Bioelectronic Medicine vs. Pharmaceutical Outcomes: A Comparative Analysis for the Future of Therapeutics

This article provides a comprehensive comparison for researchers and drug development professionals on the evolving paradigms of bioelectronic medicine and traditional pharmaceuticals.

Bioelectronic Medicine vs. Pharmaceutical Outcomes: A Comparative Analysis for the Future of Therapeutics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison for researchers and drug development professionals on the evolving paradigms of bioelectronic medicine and traditional pharmaceuticals. It explores the foundational principles of bioelectronic devices, which use electrical signals to modulate neural circuits, contrasting them with systemic drug actions. The analysis covers current methodologies, key applications in neurology and cardiology, and addresses critical challenges including device reliability, cost, and regulatory hurdles. By evaluating clinical and economic outcomes, this review synthesizes evidence on where bioelectronic therapies offer superior precision, reduced side effects, and long-term value, outlining a future where integrated approaches could redefine disease management.

Principles and Paradigms: Understanding the Core Mechanisms of Bioelectronic and Pharmaceutical Therapies

The pursuit of effective therapies has historically been dominated by pharmaceuticals, which rely on systemic chemical interactions. In contrast, bioelectronic medicine represents a paradigm shift, using targeted energy to modulate neural circuits. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two approaches, focusing on their mechanisms, applications, and experimental validation for researchers and drug development professionals.

Systemic drug action involves the administration of chemical compounds that distribute throughout the body via the bloodstream to interact with biological targets, while targeted neuromodulation uses electrical, magnetic, or other forms of energy to precisely modulate the activity of specific neural circuits or nerves [1]. The fundamental distinction lies in their therapeutic delivery: drugs act chemically and systemically, whereas neuromodulation acts physically and locally. Understanding their comparative profiles is crucial for selecting appropriate therapeutic strategies for specific conditions and advancing biomedical research.

Mechanisms of Action: From Molecular Diffusion to Circuit Precision

Systemic Drug Pharmacology

Systemic drugs produce their effects through pharmacokinetic (what the body does to the drug) and pharmacodynamic (what the drug does to the body) processes. After administration, drugs undergo absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion, leading to widespread circulation. Their therapeutic effects emerge from interactions with molecular targets such as receptors, enzymes, and ion channels [2].

For example, the newly approved drug suzetrigine, a non-opioid analgesic, exerts its effect by selectively blocking the NaV1.8 voltage-gated sodium channel in peripheral sensory neurons, inhibiting pain signal generation [3]. Similarly, acoltremon, a treatment for dry eye disease, acts as an agonist of transient receptor potential melastatin 8 (TRPM8) thermoreceptors on corneal sensory nerves, triggering increased basal tear production [3]. These molecular interactions, while specific, occur wherever the drug distributes, potentially leading to off-target effects.

Neuromodulation Mechanisms

Neuromodulation techniques interface with electrically active tissues to restore dysfunctional neural circuitry. These approaches can be broadly categorized into invasive and non-invasive modalities:

- Non-invasive techniques include repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). rTMS uses alternating magnetic fields to induce electric currents in superficial cortical neurons according to Faraday's law of electromagnetic induction, with stimulation frequency determining the direction of neuroplastic changes [4].

- Invasive techniques such as deep brain stimulation (DBS) involve surgical implantation of electrodes to deliver electrical pulses to deep brain structures [5].

The therapeutic effect arises from modulating neural pathway activity rather than chemical receptor binding. For substance use disorders, both invasive and non-invasive neuromodulation target components of the mesocorticolimbic pathways, including the ventral striatum, nucleus accumbens, and prefrontal cortex [4]. Advanced approaches are evolving toward "closed-loop" systems that monitor physiological signals and adjust stimulation parameters in real-time for personalized therapy [6].

Table 1: Fundamental Mechanisms of Action

| Feature | Systemic Drug Action | Targeted Neuromodulation |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Chemical interaction with molecular targets | Physical energy modulation of neural activity |

| Therapeutic Specificity | Molecular target specificity | Anatomical and circuit specificity |

| Distribution | Systemic via bloodstream | Focal or targeted delivery |

| Reversibility | Dependent on drug half-life | Instantaneously adjustable |

| Metabolism | Hepatic metabolism and renal excretion | No metabolic processing required |

Comparative Performance Data: Quantitative Outcomes Analysis

Efficacy Metrics Across Indications

Substance Use Disorders (SUDs): Neuromodulation shows promising efficacy for challenging conditions like opioid and stimulant use disorders. For methamphetamine use disorder, a large randomized controlled trial of 126 participants found that intermittent theta burst stimulation to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) significantly reduced cue-induced craving compared to sham treatment [5]. For cocaine use disorder, systematic reviews indicate that high-frequency (≥5 Hz) rTMS protocols targeting the left DLPFC significantly reduced self-reported cue-induced craving, impulsivity, and, in some cases, cocaine use compared to controls [4].

Pain Management: The newly approved non-opioid analgesic suzetrigine demonstrated significant pain reduction in surgical pain trials. In abdominoplasty and bunionectomy patients, suzetrigine (100 mg initially, then 50 mg every 12 hours) showed significantly greater pain reduction (SPID48 values of 118.4 and 99.9, respectively) compared to placebo (70.1 and 70.6) [3]. This performance was similar to hydrocodone/acetaminophen in one trial but slightly lower in another, offering a non-addictive alternative with a different safety profile.

Neurological Disorders: Deep brain stimulation has established efficacy for movement disorders, with long-term outcomes (15 years) showing sustained benefits for Parkinson's disease patients [7]. Spinal cord stimulation, representing a market value of $2.92 billion in 2023, demonstrates the economic and therapeutic significance of neuromodulation for chronic pain [1].

Table 2: Quantitative Efficacy Comparison Across Therapeutic Areas

| Condition | Therapeutic Approach | Efficacy Outcomes | Evidence Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cocaine Use Disorder | High-frequency rTMS to left DLPFC | Significant reduction in craving and impulsivity | Systematic review of 8 RCTs [4] |

| Methamphetamine Use Disorder | Theta burst stimulation to DLPFC | Significant decline in cue-induced craving | RCT of 126 participants [5] |

| Moderate-to-Severe Acute Pain | Suzetrigine (50-100 mg) | SPID48: 118.4 (abdominoplasty), 99.9 (bunionectomy) | Two controlled trials (N=2,191) [3] |

| Dry Eye Disease | Acoltremon 0.003% solution | >40% patients with >10-mm increase in Schirmer score | Two Phase III trials (N=930) [3] |

| Parkinson's Disease | Deep Brain Stimulation | Significant improvement in tremors, bradykinesia, rigidity | Long-term 15-year outcomes [7] |

Safety and Tolerability Profiles

Systemic drugs frequently exhibit class-specific adverse effects. Suzetrigine demonstrates side effects including itching, rash, muscle spasms, increased creatine phosphokinase, and decreased estimated glomerular filtration rate [3]. Acoltremon primarily causes instillation-site pain (50% of patients), though less than 1% discontinue due to these sensations [3].

Neuromodulation safety profiles differ substantially. Non-invasive approaches like rTMS and tDCS are generally well-tolerated, with no serious adverse events reported in systematic reviews of SUD applications [4]. Invasive DBS carries risks associated with surgical implantation, including infection and hardware complications, but avoids systemic pharmacological side effects [5]. The bioelectronic medicine field is addressing safety through technological advances in soft, flexible bioelectronic devices that minimize mechanical mismatch with biological tissues, reducing inflammation and improving long-term biocompatibility [6].

Experimental Methodologies: Protocols for Validation

Clinical Trial Designs for Neuromodulation

Randomized, sham-controlled, double-blind trials represent the gold standard for evaluating neuromodulation therapies. In rTMS trials for substance use disorders, common methodologies include:

- Stimulation Parameters: High-frequency (≥5 Hz) protocols for increasing cortical excitability versus low-frequency (≤1 Hz) for decreasing excitability [4]

- Target Localization: Neuronavigation systems using individual MRI scans for precise targeting of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex or other regions [5]

- Sham Conditions: Placebo coils that replicate the sound and superficial sensation without delivering active neural stimulation [4]

- Outcome Measures: Primary endpoints including self-reported craving scales, cognitive function assessments, and biological measures of substance use [4]

For example, recent rTMS studies employ accelerated paradigms compressing full treatment courses into 5 days rather than traditional 4-6 week regimens, improving retention and feasibility [5]. Theta burst stimulation protocols deliver patterned high-frequency stimulation in shorter sessions while maintaining efficacy comparable to conventional rTMS [5].

