In Vivo Photopolymerization for Bioelectronics: A New Paradigm for Minimally Invasive Neural Interfaces

This article explores the transformative potential of in vivo photopolymerization, a groundbreaking technique for creating soft, conductive bioelectronic interfaces directly within living tissue.

In Vivo Photopolymerization for Bioelectronics: A New Paradigm for Minimally Invasive Neural Interfaces

Abstract

This article explores the transformative potential of in vivo photopolymerization, a groundbreaking technique for creating soft, conductive bioelectronic interfaces directly within living tissue. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we cover the foundational principles of this technology, from novel photoactive monomers and light sources to the formation of biocompatible conductive hydrogels. The scope extends to detailed methodological approaches for creating complex 3D circuits in vivo, strategies for optimizing polymerization kinetics and overcoming oxygen inhibition, and a comparative analysis with traditional bioelectronics. By synthesizing the latest research, this review highlights how this minimally invasive approach can mitigate inflammatory responses and enable new therapeutic strategies for neurological diseases, marking a significant advancement in personalized bioelectronic medicine.

The Principles and Promise of In-Situ Bioelectronic Fabrication

Defining In Vivo Photopolymerization for Biomedical Applications

In vivo photopolymerization represents a transformative methodology in bioelectronics, enabling the direct formation of conductive polymer structures within living organisms. This process involves the spatial control of polymerization reactions using light, facilitated by photolithography masks, to create sophisticated electrode patterns and layered circuits in vivo [1]. Unlike pre-formed implanted electrodes, which often cause inflammation and scarring, in vivo photopolymerization allows for the creation of biocompatible, intricately patterned conductive structures that conform to biological tissues. This application note details the protocols, quantitative parameters, and material requirements for implementing this technology in biomedical research, particularly for the development of advanced bioelectronic therapeutics.

The core advantage of this technique lies in its combination of spatial control and biocompatibility. Traditional implanted electrodes, while offering good geometric control, are rigid and provoke a foreign body response. Conversely, earlier in situ methods, such as enzymatically catalyzed conductive polymer formation, suffer from slow kinetics governed by diffusion, with curing times spanning hours to days [1]. In vivo photopolymerization overcomes these limitations by using light to rapidly define conductive patterns with short curing times of 5-30 minutes, opening the possibility for creating complex 3D layer-on-layer circuits directly within biological environments [1].

The following tables consolidate key quantitative data essential for the planning and execution of in vivo photopolymerization experiments. These parameters directly influence the properties of the resulting conductive polymers and their compatibility with biological systems.

Table 1: Key Photopolymerization Process Parameters and Outcomes

| Parameter | Value / Range | Significance / Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Curing Time | 5 - 30 minutes | Significantly faster than enzymatic methods (hours/days); enables rapid device formation in vivo [1]. |

| Light Wavelength | Green and Red Light | Adapted for in vivo conditions to ensure tissue compatibility and sufficient penetration [1]. |

| Spatial Control | Defined by Photolithography Masks | Enables the creation of specific, layered patterns and complex 3D circuits, unlike basic electrode structures from other in situ methods [1]. |

| Conductive Polymer | Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)butoxy-1-sulfonate (PEDOT-S) derivative A5 | Results in conductive structures with desired electronic properties for bioelectronics [1]. |

| Key Monomer | 3Es (EDOT-trimers) | Novel photoactive monomers used alone or in mixture to cure the PEDOT-S derivative [1]. |

Table 2: Material Properties and Characterization Data

| Property / Condition | Measurement | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Shrinkage Strain | ~5% (after solidification) | Measured in acrylate resin model systems; strain variation became milder as the reaction proceeded [2]. |

| Young's Modulus | Increased nearly linearly with conversion degree (φ) | Characterized in thin films (0.05 mm) under constant light intensity (5 mW cm⁻²); relationship is linear before glass transition is passed [2]. |

| Bending Curvature | Decreased with illumination time and incident light intensity | Observed in polymer strips cured via FPP; curvature is dependent on the incident energy dose (irradiation time × intensity) [2]. |

| Light Intensity (FPP) | 5 mW cm⁻², 9.5 mW cm⁻² | Used in frontal photopolymerization experiments to study curing depth and bending behavior [2]. |

| UV Laser Power | 1.5 mW cm⁻² | Used for photopolymerization of liquid-crystalline monomers in visualization studies [3]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: In Vivo Photopolymerization of Conductive Patterns

This protocol describes the formation of detailed conducting polymer patterns within a living organism using photopolymerization, adapted from recent pioneering research [1].

I. Materials Preparation

- Monomer Solution: Prepare a solution of the 3Es (EDOT-trimers) photoactive monomers. This solution can be used alone or in a mixture formulated to cure the PEDOT-S derivative A5.

- Light Source: Set up a light source capable of emitting in the green and red spectra (e.g., lasers or LEDs), adapted for safe use in vivo.

- Photolithography Mask: Design and fabricate a mask with the desired electrode or circuit pattern. This mask will define the geometry of the polymerized structure.

II. Surgical Preparation and Administration

- Anesthetize the animal subject according to approved institutional animal care protocols.

- Perform a sterile surgical procedure to expose the target tissue or organ where the bioelectronic device is to be formed.

- Inject or apply the prepared monomer solution directly to the target site in vivo.

III. Photopolymerization Process

- Position the photolithography mask between the light source and the target area. The mask can be placed externally for superficial targets or, where feasible, miniaturized and introduced internally.

- Irradiate the target area with light for a duration of 5 to 30 minutes. The exact time depends on the light intensity, monomer formulation, and desired degree of polymerization.

- During irradiation, the photopolymerization reaction proceeds selectively in the illuminated areas defined by the mask, forming a solid, conductive polymer structure.

IV. Post-Polymerization and Analysis

- After irradiation, carefully close the surgical site if applicable.

- Monitor the subject and allow for recovery.

- The resulting conductive structure can be characterized ex vivo at the endpoint for its electrical properties, integration with tissue, and lack of adverse immune responses.

Protocol: Frontal Photopolymerization (FPP) for Origami Structures

This protocol utilizes FPP to create three-dimensional origami structures based on photopolymerization-induced volume shrinkage, a mechanism relevant to forming compliant bioelectronic interfaces [2].

I. Resin and Substrate Preparation

- Resin Formulation: Prepare a photocurable polymer resin (e.g., acrylate-based). To control light penetration, add a photoabsorber to the resin to create an attenuated light field.

- Substrate Treatment: Use a Poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) substrate placed in a petri dish. PDMS provides an anti-stiction surface, ensuring the cured part can be easily removed, which is crucial for the bending behavior.

II. Photopolymerization and Shape Formation

- Fill the PDMS-lined petri dish with the liquid resin.

- Project light upward from the bottom of the dish through the transparent substrate. The light intensity (e.g., 5 mW cm⁻²) and irradiation time are critical control parameters.

- Due to the photoabsorber, a light intensity gradient is created, leading to non-uniform curing and volume shrinkage through the thickness of the resin. The layer directly exposed to light cures faster than subsequent layers.

- This sequential shrinkage creates a non-uniform stress field: the early-cured layer (near the substrate) develops compressive stress, while the newly-cured layer develops tensile stress.

III. Release and 3D Structure Formation

- Remove the solidified film from the PDMS substrate. Upon release, the internal stress gradient is relieved, causing the sample to bend toward the newly cured side.

- The bending curvature can be precisely controlled by adjusting the irradiation dose (time × intensity). Higher doses generally result in thicker, stiffer films with lower curvature.

- By spatially controlling the curing conditions (e.g., using grayscale patterns), complex 3D origami structures can be created spontaneously upon release from the substrate.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for In Vivo Photopolymerization Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function and Application in Research |

|---|---|

| 3Es (EDOT-trimers) | Novel photoactive monomers that, upon light exposure, form the backbone of the conductive polymer network, either alone or in a mixture with PEDOT-S [1]. |

| PEDOT-S Derivative A5 | A specific conductive polymer derivative that is cured during the photopolymerization process, resulting in structures with enhanced electronic properties for biointerfacing [1]. |

| Photoabsorbers | Added to the resin to create an attenuated light field, which is essential for generating the curing gradient in frontal photopolymerization that drives bending and 3D structure formation [2]. |

| PDMS (Polydimethylsiloxane) Substrate | Used as a non-adhesive substrate during FPP. Its anti-stiction properties, due to residual oxygen inhibition and pendent oligomers, allow the cured polymer to detach and bend freely [2]. |

| Quantum Dots (e.g., CdSe/ZnS) | Used as fluorescent tracers at minute concentrations to visualize mass flow and diffusion processes during photopolymerization via single-particle fluorescence imaging [3]. |

| Photolithography Masks | Critical for defining the spatial pattern of the polymerized structure. The mask blocks light in specific areas, allowing for the creation of detailed electrodes and circuits [1]. |

