inherently blocking electronic conduction [18].

Recent molecular engineering approaches have enhanced glycolated polymer performance:

- Disordered Structure Design: Incorporating rigid hexamethylene diisocyanate (HDI) segments disrupts PEG crystallinity, achieving ionic conductivity approaching 10⁻³ S·cm⁻¹ with Li⁺ transference numbers of 0.88 [18].

- Lewis Acid Group Incorporation: Carbonyl and carboxylate groups capture anions, increasing free cation concentration and improving transference numbers [18].

- Crosslinking Strategies: Balance mechanical stability with ionic conductivity while maintaining biocompatibility [18].

Conjugated Polyelectrolytes

Conjugated polyelectrolytes (CPEs) represent an emerging MIEC class combining π-conjugated backbones for electronic transport with covalently attached ionic side groups for ionic conductivity. This molecular design creates intrinsic mixed conduction pathways within a single polymer chain, offering unique advantages for biological sensing and interfacing.

Structural Characteristics: CPEs feature conjugated backbones (such as polythiophene, polyphenylene, or polyfluorene derivatives) with ionic substituents (typically sulfonate, carboxylate, or ammonium groups). This architecture enables simultaneous electronic transport along the backbone and ionic interactions/counterion transport through side chains [19].

Dimensional Considerations:

- 1D CPEs: Anisotropic charge transport along linear polymer chains, suitable for oriented films and fiber-based electronics [19].

- 2D CPEs: Extended π-conjugation in planar structures enhances electronic conductivity and charge carrier mobility through improved interchain hopping [19].

Experimental Methodologies

PEDOT:PSS Hydrogel Preparation for OECT Applications

Protocol Adapted from PVA/PEDOT:PSS Hydrogel Synthesis [15]

Materials and Equipment:

- Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA, MW 30,000-70,000)

- PEDOT:PSS aqueous dispersion (1.3% w/w)

- Glutaraldehyde (50% aqueous solution)

- Hydrochloric acid (HCl)

- Deionized water

- Magnetic stirrer with heating

- Plastic plates or Petri dishes for casting

Procedure:

- PVA Solution Preparation: Dissolve 5.0 g PVA in 100 mL deionized water under vigorous stirring at 60°C until fully dissolved.

- PEDOT:PSS Incorporation: Add corresponding amount of PEDOT:PSS dispersion to PVA solution (typical formulations: 3%, 12%, or 20% w/w PEDOT:PSS). Stir overnight.

- Crosslinking Initiation: Adjust pH to ~2 using HCl. Acid catalysts promote acetal formation between PVA chains.

- Gelation: Add 0.01 mL glutaraldehyde to 20 mL of PVA/PEDOT:PSS solution. Mix thoroughly.

- Film Casting: Pour solution onto plastic plates and dry at room temperature for 72 hours.

- Post-processing: Hydrate resulting hydrogels in aqueous solution before characterization.

Key Characterization Techniques:

- Swelling Ratio: Measure weight before (wunswollen) and after (wswollen) hydration: Swelling (%) = 100 × (wswollen - wunswollen)/w_unswollen [15]

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy: Evaluate charge transport/transfer properties across frequencies

- In operando Raman Spectroscopy: Monitor doping/de-doping processes during device operation

PEG-Based Solid Polymer Electrolyte Synthesis

Protocol for Disordered PEGH/L4000 Electrolyte [18]

Materials:

- Polyethylene glycol (PEG, Mw = 4000 g·mol⁻¹)

- Hexamethylene diisocyanate (HDI)

- 2,2-dimethylolpropionic acid (DMPA)

- Lithium hydroxide (LiOH)

- Lithium bis(trifluoromethane sulfonimide) (LiTFSI)

- Dibutyltin dilaurate (DBTL) catalyst

- N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, dried with 4Å molecular sieves)

Synthetic Procedure:

- LiDMPA Preparation:

- Combine 0.01 mol DMPA and 0.01 mol LiOH in 10 mL distilled water

- React at 60°C for 4 hours with mechanical stirring

- Dry at 120°C under vacuum for 24 hours to obtain white crystalline product

PEGH Intermediate Synthesis:

- Combine 40 mL DMF, 0.004 mol PEG, 0.008 mol HDI, and 20 μL DBTL in three-neck flask under argon