Drug Development and Validation Protocols

Pharmaceutical validation follows established regulatory pathways with specific adaptations for novel mechanisms:

- Phase III Trial Designs: For suzetrigine, two controlled trials in acute surgical pain models (abdominoplasty and bunionectomy) using the SPID48 (sum of pain intensity differences over 48 hours) primary endpoint with active (hydrocodone/acetaminophen) and placebo comparators [3]

- Biomarker Validation: For targeted therapies, demonstration of target engagement through functional imaging or electrophysiological measures

- Dosing Optimization: Identification of minimal effective doses and maximum tolerated doses through phase II dose-ranging studies

Novel drug classes require specialized validation approaches. For instance, drugs like acoltremon first require establishing proof of concept for novel targets (TRPM8 receptors) before progressing to large efficacy trials [3].

Signaling Pathways and Neural Circuits: Visualization Frameworks

Systemic Drug Signaling Pathways

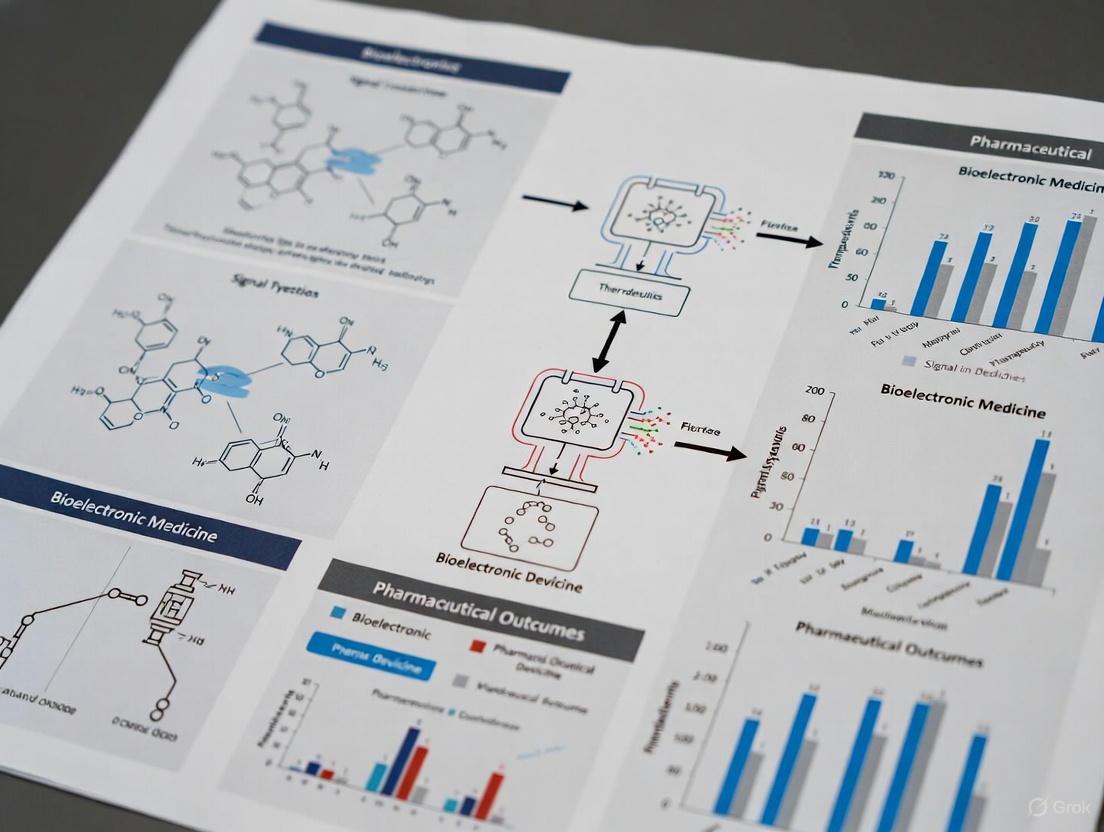

Diagram 1: Systemic Drug Action Pathway

Neuromodulation Neural Circuitry

Diagram 2: Targeted Neuromodulation Circuit

Experimental Platforms and Reagents

Table 3: Research Toolkit for Therapeutic Development

| Tool Category | Specific Technologies | Research Applications | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug-Target Databases | HCDT 2.0, BindingDB, PharmGKB [8] | Drug discovery, target identification | Curated drug-gene, drug-RNA, drug-pathway interactions |

| Neuromodulation Devices | Deep TMS systems, tDCS devices, DBS implants [4] [5] | Circuit mapping, therapeutic testing | Precise neural stimulation with varying penetration depths |

| Genetic Targeting Tools | Optogenetics, Chemogenetics, Magnetogenetics [9] [7] | Cell-type specific modulation | Selective manipulation of defined neuronal populations |

| Bioelectronic Materials | Conducting polymers, Graphene, Carbon nanotubes [1] | Device development, tissue interface | Improved biocompatibility and signal transduction |

| Computational Modeling | QSP models, Machine learning, PBPK modeling [2] | Predictive therapeutic optimization | Simulation of drug effects and neuromodulation parameters |

The comparison between systemic drug action and targeted neuromodulation reveals complementary rather than competing therapeutic profiles. Pharmaceuticals offer molecular precision with systemic distribution, while neuromodulation provides anatomical precision with localized effects. The emerging field of bioelectronic medicine represents a convergence of these approaches, leveraging advances in materials science, microelectronics, and neural circuit understanding to develop increasingly sophisticated therapeutic platforms [6] [1].

Future therapeutic development will likely integrate both modalities, with pharmaceuticals potentially enhancing or being enhanced by targeted neuromodulation approaches. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the comparative strengths, limitations, and methodological requirements of each approach is essential for designing optimal treatment strategies for specific conditions and patient populations. The growing market for bioelectronic medicine, projected to reach $33.59 billion by 2030, reflects the increasing importance of these technologies in the therapeutic landscape [10].

Electroceuticals, or bioelectronic medicine, represent a transformative class of therapies that use electrical signals to modulate the body's electrically active tissues—such as nerves, the heart, and the brain—to treat disease [11] [1]. This approach stands in contrast to traditional pharmaceuticals, which rely on systemic chemical interactions. The core premise is that by precisely interfacing with the nervous system, which innervates every organ in the human body, bioelectronic devices can selectively modulate organ function, offering targeted treatment with the potential for reduced side effects compared to drug administration [1]. The global market for these therapies is expanding rapidly, valued at USD 23.54 billion in 2024 and projected to reach USD 33.59 billion by 2030, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6.10% [10]. This growth is driven by the rising prevalence of chronic diseases, an aging population, and continuous technological innovations [10] [12].

This guide objectively traces the evolution of electroceuticals from ancient anecdotes to modern implantable devices, framing this progression within the broader research context comparing bioelectronic and pharmaceutical outcomes. It is structured to provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a clear comparison of device performance across historical periods, detailed experimental methodologies, and essential research tools.

Historical Timeline and Technological Progression

The development of electroceuticals has progressed from foundational discoveries of bioelectricity to sophisticated, intelligent implants. The timeline below visualizes this journey through key milestones.

Figure 1: Evolution of electroceuticals from ancient times to the modern era, highlighting key technological transitions.

Ancient Origins and Foundational Discoveries

The earliest records of bioelectronic medicine date back to ancient civilizations, including Egypt and Greece, where electric fish were used to deliver therapeutic shocks for ailments like headaches, migraines, and gout [1] [13]. This constituted the first documented instance of non-invasive neuromodulation. The field's scientific foundation was laid in the late 18th century by Luigi Galvani, whose experiments demonstrated that electrical stimulation could cause muscle contraction in frog legs, introducing the concept of "bioelectricity" [6] [1] [13]. Alessandro Volta's subsequent development of the battery further enabled the therapeutic application of electricity for conditions such as paralysis and pain relief [13].

The Dawn of Modern Implants

The mid-20th century marked the transition from concept to clinical device. The first fully implantable pacemaker was developed in 1958 by Åke Senning and Rune Elmqvist, providing a reliable, long-term solution for cardiac arrhythmias and representing a pivotal moment for fully implantable bioelectronic systems [1] [13]. This was followed by the first cochlear implant for profound deafness in 1961 [1]. These early devices were open-loop systems, meaning they delivered fixed stimulation patterns without responding to the body's changing physiological needs [13].

The Rise of Neuromodulation

From the 1980s to the 2000s, the scope of bioelectronic medicine expanded beyond the heart and ears to the central and peripheral nervous systems. Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) emerged as a reversible and adjustable therapy for movement disorders like Parkinson's disease, receiving FDA approval for essential tremor in 1997 [1] [13]. Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) was developed for treatment-resistant epilepsy and depression, later showing promise for modulating immune responses and inflammation in conditions like rheumatoid arthritis [11] [13]. This period also saw the advent of rate-responsive pacemakers, which could adapt to a patient's activity level, representing an early step toward closed-loop systems [13].