Workflow and Signaling Visualizations

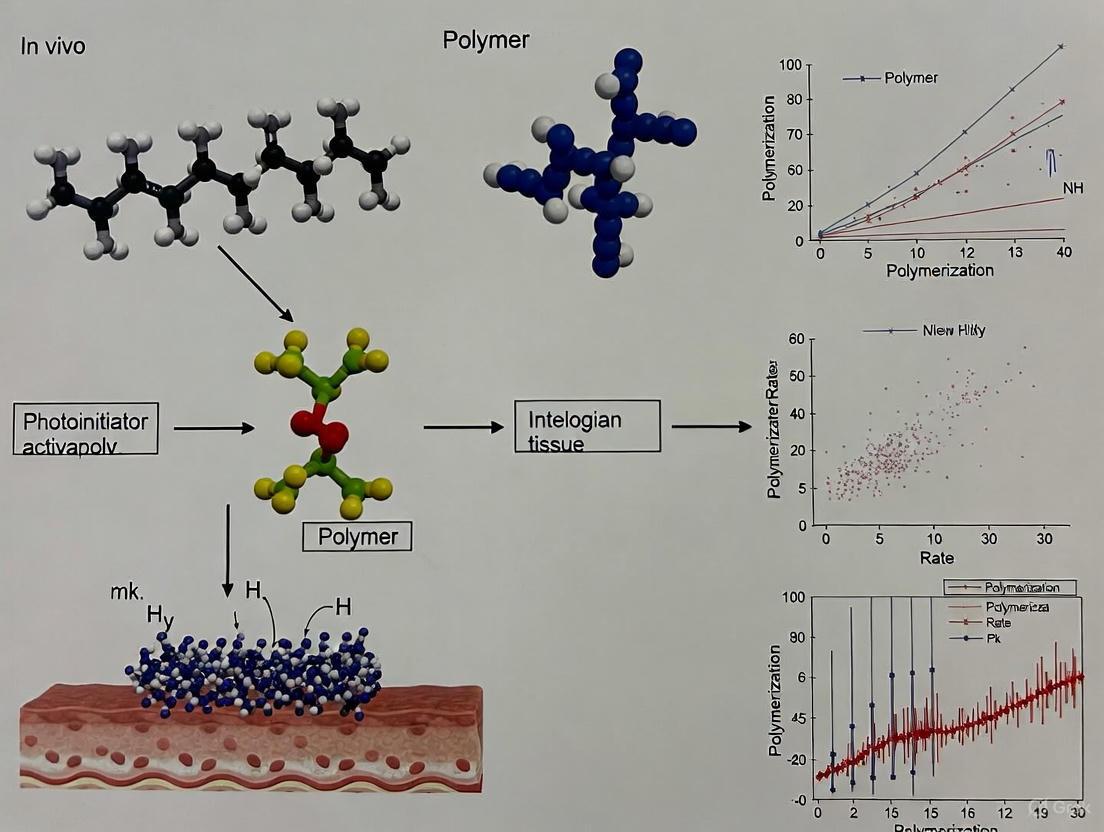

In Vivo Photopolymerization Workflow

Mass Flow Induced Alignment

Photopolymerization, a process where light transforms liquid monomers into solid polymers, is revolutionizing the fabrication of bioelectronic devices [4]. This technique provides unparalleled spatial and temporal control, enabling the creation of sophisticated, tissue-conformal electronics directly within biological environments [5]. The core components of this technology—photoactive monomers, photoinitiators, and light sources—determine the success of in vivo applications, influencing everything from biocompatibility and electrical conductivity to the resolution of the final construct. Within the context of bioelectronics, these components must be carefully engineered to function under physiological conditions, minimize immune response, and integrate seamlessly with soft, dynamic tissues [4]. The shift toward in vivo photopolymerization represents a paradigm change from traditional pre-fabricated, rigid implants to soft, compliant devices formed directly at the site of implantation.

Core Components and Material Selection

Photoactive Monomers

Photoactive monomers are the fundamental building blocks that form the polymer network upon light exposure. For in vivo bioelectronics, these monomers must meet stringent requirements for biocompatibility, mechanical matching with tissues, and often, biodegradability.

Acrylic Monomers are widely used due to their high reactivity. In the context of bioelectronics, formulations often include:

- Acrylamide (AAm): Serves as a primary monomer for forming hydrogel networks that can host conductive materials [6].

- 2-Hydroxyethyl Acrylate (HEA): Provides hydrophilic character and improves biocompatibility [6].

- Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Diacrylate (PEGDA): Acts as a crosslinker to control hydrogel mesh size and mechanical properties [6].

- 2-Hydroxyethyl Methacrylate (HEMA): A common reactive diluent in urethane acrylate-based systems [7].

Biodegradable Elastomers are engineered for transient electronics. A prominent example is acrylated Poly(L-lactide-co-ε-caprolactone) (UV-PLCL), which combines the elasticity of caprolactone with the biodegradability of lactide. Under light exposure, the acrylic end-groups facilitate cross-linking to form a soft, degradable network ideal for temporary implants [5].

Photoinitiators (PIS) and Photosensitizers (PS)

Photoinitiators are compounds that absorb light and generate active species (free radicals) to start the polymerization reaction. Their selection is critical for deep tissue curing and biocompatibility.

Conjugated Polymer Nanoparticles, such as Poly(3-hexylthiophene) Semiconducting Polymer Nanoparticles (P3HT SPNs), represent a major advancement [6]. They function with a dual role:

- As Visible-Light Photoinitiators: P3HT SPNs absorb visible light (e.g., λ = 467 nm) to generate free radicals, enabling the polymerization of acrylic hydrogels without requiring toxic co-initiators [6].

- As Photosensitizers: Once embedded within the polymerized hydrogel, P3HT SPNs retain their photoelectrochemical properties. Upon subsequent light exposure, they generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as 12-15 μM H₂O₂, enabling applications in photodynamic therapy [6].

Traditional Photoinitiating Systems are often used in bimolecular configurations:

- Dye Sensitizers: Camphorquinone (CQ) and Eosin Y (EY) absorb specific light wavelengths.

- Co-initiators: These include iodonium salts (e.g., diphenyliodonium hexafluorophosphate), thiols (e.g., trimethylolpropane tris(3-mercaptopropionate)), and amines (e.g., triethylamine). The co-initiator reacts with the excited dye to produce the initiating radicals [7] [5].

- Type I Photoinitiators: Such as ethyl (2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl) phenylphosphinate (TPO-L) and 2,4,6-Trimethylbenzoyldiphenylphosphine oxide (TPO), undergo cleavage upon light absorption to directly generate free radicals [7] [5].

Table 1: Key Photoinitiator Systems for Biomedical Applications

| Photoinitiator / System | Activation Wavelength | Co-initiator Required? | Key Characteristics | Demonstrated Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P3HT SPNs [6] | Visible light (λ > 405 nm, e.g., 467 nm) | No | Dual role as PI and PS; High biocompatibility | In vitro hydrogel PDT against cancer cells |

| Camphorquinone (CQ) System [7] | 365 nm & 405 nm (Dual LED) | Yes (e.g., Iodonium salts, amines) | Common in dental and cosmetic applications | Highly pigmented UV/LED-curable nail gels |

| Eosin Y (EY) System [7] | 365 nm & 405 nm (Dual LED) | Yes (e.g., Iodonium salts, thiols) | Highly pigmented UV/LED-curable nail gels | |

| TPO / TPO-L [7] [5] | 365 nm | No (Type I) | Efficient radical generation via cleavage | Pigmented coatings; Biodegradable elastomers |

The choice of light source dictates the penetration depth, curing speed, and viability of surrounding tissues.

- Wavelength: Blue (467 nm), green, and red light are used for in vivo processes due to their superior tissue penetration compared to UV light [4]. UV (365 nm) and violet (405 nm) are common in dual-LED systems for surface curing and in vitro applications [7].

- Source Type: LED lamps are prevalent due to their narrow emission spectra, low heat output, and portability. Systems can be configured with single or multiple wavelengths (e.g., dual 365/405 nm LEDs) to activate different initiators simultaneously [7].

- Intensity and Dose: Controlled intensity (e.g., 0.5 to 5.0 W/cm²) and exposure time (seconds to minutes) are critical parameters that directly influence the polymerization rate, final conversion, and mechanical properties of the material [8].

Application Notes: In Vivo and In Vitro Protocols

Protocol 1: In Vivo Formation of Conductive Bioelectrodes

This protocol details the direct formation of soft, conductive hydrogels within living tissue for neural interfacing, based on the work by researchers at Lund University [4].

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- Light-sensitive ink: A solution of light-sensitive monomers (e.g., acetylene-functionalized conductive precursors) and a photoinitiator in a biocompatible buffer.

- Light source: LED lamp with adjustable wavelength (blue, green, or red) and intensity.

- Delivery system: Sterile syringe with a fine-gauge needle for minimally invasive injection.

- Animal model (e.g., zebrafish, chicken embryo, or mammalian model).

Procedure:

- Ink Preparation: Formulate the light-sensitive ink under sterile conditions. The viscosity should be suitable for injection.