- React at 80°C for 2 hours with mechanical stirring

PEGH/L Final Product:

- Add 0.0045 mol LiDMPA to PEGH intermediate

- Continue reaction at 80°C for 2 hours under argon atmosphere

- Add LiTFSI at EO:Li⁺ ratio of 20:1 for lithium incorporation

Performance Optimization:

- Disordered Structure: HDI segments disrupt PEG crystallinity, enhancing ion mobility

- Lewis Acid Groups: Carbonyl and carboxylate groups coordinate anions, increasing free Li⁺ concentration

- Characterization: Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy for ionic conductivity, linear sweep voltammetry for stability window, chromoamperometry for Li⁺ transference number

Electrochemical Deposition of PEDOT:PSS for Neural Interfaces

Protocol for Microelectrode Modification [14] [13]

Materials and Equipment:

- Au, Pt, or ITO microelectrodes

- 3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene (EDOT) monomer

- Poly(sodium 4-styrenesulfonate) (PSS, Mw = 70,000)

- Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) or appropriate electrolyte

- Potentiostat/galvanostat with three-electrode configuration

Electrodeposition Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare aqueous solution containing 20 mM EDOT and 1% (w/v) PSS

- Electrochemical Setup: Configure standard three-electrode system with target microelectrode as working electrode, Ag/AgCl reference electrode, and Pt counter electrode

- Potentiostatic Deposition: Apply pulsed potentials: 0.9 V for 50s followed by 0 V for 2s per cycle

- Cycle Optimization: Typically 4-12 cycles depending on desired film thickness and properties

- Post-processing: Rinse modified electrodes with deionized water and characterize

Key Parameters for Intracellular Recording Applications:

- Low Electrode Impedance: PEDOT:PSS coating reduces impedance at 1 kHz by ~90% compared to bare Au electrodes [14]

- High Charge Injection Capacity: Enables stable electroporation for intracellular access

- Biocompatibility: Supports cardiomyocyte adhesion and long-term culture without cytotoxicity

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Mixed Ionic-Electronic Conductor Development

| Reagent/Category | Function/Purpose | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS Dispersions | Primary conductive component | OECT channels, neural electrodes, biosensors |

| Ethylene Glycol (EG) | Secondary dopant for conductivity enhancement | Morphology control in PEDOT:PSS films [17] |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | Hydrogel matrix for mechanical stability | Swellable OECT channels [15] |

| Glutaraldehyde | Crosslinking agent for hydrogel formation | Stabilizing PVA/PEDOT:PSS networks [15] |

| Hexamethylene Diisocyanate (HDI) | Rigid segment for disordered polymer design | PEG-based solid electrolytes [18] |

| LiTFSI Salt | Lithium ion source for ionic conduction | Solid polymer electrolytes for bio-iontronics |

| DMSO/Ethylene Glycol | Co-solvents for morphology control | Enhancing PEDOT:PSS crystallinity [17] |

| Ionic Liquids (EMIM-DCA) | Additives for thermoelectric enhancement | Improving ZT values in conductive polymers [20] |

Charge Transport Mechanisms and Pathways

The fundamental operation of MIECs relies on complex interactions between electronic and ionic charge carriers. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for material design and optimization.

Diagram: Charge Transport Pathways in Mixed Conductors

Advanced Applications in Biomaterials Research

Organic Electrochemical Transistors (OECTs)

OECTs represent one of the most significant applications of MIECs in biomedicine, leveraging ionic modulation of electronic conductivity for ultrasensitive biosensing. In PVA/PEDOT:PSS hydrogel-based OECTs, the swelling capacity (~180-200% w/w) creates an enhanced interface with biological electrolytes, facilitating efficient charge transfer processes [15]. These devices achieve transconductance values of ~1.05 μS with volumetric capacitance of ~2.3 F·cm⁻³, enabling amplification of weak biological signals.

Operation Mechanism: Application of a gate voltage injects ions from the electrolyte into the channel material, modulating hole conductivity in PEDOT through electrochemical doping/de-doping. This coupling between ionic and electronic charge carriers provides signal amplification directly at the biological interface.