The Modern Era of Intelligent Bioelectronics

The 21st century has ushered in the current generation of "intelligent" electroceuticals, characterized by four key trends:

- Closed-Loop Systems: Devices like the Medtronic Percept DBS system and closed-loop spinal cord stimulators can sense physiological signals and adjust stimulation parameters in real time, moving from continuous to on-demand, responsive therapy [12] [13].

- Miniaturization and Wireless Power: Devices are becoming smaller, with some pacemakers now smaller than a grain of rice. The shift toward battery-free implants, powered by wireless energy transfer methods like inductive coupling and ultrasound, eliminates the need for replacement surgery and improves device longevity [14] [1].

- Soft and Flexible Bioelectronics: Researchers are shifting from rigid materials to soft, conformable devices using stretchable electronics and hydrogels. This reduces the mechanical mismatch with biological tissues, minimizing inflammation and improving long-term signal stability [6].

- Integration with AI and Digital Health: Artificial intelligence is being leveraged to analyze patient data for personalized treatment protocols, while wearable companions and cloud connectivity enable remote monitoring and therapy adjustment [15] [10].

Comparative Performance Analysis of Electroceuticals

The evolution of device technology has directly translated into improved clinical performance and patient outcomes. The table below provides a structured comparison of key electroceutical devices across different stages of development.

Table 1: Performance and Outcome Comparison of Representative Electroceutical Devices

| Device / Therapy | Era of Adoption | Key Technological Parameters | Reported Efficacy Outcomes | Advantages over Pharmacological Counterparts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac Pacemaker [11] [13] | 1958 (First Implant) | Fixed-rate pacing; Early devices were open-loop. | Restored heart rhythm in patients with complete heart block. | Provided a life-saving intervention where drugs were often ineffective for complete heart block. |

| Rate-Responsive Pacemaker [13] | 1980s | Integrated sensors for activity; Early closed-loop feedback. | Improved quality of life and survival by adapting to patient activity. | More physiological response compared to fixed-rate pacing; superior to chronotropic drugs. |

| Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) for Parkinson's [1] [12] [13] | 1990s-2000s (Clinical Adoption) | Adjustable frequency, amplitude, pulse width; Initially open-loop. | Significant reduction in tremor and rigidity in majority of patients. | Reversible and adjustable alternative to ablative surgery; reduced motor symptoms where drugs lost efficacy. |

| Closed-Loop DBS (Medtronic Percept) [12] [13] | 2020 (FDA Approval) | Sensing and stimulation with BrainSense technology; adaptive stimulation. | Real-time adjustment based on neural signals for improved symptom control. | Personalized therapy; potential for managing non-motor symptoms; more efficient energy use. |

| Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) for Epilepsy [11] [12] | 1990s-2000s | Implantable pulse generator with programmable output. | Meaningful seizure reduction in a significant portion of drug-resistant patients. | Effective for drug-resistant epilepsy; non-pharmacological mechanism of action. |

| VNS for Depression [12] | 2000s | Similar to epilepsy devices, with different stimulation parameters. | 71% of treatment-resistant patients achieved meaningful symptom relief. | Durable option for treatment-resistant depression (TRD), where multiple drug classes fail. |

| Closed-Loop Spinal Cord Stimulation (SCS) for Pain [12] | 2022-2024 (FDA Approvals) | Real-time adjustment based on physiological feedback. | 93% pain-reduction success in chronic pain cases. | Superior pain control and reduced opioid reliance compared to conventional SCS and systemic opioids. |

Experimental Protocols in Modern Electroceutical Development

The advancement of modern electroceuticals relies on rigorous experimental methodologies. Below are detailed protocols for two key areas: evaluating wireless power transfer and assessing efficacy in chronic wound healing.

Protocol: Evaluating Wireless Power Transfer for Implantable Devices

Objective: To systematically investigate and optimize radiation efficiency and in-body path loss for robust wireless links in implantable systems [16].

Materials:

- Transmitting Coil/System: External power transmitter (e.g., RF signal generator, ultrasonic transducer).

- Implantable Receiver: Miniaturized receiving coil or antenna integrated into the device.

- Tissue Simulant: A medium that mimics the dielectric properties of human tissue (e.g., saline solution, specialized phantom gel).

- Network Analyzer: To measure S-parameters and calculate power transfer efficiency.

- Thermocouples: To monitor localized temperature changes and ensure safety limits are not exceeded.

Methodology:

- System Setup: The implantable receiver is embedded within the tissue simulant at a predetermined depth and orientation. The external transmitter is positioned at a specified distance from the simulant surface.

- Frequency Sweep: The operating frequency of the external transmitter is swept across a defined range (e.g., kHz to GHz for RF, MHz for ultrasound) while the network analyzer records the power received by the implant.

- Efficiency Calculation: The radiation efficiency is calculated as the ratio of the power received by the implant to the power input to the transmitter, accounting for losses in the intervening medium [16].

- Parameter Optimization: The process is repeated while varying key parameters, including:

- Source Type: Comparing inductive coupling, ultrasonic, and magneto-electric transfer [14] [1].

- Encapsulation Size and Material: Evaluating the impact of the device's hermetic package on efficiency [16].

- Alignment: Assessing the effect of angular and lateral misalignment between transmitter and receiver [14].

- Validation: The optimized configuration is validated in ex vivo or in vivo models to confirm performance in a biological environment. The goal is to achieve a 5- to 10-fold improvement in radiation efficiency or gain [16].

Protocol: Assessing Electrostimulation Efficacy in Chronic Wound Healing

Objective: To determine the effect of controlled micro-electrostimulation on reactivating endogenous bioelectric activities and cellular processes critical for healing chronic wounds [17].

Materials:

- Electroceutical Device: A wearable, wireless stimulator (e.g., a triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG) or an inductively powered patch) [14] [17].

- Animal Model: Diabetic (e.g., db/db) mice or other validated models of impaired wound healing.

- Electrodes: Biocompatible, flexible electrodes placed in the wound periphery.

- Histology Equipment: For tissue fixation, sectioning, and staining (H&E, Masson's Trichrome).

- Immunofluorescence Microscopy: For visualizing specific cell types and proteins.

Methodology:

- Wound Creation: A full-thickness cutaneous wound is created on the dorsum of anesthetized animals.

- Group Allocation: Animals are randomly assigned to:

- Treatment Group: Receives active electrical stimulation via the implanted device.

- Control Group: Wears an identical but inactive device (sham stimulation).

- Stimulation Parameters: The treatment group receives stimulation using predefined parameters, typically Pulsed Current (e.g., 1.2–1.5 mA), which is better suited for wound healing due to lower side effects compared to direct current [17]. Common settings include low-frequency pulses (e.g., 50-100 Hz) for a set duration daily.

- Outcome Measures:

- Primary: Wound closure rate, measured by tracing the wound area daily until complete healing.

- Secondary: Histological analysis of granulation tissue thickness, collagen deposition, and re-epithelialization. Immunofluorescence is used to quantify key cells (e.g., macrophage transition from M1 to M2 phenotype) and markers of angiogenesis (e.g., CD31) [17].

- Data Analysis: Wound healing times and histological scores are compared between groups using statistical tests (e.g., t-test, ANOVA). A successful outcome is a statistically significant acceleration of wound healing in the treatment group, coupled with evidence of enhanced cellular proliferation and migration.

Research Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

The following table details key materials and technologies that are foundational to current research and development in the field of bioelectronic medicine.

Table 2: Essential Research Toolkit for Advanced Bioelectronic Device Development

| Item / Technology | Category | Primary Function in R&D |

|---|---|---|

| Conducting Polymers (e.g., PEDOT:PSS) [1] | Electrode Material | Seamlessly bridge biotic/abiotic interface; reduce impedance for safer device miniaturization; mixed ionic/electronic conductivity improves signal fidelity. |

| Soft & Stretchable Materials (e.g., Hydrogels, Elastomers) [6] [14] | Substrate/Encapsulation | Minimize mechanical mismatch with tissue; reduce foreign body reaction (FBR) and fibrosis; enable conformable, long-lasting implants. |

| Triboelectric Nanogenerators (TENGs) [14] [17] | Power Supply | Harvest mechanical energy (e.g., body movement, ultrasound) to generate electrical stimulation; enable self-powered, battery-free devices. |

| Inductive Coupling Systems [11] [14] | Power Transfer | Wirelessly transfer power over short ranges via magnetic fields; standard method for powering and triggering implanted electronic circuits. |

| Closed-Loop Feedback Controller [1] [13] | System Electronics | Processes real-time recorded biosignals to automatically adjust stimulation parameters; core component for adaptive, personalized therapy. |

| Bioresorbable Materials [14] | Device Framework | Create temporary implants that safely dissolve in the body after a therapeutic period; eliminate need for surgical extraction. |

| Autonomic Neurography [13] | Sensing/Monitoring | Precisely detects and titrates inflammatory immune responses via the autonomic nervous system; enables biomarker-driven neuromodulation. |

The historical evolution of electroceuticals demonstrates a clear trajectory from gross electrical application to precise, intelligent neuromodulation. When framed within the context of pharmaceutical outcomes research, the distinct value proposition of bioelectronic medicine lies in its target specificity, adaptability, and potential for reduced systemic side effects [1].