- Ink Injection: Using a surgical procedure, carefully inject a small volume (scale-dependent on the target organism) of the ink into the target tissue, such as the brain or heart.

- Light Exposure: Within minutes of injection, expose the injection site to the selected light wavelength. For deep tissues, longer wavelengths (e.g., red) are preferred.

- Polymerization: Maintain light exposure for 5 to 30 minutes. The rapid reaction forms a soft, conductive hydrogel (with conductivity up to 10 S/m) that integrates with the host's cells and extracellular matrix.

- Validation: The resulting bioelectrode can be used immediately for applications such as regulating neural electrical signals. The device degrades naturally after use, requiring no surgical removal.

Protocol 2: Fabrication of P3HT-Based Hydrogels for Photodynamic Therapy

This protocol describes using P3HT SPNs as a dual-purpose visible-light photoinitiator and photosensitizer to create functional hydrogels for cancer therapy [6].

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- Monomer solution: Aqueous solution of acrylic monomers (e.g., Acrylamide (AAm), 2-Hydroxyethyl Acrylate (HEA), and crosslinker Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Diacrylate (PEGDA)).

- P3HT SPNs suspension: Semiconducting polymer nanoparticles in water at a known concentration.

- Light source: Lamp emitting visible light at 467 nm.

- Photo-rheometer: For monitoring the gelation process in real-time.

- Cell culture materials: GL261 cancer cells or S. aureus bacteria for efficacy testing.

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Mix the monomer solution. For a PEGDA hydrogel, add the P3HT SPNs suspension to achieve a final concentration between 5 and 105 mg/mL. Higher concentrations (e.g., 80 mg/mL) lead to faster gelation.

- Gelation Monitoring: Transfer the solution to a photo-rheometer. Expose to 467 nm light and monitor the shear storage (G') and loss (G") moduli. The gelation point is identified when G' equals G". At 80 mg/mL P3HT SPNs, this typically occurs in ~45 minutes [6].

- Hydrogel Formation: Continue illumination until a solid hydrogel is formed. The resulting P3HT-loaded hydrogel is dark-colored and consistent.

- Photodynamic Therapy Application: Place the hydrogel in contact with target cells (e.g., GL261 glioma cells) under physiological conditions. For therapy, illuminate the hydrogel a second time with 467 nm light. This stimulates the embedded P3HT SPNs to generate ROS, leading to a ~50% reduction in cancer cell viability and ~99% death of S. aureus bacteria [6].

Protocol 3: Monolithic 3D Fabrication of Soft, Transient Electronics

This protocol outlines a layer-by-layer method for creating sophisticated, biodegradable electronic devices using solution-casting and photopatterning [5].

Materials:

- Substrate/Insulator: UV-PLCL resin with TPO (photoinitiator) and TTMP (crosslinking enhancer).

- Semiconductor: PLCL polymer matrix with P3HT nanofibrils and a diazirine crosslinker.

- Conductor: PEDOT:PSS solution with 2,4-hexadiyne-1,6-diol (HDD) and Zonyl FS-300 (surfactant).

- Fabrication setup: Spin coater, 365 nm and 254 nm UV light sources, and developing baths.

Procedure:

- Substrate Patterning: Spin-coat the UV-PLCL resin onto a carrier. Expose through a photomask to 365 nm UV light to crosslink and define the substrate pattern. Develop to remove unexposed resin.

- Semiconductor Deposition: Spin-coat the P3HT/PLCL semiconducting solution onto the substrate. Expose to 365 nm UV light without a mask to crosslink the entire layer via the diazirine crosslinker, forming a robust semiconducting film.

- Conductor Patterning: Spin-coat the PEDOT:PSS/HDD conducting solution. Expose through a photomask to 254 nm UV light to initiate the topochemical polymerization of HDD, which crosslinks and renders the exposed pattern insoluble. Develop with deionized water to remove unexposed areas.

- Post-processing: Enhance the conductivity of the PEDOT:PSS traces by secondary doping in methanol or 40% H₂SO₄.

- Application: This process can be repeated to build multilayer structures, resulting in integrated devices such as transistor arrays, sensors, and electrodes on an ultrathin (~3 μm), soft, and biodegradable platform.

Table 2: Quantitative Data from Photopolymerization Research

| Experiment / System | Key Parameter Measured | Result / Value | Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| P3HT SPN Gelation [6] | Gelation Time | ~45 min (80 mg/mL SPNs) ~65 min (105 mg/mL SPNs) ~80 min (5 mg/mL SPNs) | Monomers: AAm, HEA, PEGDA Light: λ = 467 nm |

| P3HT SPN Photocurrent [6] | Photocurrent Density | ~0.2 to ~1.1 μA cm⁻² | Embedded in hydrogel; Light: λ = 467 nm |

| P3HT SPN ROS Generation [6] | H₂O₂ Production | 12 - 15 μM | Upon illumination (λ = 467 nm) |

| Scaffold Fabrication (PCLTA) [8] | Light Intensity | 0.5 - 5.0 W/cm² | Polymer: PCLTA, Photoinitiator: Irgacure 2959 |

| Scaffold Fabrication (PCLTA) [8] | Exposure Time | 125 - 350 s | Varies with light intensity |

| Conductor Patterning (PEDOT:PSS) [5] | Optimal HDD Concentration | ~10% (w/w) | For effective photopatterning |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for In Vivo Photopolymerization Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Role | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| P3HT SPNs [6] | Visible-light Photoinitiator & Photosensitizer | Enables hydrogel formation and ROS generation without co-initiators. |

| UV-PLCL [5] | Biodegradable Substrate/Insulator | Acrylated Poly(L-lactide-co-ε-caprolactone); forms soft, elastic, and degradable films. |

| PEDOT:PSS with HDD [5] | Photopatternable Conductor | HDD crosslinks under 254 nm light, allowing for high-resolution aqueous patterning. |

| Diazirine Crosslinker [5] | Semiconductor Crosslinker | Forms stretchable semiconducting network with P3HT/PLCL upon 365 nm exposure. |

| TPO / TPO-L [7] [5] | Type I Photoinitiator | Efficient for UV curing (365 nm) in thick or pigmented systems and elastomers. |

| Iodonium Salts [7] | Co-initiator | Works with dye sensitizers (CQ, Eosin Y) in bimolecular photoinitiating systems. |

| Thiol Additives (e.g., TTMP) [5] | Crosslinking Enhancer | Mitigates oxygen inhibition, enabling efficient polymerization in ambient conditions. |

| Dual-Wavelength LED Lamp [7] | Light Source | Simultaneous 365 nm & 405 nm output for activating multiple photoinitiators. |

The integration of bioelectronic devices with biological tissues presents a significant challenge in modern therapeutic development. Conventional implanted electronics, typically composed of rigid, substrate-bound materials like silicon and metals, often provoke adverse biological responses—including inflammation, fibrosis, and scar tissue formation—that compromise device functionality and long-term stability [9] [1]. These issues primarily stem from a fundamental mechanical mismatch between the rigid, planar electronics and the dynamic, soft nature of biological tissues. Consequently, there is a pressing need for innovative approaches that enhance both biocompatibility and mechanical congruence to enable seamless biointegration.

In vivo photopolymerization has emerged as a transformative methodology for creating conductive polymer structures directly within living organisms. This technique enables the fabrication of soft, compliant bioelectronic interfaces that conform to tissue structures, thereby minimizing mechanical stress and improving functional integration [9] [1]. This application note details the comparative advantages, experimental protocols, and material considerations for utilizing in vivo photopolymerization to overcome the limitations of traditional bioelectronic implants, with specific focus on applications in neural interfacing and cardiac monitoring.

Comparative Analysis: Traditional vs. Photopolymerized Bioelectronics

The table below summarizes the key differences between traditional implanted electronics and devices formed via in vivo photopolymerization, highlighting critical aspects of biocompatibility and mechanical matching.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Traditional vs. Photopolymerized Bioelectronic Implants

| Characteristic | Traditional Bioelectronics | In Vivo Photopolymerized Bioelectronics |

|---|---|---|

| Material Composition | Rigid substrates (e.g., silicon, metals) [9] | Soft, organic materials (e.g., PEDOT-S, UV-PLCL) [9] [1] |

| Biocompatibility & Tissue Response | Often trigger inflammation, fibrosis, and scarring [9] [1] | High biocompatibility; reduced foreign body response [9] [1] |

| Mechanical Properties | Rigid, non-compliant; significant mechanical mismatch with tissues [9] | Soft, stretchable, and elastic; conforms to tissue surfaces [9] |

| Fabrication & Integration | Pre-fabricated, implanted surgically; limited conformability [1] | Formed in situ via photopolymerization; enables seamless, conformal integration [9] [1] |

| Structural Complexity | Excellent control over 2D electrode geometry [1] | Enables complex 3D, layered patterns and circuits in vivo [1] |

| Curing/Formation Time | Not applicable (pre-formed) | Short curing times (5–30 minutes) [1] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: In Vivo Photopolymerization of Conductive Patterns

This protocol describes the methodology for forming detailed, biocompatible conductive patterns within a living organism using photopolymerization, as adapted from recent research [1].