Neural Interfaces and Brain Monitoring

PEDOT:PSS-based bioelectronics have revolutionized neural interfacing through materials that match the mechanical properties of brain tissue (Young's modulus ~0.1-10 MPa vs. 1-4 kPa for brain tissue) while providing high electrical conductivity [13]. This mechanical compatibility minimizes shear stress-induced tissue damage during brain micromotion, reducing inflammatory responses and enabling chronic implantation.

Key Advances:

- Flexible Microelectrode Arrays: PEDOT:PSS coatings reduce impedance by ~90%, significantly improving signal-to-noise ratio for neural recording [14] [13].

- Multimodal Monitoring: Integration with optical and electrical stimulation enables comprehensive neural circuit investigation.

- 3D Printing Technologies: Fabrication of customized hydrogel-based bioelectronics with tissue-like mechanical properties.

Intracellular Recording Platforms

PEDOT:PSS-modified electrodes enable high-fidelity intracellular recording of cardiomyocyte action potentials through electroporation-based approaches. The soft ionic-electronic conductive interface establishes stable coupling with cell membranes, allowing transient permeabilization for intracellular access without compromising long-term cell viability [14].

Performance Metrics:

- Stable Electroporation: Maintains recording capability through multiple electroporation cycles over several days

- Enhanced Signal Quality: Significantly improved signal-to-noise ratios compared to conventional metal electrodes

- High-Fidelity Action Potential Capture: Accurate recording of cardiomyocyte electrophysiology with minimal invasion

Future Perspectives and Research Directions

The field of mixed ionic-electronic conduction for biomaterials continues to evolve with several promising research directions emerging:

Multifunctional Bioelectronics: Next-generation interfaces combining sensing, stimulation, and drug delivery capabilities within a single platform will enable comprehensive biological investigation and therapeutic intervention [13] [16].

Advanced Manufacturing: 3D and 4D printing technologies will facilitate creation of patient-specific bioelectronic interfaces with complex architectures and responsive capabilities [13].

Environment-Responsive Systems: "SMART" hydrogels that modulate properties in response to physiological cues will enable autonomous therapeutic adjustment and closed-loop bioelectronic medicine [16].

Hybrid Material Systems: Combining PEDOT:PSS with glycolated polymers and conjugated polyelectrolytes will create composite materials with optimized ionic and electronic transport properties tailored to specific biomedical applications.

As research advances, these material systems will continue to bridge the gap between biological and electronic domains, enabling increasingly sophisticated interfaces for understanding and treating disease, restoring function, and enhancing human health.

This technical guide examines the fundamental coupling between hole chemical potential and ion drift-diffusion in organic mixed ionic-electronic conductors (OMIECs). Within the context of biomaterials research, this interplay enables transformative bioelectronic applications, from implantable medical devices to neuromorphic computing. The charge transport physics governing these materials creates a complex, dynamic system where electronic and ionic charge carriers interact volumetrically, determining device performance metrics including signal propagation velocity, energy dissipation, and amplification characteristics. This whitepaper synthesizes current theoretical frameworks, experimental methodologies, and quantitative structure-property relationships to provide researchers with a comprehensive reference for designing and characterizing next-generation OMIEC-based biomedical technologies.

Organic mixed ionic-electronic conductors represent a critical materials class for bioelectronics due to their unique ability to transduce signals between ionic charge carriers predominant in biological systems and electronic charge carriers used in conventional electronics. This bidirectional transduction capability, combined with inherent mechanical softness, biocompatibility, and facile processing, makes OMIECs ideally suited for creating seamless interfaces between biological tissue and electronic devices [21]. The core physics governing these materials centers on the coupled transport of electronic carriers (electrons and holes) and ionic species (cations and anions) through a polymeric or organic matrix.

In biomaterials research, this mixed conduction enables devices that can sense, stimulate, and interact with biological systems at a fundamental level. Applications range from microelectrode arrays for in vitro and in vivo monitoring, organic electrochemical transistors (OECTs) for signal amplification, neuromorphic circuits that mimic biological information processing, to ultra-conformable wearable electronics and artificial tissues [21]. The performance of all these applications hinges on understanding and controlling the dynamic relationship between hole chemical potential—the thermodynamic driving force for hole transport—and ion drift-diffusion processes that facilitate ionic motion through the material bulk.