For researchers and drug development professionals, the future landscape presents several strategic imperatives. First, the convergence of miniaturized hardware, closed-loop sensing, and on-board artificial intelligence is creating devices that can fine-tune therapy dozens of times per second, opening the door to precision treatment for complex neurological and cardiovascular disorders [12]. Competitive differentiation will increasingly depend on algorithmic intelligence and reliable power management rather than production scale alone.

Second, the field is expanding beyond traditional neurological and cardiac indications into oncology, metabolic disorders, and autoimmune diseases [12]. For instance, Tumor Treating Fields have shown promise in disrupting cancer cell division, while targeted vagal modulation is being explored for inflammatory bowel disease [12]. This diversification offers new avenues for intervention where pharmaceuticals may have limitations.

Finally, the regulatory and reimbursement landscape is evolving. Regulatory agencies are streamlining breakthrough-device pathways, accelerating time-to-market for novel platforms [12]. Simultaneously, payers are shifting toward value-based contracts, favoring therapies that can document real-world outcome improvements and lower lifetime treatment costs compared to chronic drug regimens [12]. For the research community, this underscores the importance of generating robust clinical and health-economic data to support the adoption of next-generation electroceuticals as a pillar of 21st-century healthcare.

In the intricate landscape of disease pathways, two fundamental signaling modalities govern physiological processes and therapeutic interventions: chemical interactions and electrical signaling. Chemical transmission relies on molecular ligands—from small molecules to biologics—binding to cellular receptors to modulate biochemical pathways, forming the basis of most pharmaceutical interventions [18]. In contrast, electrical signaling operates through the movement of ions and changes in membrane potentials, enabling rapid communication within and between electrically excitable cells [19] [20]. The emerging field of bioelectronic medicine represents a paradigm shift, leveraging electrical signaling to modulate neural circuits that control organ function and disease processes, potentially offering alternatives to traditional pharmacotherapeutics [21] [22].

Understanding the distinct mechanisms, temporal profiles, and functional consequences of these communication modes provides critical insights for developing targeted therapeutic strategies. This comparison guide examines the fundamental principles, experimental approaches, and therapeutic applications of chemical and electrical signaling mechanisms in disease contexts, providing researchers with a framework for selecting and optimizing intervention strategies.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Biological Roles

Chemical Transmission Mechanisms

Chemical signaling operates through several distinct modalities with different spatial and temporal characteristics. Synaptic chemical transmission occurs at specialized junctions where neurotransmitters are released from presynaptic terminals into the synaptic cleft (typically 35-50 nm wide) and bind to receptors on the postsynaptic membrane [18]. This wiring transmission provides point-to-point communication with high privacy and safety, operating with a transmission delay in the millisecond range [18]. The concentration of chemical neurotransmitters in the synapse is typically high (micromolar range), with receptor affinities for endogenous neurotransmitters usually ranging from high nanomolar to micromolar [18].

Volume transmission represents a more diffuse chemical signaling mode where neurotransmitters and modulators diffuse through the extracellular fluid to reach remote target cells [19] [18]. This paracrine signaling operates over longer distances (seconds to minutes) and is characterized by transmitter-receptor mismatches at the anatomical level [18]. The extracellular space serves as the substrate for volume transmission, with specialized pathways along myelinated fiber bundles and blood vessels facilitating diffusion and flow [18].

Table 1: Characteristics of Chemical Signaling Modalities

| Feature | Synaptic Transmission | Volume Transmission |

|---|---|---|

| Velocity | Fast (milliseconds) | Slow (seconds to minutes) |

| Spatial Scale | Localized (synaptic cleft) | Diffuse (extracellular space) |

| Concentration | High (μM range) | Low (nM range) |

| Receptor Affinity | Low (high nM to μM) | High (low nM) |

| Divergence | Low | High |

| Safety | High | Low |

At the molecular level, chemical transmission involves complex cascades. Neurotransmitters bind to either ionotropic receptors (ligand-gated ion channels) that directly alter membrane potential, or metabotropic receptors (G-protein coupled receptors) that act indirectly through secondary messengers [19]. This allows chemical synapses to transform presynaptic signals through amplification and adaptation to diverse functional requirements [19].

Electrical Signaling Mechanisms

Electrical transmission occurs through two primary mechanisms. Electrical synapses are mediated by gap junctions—clusters of intercellular channels that directly connect the cytoplasm of adjacent cells [19] [23]. These gap junctions form low-resistance pathways that allow bidirectional passage of electrical currents and small molecules (up to 1-2 kDa) including ions, cAMP, IP₃, and calcium [19] [20]. Gap junction channels are formed by the docking of two hexameric connexin hemichannels (in vertebrates) or innexins (in invertebrates), with connexin 36 (Cx36) being the primary neuronal connexin in mammals [19].

Ephaptic transmission represents a distinct electrical signaling mode where synaptic currents generate electrical fields that can modulate chemical transmission in nearby neurons without direct physical contact [18]. This field effect coupling enables another layer of neuronal communication independent of both chemical synapses and gap junctions.

Electrical synapses are particularly efficient at detecting coincident subthreshold depolarizations within neuronal groups, promoting synchronous firing [19]. They also enable rapid signal transfer with minimal delay, making them particularly valuable in escape response networks across both invertebrates and vertebrates [19]. Unlike chemical transmission, electrical synapses operate in a bi-directional manner and do not require action potentials for analog signal transfer [19].

Table 2: Properties of Electrical Signaling Modalities

| Property | Electrical Synapses | Ephaptic Coupling |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Basis | Gap junctions | Extracellular electrical fields |

| Transmission Delay | Instantaneous | Instantaneous |

| Directionality | Bidirectional | Field-dependent |

| Signal Fidelity | High (analog) | Context-dependent |

| Molecular Transfer | Small molecules (<1-2 kDa) | None |

| Primary Function | Synchronization, rapid signaling | Modulation of excitability |

Integrated Signaling in Neural Systems

Rather than operating independently, chemical and electrical synapses functionally interact during both development and adult neural function [19]. Many synapses are "mixed," featuring both gap junctions and neurotransmitter release sites [20]. These interactions enable sophisticated computational capabilities that neither modality could achieve alone. For instance, electrical synapses can detect coincident activity necessary for strengthening specific chemical synaptic connections through Hebbian plasticity mechanisms [19].

The turn-over of gap junction channels is surprisingly dynamic, with half-lives estimated at 1-3 hours, allowing functional regulation of electrical coupling strength [19]. This dynamic regulation enables neural circuits to maintain flexibility in their computational properties, balancing the reliability of electrical synapses with the plasticity of chemical transmission.

Experimental Methodologies and Assessment Approaches

Investigating Chemical Signaling Pathways

Advanced techniques for profiling chemical signaling have evolved to capture complexity at single-cell resolution. Multiplexed Activity Profiling (MAP) combines phospho-specific flow cytometry with fluorescent cell barcoding to simultaneously measure multiple hallmark cellular functions in response to chemical perturbations [24]. This high-throughput approach enables deep structure-activity relationship studies (SAR-MAP) by quantifying bioactivity across numerous signaling nodes simultaneously.

A typical MAP experimental workflow involves:

- Cell Preparation and Barcoding: Cells are treated with compounds of interest and labeled with unique fluorescent dye signatures (FCB) [24]

- Fixation and Staining: Cells are fixed, permeabilized, and stained with fluorescent antibodies against phospho-proteins and functional markers [24]

- Flow Cytometry Acquisition: Multiparameter data is collected using modern cytometers capable of detecting 20+ parameters [24]

- Computational Analysis: Bioactivity is quantified using inverse hyperbolic sine fold changes in median fluorescence intensity versus vehicle controls [24]

Key measurable endpoints include:

- Apoptosis (cleaved CAS3)

- DNA damage response (γH2AX)

- Pathway activation (p-STAT3, p-STAT5, p-ERK, p-AKT, p-S6)

- Cell cycle status (p-HH3, Ki67)

- Membrane integrity (Ax700 uptake)

- Morphological parameters (forward/side scatter) [24]

For spatial control of chemical signal delivery, 3D-printed picoliter droplet networks enable patterned release of chemical inducers with ≈50 μm resolution [25]. These networks interface with cell populations through lipid bilayers containing engineered pores (α-hemolysin) that control molecular flux, allowing precise manipulation of gene expression patterns in underlying cells [25].