Objective: To create spatially controlled, conductive polymer electrodes in vivo for bioelectronic interfacing.

Materials & Reagents:

- Photoactive Monomer: 3Es (EDOT-trimers) and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)butoxy-1-sulfonate (PEDOT-S) derivative A5.

- Light Source: Green (≈525 nm) or red (≈625 nm) light, selected for deeper tissue penetration and reduced phototoxicity.

- Photolithography Mask: A physical mask defining the desired 2D electrode pattern.

- Delivery System: A minimally invasive system for introducing the liquid monomer solution to the target site in vivo.

Procedure:

- Monomer Preparation: Prepare a solution of the 3Es and A5 monomers. The mixture is designed to remain stable until photoinitiated.

- Site Preparation: Perform a standard surgical procedure to expose the target tissue (e.g., brain cortex or cardiac muscle).

- Monomer Application: Apply the liquid monomer solution directly onto the target tissue surface.

- Mask Alignment: Carefully position the photolithography mask above the target area. The mask defines the geometry of the conductive pattern to be formed.

- In Vivo Photopolymerization: Expose the masked area to the green or red light source for a duration of 5 to 30 minutes. The light passes through the transparent regions of the mask, initiating a rapid polymerization reaction that solidifies the monomer into a conductive polymer (PEDOT-S) in the predefined pattern.

- Post-Processing & Validation: Gently rinse the area with a sterile physiological buffer to remove any unreacted monomer solution. The newly formed conductive pattern is now integrated with the tissue and ready for functional electrophysiological recording or stimulation.

Protocol: Fabrication of Multilayer, Transient Bioelectronic Sensors

This protocol outlines the steps for creating sophisticated, soft, and transient electronic devices using a layer-by-layer solution casting and photopatterning approach, as demonstrated for diagnostic and therapeutic applications [9].

Objective: To fabricate a multifunctional, biodegradable bioelectronic device for temporary spatiotemporal monitoring.

Materials & Reagents:

- Substrate/Insulator: UV-PLCL (Poly(l-lactide-co-ε-caprolactone) diol conjugated with acrylic acids).

- Semiconductor: A composite of PLCL polymer matrix and poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT) nanofibrils with a diazirine crosslinker.

- Conductor: A solution of PEDOT:PSS, 2,4-hexadiyne-1,6-diol (HDD), and Zonyl FS-300 surfactant.

- Photoinitiators: TPO (2,4,6-Trimethylbenzoyldiphenylphosphine oxide) and TTMP (Trimethylolpropane tris(3-mercaptopropionate)).

Procedure:

- Fabricate the Biodegradable Substrate:

- Prepare a solution of UV-PLCL, TPO, and TTMP.

- Solution-cast the mixture and expose to 365 nm wavelength light to crosslink the monomer into an elastic, biodegradable substrate layer.

Pattern the Semiconducting Layer:

- Apply the P3HT/PLCL composite solution onto the substrate.

- Use a mask to define semiconductor patterns and expose to 365 nm light. The diazirine crosslinker forms a robust, stretchable semiconducting network.

Form the Conductive Traces:

- Apply the PEDOT:PSS/HDD conductor solution.

- Use a mask and expose to 254 nm UV light. This triggers the topochemical polymerization of HDD, creating polydiacetylene and transforming PEDOT into a highly conductive, water-resistant pattern.

- Optional: Enhance conductivity by secondary doping via immersion in methanol or 40% H₂SO₄ for 3 minutes, increasing conductivity to ~2000 S/cm [9].

Layer Integration: Repeat the solution-casting and photopatterning steps to build additional functional layers (e.g., sensors, capacitors, microheaters) in a monolithic 3D structure.

Implantation and Function:

- The ultrathin (≈3 μm) and soft device can be implanted for applications like neural recording or cardiac pacing.

- The device operates for a designed lifespan before harmlessly dissolving via hydrolysis of the PLCL ester bonds, typically over several weeks [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table catalogues the key materials required for developing and applying in vivo photopolymerized bioelectronics.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for In Vivo Photopolymerization

| Material/Reagent | Function/Description | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| PEDOT-S / 3Es Monomers [1] | Photoactive precursors that form conductive polymer patterns (PEDOT) in vivo. | Polymerize under green/red light; form biocompatible conductors. |

| UV-PLCL [9] | A photopolymerizable, biodegradable elastomer used as substrate and insulator. | Soft, elastic; degrades via hydrolysis; excellent mechanical match for soft tissues. |

| P3HT Nanofibrils [9] | A semiconducting material used to create stretchable electronic components. | High carrier mobility; can be crosslinked into a PLCL matrix for durability. |

| PEDOT:PSS with HDD [9] | A conductor formulation that becomes patternable and water-resistant upon UV exposure. | HDD crosslinks into polydiacetylene under 254 nm light; enables high-conductivity traces. |

| TPO & TTMP [9] | Photoinitiator and crosslinking enhancer for the UV-PLCL substrate. | Enables free radical polymerization of UV-PLCL under 365 nm light in ambient conditions. |

| Diazirine Crosslinker [9] | Crosslinking agent for the P3HT/PLCL semiconductor composite. | Forms carbene under 365 nm light, creating strong C-H insertions for a robust network. |

Workflow and Signaling Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key advantages of creating bioelectronic interfaces via in vivo photopolymerization compared to the traditional implant approach.

The development of soft, biocompatible electronics is crucial for advanced medical applications, including precise neural interfaces, implantable sensors, and targeted therapeutic devices. Traditional rigid implants often provoke inflammatory responses and fibrotic scarring, leading to a loss of function over time. In vivo photopolymerization has emerged as a transformative methodology, enabling the direct formation of conductive hydrogels within living tissue. This protocol outlines the process of creating patterned conductive structures in situ using light, a technique that provides superior spatial control over electrode geometry compared to other in situ methods while maintaining excellent biocompatibility. The process involves the photopolymerization of novel photoactive monomers into conductive polymers such as poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) derivatives, defined by photolithography masks, to form complex, layered circuits directly within a biological environment [1] [10].

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the essential materials required for the in vivo photopolymerization process.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Materials for In Vivo Photopolymerization

| Item Name | Function/Description | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| 3E Monomers (e.g., 3E-S, 3E-COONa) [10] | Photoactive EDOT-trimer precursors that form the conductive polymer backbone. | Lower oxidation potential than ETE derivatives; water-soluble sulfonate or carboxylate groups for biocompatibility. |

| PEDOT-S Variant (A5) [10] | A pre-formed conductive polymer nanoparticle that forms a temporary ion-absorbing hydrogel in vivo. | Serves as a scaffold; photopolymerizing 3Es within it enhances pattern stability. |

| Rose Bengal [10] | A photocatalyst for polymerization under visible (green) light. | Enables polymerization with green light (550 nm); follows a single-electron transfer (SET) mechanism. |

| SIR-COOH [10] | A far-red absorbing photocatalyst. | Allows polymerization with red light (621 nm) for deeper tissue penetration. |

| Photolithography Masks [1] [10] | High-precision masks that define the spatial pattern of light exposure. | Enables the creation of detailed and specific 2D and 3D conductive patterns in vivo. |

| Alginate-based Hydrogels [11] | A biocompatible polymer matrix for creating injectable conductive composites. | Can be ionically cross-linked; provides a soft, tissue-matching environment for electronics. |

| PEDOT:AlgS [11] | A conductive polymer with alginate as a hydrophilic dopant instead of PSS. | Enhances water dispersibility and biodegradability; boosts hydrogel conductivity. |

Monomer and Polymer Properties

The selection of monomers is critical for successful photopolymerization under biologically relevant conditions. The 3E monomer family was specifically designed for this purpose, offering lower oxidation potentials and improved compatibility with aqueous systems compared to earlier derivatives [10].

Table 2: Characteristics of 3E Monomer Derivatives

| Monomer | Oxidation Potential (V vs. Ag/AgCl) | Key Functional Group | Light Source & Catalyst |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3E-S | 0.47 | Sulfonate | Green Light (550 nm) / Rose Bengal |

| 3E-COONa | 0.10 | Carboxylate | Far-UV (385 nm) or Red Light (621 nm) / SIR-COOH |

| 3E-PC | 0.05 | Phosphorylcholine | Not Specified |

Experimental Protocols

Workflow for In Vivo Photopolymerization

The following diagram illustrates the core experimental workflow for forming a patterned conductive hydrogel within a biological tissue.

Protocol 1: Pre-forming the Transient A5 Hydrogel Scaffold

- Solution Preparation: Prepare an aqueous solution of the PEDOT-S variant A5. This solution consists of nanoparticles that will self-assemble into a temporary conductive hydrogel upon injection.

- In Vivo Injection: Using a standard syringe or catheter, inject the A5 solution into the target tissue site in the animal model (e.g., zebrafish or chicken embryo).