Theoretical Foundations

Defining the Hole Chemical Potential

In OMIECs, the hole chemical potential (μₚ) represents the free energy change associated with adding or removing a hole from the system. It governs the direction and magnitude of hole transport under concentration gradients and electric fields. Formally, it relates to the quasi-Fermi energy for holes (εF^(p)) through μₚ = -εF^(p), defining the statistical distribution of holes in available electronic states [22]. For degenerate systems where quantum effects become significant, the current density for holes is expressed as:

[ Jp = \mup p \frac{\partial \varepsilon_F^{(p)}}{\partial x} ]

where μₚ is the hole mobility, p is the hole density, and ∂ε_F^(p)/∂x represents the gradient of the hole quasi-Fermi potential [22]. This formulation differs fundamentally from non-degenerate systems where Maxwell-Boltzmann statistics apply and current follows the classical drift-diffusion form.

Ion Drift-Diffusion Physics

Ion transport in OMIECs occurs through a combination of drift under electric fields and diffusion along concentration gradients. The ionic current density for a species i with charge number z_i can be described by:

[ Ji = -zi \mui ui \nabla \varphi_i ]

where μi is the ionic mobility, ui is the density of ionic vacancies or carriers, and φ_i is the ionic potential [23]. The statistical relation connecting ionic densities to potentials follows specialized statistics—often Blakemore statistics for ionic vacancies to prevent unrealistic accumulation that would destroy the crystal structure [23]. This prevents physically impossible density buildup that would compromise material integrity.

The Coupled System: Poisson and Continuity Equations

The complete charge transport system couples the electrostatic potential with continuity equations for all charge carriers through the Poisson equation:

[ -\nabla \cdot (\varepsilon \nabla \psi) = C + zn un + zp up + \sum{i \in I0} zi ui ]

where ε is the dielectric permittivity, ψ is the electrostatic potential, C is the fixed doping density, and the right-hand side represents the total space charge from electrons (n), holes (p), and ionic species (I₀) [23]. This is self-consistently coupled with continuity equations for each carrier type:

[ \frac{\partial ui}{\partial t} - \nabla \cdot (zi \mui ui \nabla \varphi_i) = G - R ]

where G and R represent generation and recombination terms [23]. The coupling occurs through the statistical relations that connect carrier densities ui to potentials through ui = Ni ℱi(zi(φi - ψ) + ζi), where ℱi is the appropriate statistics function (Fermi-Dirac for electrons/holes, Blakemore for ions) [23].

Table 1: Key Parameters in Coupled Charge Transport Models

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Typical Values/Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hole mobility | μₚ | Measure of hole drift velocity per electric field | Material-dependent (cm²/V·s) |

| Volumetric capacitance | c_v | Charge storage capacity per unit volume | >30 F/cm³ [21] |

| Electronic resistivity | ρ_el | Opposition to electronic current flow | Ω·m |

| Ionic resistivity | ρ_ion | Opposition to ionic current flow | Ω·m |

| Effective density of states | N_i | Available states for carrier occupation | cm⁻³ |

| Charge number | z_i | Number of elementary charges per carrier | Dimensionless |

Fundamental Interplay and Key Metrics

The coupling between hole chemical potential and ion drift-diffusion creates a rich physical system where changes in one potential immediately affect the distribution and transport of the other carrier type. When a potential is applied to an OMIEC channel, it alters the local charge distribution through ejection or insertion of mobile ions, which electrostatically couple with electronic carriers, generating capacitive currents that enable signal transduction [21]. This volumetric capacitance (c_v) becomes a critical parameter linking ionic and electronic domains.

The signal propagation velocity in OMIEC channels, a key performance metric for bioelectronic applications, is dominated by the ratio μel/cv at relevant frequencies, making this combination a crucial figure of merit for benchmarking material formulations [21]. This relationship emerges from transmission line analysis of OMIEC channels, where the propagation constant γ is given by:

[ \gamma = \sqrt{\frac{j\omega cv \rho{el}}{1 + j\omega cv \rho{ion} t_h^2}} ]

where ω is the angular frequency, and th is the channel thickness [21]. The phase velocity of signal transmission then becomes directly proportional to μel/c_v, highlighting the fundamental tradeoff between electronic mobility and capacitive coupling.