Assessing Electrical Signaling Function

Electrical signaling assessment requires specialized electrophysiological and imaging approaches. Paired intracellular recordings directly measure electrical synaptic strength by injecting current into one cell while recording voltage changes in coupled neighbors [19]. The coupling coefficient (postsynaptic/pre-synaptic voltage change) quantifies functional connectivity.

Gap junction permeability assays utilize fluorescent tracer molecules of different sizes (Lucifer yellow, neurobiotin) to assess molecular transfer between coupled cells [19]. This approach reveals both the presence and functional permeability of electrical synapses.

Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural techniques localize specific connexins using antibodies and visualize gap junctions at electron microscopic resolution [19] [23]. These morphological approaches provide anatomical correlates for functional electrical coupling.

Advanced approaches combine optogenetic control with electrophysiology to probe electrical synaptic function in complex networks. Transgenic animals expressing fluorescently tagged connexins (e.g., Cx36-GFP) enable visualization of electrical synapse distribution and dynamics in living tissue [19].

Diagram 1: Experimental assessment approaches for electrical and chemical signaling (47 characters)

Comparative Therapeutic Targeting in Disease Pathways

Pharmaceutical Targeting via Chemical Interactions

Small molecule therapeutics exert effects by structurally engaging biomolecular targets. Rocaglates, a class of translation inhibitors, exemplify structure-guided design where specific methoxy substitutions on pyrimidinone rings dictate anti-leukemia activity and cell-type selectivity [24]. Using SAR-MAP approaches, researchers identified that discrete structural features drive distinct bioactivity profiles in leukemia cells versus healthy leukocytes, enabling rational optimization of therapeutic indices [24].

Chemical therapeutics exhibit characteristic exposure-response relationships governed by:

- Target binding affinity (Kd values typically nM-μM)

- Pharmacokinetic parameters (Cmax, Tmax, AUC, half-life)

- Tissue penetration and metabolism

- Mechanism-based toxicity thresholds

The temporal dynamics of chemical interventions range from rapid receptor modulation (minutes) to chronic adaptive responses (days-weeks) involving transcriptional and translational changes [24]. This creates both opportunities for sustained effects and challenges from off-target accumulation.

Bioelectronic Interventions via Electrical Signaling

Bioelectronic medicine devices interface with neural circuits through several mechanism classes. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) modulates inflammatory reflexes by targeting specific fiber populations, reducing TNFα production in conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn's disease [22]. Deep brain stimulation (DBS) delivers targeted electrical currents to basal ganglia circuits, restoring movement control in Parkinson's disease by modulating pathological oscillations [21] [6]. Spinal cord stimulation (SCS) interferes with pain signal transmission, providing analgesia for chronic pain conditions [21] [6].

Modern bioelectronic systems increasingly feature closed-loop control where embedded sensors detect physiological states (e.g., seizure precursors) and trigger responsive stimulation, creating dynamic therapeutic adaptation [21] [6]. Advanced devices incorporate bidirectional communication, multimodal stimulation, and drug delivery capabilities [21].

Table 3: Therapeutic Applications of Electrical and Chemical Modalities

| Disease Area | Chemical/Pharmaceutical Approach | Bioelectronic/Electrical Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory Disorders | Anti-TNFα biologics (e.g., Humira), immunosuppressants | Vagus nerve stimulation to modulate inflammatory reflex [22] |

| Movement Disorders | Dopamine precursors (L-DOPA), dopamine agonists | Deep brain stimulation of basal ganglia [21] [6] |

| Chronic Pain | NSAIDs, opioids, gabapentinoids | Spinal cord stimulation [21] [6] |

| Cardiac Arrhythmias | Beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers | Implantable pacemakers, defibrillators [21] |

| Epilepsy | Anticonvulsants (e.g., valproate, levetiracetam) | Responsive neurostimulation, vagus nerve stimulation [21] |

Comparative Therapeutic Profiles

Electrical and chemical therapeutic modalities demonstrate distinct characteristic profiles. Precision and localization: Bioelectronic approaches can theoretically achieve greater spatial precision by targeting specific neural circuits, though current applications are limited to larger nerves [22]. Chemical approaches distribute systemically but can achieve cellular specificity through receptor expression patterns. Temporal control: Electrical stimulation offers millisecond-precision modulation with instantaneous onset/offset, while chemical effects develop over longer timescales with prolonged clearance kinetics [21] [22]. Adaptability: Closed-loop bioelectronics can dynamically adjust therapy based on physiological feedback, while chemical dosing typically follows fixed regimens [21]. Invasiveness: Bioelectronic approaches require surgical implantation with associated risks, while chemical administration is generally less invasive [22]. Reversibility: Electrical effects cease immediately upon stimulation termination, while chemical effects persist until clearance or metabolic inactivation [22].

Diagram 2: Therapeutic intervention mechanisms (34 characters)

Key Reagents and Research Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Signaling Studies

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Phospho-Specific Flow Cytometry | Multiplexed measurement of signaling pathway activation at single-cell resolution | Antibodies against p-STAT3, p-ERK, p-AKT, p-S6, c-CAS3, γH2AX [24] |

| Fluorescent Cell Barcoding (FCB) | Sample multiplexing for high-throughput signaling studies | Pacific Orange, Alexa Fluor dyes for sample multiplexing before antibody staining [24] |

| 3D-Printed Droplet Networks | Spatially patterned chemical signal delivery with micrometer resolution | Picoliter droplet networks with α-hemolysin pores for controlled inducer release [25] |

| Connexin-Specific Antibodies | Localization and quantification of gap junction proteins | Anti-Cx36 for neuronal electrical synapses, anti-Cx43 for astrocytic gap junctions [19] [23] |

| Tracer Molecules | Assessment of gap junction permeability | Neurobiotin, Lucifer Yellow, fluorescent dextrans of varying sizes [19] |

| Genetically Encoded Voltage Indicators | Optical monitoring of electrical activity | ASAP-family sensors, Archon indicators for all-optical electrophysiology |

| Microelectrode Arrays | Extracellular recording of network activity | Multielectrode arrays for in vitro and in vivo electrophysiology |

Experimental Model Systems

Different model systems offer complementary advantages for studying signaling mechanisms. Primary neuronal cultures enable reductionist investigation of synaptic mechanisms in controlled environments [19]. Acute brain slices maintain native circuitry while allowing precise pharmacological and electrophysiological manipulation [19]. In vivo animal models provide physiological context for assessing therapeutic interventions and network-level effects [22]. Human cell lines and organoids offer translational relevance for human-specific signaling mechanisms and therapeutic screening [24].

The choice of model system involves trade-offs between experimental control, throughput, and physiological relevance. Increasingly, researchers employ multiple complementary models to establish robust, translatable findings across biological scales.

Chemical interactions and electrical signaling represent complementary therapeutic paradigms with distinct mechanistic foundations and application landscapes. Chemical therapeutics leverage molecular recognition for selective target engagement, while bioelectronic approaches interface with endogenous neural circuits to modulate physiological processes. The optimal therapeutic strategy depends on multiple factors including disease pathophysiology, target accessibility, temporal requirements, and risk-benefit considerations.

Future progress will likely involve increased integration of these modalities, such as device-guided drug delivery systems and neuromodulatory small molecules. Advanced materials science enabling softer, more biocompatible interfaces will expand bioelectronic applications [6], while increasingly sophisticated chemical biology approaches will enhance specificity of pharmacological interventions [24]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding both chemical and electrical signaling mechanisms provides a more comprehensive toolkit for addressing diverse disease pathways and developing next-generation therapeutics.

The healthcare landscape is witnessing a pivotal transformation, moving from broad-spectrum pharmacological interventions to targeted, device-driven therapies. Bioelectronic medicine (BEM) represents this shift, using implantable or wearable electronic devices to interface with electrically active tissues—such as nerves, the heart, and the brain—to treat a wide array of diseases [21]. This approach modulates neural circuits to influence organ function, offering an alternative to systemic drugs. The convergence of an aging global population, a rising burden of chronic diseases, and rapid technological advancements is propelling the BEM market forward. This guide provides an objective comparison for researchers and drug development professionals, framing BEM within the broader context of therapeutic outcomes research compared to traditional pharmaceuticals.

Quantitative Market Driver Analysis

The expansion of the bioelectronic medicine market is quantitatively linked to three interdependent macro-trends. The data below summarizes key metrics and their direct impact on the BEM sector.

Table 1: Key Market Drivers and Quantitative Impact on Bioelectronic Medicine

| Market Driver | Key Quantitative Data | Direct Impact on BEM Market |

|---|---|---|

| Aging Global Population | • By 2030, 1.4 billion (1 in 6) people will be 60 or older [26].• By 2050, the population 80+ will triple to 426 million [26]. | Creates a larger patient base for age-related chronic conditions (e.g., arrhythmia, Parkinson's) treatable with BEM devices like pacemakers and deep brain stimulators [10] [21]. |

| Rising Chronic Disease Burden | • CVDs: Lead to ~17.9 million deaths annually [10].• Diabetes: Affected 537 million adults in 2021, projected to rise to 643 million by 2030 [10].• Pharmaceutical Consumption: Antidiabetic (+50%) and antidepressant (+40%) use rose sharply from 2013-2023 [27]. | Drives demand for non-pharmacological alternatives due to limitations of conventional drugs, including systemic side effects and variable patient response [21] [6]. |

| Technological Convergence | • AI & Digital Health: Enables real-time data analysis and personalized stimulation parameters [10] [28].• Materials Science: Soft, flexible electronics improve biocompatibility and long-term stability [6]. | Enhances BEM device efficacy, safety, and patient comfort, facilitating the development of closed-loop, adaptive systems [21] [29]. |

Comparative Therapeutic Outcomes: BEM vs. Pharmaceuticals

A core thesis in modern therapeutics research is the comparison between device-based and drug-based interventions. The following analysis contrasts their mechanisms, outcomes, and limitations across several key indications.

Table 2: Bioelectronic Medicine vs. Pharmaceutical Outcomes for Select Indications

| Disease / Indication | Bioelectronic Medicine (BEM) Approach | Reported BEM Outcomes & Challenges | Pharmaceutical Approach | Reported Pharmaceutical Outcomes & Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac Arrhythmia | Implantable Pacemaker / ICD: Provides electrical pulses to regulate heart rhythm [21]. | Efficacy: Established, life-saving gold standard for rhythm control [28].Challenges: Surgical implantation risk, device infection, lead failure [6]. | Antiarrhythmic Drugs (e.g., Amiodarone): Systemically modulate cardiac ion channels. | Efficacy: Effective for rhythm control in many patients [27].Challenges: Systemic side effects (e.g., thyroid, pulmonary toxicity); imperfect specificity [21]. |

| Parkinson's Disease & Essential Tremor | Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS): High-frequency stimulation of specific brain targets (e.g., STN) [21] [29]. | Efficacy: Reduces tremor, rigidity; improves motor function in select patients [29].Challenges: Invasive procedure; requires expert programming; device-related complications [6]. | Levodopa/Carbidopa: Oral precursor to dopamine to replenish depleted levels. | Efficacy: Highly effective for symptom control, especially initially.Challenges: Wearing-off effects, dyskinesias, and on-off fluctuations over time; non-physiological dopamine delivery [21]. |

| Type 2 Diabetes / Obesity | Research-Stage Neuromodulation: Vagus nerve stimulation to modulate metabolism/appetite [21] [28]. | Efficacy: An emerging area; aims for direct gut-brain axis modulation [28].Challenges: Primarily experimental; long-term efficacy and optimal parameters not yet defined. | GLP-1 Receptor Agonists (e.g., Semaglutide): Subcutaneous or oral drugs mimicking incretin hormones. | Efficacy: Powerful reduction in HbA1c and body weight [30].Challenges: High cost, high discontinuation rates (~50-70%) often due to GI side effects; requires chronic administration [30]. |

| Chronic Pain (e.g., Back Pain) | Spinal Cord Stimulation (SCS): Delivers low-voltage electrical stimulation to the spinal cord [21]. | Efficacy: Provides significant pain relief for many patients with failed back surgery syndrome [21].Challenges: Requires surgery, tolerance can develop, and device may require revision [6]. | Opioids (e.g., Oxycodone), NSAIDs: Systemically act on CNS and peripheral pain pathways. | Efficacy: Potent analgesia.Challenges: High risk of addiction, tolerance, and overdose with opioids; GI/renal/cardiovascular risks with chronic NSAID use [21]. |

| Drug-Resistant Depression | Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) / Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS): Invasive or non-invasive neuromodulation [29]. | Efficacy: VNS and TMS are FDA-approved for treatment-resistant cases, offering a durable response [29].Challenges: VNS is invasive; TMS requires repeated clinic visits; response can be delayed [29]. | SSRIs/SNRIs (e.g., Sertraline, Venlafaxine): Systemically increase monoamine levels in the brain. | Efficacy: First-line treatment, effective for many patients [27].Challenges: 30-40% of patients do not respond; side effects (e.g., sexual dysfunction, weight gain, nausea) lead to discontinuation [27]. |

Comparative Efficacy and Limitations Analysis

The data in Table 2 reveals distinct profiles. BEM often excels in providing targeted, reversible, and adjustable therapy for specific patient subsets, particularly those refractory to pharmacotherapy, with effects that are not dependent on systemic pharmacokinetics [21] [29]. Its limitations often involve invasiveness, upfront costs, and a defined set of device-related risks. Pharmaceuticals offer broad accessibility and non-invasiveness but are frequently limited by systemic side effects, imperfect target specificity, and adherence challenges stemming from both side effects and dosing regimens [21] [30]. The high discontinuation rates for chronic condition drugs like GLP-1s highlight a significant gap that BEM aims to address through its implantable, "always-on" therapeutic potential.

Experimental Protocols for BEM Device Validation

For researchers developing new BEM technologies, rigorous and standardized testing is paramount. The following protocols outline critical pathways for evaluating long-term device performance, a major focus of current R&D.

Protocol 1: Accelerated Life Testing for Implant Reliability

This protocol evaluates the mechanical and electrical longevity of implantable systems under simulated physiological conditions [6].

- Objective: To predict the functional lifespan and identify primary failure modes of a hermetic implantable pulse generator (IPG) or a flexible electrode array.

- Materials:

- Device Under Test (DUT): Sealed IPG or flexible electrode array.

- Saline Bath: Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at pH 7.4, maintained at 37°C.

- Environmental Chamber: For controlled temperature and humidity cycling.

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) Station.

- Mechanical Cyclers: For applying repetitive strain to flexible components.

- Methodology:

- Step 1: Perform baseline electrical characterization (impedance, stimulation output voltage/current).

- Step 2: Submerge DUT in a 37°C PBS bath, with options for:

- Static Soak: For assessing corrosion and fluid ingress.

- Accelerated Temperature/Humidity Cycling: (e.g., -20°C to +60°C, 90% RH) to induce thermo-mechanical stress.

- Step 3: For flexible implants, mount on a mechanical cycler to simulate in vivo movement (e.g., 100 million cycles at 1-2 Hz strain).

- Step 4: Periodically remove DUT for intermediate EIS and functional testing to monitor for performance drift or failure.

- Step 5: Upon failure or study conclusion, perform failure analysis (e.g., microscopic inspection, leak testing) to identify root cause.

- Outcome Measures: Mean Time Between Failures (MTBF), failure rate, specific failure modes (e.g., insulation breach, electrode corrosion, electronic malfunction) [6].

Protocol 2: In Vivo Biocompatibility and Functional Stability

This protocol assesses the foreign body response (FBR) and chronic performance of a BEM device in an animal model.

- Objective: To quantify the chronic tissue response and recording/stimulation stability of a novel soft neural interface.

- Materials:

- DUT: Soft, flexible electrode array (e.g., based on conducting polymers like PEDOT:PSS or polyimide substrates).

- Animal Model: Rodent or large animal model per IACUC protocol.

- Surgical equipment and stereotaxic frame.

- Histology Reagents: Paraformaldehyde (4%), cryostat, antibodies for immunohistochemistry (IHC: GFAP for astrocytes, Iba1 for microglia, NeuN for neurons), and appropriate fluorescent secondary antibodies.

- Neural recording and stimulation system.

- Methodology:

- Step 1: Aseptically implant the DUT into the target tissue (e.g., cortex, peripheral nerve).

- Step 2: Over a 12-week period, periodically measure:

- Electrical Performance: Electrode impedance, signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of recorded neural signals, stimulation charge injection limits.

- Step 3: At terminal time points, perfuse-fixate the animal and explant the tissue with the implanted device.

- Step 4: Process tissue for histology: section, and stain with H&E and IHC markers.

- Step 5: Image and quantitatively analyze the FBR: glial scar thickness, neuronal density around the implant, and extent of microglia activation compared to unimplanted control tissue [6].

- Outcome Measures: Glial scar thickness (µm), neuronal density (neurons/mm²), chronic impedance (kΩ), and SNR stability over time.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for BEM device validation, integrating in-vivo and ex-vivo protocols.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Developing and testing next-generation BEM devices requires a specialized suite of materials and reagents. The table below details key items critical for advancing the field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for BEM Development

| Item / Reagent | Category | Primary Function in BEM Research |

|---|---|---|

| Conducting Polymers (e.g., PEDOT:PSS) | Electrode Material | Bridges biology-electronics gap; improves charge injection, reduces impedance, enhances biocompatibility vs. metals [6]. |

| Flexible/Stretchable Substrates (e.g., Polyimide, PDMS) | Device Substrate | Provides soft, conformal interface with tissue; minimizes mechanical mismatch and chronic FBR [6]. |

| IHC Antibodies (GFAP, Iba1, NeuN) | Biological Reagent | Quantifies foreign body response and neuronal health around implants post-explantation [6]. |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | Laboratory Reagent | Simulates ionic body fluid environment for in-vitro accelerated aging and corrosion tests [6]. |

| Hermetic Encapsulation (e.g., SiC, Al2O3) | Packaging Material | Protects "dry" electronics from corrosive bodily fluids, ensuring long-term device functionality and biostability [21] [6]. |

| Wireless Power/Data Transfer Coils | System Component | Enables battery-less operation and communication with implanted devices, crucial for miniaturization [21]. |

The convergence of market drivers and technological innovation is setting the stage for the next generation of BEM. Key future directions include the development of closed-loop systems that use real-time biosensor data to automatically adjust therapy, truly realizing personalized medicine [29] [6]. Further, the expansion into new disease areas, particularly inflammatory and autoimmune disorders via the "neuro-immune axis," represents a frontier for non-drug intervention [29]. Finally, the push towards battery-less devices powered wirelessly and made from bioresorbable materials will address challenges related to device lifetime, surgical retrieval, and long-term environmental impact [21] [6].

For the research community, the comparison between bioelectronic and pharmaceutical outcomes is not about declaring a winner, but about defining the optimal therapeutic context for each. BEM offers a compelling, targeted, and adjustable modality for a range of chronic conditions, particularly where pharmaceuticals face challenges with specificity, adherence, or systemic toxicity. As the field overcomes hurdles related to device longevity, biocompatibility, and cost, its role as a complementary pillar to pharmacotherapy is poised to expand significantly, driven irrevocably by demographic shifts, chronic disease prevalence, and relentless technological convergence.

The Shift Towards Personalized, On-Demand Therapies and Reduced Environmental Impact

The healthcare landscape is undergoing a significant transformation, moving from a traditional one-size-fits-all model toward more tailored approaches. This guide objectively compares two distinct pathways in this evolution: bioelectronic medicine, which uses electrical signals to modulate nervous system activity, and pharmaceutical therapies, particularly those with personalized applications. The comparison examines their mechanisms, therapeutic outcomes, and environmental footprints to inform research and development strategies. Bioelectronic medicine represents a shift toward device-based, on-demand therapies that can be adjusted in real-time, while pharmaceutical outcomes research continues to evolve with more targeted biological agents. Understanding the distinctions between these approaches is crucial for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals navigating the future of therapeutic intervention.

Comparative Analysis: Mechanisms and Environmental Impact

Table 1: Direct Comparison of Bioelectronic Medicine and Pharmaceutical Therapies

| Comparison Parameter | Bioelectronic Medicine | Personalized Pharmaceuticals |

|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic Mechanism | Modulation of neural signals and specific nerve pathways [31] | Chemical interaction with molecular targets (e.g., receptors, enzymes) [32] |

| Personalization Approach | Programmable stimulation parameters; adaptive algorithms [28] [31] | Tailored to individual genetic, proteomic, or metabolic profiles [32] |

| Dosage/Application Control | On-demand, adjustable, and reversible stimulation [31] | Fixed-dose regimens based on patient characteristics [32] |

| Onset of Action | Typically rapid (milliseconds to seconds) | Variable (minutes to hours) |

| Environmental Impact (CO2e) | Device manufacturing and energy use [33] | High emissions from manufacturing, distribution, and supply chain [33] |

| Primary Waste Stream | Electronic waste (e-waste) from devices [33] | Pharmaceutical waste, single-use plastics, and lab waste [33] |

| Key Advantage | Non-pharmacological, avoids systemic side effects [31] | High specificity for molecular targets [32] |

| Key Limitation | Requires invasive procedures for implantable devices [31] | Environmental footprint from production and disposal [33] |

Table 2: Quantitative Environmental Impact Comparison

| Impact Category | Bioelectronic Medicine (Example Data) | Pharmaceuticals/Therapeutics (Example Data) |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Footprint (per course) | Data limited; device manufacturing and energy use contribute [33] | Radiotherapy (as proxy): 4,310 kg CO2e for 25-fraction course [34] |

| Contributing Factors | Patient transit, facility energy use, device manufacturing [33] | Patient transit, facility energy, medical supplies, manufacturing [34] |

| Waste Generation | E-waste from devices and components [33] | Significant plastic and medical waste [33] |

| Potential Mitigation | Hypofractionation, renewable energy, efficient devices [34] | Hypofractionation, sustainable packaging, waste recycling [33] [34] |

Experimental Data and Supporting Evidence

Bioelectronic Medicine Workflow and Outcomes

Experimental Protocol for Neuromodulation Therapy:

- Patient Selection: Identify patients with a confirmed diagnosis of a neuromodulation-responsive condition (e.g., drug-resistant epilepsy, Parkinson's tremor, chronic pain).

- Target Identification: Use imaging (MRI, CT) to anatomically locate the target nerve or brain region.

- Device Implantation: Surgically implant the bioelectronic device (e.g., vagus nerve stimulator, deep brain stimulation leads).

- Parameter Programming: Set initial electrical stimulation parameters (frequency, pulse width, amplitude) based on established protocols and individual patient anatomy.

- Dose Titration: Adjust stimulation parameters in a controlled setting to optimize efficacy and minimize side effects.

- Efficacy Assessment: Monitor therapeutic outcomes using standardized clinical scales (e.g., reduction in seizure frequency, improvement in tremor scores, pain scales).

- Long-term Follow-up: Assess device functionality, battery life, and long-term therapeutic maintenance [31].

Supporting Data: Studies on Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) show a median of 50% reduction in seizure frequency is achieved in a significant proportion of patients with drug-resistant epilepsy after 12 months of therapy, demonstrating a non-pharmacological option for a challenging patient population.

Pharmaceutical Outcomes and Personalized Approaches

Experimental Protocol for Targeted Drug Therapy:

- Biomarker Identification: Obtain patient biospecimen (tissue, blood) for genetic or proteomic analysis.

- Molecular Profiling: Sequence specific genes or assay protein levels to identify targetable mutations or biomarkers (e.g., EGFR in lung cancer, BRCA in breast cancer).

- Therapy Selection: Prescribe a pharmaceutical agent that specifically targets the identified molecular alteration.

- Dosing Regimen: Administer the drug according to a weight-based or fixed-dose schedule, as per clinical guidelines.

- Therapeutic Drug Monitoring: Measure drug levels in blood, if applicable, to ensure therapeutic range and avoid toxicity.

- Efficacy Assessment: Use radiographic imaging (e.g., RECIST criteria for oncology) and clinical evaluation to assess treatment response.

- Toxicity Monitoring: Record and manage drug-related adverse events [32].

Supporting Data: The use of Ivacaftor for cystic fibrosis patients with specific G551D mutations in the CFTR gene demonstrates the power of personalized pharmaceuticals. Clinical trials showed significant and sustained improvements in lung function (FEV1) compared to placebo, validating a genotype-driven treatment approach [32].

Visualization of Therapeutic Pathways

Diagram Title: Contrasting Therapeutic Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Investigative Studies

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-electrode Arrays | Record and stimulate electrical activity in neural tissues. | In vitro and in vivo studies of neurostimulation efficacy and safety [31]. |

| Biocompatible Encapsulants | Protect implanted electronics from the biological environment and ensure device longevity. | Development of chronic bioelectronic implants for human use [31]. |

| Genotyping Kits | Identify specific genetic variations in patient DNA samples. | Patient stratification for targeted drug trials and pharmacogenomic studies [32]. |

| Cytokine Assay Panels | Quantify protein biomarkers of inflammation and immune response. | Monitoring systemic effects of both neuromodulation and drug therapies [31]. |

| Target-Specific Antibodies | Detect and measure expression levels of protein targets. | Validation of target engagement in drug development and molecular diagnostics [32]. |

This comparison guide outlines a clear divergence in the mechanisms, applications, and environmental considerations of bioelectronic medicine and personalized pharmaceutical therapies. Bioelectronic medicine offers a unique value proposition with its on-demand, adjustable, and non-pharmacological mechanism of action, potentially leading to a different environmental impact profile centered on device manufacturing and energy use. In contrast, personalized pharmaceuticals provide exquisite molecular specificity but face challenges related to a significant environmental footprint from manufacturing and waste. For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice between these paradigms—or their potential convergence—will be guided by the disease target, the desired mode of action, and an increasing responsibility to consider environmental sustainability alongside therapeutic efficacy.

Therapeutic Applications and Technological Frontiers: From Pacemakers to Closed-Loop Systems

The management of cardiac arrhythmias represents a cornerstone of bioelectronic medicine, which harnesses implantable devices to interface with electrically active tissues, offering a therapeutic alternative to pharmacotherapies [1]. Unlike systemic drugs that can cause off-target effects, bioelectronic devices such as pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) provide precise, targeted treatment by directly modulating the heart's electrical system [6]. This approach has evolved significantly from the first fully implantable pacemaker in 1958 to sophisticated closed-loop systems that adapt to patient needs in real time [13]. Within the broader context of bioelectronic medicine versus pharmaceutical outcomes, these devices offer a compelling value proposition: they provide continuous, responsive therapy without the chemical side effects or variable pharmacokinetics associated with antiarrhythmic drugs, potentially revolutionizing care for patients with rhythm disorders [1].

Device Comparison: Pacemakers vs. Implantable Defibrillators

While both pacemakers and implantable defibrillators are crucial for arrhythmia management, they serve distinct functions and are indicated for different patient populations [35]. Understanding their complementary roles is essential for optimizing therapeutic strategy within a bioelectronic treatment paradigm.

Pacemakers are primarily designed to regulate slow or irregular heartbeats (bradycardia) by delivering low-energy electrical pulses to maintain a steady rhythm [35]. They continuously monitor the heart and provide stimulation only when the natural rhythm becomes too slow or pauses.

Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators (ICDs) serve a different purpose – they are specialized for terminating life-threatening rapid arrhythmias (tachycardia) such as ventricular tachycardia (VT) or ventricular fibrillation (VF) [36] [35]. These devices constantly monitor heart rhythms and deliver high-energy shocks to reset the heart to a normal rhythm when detected dangerous arrhythmias [35].

The table below summarizes the key differences between these device classes:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Pacemakers and Implantable Defibrillators

| Feature | Pacemakers | Implantable Defibrillators (ICDs) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Regulates slow heart rhythms [35] | Stops dangerous fast rhythms [35] |

| Energy Output | Low-energy pulses [35] | High-energy shocks [35] |

| Main Conditions Treated | Bradycardia, heart block, atrial fibrillation with slow ventricular response [35] | Ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, sudden cardiac arrest [35] |

| Patient Risk Profile | Moderate risk of fainting or fatigue from bradycardia [35] | High risk of sudden cardiac death [35] |

| Activation Mechanism | Continuously monitors and paces as needed [35] | Activates only during dangerous arrhythmias [35] |

| Battery Longevity | Typically 8-15 years [35] | Typically 5-10 years [35] |

| Therapeutic Paradigm | Chronic rhythm support | Emergency life-saving intervention |

Indications and Clinical Evidence

Device selection is guided by robust clinical evidence and appropriate use criteria established in recent guidelines [37].

Pacemaker Indications:

- Symptomatic bradycardia

- Advanced heart block

- Sinus node dysfunction

- Atrial fibrillation with prolonged pauses [35]

ICD Indications:

- Secondary Prevention: For patients who have survived sudden cardiac arrest due to VT/VF or experienced hemodynamically unstable VT [36]. Clinical trials including AVID, CASH, and CIDS demonstrated a 20-39% reduction in mortality with ICDs compared to antiarrhythmic drugs in this population [36].

- Primary Prevention: For patients with ischemic or nonischemic cardiomyopathy, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <35%, and New York Heart Association Class II/III symptoms on optimal guideline-directed medical therapy [36]. Landmark trials including MADIT, MADIT-II, and SCD-HeFT demonstrated significant mortality reduction with primary prevention ICDs [36].

Advanced ICD Technologies and Performance Data

The technological landscape of ICDs has evolved significantly, with current systems offering various configurations tailored to individual patient needs [36].

ICD System Architectures

Transvenous ICDs (TV-ICDs) represent the traditional approach with leads placed through the venous system into the heart [36]. These are further categorized by chamber configuration:

- Single-Chamber (SC) ICDs: One lead in the right ventricle [36]

- Dual-Chamber (DC) ICDs: Leads in both the right atrium and right ventricle [36]

- Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy Defibrillators (CRT-D): Leads in right atrium, right ventricle, and coronary sinus to synchronize ventricular contraction [36]

Subcutaneous ICDs (S-ICDs) feature a lead implanted just under the skin along the left side of the chest, without intravascular components, reducing certain procedural risks [36] [35].

Extravascular ICDs (EV-ICDs) represent the latest advancement, with leads placed outside the heart but within the chest, enabling antitachycardia pacing without transvenous leads [38].

Comparative Performance Data

Recent studies provide quantitative comparisons of ICD technologies and their performance:

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Contemporary ICD Technologies

| Technology | Inappropriate Shock Rates | Therapeutic Efficacy | Complication Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Chamber TV-ICD | Similar to DC-ICDs with modern discriminators [36] | APPRAISE ATP trial: 28% relative risk reduction in time to first all-cause shock with ATP enabled [38] | Lower rate of device-related complications compared to DC-ICDs without pacing indication [36] |

| Dual-Chamber TV-ICD | Historically lower, but contemporary studies show mixed results [36] | APPRAISE ATP trial: ATP success demonstrated in primary prevention [38] | Higher rate of pneumothorax, hemothorax, and lead dislodgement without pacing indication [36] |

| Subcutaneous ICD (S-ICD) | Comparable to transvenous systems with modern programming | MODULAR ATP: 61.3% ATP success rate when combined with leadless pacemaker [38] | Avoids lead-related cardiac complications; higher risk of pocket infections |

| ICD with Floating Atrial Dipole | Retrospective studies show modest reduction in inappropriate shocks [36] | Maintains single-chamber system simplicity while enabling better rhythm discrimination [36] | Similar to single-chamber systems; avoids additional lead complications |

MRI-Conditional ICDs represent another technological advancement, with the global market valued at approximately USD 1,750 million in 2025 and projected to reach USD 3,400 million by 2034, growing at a CAGR of 7.64% [39]. These devices incorporate special shielding and filters to safely undergo magnetic resonance imaging, addressing a significant limitation of earlier devices [39].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

APPRAISE ATP Trial Protocol

The Assessment of Primary Prevention Patients Receiving an ICD- Systematic Evaluation of ATP (APPRAISE ATP) study represents the largest head-to-head trial of antitachycardia pacing (ATP) in primary prevention patients with transvenous ICDs [38].

Objective: To evaluate the role of ATP by measuring time to first all-cause shock in primary prevention patients with TV-ICDs using contemporary programming [38].

Methodology:

- Study Design: Prospective, randomized controlled trial

- Population: Primary prevention patients with transvenous ICDs

- Intervention: Patients randomized to standard therapy (ATP and shock) versus shock-only treatment

- Primary Endpoint: Time to first all-cause shock

- Programming: Contemporary device programming protocols were utilized

- Follow-up: Regular device interrogation and remote monitoring

Key Findings:

- The ATP and shock arm demonstrated a 28% relative risk reduction in time to first all-cause shock

- This represents an absolute reduction in first all-cause shock in approximately 1% of primary prevention TV-ICD patients per year [38]

MODULAR ATP Clinical Trial Protocol

The MODULAR ATP trial evaluated the safety, performance, and effectiveness of a modular cardiac rhythm management system consisting of the EMBLEM S-ICD System and the EMPOWER Leadless Pacemaker [38].

Objective: To assess the first modular, intra-body, communicating subcutaneous defibrillator-leadless pacemaker system for tachycardia therapy [38].

Methodology:

- Study Design: Prospective clinical trial

- System Configuration: Modular system with S-ICD and leadless pacemaker components

- Communication Protocol: Intra-body communication between subcutaneous defibrillator and leadless pacemaker

- Primary Endpoints:

- Leadless pacemaker complication-free rate

- Communication success rate from S-ICD to leadless pacemaker

- Pacing capture thresholds

- ATP success rate

- Follow-up: Regular device interrogation and performance assessment

Key Findings:

- Leadless pacemaker complication-free rate of 97.5%

- Communication success rate of 98.8% from S-ICD to leadless pacemaker

- Low and stable pacing capture thresholds (≤2.0 V at 0.4 ms) in 97.4% of patients

- ATP success rate of 61.3%

- No patient requests for deactivation of ATP or bradycardia pacing due to pain or discomfort [38]

Research Reagent Solutions and Experimental Tools