- Scaffold Formation: The A5 nanoparticles will rapidly absorb ions from the surrounding biological tissue, leading to aggregation and the formation of a transient, conductive hydrogel scaffold. This scaffold temporarily occupies the space where the permanent pattern will be formed [10].

Protocol 2: Photopolymerizing 3E Monomers for Patterned Electrodes

- Ink Formulation: Prepare the photopolymerizable ink. This involves dissolving the chosen 3E monomer (e.g., 3E-COONa at 0.4 mg mL⁻¹) in a biocompatible buffer. Add the appropriate photocatalyst:

- Ink Injection and Mask Alignment: Inject the ink into the same site as the pre-formed A5 hydrogel. Carefully align a photolithography mask directly above or on the tissue surface. The mask contains the negative of the desired conductive pattern (e.g., lines, electrodes, or complex circuits) [1] [10].

- Light Exposure and Polymerization: Expose the masked area to the corresponding light source.

- Green Light: 550 nm wavelength at an intensity of 65 mW cm⁻² for 5 minutes.

- Red Light: 621 nm wavelength for up to 15 minutes. The light penetrates the tissue and passes through the transparent regions of the mask, initiating the photocatalytic reaction only in the exposed areas.

- Reaction Mechanism: The photocatalyst absorbs light and enters an excited state, triggering a Single-Electron Transfer (SET) mechanism. This process consumes oxygen and generates hydrogen peroxide in situ, which acts as an oxidant. The 3E monomers are polymerized into conjugated, conductive polythiophene chains within the A5 hydrogel matrix [10].

- Pattern Formation and Stabilization: After the light exposure, the unreacted monomer solution in the masked areas can be gently flushed away. The result is a stable, patterned conductive hydrogel integrated with the native tissue, with geometry defined by the photomask.

Performance Metrics and Characterization

The resulting conductive hydrogels can be characterized using the following key performance metrics, which demonstrate the efficacy of this approach.

Table 3: Performance Metrics of Photopolymerized Conductive Hydrogels

| Parameter | Typical Result/Value | Method of Analysis / Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Curing Time | 5 - 30 minutes [1] [10] | Dictates practical feasibility for in vivo procedures. |

| Light Wavelength | Green (550 nm) or Red (621 nm) [10] | Determines tissue penetration depth and biocompatibility. |

| Spatial Control | Specific, layered, and complex 3D patterns [1] | Enabled by photolithography masks; superior to diffusion-controlled methods. |

| Conductivity Enhancement | 20-fold increase in conductivity vs. conventional methods [11] | Achieved via hydrophilic dopants (e.g., PEDOT:AlgS); critical for device performance. |

| Dispersibility | 5-fold increase in aqueous dispersibility [11] | Allows for higher conductive filler loading in hydrogels. |

| Biocompatibility | Confirmed in zebrafish and chicken embryo models [10] | Essential for all in vivo applications. |

The Photopolymerization Mechanism

The chemical transformation from liquid monomer to solid conductive polymer is governed by a photocatalytic cycle. The following diagram details the Single-Electron Transfer (SET) mechanism, which is central to the reaction's success in an aqueous, biological environment.

Mechanism Explanation: The process begins when the photocatalyst (e.g., Rose Bengal or SIR-COOH) absorbs a photon of light and transitions to an excited state. This excited photocatalyst then interacts with dissolved oxygen, leading to the formation of hydrogen peroxide within the reaction zone. The generated hydrogen peroxide acts as a mild oxidant, which removes an electron from the 3E monomer to form a radical cation. This radical cation is highly reactive and initiates the chain propagation step, whereby it couples with other monomer units and radical cations, ultimately forming the long-chain, conjugated conductive polymer (e.g., PEDOT-S) that constitutes the final solid hydrogel [10]. This SET mechanism is crucial as it allows the use of benign visible light and generates reactants in situ, making it compatible with living tissues.

The development of in vivo-formed bioelectronics represents a paradigm shift for neural interfaces and therapeutic applications, aiming to overcome the mechanical mismatch and foreign body response associated with conventional pre-fabricated, rigid implants [12]. In vivo photopolymerization has emerged as a transformative approach for creating precisely patterned, soft conductive structures directly within living tissue [1] [4]. This methodology enables the formation of bioelectronic devices that integrate seamlessly with biological systems, offering unprecedented compatibility and minimal invasiveness.

Central to this technological advancement are two key material systems: PEDOT-S derivatives and novel 3E monomers (EDOT-based trimers) [10]. These conjugated molecules can be photopolymerized using biocompatible light sources to form conductive hydrogels and patterned electrodes in situ. Unlike enzymatically catalyzed conductive polymers which require hours to days for formation and offer limited spatial control, photopolymerization enables precise patterning within 5-30 minutes using visible light [1]. This breakthrough allows researchers to create complex, multi-layered circuits directly in vivo, opening new possibilities for interfacing with biological systems.

Material Properties and System Components

3E Monomers (EDOT-Trimers)

The 3E monomer family comprises sulfonated EDOT-based trimers specifically engineered for photopolymerization under physiological conditions. These molecules feature a lower oxidation potential compared to earlier EDOT derivatives, facilitating rapid polymerization with minimal energy input [10].

- 3E-S (EDOT-EDOT(S)-EDOT): The sulfonate-substituted core structure with oxidation potential of 0.47 V [10].

- 3E-COONa: Carboxylate variant with oxidation potential of 0.10 V versus Ag/AgCl [10].

- 3E-PC: Phosphorylcholine derivative with exceptionally low oxidation potential of 0.05 V versus Ag/AgCl [10].

The molecular design of 3E monomers incorporates hydrophilic substituents that enhance water solubility and biointegration while maintaining the conjugated backbone necessary for electrical conductivity after polymerization.

PEDOT-S Derivative A5

The PEDOT-S variant known as A5 (poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)butoxy-1-sulfonate) serves as a complementary component that forms conductive nanoparticles in aqueous solutions [10]. When introduced into biological environments, A5 nanoparticles spontaneously aggregate into temporary conductive hydrogels through absorption of ions from the surrounding tissue. This property enables the initial formation of a conductive matrix that can be subsequently stabilized and patterned through photopolymerization with 3E monomers.

Photocatalyst Systems

- Rose Bengal: Xanthene-based photocatalyst activated by green light (550 nm, 65 mW cm⁻²) with typical loading of 1-4% relative to monomer [10].

- SIR-COOH: Silicon-rhodamine analog excitable by red light (621 nm), enabling deeper tissue penetration and operating within the therapeutic optical window (600-1300 nm) [10].

Table 1: Key Material Components for In Vivo Photopolymerization

| Component | Chemical Classification | Key Properties | Role in Photopolymerization |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3E-S | Sulfonated EDOT trimer | Oxidation potential: 0.47 V; Water-soluble | Primary monomer forming conductive polymer backbone |

| 3E-COONa | Carboxylated EDOT trimer | Oxidation potential: 0.10 V; Enhanced biocompatibility | Functional monomer for tuned material properties |

| A5 | PEDOT-S derivative | Forms nanoparticle hydrogels in ionic solutions | Creates temporary conductive scaffold for patterning |

| Rose Bengal | Xanthene dye | Green light absorption (550 nm); 1-4% catalyst loading | Photocatalyst for oxidative polymerization |

| SIR-COOH | Silicon-rhodamine dye | Red light excitation (621 nm); Tissue penetration | Enables deep-tissue photopolymerization |

Quantitative Performance Characteristics

The performance of photopolymerized conductive structures depends critically on formulation parameters and processing conditions. Systematic characterization reveals key relationships between material composition and functional outcomes.

Table 2: Photopolymerization Parameters and Outcomes for 3E Monomers

| Monomer | Light Wavelength | Catalyst | Catalyst Loading | Time | Conversion | Conductivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3E-S (0.4 mg/mL) | 385 nm (UV) | None | 0% | 5 min | High | Comparable to enzymatic controls |

| 3E-S (0.4 mg/mL) | 550 nm (Green) | Rose Bengal | 4% | 5 min | >90% | Comparable to enzymatic controls |

| 3E-S (0.4 mg/mL) | 621 nm (Red) | SIR-COOH | 4% | 15 min | 70-80% | Slightly lower than green light |

| 3E-COONa (0.4 mg/mL) | 550 nm (Green) | Rose Bengal | 4% | 5 min | >90% | Comparable to enzymatic controls |

| 3E (4 mg/mL) | 550 nm (Green) | Rose Bengal | 4% | 5 min | Reduced (light absorption) | Requires increased surface area:volume |

The polymerization efficiency exhibits a strong dependence on catalyst concentration, with 4% Rose Bengal loading achieving near-complete monomer conversion within 5 minutes. Higher monomer concentrations (4 mg/mL versus 0.4 mg/mL) reduce reaction efficiency due to inner filter effects, necessitating optimized geometrical configurations to maintain performance [10].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Vivo Photopolymerization for Zebrafish Embryos

This protocol describes the formation of conductive patterns in zebrafish embryos, a established model for in vivo bioelectronic integration [10].