Quantitative Relationships and Material Design Rules

The performance of OMIEC devices in biomedical applications depends critically on quantifiable relationships between material parameters and operational characteristics. Through rigorous modeling and experimental validation, researchers have established key design rules that govern device behavior.

Table 2: Performance Dependencies on Material Parameters in OMIECs

| Performance Metric | Governing Equation/Relationship | Impact on Bioelectronic Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Signal propagation velocity | vphase ∝ μel/c_v | Determines maximum operating frequency and response time [21] |

| Drain current saturation | Enhanced by contact asymmetry (AD/AS) | Enables high-gain amplification in transistor circuits [24] |

| Transconductance | gm ∝ μel · c_v · (W/L) | Determines signal amplification capability in OECTs [24] |

| Phase velocity | v_phase = ω/Im(γ) | Controls signal transmission speed along OMIEC channels [21] |

| Energy dissipation | P_diss ∝ J²ρ | Affects device heating and power efficiency in implants [21] |

These quantitative relationships enable rational design of OMIEC-based bioelectronic devices. For instance, maximizing signal propagation velocity requires simultaneously high electronic mobility and low volumetric capacitance—a materials design challenge that must be addressed through molecular engineering of the conductor matrix. Similarly, achieving sharp saturation in transistor output characteristics—critical for high-gain amplification—can be controlled through geometric design of contact asymmetry rather than solely through materials chemistry [24].

The volumetric capacitance (c_v) represents a composite parameter with potential contributions from chemical capacitance (related to entropy changes during carrier accumulation), quantum capacitance (dependent on the electronic density of states), and electrostatic capacitance (from nanoscale phase separation creating ionic and electronic subphases) [21]. The relative magnitude of these contributions varies with material composition and processing, providing multiple engineering handles for tuning device performance.

Experimental Methodologies and Characterization Techniques

Device Fabrication and Geometrical Control

Creating high-performance OMIEC devices requires precise control over material deposition and device geometry. For complementary circuits using a single organic material, asymmetric contact areas prove essential. The experimental workflow involves:

- Substrate Preparation: Clean and pattern substrate surfaces appropriate for biological integration (e.g., flexible, biocompatible polymers).

- OMIEC Layer Deposition: Spin-coat or print the mixed conducting polymer (e.g., PEDOT:PSS) with thickness control typically between 100-500 nm.

- Asymmetric Contact Patterning: Create source and drain contacts with controlled area asymmetry using photolithography or shadow masking, ensuring the lower-potential contact has smaller area [24].

- Ion Reservoir Integration: For internal ion-gated transistors (IGTs), incorporate mobile ion reservoirs within the channel to reduce ionic transit time [24].

- Encapsulation: Apply biocompatible encapsulation layers where necessary for implantable applications.

Electrical Characterization of Transport Properties

Comprehensive electrical characterization reveals the fundamental interplay between hole chemical potential and ion transport:

Output and Transfer Characteristics: Sweep drain-source voltage (VDS) at various gate voltages (VG) to map transistor operation across quadrants. Asymmetric contact geometries dramatically enhance saturation in specific quadrants—smaller drain contact area (AD < AS) improves saturation in the 3rd quadrant, enabling p-type-like operation from hole-conducting polymers [24].

Impedance Spectroscopy: Measure complex impedance over frequency (typically 1 Hz - 10 MHz) to extract volumetric capacitance (cv), ionic resistance (ρion), and electronic resistance (ρ_el). Fit data to transmission line models to quantify key parameters governing signal propagation [21].

Gate-Less Operation Testing: Characterize devices without gate bias to isolate contact-mediated dedoping effects. This confirms the role of asymmetric contacts in controlling channel doping distribution independent of conventional gating mechanisms [24].

Local Probe Techniques

Modulated Electrochemical Atomic Force Microscopy (MEC-AFM): Combine AFM with electrochemical control to map local ionic displacements with nanoscale resolution. Apply AC voltage signals while measuring tip response to quantify ion motion and accumulation at different frequencies [21]. This technique directly visualizes the spatial distribution of ionic activity correlated with electronic transport.

Optical Moving-Front Experiments: Use in situ spectroscopy to track doping front propagation through color changes in electrochromic OMIECs. Relate front velocity to applied potentials and extract ionic mobility and diffusivity values under operating conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful investigation of hole chemical potential and ion drift-diffusion requires specific materials and characterization tools. The following table outlines essential components for experimental research in this domain.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for OMIEC Transport Studies

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conducting Polymers | PEDOT:PSS, PANI, PPy | Forms OMIEC matrix for charge transport | Mixed ionic-electronic conduction, biocompatibility [21] [24] |

| Ionic Solutions | PBS, physiological buffers | Electrolyte environment for bioelectronic operation | Biologically relevant ions, concentration matching tissue |

| Characterization Tools | Modulated EC-AFM | Maps local ionic displacements | Combined electrochemical control, nanoscale resolution [21] |

| Device Fabrication | Asymmetric contact patterning | Creates complementary transistors from single material | Geometrical control of dedoping regions [24] |

| Internal Ion Reservoirs | Ion-gels, polymeric electrolytes | Enables fast ion access for MHz operation | Reduces ionic transit time [24] |

Applications in Biomaterials Research

Implantable Bioelectronic Devices

The interplay between hole chemical potential and ion drift-diffusion enables fully implantable organic electronic devices that directly interface with biological tissue. Complementary IGTs (cIGTs) created through asymmetric contact designs form high-performance conformable amplifiers with 200 V/V uniform gain and 2 MHz bandwidth [24]. These devices demonstrate long-term in vivo stability, maintaining functionality for over one month when implanted in freely moving rats. Their miniaturized biocompatible design allows implantation in developing rodents to monitor network maturation—an application previously impossible with conventional rigid electronics [24].

Neuromorphic Computing and Bio-Inspired Circuits

OMIECs exhibit natural suitability for neuromorphic computing applications that mimic biological information processing. The coupled ion-hole transport dynamics can replicate synaptic plasticity and neural signaling patterns with exceptional energy efficiency. Signal propagation in OMIEC channels follows cable equations mathematically analogous to those describing nerve pulse transmission along axons [21]. In both systems, charge transport undergoes dissipation caused by coupling with the surrounding medium, creating similar dispersion relations that can be exploited for bio-inspired computing architectures.

Biosensing and Signal Amplification

Organic electrochemical transistors leverage the hole-ion interplay for highly sensitive biosensing applications. The strong coupling between chemical potential changes and ionic redistribution enables amplification of weak physiological signals directly at the tissue-device interface, significantly improving signal-to-noise ratios for monitoring neural activity, biomarker detection, and physiological monitoring [24].

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant advances, several challenges remain in fully exploiting the interplay between hole chemical potential and ion drift-diffusion in OMIECs. Stability under physiological conditions, long-term performance retention, and precise control of material properties at nanoscale interfaces require further development. Future research directions include:

- Multiscale Modeling: Developing integrated models connecting molecular structure to device performance through more accurate representation of the hole-ion coupling.

- Advanced Characterization: Creating operando techniques to dynamically map both ionic and electronic distributions during device operation.

- Material Innovation: Designing new OMIEC architectures with decoupled pathways for ionic and electronic transport to minimize tradeoffs between speed and capacity.

- Biological Integration: Optimizing interface compatibility between OMIECs and living tissue for chronic implantation scenarios.

The continued refinement of our understanding of the fundamental charge transport physics governing hole chemical potential and ion drift-diffusion will enable increasingly sophisticated bioelectronic devices that seamlessly integrate with biological systems, ultimately transforming capabilities in medical diagnostics, neural interfaces, and personalized medicine.

The Critical Role of Polymer Sidechains and Backbone Chemistry in Governing Transport

The emergence of organic mixed ionic-electronic conductors (OMIECs) represents a significant advancement in biomaterials research, enabling innovative applications in bioelectronics, neuromorphic computing, and tissue engineering [3]. These conjugated polymeric materials possess the unique ability to transport both ions and electronic charge carriers (holes and electrons), making them ideally suited for interfacing biological systems that primarily communicate through ionic signals [3]. The dynamic interactions between polymer functionalities and electrolyte species fundamentally govern OMIEC performance, particularly in aqueous biological environments [3]. Understanding how molecular architecture dictates charge transport is therefore crucial for designing next-generation biomedical devices, including biosensors, neural interfaces, and conductive tissue scaffolds.

At the heart of OMIEC functionality lies the complex interplay between the conjugated backbone, which facilitates electronic transport, and the sidechain chemistry, which mediates ionic interactions [3] [25]. This review systematically examines the critical role of polymer sidechains and backbone chemistry in governing transport phenomena, with a specific focus on implications for biomaterials research. By integrating recent advances in operando characterization and computational modeling, we aim to establish clear structure-property relationships that can guide the rational design of OMIECs with optimized performance for biomedical applications.

Molecular Design Principles for Enhanced Transport

Sidechain Engineering Strategies

Sidechain engineering has emerged as a powerful strategy for precisely tuning OMIEC properties without altering the fundamental electronic structure of the conjugated backbone. The chemical composition, molecular structure, and spatial arrangement of sidechains significantly impact ion transport kinetics, hydration behavior, and microstructural organization in OMIECs [3].

Table 1: Sidechain Design Strategies and Their Impact on OMIEC Properties

| Sidechain Type | Key Characteristics | Impact on Ionic Transport | Impact on Electronic Transport | Biomedical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethylene Glycol (EG) | Polar, ion-coordinating oxygen atoms | Enhanced ion uptake and mobility | Potential degradation due to excessive swelling | Bio-compatibility; aqueous operation |

| Alkyl-Spacer Modified EG | EG units separated from backbone by alkyl segments | Balanced ion transport with reduced swelling | Maintained electronic pathways via controlled hydration | Improved operational stability in physiological environments |

| Ionic Functionalized | Zwitterionic or charged groups attached via spacers | Specific ion selectivity and transport | Modulated electrochemical doping efficiency | Enhanced biosensing specificity |

| Hybrid Designs | Combination of different sidechain types | Fine-tuned ion transport pathways | Optimized microstructural organization | Customizable for specific bio-interfaces |

The proximity of oxygen atoms to the polymer backbone in ethylene glycol-based sidechains profoundly influences ionic conductivity. Research demonstrates that direct attachment of oxygen atoms to the backbone versus through a methylene bridge creates measurable differences in ion transport capabilities [25]. Even subtle changes in oxygen atom placement within oligoethylene glycol sidechains can significantly alter polymer morphology and interactions with dissolved salts [25].

Advanced sidechain designs now incorporate zwitterionic groups or charged species attached via alkyl spacers to balance hydration, swelling, and transconductance [3]. These strategies aim to reduce excessive swelling while preserving efficient ion uptake and electronic charge carrier mobility when OMIECs are exposed to aqueous electrolytes similar to physiological environments [3].

Backbone Chemistry and Electronic Structure

While sidechains primarily mediate ionic transport, the conjugated backbone dictates electronic conduction through intrachain transport along the polymer backbone and interchain hopping between adjacent chains or conjugated segments [3]. The efficiency of electronic transport depends critically on backbone planarity, π-π interactions, and the presence of crystalline domains that facilitate charge delocalization [3].

Recent studies have revealed that certain donor-acceptor polymers like indacenodithiophene-co-benzothiadiazole (IDT-BT) can achieve extreme doping levels beyond conventional limits, accessing deeper energy bands (HOMO-1 derived bands) without degradation [26]. This exceptional stability enables operation in three distinct transport regimes, including a previously inaccessible Regime III where conductivity can exceed 30 S cm⁻¹ at doping concentrations surpassing two dopants per polymer repeat unit (n > 2) [26].

The coupling between electronic and ionic charge carriers manifests through polaron formation—where injected electronic charges become stabilized by nearby ions from the electrolyte [3]. In p-type accumulation mode materials, oxidation of the backbone (hole injection) accompanies anion injection into the polymer matrix when a doping potential is applied [3]. This electrochemical doping process directly modulates the concentration and mobility of electronic charge carriers, thereby governing the electronic conductivity of the material.

Advanced Characterization and Experimental Protocols

Operando Characterization Techniques

Elucidating the dynamic processes associated with ion uptake and ionic-electronic coupling under operational conditions requires advanced operando characterization techniques that capture real-time microstructural changes during device operation [3].

Operando Grazing-Incidence Wide-Angle X-ray Scattering (GIWAXS) provides insights into doping-induced structural transformations, including lamellar expansion, changes in π-π stacking distance, and crystallinity evolution [26]. For example, GIWAXS studies reveal that IDT-BT experiences only minor reversible increases in crystallinity upon doping, while polymers like PBTTT form highly ordered co-crystals with specific ion stoichiometries that limit further ion incorporation [26].

Electrochemical Quartz Crystal Microbalance with Dissipation Monitoring (EQCM-D) enables precise quantification of mass changes during electrochemical doping, allowing researchers to correlate ion injection with charge compensation processes and differentiate between various ionic species involved in the redox process [3].

In situ Scanning Probe Microscopy techniques capture nanoscale morphological evolution and ionic distribution within OMIEC thin films under applied potentials, revealing how microstructural changes impact both ion mobility and electronic transport [3].

Table 2: Key Experimental Techniques for Investigating OMIEC Transport Properties

| Technique | Key Measurements | Information Obtained | Protocol Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operando GIWAXS | Crystal structure, π-π stacking distance, lamellar spacing | Dynamic structural changes during electrochemical doping | Synchrotron source required; specialized electrochemical cells |

| EQCM-D | Mass changes, viscoelastic properties | Ion and solvent influx/efflux during doping | Requires piezoelectric sensors; careful calibration essential |

| X-ray Photoemission Spectroscopy | Elemental composition, chemical states | Dopant concentration and distribution | Ultra-high vacuum environment; surface-sensitive technique |

| Seebe Coefficient Measurements | Thermoelectric voltage | Density of states and charge carrier type | Temperature gradient control; simultaneous conductivity measurement |

| Double-Gating Experiments | Conductivity under non-equilibrium conditions | Ion-electron correlation and Coulomb gap formation | Dual-gate device fabrication; precise voltage sequencing |

Protocol for Investigating Sidechain-Dependent Swelling Behavior

To systematically evaluate how sidechain design influences hydration and swelling in aqueous environments, researchers can employ the following protocol:

Thin Film Preparation: Spin-coat OMIEC solutions onto patterned electrode substrates with precise control over thickness (typically 50-100 nm) and annealing conditions to ensure reproducible microstructure.

Electrochemical Doping: Utilize a three-electrode electrochemical cell with the OMIEC film as working electrode, Ag/AgCl reference electrode, and platinum counter electrode. Apply gate voltages ranging from 0 V to the oxidation potential in small increments (e.g., 0.1 V steps) in physiological buffer solutions (e.g., PBS at pH 7.4).

Simultaneous EQCM-D Measurement: Monitor frequency shifts (Δf) and dissipation changes (ΔD) corresponding to mass uptake and viscoelastic properties during doping. Calculate mass changes using the Sauerbrey equation for rigid films or more sophisticated models for hydrated systems.

Correlation with Electronic Performance: Simultaneously measure OECT characteristics (transfer curves, transconductance) to directly correlate swelling behavior with electronic transport properties.

Post-Operation Analysis: Characterize film morphology after operation using atomic force microscopy to assess irreversible structural changes or degradation.

This integrated approach reveals how sidechain modifications control the balance between ion uptake (necessary for ionic-electronic coupling) and excessive swelling (detrimental to electronic transport) [3].

Biomaterials Applications and Transport Considerations

The unique transport properties of OMIECs make them particularly valuable for bioelectronic applications where seamless integration with biological systems is essential. In neural tissue engineering, conductive polymers mimic the electrical properties of native neural tissues, promoting neuronal growth, differentiation, and repair [27]. Similarly, in cardiac tissue engineering, OMIECs support the electrical stimulation necessary for cardiomyocyte contraction and regeneration [27].

The electrophysiological simulation capability of conductive materials enables the creation of microenvironment resembling natural physiological conditions for neurons [28]. Conductive polymers like polypyrrole establish microcurrent environments within nerve conduits that enhance nerve cell development and axonal extension [28]. Electrical stimulation has been shown to improve early regeneration phases, including axonal sprouting and neuronal survival across various nerve injury models [28].

For OMIECs to function effectively in biomedical devices, they must maintain operational stability in aqueous environments while withstanding repeated electrochemical (de)doping cycles [3]. This necessitates sidechain designs that minimize excessive swelling—a common failure mechanism in ethylene glycol-based systems—while maintaining efficient ionic-electronic coupling [3]. Hybrid sidechain strategies that incorporate ionic moieties offer promising pathways to enhance material robustness without compromising mixed conduction properties [3].