Materials and Reagents:

- 3E monomer solution (0.4 mg/mL in physiological buffer)

- Rose Bengal catalyst stock solution (2 mM in water)

- A5 nanoparticle dispersion (1 mg/mL in water)

- Custom light source with 550 nm filter (65 mW cm⁻² intensity)

- Glass capillaries for microinjection (1-2 μm tip diameter)

- Zebrafish embryos (24-48 hours post-fertilization)

Procedure:

Solution Preparation: Prepare working solution by mixing 3E monomer (0.4 mg/mL final concentration) with Rose Bengal (4% molar ratio relative to monomer) in physiological buffer.

Microinjection: Load working solution into glass capillary and inject approximately 10-50 nL into target region of zebrafish embryo using standard microinjection techniques.

Photomask Alignment: Position photolithography mask defining desired electrode pattern between light source and embryo. For simple geometries, direct illumination without masking may be employed.

Photopolymerization: Expose injected region to green light (550 nm, 65 mW cm⁻²) for 5 minutes. Monitor formation of dark blue-green coloration indicating polymer formation.

Validation: Confirm conductivity and pattern fidelity using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy or microscopic examination.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Incomplete polymerization may indicate insufficient catalyst concentration - increase Rose Bengal to 4% minimum.

- Tissue damage can result from excessive light intensity - maintain ≤65 mW cm⁻² for green light.

- Poor pattern resolution suggests light scattering - utilize red light (621 nm) with SIR-COOH for deeper penetration.

Protocol 2: Multi-Material Layering in Chicken Embryos

This advanced protocol enables creation of layered conductive structures through sequential photopolymerization, demonstrating the potential for complex 3D bioelectronic circuits [10].

Materials and Reagents:

- 3E-S monomer solution (0.4 mg/mL)

- A5 nanoparticle dispersion (1 mg/mL)

- SIR-COOH catalyst (2 mM in DMSO)

- Chicken embryos (embryonic day 3-5)

- Multiple photomasks with complementary patterns

- Dual-wavelength light source (550 nm and 621 nm)

Procedure:

A5 Hydrogel Formation: Inject A5 nanoparticle dispersion (50-100 nL) into target tissue region. Allow 10-15 minutes for natural hydrogel formation via ion absorption from tissue.

First Layer Patterning: Mix 3E-S monomer with SIR-COOH catalyst (4% molar ratio) and inject into A5 hydrogel matrix. Apply first photomask and expose to red light (621 nm) for 15 minutes to create initial conductive layer.

Second Layer Addition: Inject additional monomer-catalyst solution over first polymerized layer. Apply second photomask with complementary pattern and expose to red light for 15 minutes to create layered conductive architecture.

Integration Assessment: Examine layer interface via microscopy and characterize electrical connectivity between layers using custom microelectrodes.

Technical Notes:

- A5 hydrogel provides temporary conduction during patterning process

- Red light enables deeper tissue penetration for multi-layer structures

- Total procedure time: 45-60 minutes including hydrogel formation

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for in vivo photopolymerization of conductive patterns, illustrating key steps from solution preparation to functional interface validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for In Vivo Photopolymerization

| Reagent/Chemical | Function/Application | Working Concentration | Special Handling |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3E-S Monomer | Primary conductive polymer precursor | 0.4 mg/mL in physiological buffer | Light-sensitive; store protected from light |

| Rose Bengal | Green-light photocatalyst | 1-4% molar ratio relative to monomer | Prepare fresh solutions before use |

| SIR-COOH | Red-light photocatalyst | 4% molar ratio relative to monomer | DMSO stock solution; stable at 4°C |

| A5 Nanoparticles | Temporary conductive scaffold | 1 mg/mL in aqueous solution | Forms hydrogels in ionic environments |

| Physiological Buffer | Biocompatible solvent system | 1X concentration | Match osmolarity to target tissue |

| Photolithography Masks | Define electrode geometry | Custom patterns | Resolution down to 100 μm demonstrated |

Mechanism and Pathway Analysis

The photopolymerization process follows a single-electron transfer (SET) mechanism with oxygen consumption and hydrogen peroxide formation as key aspects of the reaction pathway [10]. Understanding this mechanism is essential for optimizing reaction conditions and troubleshooting failed polymerizations.

Figure 2: Photopolymerization mechanism pathway showing key steps from photon absorption to conductive network formation, highlighting the role of oxygen consumption and hydrogen peroxide formation.

Critical aspects of the mechanism include:

Photoinitiation: Photocatalyst excitation followed by single electron transfer from 3E monomer to excited catalyst, generating monomer radical cations.

Oxygen Dependency: Molecular oxygen serves as terminal electron acceptor, being consumed during the reaction and generating hydrogen peroxide as a byproduct.

Chain Propagation: Radical cations undergo coupling and deprotonation to form dimers, trimers, and eventually extended conjugated polymers.

Network Formation: In the presence of A5 nanoparticles, the growing polymer chains integrate with the existing conductive scaffold, enhancing mechanical stability and electrical continuity.

Evidence for this mechanism includes the observation that reaction cessation occurs when light is removed, with polymerization resuming only upon re-illumination. Furthermore, addition of catalase (which decomposes hydrogen peroxide) prevents further monomer conversion when added during the reaction, confirming the essential role of peroxide in the propagation cycle [10].

Applications and Integration Strategies

Photopolymerized PEDOT-S and 3E structures enable numerous advanced bioelectronic applications, particularly in neural interfaces and regenerative medicine. The technology demonstrates special promise for minimally invasive formation of conformal electrodes on soft, dynamic tissues like the brain [12] [4].

The resulting bioelectronics exhibit mechanical properties (elastic modulus ~0.1-10 MPa) much closer to neural tissue (1-4 kPa) than conventional metal electrodes (GPa range), significantly reducing inflammatory response and improving long-term signal stability [12]. The capability to create multi-layered, patterned circuits directly in living organisms enables sophisticated bioelectronic systems for precise neural stimulation and recording.

Integration with existing biomedical technologies includes:

- Neural Prosthetics: Forming conformal electrode arrays on peripheral nerves for advanced prosthetic control

- Deep Brain Stimulation: Creating soft electrode interfaces for treating Parkinson's disease and epilepsy

- Cardiac Pacemaking: Generating biocompatible conduction pathways for arrhythmia treatment

- Drug Delivery Systems: Combining conductive pathways with controlled release mechanisms

The photopolymerized structures naturally degrade after use without requiring surgical explanation, addressing a significant limitation of conventional bioelectronic implants [4].

Implementing In Vivo Photopolymerization: Techniques and Therapeutic Applications

The development of advanced bioelectronic devices for neural interfacing, targeted stimulation, and physiological monitoring relies on the ability to fabricate detailed, high-fidelity microelectrodes. Spatial patterning using photolithography masks is a foundational technique in this endeavor, enabling the precise definition of conductive traces and electrode sites at the micro-scale [13]. Within the broader context of a thesis on in vivo photopolymerization for bioelectronics, this methodology provides a critical bridge between design and realization. It allows for the creation of devices that are not only functionally complex but also mechanically compliant and biocompatible, which are essential characteristics for successful in vivo integration and long-term stability [14] [15]. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for utilizing photolithography masks to fabricate detailed electrodes, specifically framed for research in bioelectronics.

Underlying Principles and Key Comparisons

Photolithography is a process that uses light to transfer a geometric pattern from a photomask to a light-sensitive chemical photoresist on a substrate. In bioelectronics, this process defines the intricate patterns of metal (e.g., gold, platinum, copper) that form electrodes and interconnects on various substrates, including rigid silicon and flexible polymers.

A critical challenge in bioelectronic medicine is ensuring the long-term reliability and stability of implanted devices. The definitions of these key performance metrics are as follows [14]:

- Reliability: The probability that a device functions as intended without failure over a specified period under expected conditions.

- Stability: The ability of a device to maintain its functional and structural properties over time, resisting environmental and biological fluctuations.

- Durability: The physical resilience of a device to withstand external stresses like mechanical deformation and exposure to bodily fluids.

- Longevity: The total operational lifespan of a device before it becomes non-functional.

Different lithographic techniques offer varying balances of resolution, cost, and material compatibility. The table below summarizes key patterning technologies relevant to bioelectronics research.

Table 1: Comparison of Lithographic Techniques for Bioelectronic Fabrication

| Technique | Brief Summary | Resolution | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV Lithography [16] | Uses UV light and a mask to pattern a photoresist. | ≈1 µm | Simple, efficient, parallel processing allows mass production [16]. | Requires a cleanroom; resolution limited by diffraction; substrate must be flat [16]. |

| Two-Photon Lithography [16] | Uses UV light for patterning via two-photon polymerization. | ≈150 nm | Able to generate complex 3D structures [16]. | Time-expensive for large structures; large amount of data storage required [16]. |

| Electron Beam Lithography (EBL) [16] | Uses a focused electron beam to pattern a resist. | >10 nm | Precise control; can pattern complex geometries [16]. | Low throughput; complex and costly; proximity effect causes distortions [16]. |

| Cleanroom-Free Toolkit [15] | Integrates two-photon laser writing on a Parylene-C (PaC) mask and mask transfer. | Submicron | Cleanroom-free; compatible with solvent-sensitive biomaterials and flexible substrates like PDMS [15]. | Resolution limited by the mask material ablation process (not the laser itself) [15]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Photolithographic Fabrication of a Micro-electrode on a Carbon Steel Substrate

This protocol is adapted from a study demonstrating the fabrication of micro-electrodes for local hydrogen permeation measurements [13]. It highlights the use of an adhesion-promoting silica interlayer, a critical step for ensuring durability in electrochemical environments.

I. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Substrate | Base material for the electrode. | Carbon steel sheet, iron sheet (99.99% Fe) [13]. |

| Silica Precursors | Forms an adhesive and resistant inner layer. | Tetraethoxysilane (TEOS), Glycidyl 3-trimethoxysilylpropyl ether (GPTMS) [13]. |

| Positive Photoresist | Light-sensitive polymer for patterning. | OFPR-800 (Tokyo Ohka Kogyo) [13]. |

| Developer | Removes exposed regions of the photoresist. | NMD-3 (2.38% tetramethylammonium hydroxide) [13]. |

| Reactive Ion Etching (RIE) Gas | Removes the silica layer from exposed areas. | CHF3 gas [13]. |

II. Step-by-Step Methodology

- Substrate Preparation: Mechanically polish the steel or iron substrate to a fine finish (e.g., using #4000 SiC paper or 0.04 µm colloidal silica) [13].

- Silica Interlayer Deposition (Adhesion Promotion): a. Prepare a silica sol by mixing TEOS (or a mixture of TEOS and GPTMS) with ethanol in a 1:1 volumetric ratio. Add 1 mass% acetic acid or 0.004 M hydrochloric acid to catalyze the reaction and stir for at least 30 minutes [13]. b. Deposit the silica sol onto the substrate via spin-coating (e.g., 1500 rpm for 60 s, then 100 rpm for 60 s). c. Heat the coated specimen at 383 K (110 °C) for 15 minutes to 3 hours to form the silica layer [13].

- Photoresist Application: a. Spin-coat the positive photoresist (e.g., OFPR-800) onto the silica-coated surface at 2000 rpm for 60 s. b. Pre-bake the resist by heating at 368 K (95 °C) for 1.8 ks (30 minutes) to evaporate the solvent [13].

- Exposure and Development: a. Locally expose the photoresist to 405 nm wavelength light through a photomask defining the circle-shaped (or other) micro-electrode pattern. b. Immerse the specimen in the developer (NMD-3) to dissolve the exposed regions of the photoresist, revealing the underlying silica layer. c. Rinse with deionized water and perform a post-bake at 413 K (140 °C) for 30 minutes to harden the remaining resist [13].

- Silica Layer Etching: a. Use Reactive Ion Etching (RIE) with CHF3 gas (flow rate: 10 sccm, RF power: 100 W) to remove the silica layer from the exposed circular area, thereby unshrouding the underlying metal electrode surface [13].

- Final Processing: The device is now ready for electrochemical characterization (e.g., cathodic polarization) or integration into a larger bioelectronic system. The photoresist and silica layer together act as a robust insulating layer.

Protocol: Cleanroom-Free, Submicron Patterning on Flexible Substrates

This modern protocol outlines a simplified, cleanroom-free toolkit for patterning intricate bioelectronics on flexible substrates like PDMS, which is crucial for conformable in vivo devices [15].

Workflow Overview

Detailed Methodology

Step A: Direct Laser Writing Mask

- Begin by chemically vapor depositing (CVD) a 1-2 µm thick layer of Parylene-C (PaC) onto a pre-soaped glass substrate (soaping aids subsequent peel-off) [15].

- Use a two-photon laser to ablate and create the desired submicron electrode pattern directly into the PaC layer. This PaC layer serves as the physical etch mask.

Step B: Mask Transfer to Flexible Substrate Two primary strategies are employed:

- Strategy B1 (for optimal mask-substrate contact): Spin-coat uncured PDMS onto the PaC-on-glass substrate. Place the PaC mask face-down onto the PDMS. Use a vacuum to remove air gaps, then thermally cure the PDMS. Finally, peel off the glass substrate, leaving the PaC mask adhered to the PDMS [15].

- Strategy B2 (using Water-Soluble Adhesive - WSA): Use a layer of water-soluble adhesive (e.g., PVA-based 3M 5414) to peel the PaC mask from the glass and transfer it to the target flexible substrate. The WSA is later dissolved in water [15].

Step C: Material Deposition and Patterning

- With the PaC mask securely on the substrate, deposit the functional material (e.g., metal for electrodes) using a dry process like Physical Vapor Deposition (PVD) or a wet process like spin-coating [15].

- The pattern is achieved by peeling off the PaC mask (a "lift-off" process), leaving behind the material deposited only in the patterned areas [15].

Step D: Multi-layer/Material Assembly

- For complex devices with multiple layers, use the PaC mask in conjunction with WSA and a micron-precision aligner (e.g., Finetech aligner) for additive materials processing [15].

- This allows for precise alignment of subsequent layers of electrodes, insulators, and encapsulation, enabling the fabrication of intricate bioelectronic devices like transistor arrays and multi-electrode probes entirely without a cleanroom [15].

Application Notes & Troubleshooting

- Adhesion Failure: Poor adhesion of the photoresist to metal substrates is a common issue, leading to peeling during development or electrochemical testing [13]. The protocol in Section 3.1 directly addresses this by implementing a silica interlayer derived from TEOS or a TEOS/GPTMS mixture, which significantly improves durability and impedance in acidic environments [13].

- Material Compatibility for In Vivo Use: Traditional lithography uses solvents and resists that can degrade sensitive biomaterials. The cleanroom-free toolkit in Section 3.2 is specifically designed to be compatible with a wider range of functional and encapsulation biomaterials, as it avoids aggressive solvents and uses a physical PaC mask [15].

- Substrate Flexibility: Standard photolithography requires exceptionally flat, rigid substrates. The phase mismatch between a stiff photoresist and a soft elastomer like PDMS can lead to cracking [15]. The cleanroom-free method, which transfers a flexible PaC mask directly onto PDMS or other conformable surfaces, overcomes this limitation and is ideal for flexible and implantable bioelectronics [15].

- Resolution vs. Practicality: While EBL and two-photon lithography offer nanometer resolution, many bioelectronic applications (e.g., neural electrodes) require only submicron resolution. The cleanroom-free toolkit achieves this submicron resolution at a lower cost and complexity, making it highly practical for research labs [15].

The integration of bioelectronics within living organisms presents a unique challenge: creating conductive structures that are both biocompatible and geometrically precise. Traditional implanted electrodes often cause inflammation and scarring due to their rigidity and mechanical mismatch with soft biological tissues [10] [4]. While in situ-formed conductive polymers offer improved biocompatibility, they typically lack spatial control, with curing times spanning several hours to days [10] [1].

Photopolymerization using green and red light has emerged as a transformative strategy to overcome these limitations. This approach enables the direct formation of soft, conductive materials within the body using wavelengths that penetrate tissue effectively and minimize photodamage [10] [4]. The following application notes detail the specific parameters, protocols, and material considerations for implementing these light source strategies in deep-tissue curing for advanced bioelectronics.

Light Parameter Comparison and Selection

Selecting the appropriate wavelength is critical for balancing tissue penetration, curing efficiency, and biocompatibility. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of green and red light for photopolymerization in vivo.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Green and Red Light for In Vivo Photopolymerization

| Parameter | Green Light Strategy | Red Light Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Wavelength | 550 nm [10] | 621 nm [10] |

| Photocatalyst | Rose Bengal [10] | SIR-COOH [10] |

| Typical Curing Time | 5 minutes [10] | 15 minutes [10] |

| Light Intensity | 65 mW cm⁻² [10] | Information not specified in search results |

| Tissue Penetration | Moderate | Superior (Within the near-infrared window of 600-1300 nm) [10] |

| Polymerization Outcome | Standard polymer formation | Enhanced higher-order structure formation (e.g., trimers) [10] |

| Key Advantage | Rapid curing | Deeper tissue penetration and complex polymer structures |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Photopolymerization with Green Light

This protocol describes the formation of conductive polymers within a tissue environment using green light activation, ideal for applications requiring rapid curing [10].

Materials Required:

- Monomer solution: 3E-S derivative (0.4 - 4 mg mL⁻¹ in aqueous solution) [10].

- Photocatalyst: Rose Bengal (4% catalyst loading relative to monomer) [10].

- Light Source: LED lamp emitting at 550 nm, capable of delivering 65 mW cm⁻² at the target site [10].

- Photomask (optional): For defining precise conductive patterns [10] [1].

- Animal model (e.g., zebrafish or chicken embryo) [10].

Procedure:

- Monomer-Catalyst Preparation: Mix the 3E-S monomer solution with Rose Bengal photocatalyst to achieve a final catalyst loading of 4% (w/w). Protect the solution from ambient light until irradiation [10].

- In Vivo Administration: Introduce the prepared monomer-catalyst solution into the target tissue of the animal model via injection or other suitable delivery methods [10].

- Light Exposure:

- Curing Validation: A successful reaction is indicated by a visible color change to a dark blue-green hue at the polymerization site. The resulting material is a soft, conductive hydrogel integrated with the surrounding tissue [10] [4].

Protocol B: Photopolymerization with Red Light

This protocol utilizes red light for deeper tissue penetration and the formation of more complex conductive polymer structures, suitable for targets beneath more substantial tissue layers [10].

Materials Required:

- Monomer solution: 3E-S or 3E-COONa derivative (0.4 mg mL⁻¹ in aqueous solution) [10].

- Photocatalyst: SIR-COOH [10].

- Light Source: LED lamp emitting at 621 nm [10].

- Photomask (optional) [10] [1].

- Animal model [10].

Procedure:

- Monomer-Catalyst Preparation: Combine the 3E monomer with the SIR-COOH photocatalyst. The exact optimal catalyst loading should be determined empirically, following the principle of increasing conversion with higher catalyst load [10].

- In Vivo Administration: Administer the solution to the target tissue in vivo [10].

- Light Exposure: Irradiate the target area with 621 nm red light for approximately 15 minutes. Use a photomask for spatial control if needed [10] [1].

- Curing Validation: Confirm polymerization via the characteristic dark blue-green color and an additional absorption band at 800 nm, which indicates an oxidized polymer and the potential formation of higher-order oligomers like trimers [10].

Workflow and Signaling Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and the underlying Single Electron Transfer (SET) mechanism for the photopolymerization process in vivo.

Diagram 1: In Vivo Photopolymerization Workflow and Mechanism. This diagram outlines the experimental sequence from monomer administration to the formation of a conductive hydrogel within tissue, including the key Single Electron Transfer (SET) chemical mechanism driven by light.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of these light strategies requires specific materials. The table below lists essential reagents and their functions.

Table 2: Key Reagents for In Vivo Photopolymerization

| Reagent | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| 3E Monomers (3E-S, 3E-COONa) | Novel EDOT-trimer monomers with low oxidation potential, enabling polymerization under mild, biocompatible conditions with visible light [10]. |

| Rose Bengal | A photocatalyst activated by green light (550 nm) to initiate the oxidative polymerization reaction via a SET mechanism [10]. |

| SIR-COOH | A far-red-shifted rhodamine analog photocatalyst that allows activation with deeper-penetrating red light (621 nm) [10]. |

| A5 (PEDOT-S derivative) | A conductive polymer nanoparticle that forms a temporary ion-linked hydrogel in vivo, providing a scaffold for the photopolymerized structure [10]. |

| Photolithography Masks | Physical masks used to block light in specific patterns, enabling the creation of detailed and layered 2D and 3D conductive circuits directly in tissue [10] [1]. |

The development of layered and 3D circuitry within the body represents a frontier in bioelectronic medicine, enabling advanced therapeutic and diagnostic capabilities. In vivo photopolymerization has emerged as a transformative approach for creating conformal, biocompatible electronic interfaces directly on or within biological tissues. This paradigm shift moves beyond traditional rigid implants toward soft, seamless biointegrated devices that can monitor and modulate physiological processes with high precision. The convergence of vat photopolymerization (VP) techniques from additive manufacturing with bioelectronic materials creates unprecedented opportunities for forming complex conductive structures in situ.

Recent advances in visible-light-induced polymerization of water-soluble conducting polymer precursors now enable direct formation of high-performance organic mixed ion-electron conductors (OMIECs) on biological surfaces [17]. This initiator-free photochemical process allows seamless film deposition and manufacturing of organic electrochemical transistors (OECTs) across rigid, flexible, and biological substrates, including direct application to mouse skin in vivo. These OMIECs provide unique coupled dual charge transport characteristics alongside mechanical softness, biocompatibility, and stability—essential properties for functional bioelectronic interfaces [17].

Current Technical Approaches and Quantitative Performance

Photopolymerization Techniques for Bioelectronics

Vat photopolymerization (VP) technologies encompass several light-based additive manufacturing techniques capable of creating high-resolution 3D structures from liquid resins. For bioelectronic applications, the most relevant VP modalities include:

- Digital Light Processing (DLP): Projects planar 2D images for layer-by-layer fabrication, enabling rapid production of complex structures with feature sizes determined by pixel resolution (∼1-100 μm) [18].

- Stereolithography (SLA): Utilizes a laser raster-scanned along the vat volume to crosslink resin in a point-by-point manner, achieving high precision for biomedical constructs [19].

- Multi-photon Lithography (MPL): Enables sub-100 nm resolution through two-photon absorption processes, overcoming optical diffraction barriers for ultra-high feature definition [18].

- Volumetric Additive Manufacturing (VAM): Projects sliced images into a synchronized rotating vat from multiple angles, allowing rapid (>50 cm/h) layerless fabrication and unique capability for overprinting around existing 3D structures [18].

The recent introduction of visible-light-driven aqueous polymerization represents a significant advancement for in vivo applications, as it eliminates the need for oxidants, metal catalysts, or organic solvents that limit biocompatibility and scalability [17]. This approach enables direct photopatterning of OMIECs on biological substrates, forming conformal interfaces for neural recording and other bioelectronic functions.

Performance Metrics of Photopolymerized Bioelectronic Devices

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of Photopolymerized Organic Mixed Ion-Electron Conductors

| Performance Parameter | Reported Value | Significance for Bioelectronics |

|---|---|---|

| Electrical Conductivity | State-of-the-art performance [17] | Ensures efficient signal transduction for recording and stimulation |

| Electrochemical Properties | Optimized for device function [17] | Enables stable operation in biological environments |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Significantly enhanced in vivo [17] | Improves fidelity of neural and physiological recordings |

| Thickness Range | Ultra-thin, conformal films [17] | Promotes seamless biointegration and minimal tissue response |

| Fabrication Compatibility | Direct patterning on biological substrates [17] | Enables in situ formation of complex circuitry |

Table 2: Comparison of Photopolymerization Techniques for Bioelectronic Fabrication

| Technique | Resolution | Fabrication Speed | Key Advantages | Biological Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Light Processing (DLP) | ∼1-100 μm [18] | Fast (layer-based) | High precision for architectural gradients [19] | Moderate (depends on resin) |

| Stereolithography (SLA) | <100 μm [19] | Moderate | Precise control over mechanical properties [19] | Moderate (depends on resin) |

| Multi-photon Lithography (MPL) | Sub-100 nm [18] | Slow | Unparalleled feature resolution [18] | Moderate (depends on resin) |

| Visible-Light Aqueous Polymerization | Micrometer scale [17] | Rapid | Excellent biocompatibility, in situ application [17] | High (water-based, initiator-free) |

| Volumetric Additive Manufacturing (VAM) | ∼100 μm [18] | Very fast (>50 cm/h) | Layerless fabrication, overprinting capability [18] | Moderate (depends on resin) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: In Vivo Photopolymerization of OMIECs on Biological Surfaces

Principle: This protocol describes the initiator-free, visible-light-induced polymerization of water-soluble conducting polymer precursors directly on biological substrates for forming biocompatible, high-performance OMIECs [17].

Materials:

- Water-soluble conducting polymer precursors (specific chemical identities not disclosed in source)

- Visible light source (wavelength optimized for polymerization)

- Biological substrate (e.g., mouse skin, neural tissue)

- Application apparatus for precursor solution

- Protective atmosphere (if required)

- Characterization equipment (electrical, electrochemical)

Procedure:

- Precursor Solution Preparation: Prepare aqueous solution of conducting polymer precursors at optimal concentration for film formation and electrical performance.

- Substrate Preparation: Gently clean biological substrate surface while maintaining tissue viability. Ensure surface is accessible for application and polymerization.

- Solution Application: Apply precursor solution uniformly to target area of biological substrate using controlled deposition technique.

- Photopolymerization: Expose coated substrate to visible light at specified intensity and duration to initiate polymerization. Optimize parameters to achieve complete conversion while preserving tissue integrity.

- Pattern Definition: Utilize photomasks or focused light for spatial control over conductor formation, creating defined circuit patterns.

- Post-Processing: Rinse gently with physiological buffer to remove unreacted precursors if necessary.

- Characterization: Validate electrical properties, adhesion, and biocompatibility through appropriate in vivo measurements.

Technical Notes:

- Light intensity and exposure time must be carefully balanced to achieve complete polymerization without tissue damage.

- Precursor concentration and solution viscosity affect final film thickness and conformality.

- The process enables manufacturing of OECTs directly on biological surfaces for neural recording and other bioelectronic applications [17].

Protocol: Fabrication of Gradient Scaffolds with Embedded Circuitry via Vat Photopolymerization

Principle: This protocol leverages vat photopolymerization to create continuous gradient scaffolds with compositional, architectural, and mechanical gradients that mimic native tissue organization while incorporating conductive elements [19].

Materials: