Bioelectronic Medicine: The Emerging Frontier in Targeted Neuromodulation Therapies

This article explores bioelectronic medicine, an innovative field using targeted electrical signals to interface with the nervous system and treat disease.

Bioelectronic Medicine: The Emerging Frontier in Targeted Neuromodulation Therapies

Abstract

This article explores bioelectronic medicine, an innovative field using targeted electrical signals to interface with the nervous system and treat disease. It covers foundational principles from historical devices to next-generation closed-loop systems, examines therapeutic applications across neurology, cardiology, and immunology, addresses critical stability and reliability challenges for clinical translation, and provides comparative analysis against pharmacotherapies. For researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes technological advances, material innovations, and clinical validation shaping this rapidly evolving therapeutic paradigm.

From Ancient Shocks to Modern Implants: The Evolution of Bioelectric Therapy

Bioelectronic medicine is an emerging interdisciplinary field that uses electronic devices to interface with the body's electrically excitable tissues to treat diseases and restore function. This therapeutic approach represents a significant departure from conventional pharmacology, offering targeted neuromodulation with potentially fewer systemic side effects [1]. The conceptual foundations of bioelectronic medicine trace back to ancient observations of natural electrical phenomena in biological organisms, particularly electric fish, which demonstrated the profound connection between electricity and biological function long before modern understanding of electrophysiology [2] [1]. These early observations established a fundamental principle: that electrical signaling is an inherent property of biological systems that can be harnessed for therapeutic purposes.

The historical development of bioelectronic medicine reveals a fascinating trajectory from observation of natural electrical phenomena to sophisticated implantable devices. This evolution required convergence of multiple scientific disciplines including physiology, materials science, electrical engineering, and neuroscience [3]. The field has matured from simple electrical stimulation to complex bidirectional interfaces capable of both recording physiological signals and delivering targeted therapy, ultimately leading to the development of modern devices such as pacemakers, cochlear implants, and neural stimulators that form the foundation of contemporary bioelectronic medicine [1] [4].

Historical Timeline: Key Developments in Bioelectronic Medicine

Table 1: Historical Evolution of Bioelectronic Medicine

| Time Period | Key Development | Contributors/Examples | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2750-2500 BC | Therapeutic use of electric fish | Egyptian Fifth Dynasty | First documented use of biological electricity for pain management |

| 18th Century | Discovery of bioelectricity | Luigi Galvani (Italy) | Established fundamental connection between electricity and muscle contraction |

| Mid-18th Century | Electrostatic medical applications | Benjamin Franklin (USA), Kratzenstein (Germany) | Early attempts to apply man-made electricity therapeutically |

| 1840 | First clinical electrotherapy department | Dr. Golding Bird, Guy's Hospital (England) | Institutionalization of electrical therapies |

| 1958 | First fully implantable pacemaker | - | Revolutionized treatment of cardiac arrhythmias |

| 1961 | First cochlear implant | - | Restored hearing through electrical stimulation |

| 1970s | FDA recognition of TENS | United States Food and Drug Administration | Formal regulatory approval for transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation |

| 2000s | Advanced neuromodulation therapies | Vagus nerve stimulation for epilepsy and inflammation | Expanded applications to neurological and inflammatory conditions |

| 2024 | FDA approval for rheumatoid arthritis | SetPoint Medical's vagus nerve stimulator | First bioelectronic treatment approved for autoimmune disease [3] |

The historical timeline of bioelectronic medicine reveals a progressive understanding of electrical principles and their application to biological systems. Ancient civilizations utilized the powerful electrical discharges from torpedo fish (similar to electric eels) for pain relief, intuitively recognizing their therapeutic potential despite lacking scientific understanding of the underlying mechanisms [2] [1]. These early applications represented the first recorded instances of neurostimulation, establishing a foundation that would be built upon centuries later with more sophisticated technologies.

The 18th century marked a critical turning point with Luigi Galvani's seminal experiments demonstrating that electrical stimulation could induce muscular contractions in frog legs [1] [4]. This discovery of "animal electricity" provided the first experimental evidence for the electrical excitability of nervous tissue, fundamentally reshaping scientific understanding of neuromuscular physiology. Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, technological advances in generating and controlling electricity enabled more precise therapeutic applications, including the development of Galvanic, Faradic, and sinusoidal currents that became standard modalities in electrotherapy [2]. The mid-20th century breakthrough came with the development of fully implantable devices, beginning with cardiac pacemakers in 1958 and cochlear implants in 1961, which established the core principle of using implanted electronics to replace or modulate physiological functions [1].

Electric Fish: Nature's Blueprint for Bioelectronic Medicine

Electric fish represent remarkable natural models that demonstrate the evolutionary optimization of bioelectrical systems for sensing, communication, and defense. These organisms provided both the initial inspiration for bioelectronic medicine and continue to offer valuable insights into the principles of electrogenesis and neural control of electrical outputs. Two major groups of electric fish have been extensively studied: the strongly electric fish (such as the electric eel, Electrophorus electricus), capable of generating powerful discharges up to 600 volts for predation and defense, and weakly electric fish (including numerous species of South American knifefishes and African elephantfishes), which produce low-voltage signals for electrolocation and communication [5].

The neurophysiological mechanisms underlying electric organ function in these species reveal sophisticated biological solutions to electrical signal generation that have informed engineering approaches in bioelectronic medicine. Electric fish possess specialized electric organs derived from either muscle tissue (myogenic electric organs) or nervous tissue (neurogenic electric organs) [5]. These organs contain electrocytes – specialized cells that function similarly to neurons in generating action potentials but are optimized for producing external electrical fields rather than intracellular signaling [5]. In the electric eel (Electrophorus electricus), adults possess three distinct electric organs: the main organ, Sach's organ, and Hunter's organ, which collectively dominate the posterior 80% of the animal's body [5]. The sophisticated neural circuitry controlling these organs allows for precise modulation of discharge frequency and pattern, demonstrating nature's solution to the challenge of controlling bioelectrical outputs – a fundamental requirement for effective bioelectronic therapies.

Comparative Analysis of Electric Organs

Table 2: Electric Organ Types and Characteristics in Electric Fish

| Characteristic | Myogenic Electric Organ | Neurogenic Electric Organ |

|---|---|---|

| Tissue Origin | Muscle tissue | Nervous tissue |

| Electrocyte Type | Type A (within tail muscle) and Type B (below tail muscle) | Specialized neural tissue |

| Representative Species | Electrophorus electricus, Brachyhypopomus gauderio | Apteronotidae family (ghost knifefishes) |

| Discharge Properties | Monophasic, biphasic, or triphasic discharges | Continuous wave-type signals |

| Developmental Origin | Derived from muscle precursor cells | Derived from neural precursor cells |

| Key Proteins | Dystrophin, desmin, actin (muscle proteins) | Neural-specific proteins |

| Functional Specialization | Powerful discharges for predation/defense or weak signals for electrolocation | Primarily for electrolocation and communication |

The evolutionary convergence of electric organs across distantly related fish lineages demonstrates the fundamental advantage of electrical signaling in aquatic environments and provides nature's validation of electricity as a biological modality [5]. The anatomical structure of these organs, with electrocytes arranged in stacked columns and synchronized activation, represents a natural blueprint for designing efficient electrode arrays in bioelectronic devices. Furthermore, the precise neural control of electric organ discharges, which can be modulated by social context, reproductive state, and environmental factors, illustrates the principle of adaptive neuromodulation that underpins modern closed-loop bioelectronic systems [6] [5].

From Natural Principles to Clinical Applications: The Modern Era

The translation of principles from electric fish to human therapeutics required fundamental advances in understanding neural coding, bioelectrical phenomena, and device engineering. A critical milestone was the discovery of the inflammatory reflex by Kevin Tracey and colleagues, which revealed that the vagus nerve plays a central role in regulating immune function and inflammation [7]. This discovery provided a physiological basis for using electrical stimulation to treat inflammatory conditions, establishing a new paradigm for bioelectronic therapy beyond traditional neurological applications.

The modern era of bioelectronic medicine has been characterized by progressive technological miniaturization and increasing specificity of neural interfaces. Early implantable devices were relatively crude in their stimulation paradigms, delivering fixed patterns of electrical pulses without feedback from physiological states. Contemporary systems are evolving toward closed-loop architectures that continuously monitor physiological biomarkers and adjust stimulation parameters in real-time to maintain optimal therapy [1] [4]. This approach mirrors the adaptive control systems observed in electric fish, which modulate their electric organ discharges based on environmental context and behavioral requirements.

Current Clinical Applications and Market Landscape

Table 3: Modern Bioelectronic Medicine Applications and Market Data (2024)

| Application Area | Representative Devices | Key Conditions Treated | Market Value (2023) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac Rhythm Management | Implantable cardioverter defibrillators, cardiac pacemakers | Arrhythmia, heart failure | Largest segment of $23.54B market [8] |

| Neurological Disorders | Deep brain stimulators, vagus nerve stimulators | Parkinson's disease, tremor, epilepsy, depression | DBS: $1.41B; VNS: $479.15M [1] |

| Chronic Pain | Spinal cord stimulators, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulators | Neuropathic pain, failed back surgery syndrome | SCS: $2.92B [1] |

| Hearing Loss | Cochlear implants | Sensorineural hearing loss | Established therapy with continuous innovation |

| Inflammatory Diseases | Vagus nerve stimulators | Rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease | Emerging application with recent FDA approvals [3] |

The bioelectronic medicine market has experienced substantial growth, valued at USD 23.54 billion in 2024 and projected to reach USD 33.59 billion by 2030, representing a compound annual growth rate of 6.10% [8]. This expansion is driven by multiple factors including the rising prevalence of chronic diseases, technological advancements in device miniaturization and functionality, growing awareness of the limitations of pharmacological therapies, and an aging global population that increasingly requires chronic disease management solutions [8] [1]. The recent FDA approval of SetPoint Medical's vagus nerve stimulation device for rheumatoid arthritis marks a significant milestone, representing the first bioelectronic therapy approved specifically for an autoimmune condition and validating the concept of targeting neural circuits to modulate immune function [3].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

The advancement of bioelectronic medicine relies on sophisticated experimental methodologies that bridge multiple disciplines from basic neuroscience to device engineering. Fundamental to progress in the field is the ability to precisely interface with neural circuits and quantify the resulting physiological effects. The following experimental protocols represent core approaches that have enabled key discoveries in bioelectronic medicine.

Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) for Inflammatory Conditions

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of vagus nerve stimulation in modulating inflammatory responses and treating inflammatory diseases.

Background: The inflammatory reflex is a neural circuit that interfaces the immune and nervous systems, with the vagus nerve serving as the primary conduit for signals that regulate cytokine production and inflammation [7]. Electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve activates this pathway, resulting in suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF, IL-1β, and IL-6.

Materials and Reagents:

- Vagus Nerve Cuff Electrode: Multi-contact cuff electrode for selective vagus nerve stimulation

- Programmable Pulse Generator: Device capable of delivering precise current-controlled stimulation pulses

- Electrophysiology Recording System: For verifying neural activation and recording evoked potentials

- Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Kits: For quantifying cytokine levels (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) in serum and tissues

- Animal Model: Typically rodents or porcine models with induced inflammation (e.g., endotoxemia, rheumatoid arthritis)

- Microdissection Tools: For surgical exposure of the vagus nerve

- Histology Supplies: For verification of electrode placement and tissue response

Procedure:

- Surgically expose the cervical vagus nerve using aseptic technique

- Implant multi-contact cuff electrode around the vagus nerve

- Connect electrode to programmable pulse generator

- Apply stimulation parameters (typical settings: 0.5-2.0 mA, 100-500 μs pulse width, 10-30 Hz frequency)

- Monitor physiological parameters (heart rate, respiration) to ensure appropriate stimulation intensity

- Collect blood and tissue samples at predetermined time points for cytokine analysis

- Process samples using ELISA to quantify inflammatory mediators

- Sacrifice animals and perform histology to verify electrode placement and assess tissue response

Applications: This methodology has been successfully applied in preclinical models of rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, sepsis, and other inflammatory conditions, providing the foundation for clinical trials of VNS in these diseases [7].

Characterization of Electric Organ Physiology

Objective: To analyze the electrophysiological properties and discharge characteristics of electric organs in model species.

Background: Electric fish generate species-specific electric organ discharges (EODs) through the synchronized activity of electrocytes. Understanding the mechanisms of EOD generation and modulation provides insights into fundamental principles of bioelectrogenesis that can inform device design.

Materials and Reagents:

- Aquatic Electrophysiology Setup: Tank with calibrated electrode array for EOD recording

- High-Speed Voltage Recording System: Capable of sampling at ≥100 kHz to capture EOD waveform details

- Water Conductivity Meter: For standardizing experimental conditions

- Isolated Pulse Stimulator: For direct stimulation of electric organ efferent neurons

- Microelectrodes: For intracellular recording from electrocytes (as applicable)

- Pharmacological Agents: Neurotransmitter blockers (curare, atropine), ion channel modifiers (TTX, TEA)

Procedure:

- Acclimate fish in experimental tank with controlled water conductivity

- Position recording electrodes at standardized locations relative to the fish

- Record baseline EOD activity under various behavioral conditions (rest, exploration, social interaction)

- Analyze EOD waveform parameters: amplitude, duration, phase number, frequency spectrum

- For reduced preparations, directly stimulate efferent neurons to electric organ while recording output

- Apply pharmacological agents to characterize neurotransmitter systems and ion channels

- Use intracellular recording to analyze electrocyte membrane properties and action potential characteristics

- Correlate electrophysiological data with anatomical studies of electric organ structure

Applications: This approach has revealed fundamental mechanisms of pattern generation in neural circuits, the evolution of specialized electrogenic tissues, and principles of electrical field generation in biological tissues [6] [5].

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Technologies for Bioelectronic Medicine Research

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-Contact Cuff Electrodes | Selective stimulation and recording from peripheral nerves | Polyimide-based designs with 8-16 contacts for spatial selectivity [9] |

| Implantable Pulse Generators | Programmable electrical stimulation in chronic experiments | Bidirectional devices with sensing and stimulation capabilities [1] |

| Conducting Polymers | Improved electrode-tissue interface | PEDOT:PSS coatings reducing impedance and improving charge injection [1] |

| Wireless Telemetry Systems | Remote monitoring and control of implanted devices | Bluetooth Low Energy or medical implant communication service bands [1] |

| Computational Neural Models | Optimization of stimulation parameters and prediction of neural responses | ASCENT pipeline for simulating nerve responses to complex waveforms [9] |

| Flexible Bioelectronic Materials | Enhanced biocompatibility and reduced foreign body response | Stretchable electronics, hydrogels, liquid metal conductors [4] |

| Cytokine Assay Kits | Quantification of inflammatory mediators for immunomodulation studies | ELISA or multiplex bead arrays for TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 measurement [7] |

The development of increasingly sophisticated research tools has been instrumental in advancing bioelectronic medicine. Multi-contact cuff electrodes enable selective stimulation of specific nerve fascicles, dramatically improving the precision of neuromodulation therapies [9]. Computational models of nerve activation allow researchers to optimize stimulation paradigms in silico before validation in biological systems, accelerating the development of novel therapy approaches [9]. Advanced materials, particularly conducting polymers such as PEDOT:PSS, have significantly improved the interface between electronic devices and biological tissues by reducing impedance and enhancing charge transfer capacity [1]. These technological advances continue to push the boundaries of what is possible in bioelectronic medicine, enabling more precise, effective, and durable therapies.

Signaling Pathways and Neural Circuits

The therapeutic efficacy of bioelectronic medicine depends on precise interaction with specific neural pathways that regulate physiological processes. The inflammatory reflex represents one of the most thoroughly characterized neural circuits targeted by bioelectronic therapies.

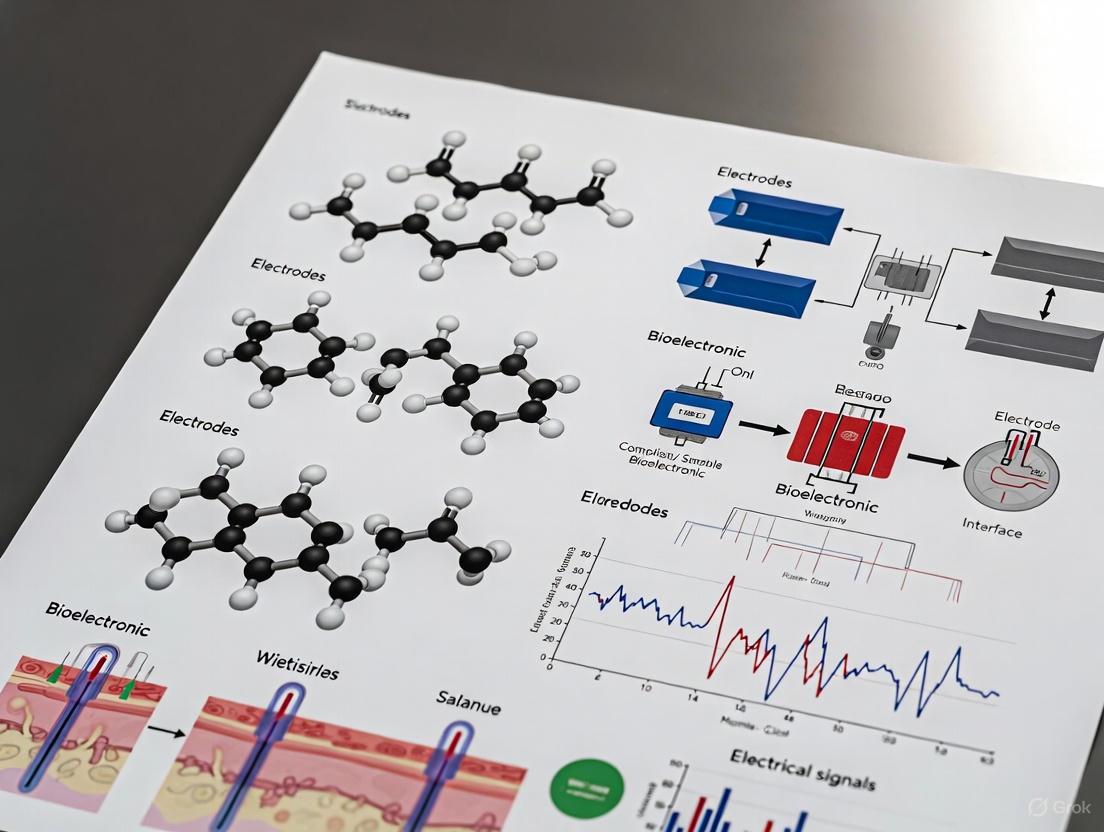

Figure 1: Neural Circuit of the Inflammatory Reflex. This diagram illustrates the neuroimmune pathway through which vagus nerve stimulation reduces inflammation. The circuit begins with peripheral inflammation detected by afferent vagus nerve fibers, integrates in the brainstem nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS), and activates efferent vagus nerve pathways that ultimately signal through the splenic nerve to trigger T-cell release of acetylcholine, which suppresses macrophage production of pro-inflammatory cytokines via α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (α7nAChR) [7].

The inflammatory reflex represents a sophisticated neural feedback system that maintains immunological homeostasis. Afferent vagus nerve signals carrying information about peripheral inflammation are integrated in the brainstem nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS), which then activates efferent vagus nerve pathways [7]. These efferent signals project to the celiac-superior mesenteric ganglion, where they activate the splenic nerve, which in turn triggers norepinephrine release in the spleen [7]. Norepinephrine stimulates a specialized population of T cells expressing choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) to produce acetylcholine, which acts on macrophages via α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors to inhibit the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [7]. This multi-synaptic pathway demonstrates the complex interplay between the nervous and immune systems that can be therapeutically targeted with bioelectronic devices.

Future Directions and Challenges

The field of bioelectronic medicine faces several significant challenges that must be addressed to realize its full potential. Device reliability and long-term stability remain critical concerns, particularly as implants become smaller and more complex [4]. The biological environment presents unique challenges for electronic devices, including mechanical stresses from constant movement, corrosion from bodily fluids, and the foreign body response that can insulate electrodes from their target tissues [1] [4]. These factors can compromise device performance over time and limit therapeutic efficacy.

Future advances in bioelectronic medicine will depend on interdisciplinary approaches that integrate developments in multiple fields. Materials science is producing a new generation of biocompatible, flexible, and even biodegradable electronic materials that better interface with biological tissues [1] [4]. Wireless power transfer technologies are enabling smaller, battery-free implants that can operate indefinitely without requiring surgical replacement [1]. Artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms are being integrated into closed-loop systems that can adapt therapy in real-time based on physiological feedback [8] [1]. These technological advances, combined with deepening understanding of neural circuit physiology, promise to expand the applications of bioelectronic medicine to a wider range of conditions including metabolic disorders, autoimmune diseases, and neurodegenerative conditions.

The historical foundation of bioelectronic medicine, from the early observations of electric fish to modern implantable devices, demonstrates a progressive understanding of the intimate connections between electrical signaling and biological function. As the field continues to evolve, it holds the potential to transform the treatment of chronic diseases through targeted neuromodulation, offering precisely controlled therapy with reduced side effects compared to conventional pharmacological approaches. The ongoing convergence of neuroscience, engineering, and materials science promises to accelerate this transformation, ultimately fulfilling the potential inherent in nature's earliest demonstrations of bioelectricity.

Bioelectronic medicine represents a paradigm shift in therapeutic strategies, moving from pharmaceutical compounds to the targeted modulation of neural circuits to treat disease. This field is grounded in the principle that the nervous system dynamically regulates physiological processes and organ functions through specific neural pathways. Dysregulation or pathology within these circuits can lead to a wide array of diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, cancer, diabetes, asthma, and cardiovascular conditions [3]. By mapping these circuits with high precision and developing technologies to neuromodulate their activity, researchers can develop interventions that restore healthy physiological states. This approach leverages the body's own innate control systems, offering the potential for highly specific, reversible, and adaptive treatments with fewer side effects than systemic drug administration [10].

The field is inherently interdisciplinary, integrating material science, biochemistry, biophysics, molecular medicine, neuroscience, immunology, bioengineering, electrical engineering, computer science, and artificial intelligence to decode and interface with the nervous system [3]. The ultimate focus is on understanding electrical signaling within the nervous system and developing technologies to record, stimulate, or block neural signals to affect specific molecular mechanisms. This spans from molecular-level interactions to circuit-level dynamics and whole-organism physiological outcomes, promising a new frontier in diagnosing and treating human disease [3].

Core Principles of Neural Circuit Function and Dysfunction

The functional architecture of the brain and peripheral nervous system is built upon specialized neural circuits, which are ensembles of interconnected neurons that process specific types of information and generate defined outputs. The central tenet of bioelectronic medicine is that these circuits form the structural basis for physiological control, and their dysfunction underlies numerous disease states. Several core principles govern how these circuits operate and how they can be targeted for therapeutic intervention.

Circuit Specificity and Connectional Logic: Neural circuits are not random networks but are organized with precise connectivity patterns that determine their function. The connectional logic dictates how information flows from inputs to outputs. For example, research on the retrosplenial cortex (RSC) has revealed that distinct projection pathways subserve different cognitive functions. Neurons projecting from the RSC to the secondary motor cortex (M2) are crucial for object-location memory and action planning, while those projecting to the anterodorsal thalamus (AD) are primarily involved in spatial memory [11]. This semi-autonomous operation of parallel pathways within a single brain region highlights the precision required for effective circuit-based interventions.

Excitatory-Inhibitory Balance: The dynamic interplay between excitatory and inhibitory neurons is fundamental to healthy neural circuit operation. Excitatory neurons, such as pyramidal cells, facilitate signal transmission, while diverse classes of inhibitory interneurons—including parvalbumin (Pvalb)-positive basket cells, somatostatin (SST)-positive Martinotti cells, and vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP)-positive bipolar cells—provide precise control over timing, synchronization, and network excitability [11]. Disruption of this delicate balance is implicated in numerous neurological and psychiatric conditions, including epilepsy, schizophrenia, and autism spectrum disorders [11].

Neuroplasticity and Circuit Remodeling: Neural circuits are not static but demonstrate neuroplasticity—the ability to strengthen, weaken, or reorganize synaptic connections in response to experience, learning, or injury. This capacity for change is central to both the pathogenesis of disease and the mechanism of therapeutic recovery. Following brain injury or in neurodegenerative diseases, promoting targeted neuroplasticity through neuromodulation or stem cell therapies represents a promising strategy for circuit repair and functional recovery [11]. Understanding the molecular and cellular mechanisms that govern this plasticity is therefore critical for developing effective bioelectronic therapies.

Hierarchy, Feedback, and Redundancy in Circuit Dynamics: The neural circuits governing fundamental processes like sleep and arousal operate on principles of feedback control, hierarchical organization, and functional redundancy. Computational models of the sleep-wake cycle have identified these three aspects as fundamental to the system's stability and function [12]. Feedback loops maintain state stability, hierarchical organization allows higher-order circuits to gate the activity of lower ones, and redundant pathways ensure robustness. Dysregulation in these dynamic properties can lead to state fragmentation, as seen in narcolepsy with dysfunction of the hypocretin (orexin) system [12].

Table 1: Key Neurotransmitter Systems in State-Dependent Neural Circuits

| Neurotransmitter | Primary Source Nuclei | Role in Circuit Function | Associated Pathologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypocretin (Orexin) | Lateral Hypothalamus | Controls boundaries between vigilance states, stabilizes wakefulness. | Narcolepsy, Cataplexy [12] |

| Norepinephrine (NE) | Locus Coeruleus | Promotes wakefulness and arousal; tonic activity during active wake. | Fragmented Sleep, Arousal Deficits [12] |

| Histamine (His) | Tuberomammillary Nucleus | Promotes wakefulness; diffuse projections throughout the brain. | Sleep Architecture Abnormalities [12] |

| Acetylcholine (ACh) | Basal Forebrain | Increased during wakefulness and REM sleep; critical for cortical activation. | Cognitive Impairment, Sleep Disorders [12] |

| Serotonin (5-HT) | Dorsal Raphe | Increased during wakefulness; modulates mood, arousal, and respiratory function. | Depression, Anxiety, Sleep Disorders [12] |

Methodologies for Neural Circuit Mapping and Analysis

A cornerstone of bioelectronic medicine is the ability to delineate the anatomical and functional organization of neural circuits with ever-increasing resolution and cell-type specificity. The methodologies for achieving this have evolved from gross lesion studies to sophisticated genetic and optical tools that allow for precise observation and manipulation of circuit components.

Anatomical Tracing Techniques

Anatomical tracing techniques reveal the "wiring diagram" of the brain by exploiting the natural axonal transport mechanisms of neurons.

Conventional Tracers: Early approaches used molecules like horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and fluorescent conjugates (e.g., Fluoro-Gold). These tracers are taken up by neurons and transported anterogradely (from soma to axon terminals) or retrogradely (from terminals back to the soma) to map efferent and afferent connections, respectively [13]. While useful, these methods often lack cell-type specificity.

Viral Vector-Based Tracers: Genetically modified viral vectors represent a revolutionary advance in circuit tracing. Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) are commonly used for anterograde tracing due to their safety and efficiency. For high-resolution mapping of direct inputs to a defined neuronal population, monosynaptic rabies virus systems are employed. This involves a two-part system: an initial "helper" AAV expresses the TVA receptor and rabies glycoprotein (G) in target cells, followed by a modified rabies virus (RV-ΔG) that lacks G and is pseudotyped with EnvA. This virus only infects TVA-expressing cells and, with the supplied G, undergoes a single, monosynaptic retrograde jump to directly presynaptic partners, allowing for input mapping at single-synapse resolution [11] [13].

Functional Manipulation and Interrogation

While anatomy provides the structural map, functional tools are required to establish causal links between circuit activity and physiological or behavioral outcomes.

Optogenetics: This technique provides millisecond-precision control over genetically defined neuronal populations. Neurons are made to express light-sensitive ion channels (e.g., Channelrhodopsin-2 for excitation, Halorhodopsin for inhibition). By delivering light via optical fibers, researchers can activate or silence specific circuits with high temporal precision, allowing them to probe the necessity and sufficiency of a circuit for a given function or behavior [11] [12]. For instance, optogenetic silencing of M2-projecting RSC neurons was shown to impair object-location memory [11].

Chemogenetics (DREADDs): Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs (DREADDs) offer an alternative for remote control of neural circuits. Engineered G-protein-coupled receptors are expressed in target neurons and activated by an inert ligand (e.g., Clozapine N-oxide). This allows for sustained modulation (over minutes to hours) of neuronal activity without the need for implanted hardware, making it suitable for studying longer-term processes like neuroplasticity or inflammation [11].

Nanostructured Photonic Probes: The integration of nanotechnology with neuroscience has led to the development of ultra-high-resolution probes. These devices combine tailored optogenetic stimulation with recording capabilities, offering spatial (~100 nm) and temporal (~ms) accuracy that surpasses traditional electrodes. This enables real-time observation and modification of brain activity at cellular and subcellular levels, opening new avenues for minimally invasive neurotherapeutic diagnostics and interventions [11].

Quantitative Modeling of Neural Circuit Dynamics

To translate the vast amounts of data from mapping and interrogation studies into predictive knowledge, the field increasingly relies on quantitative computational modeling. These models help interpret complex data, assist in optimizing experimental parameters, and drive the design of next-generation experiments and therapies [12].

Data-Driven Modeling with Artificial Neural Networks: A recent trend involves using artificial neural networks (ANNs) to create data-driven models that can quantitatively learn intracellular and circuit dynamics from experimental recordings. A key architecture is the Recurrent Mechanistic Model (RMM), which is formulated as a discrete-time state-space model [14]:

C(v̂_{t+1} - v̂_t)/δ = -h_θ(v̂_t, x_t) + u_t

x_{t+1} = f_η(v̂_t, x_t)

Here, v̂_t is the predicted membrane voltage, u_t is the injected current, x_t is a vector of internal state variables, C is a membrane capacitance matrix, and h_θ and f_η are learnable functions parameterized by ANNs. This approach can accurately predict unmeasured variables, such as synaptic currents within a circuit, from voltage measurements alone, providing a powerful tool for inferring internal connectivity [14].

System-Theoretic Modeling for State Transitions: For behaviors like sleep-to-wake transitions, analytical models can encapsulate the interactions between multiple neuromodulatory circuits. These models define the system components (e.g., Hcrt, NE, His systems) and mathematically represent their input-output relationships and interactions (e.g., feedback, redundancy, hierarchy). By fitting such models to empirical data, researchers can simulate system behavior under different conditions, propose limits on biological parameters, and identify key control points for intervention [12].

Training Methodologies for Predictive Models: The performance of data-driven models depends critically on the training algorithm. Empirical assessments compare methods like:

- Teacher Forcing (TF): Trains the model using the ground-truth voltage as input at each step.

- Multiple Shooting (MS): Divides the time series into segments and trains the model to match both the initial state and the dynamics of each segment, improving stability for long predictions.

- Generalized Teacher Forcing (GTF): A hybrid approach that uses ground-truth data for a limited number of steps before switching to the model's own predictions [14]. These methods enable the creation of stable and accurate models that can be used in real-time or closed-loop experimental paradigms.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Neural Circuit Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Primary Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|---|

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | Viral Vector | Gene delivery vehicle for expressing sensors, actuators, or tracing components in specific neuronal populations [11] [13]. |

| Monosynaptic Rabies Virus (RV-ΔG) | Viral Tracer | Retrograde tracer for mapping direct, monosynaptic inputs to a starter population of neurons [11] [13]. |

| Channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) | Optogenetic Actuator | Light-gated cation channel for precise millisecond-timescale activation of targeted neurons [11] [12]. |

| Designer Receptors (DREADDs) | Chemogenetic Tool | Chemically activated engineered GPCRs for remote, sustained modulation (minutes-hours) of neuronal activity [11]. |

| Tetracysteine Display of Optogenetic Elements (Tetro-DOpE) | Multifunctional Probe | A probe that allows for real-time monitoring and modification of specific neuronal populations, enhancing intervention precision [11]. |

| Recurrent Mechanistic Model (RMM) | Computational Model | A data-driven architecture (a type of Recurrent Neural Network) for rapidly estimating and predicting intracellular neuronal dynamics from voltage data [14]. |

Therapeutic Applications and Clinical Translation

The ultimate goal of mapping and modeling neural circuits is to develop novel, effective therapies for human disease. Bioelectronic medicine is already yielding clinically approved treatments and a robust pipeline of experimental therapies.

Inflammatory and Autoimmune Diseases: The most advanced success story is the FDA approval of a vagus nerve stimulation device from SetPoint Medical for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis [3]. This therapy is based on the pioneering scientific work that identified the inflammatory reflex—a specific circuit in which vagus nerve activity signals to the spleen to suppress the release of inflammatory cytokines like TNF [3]. This represents a paradigm of directly using a neural circuit to treat an inflammatory condition without broad immunosuppression.

Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders: Circuit-based interventions are showing great promise for a range of brain disorders.

- Depression and Anxiety: Non-invasive techniques like Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) are approved for treatment-resistant depression and are being investigated for anxious depression and OCD. TMS is thought to work by modulating activity in circuits linking the prefrontal cortex and amygdala, improving emotional regulation [11] [10].

- Substance Use Disorders (SUDs): Repetitive TMS (rTMS) targeting the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC)-amygdala circuit is being explored to improve emotional control and decision-making, thereby reducing impulsive drug-seeking behaviors [11].

- Stroke and Neurodegeneration: Strategies that combine stem cell therapies with neurogenesis-promoting interventions are under investigation to enhance circuit repair and functional recovery after brain injury [11].

The Future: Closed-Loop and Non-Invasive Systems: The next generation of bioelectronic medicine focuses on "closed-loop" systems that autonomously adjust therapy based on real-time physiological feedback. For example, a device paired with a biomarker sensor could titrate vagus nerve stimulation to maintain a desired level of inflammation or neural activity [10]. Furthermore, the development of non-invasive neuromodulation techniques (e.g., TMS) is a major priority, as it avoids the risks of surgery and increases the potential for widespread adoption and scale [10].

Table 3: Clinically Approved Bioelectronic Medicine Interventions

| Therapy / Device | Target Circuit / Structure | Primary Indication(s) | Key Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vagus Nerve Stimulation | Inflammatory Reflex (Vagus Nerve → Spleen) | Rheumatoid Arthritis [3] | Neuroimmunomodulation; suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines. |

| Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) | Subthalamic Nucleus, Globus Pallidus | Parkinson's Disease, Essential Tremor [10] | Modulation of pathological oscillatory activity in motor circuits. |

| Spinal Cord Stimulation (SCS) | Dorsal Columns of Spinal Cord | Chronic Pain, Motor Dysfunction from Injury [10] | Interference with pain signal transmission; activation of residual neural pathways. |

| Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) | Prefrontal Cortex, Amygdala Circuitry | Depression, OCD, Migraine Pain [11] [10] | Induction of currents in superficial brain regions to modulate circuit excitability and plasticity. |

The field of bioelectronic medicine is undergoing a fundamental transformation in its core material technologies. Traditional rigid implants are increasingly being replaced by soft, flexible bioelectronic devices that bridge the mechanical mismatch with biological tissues. This whitepaper examines the technological shift toward hydrogel-based semiconductors, detailing their manufacturing processes, experimental validation, and functional advantages. We provide a comprehensive technical analysis of material properties, experimental methodologies for characterizing tissue-integrated electronics, and a practical toolkit for researchers developing next-generation bioelectronic therapies. This paradigm shift enables more seamless biointerfaces for advanced neuromodulation, biosensing, and chronic implantation applications.

Bioelectronic medicine (BEM) represents a transformative approach to treating disease through electrical modulation of electrically active tissues, primarily the nervous system [1]. By interfacing with neural circuits that innervate every organ, bioelectronic devices can selectively target and modulate organ function, potentially replacing pharmacotherapies with precise, on-demand electrical stimulation [7] [1]. This field has evolved from early electrotherapy concepts to sophisticated implantable devices including spinal cord stimulators (SCS), deep brain stimulators (DBS), and vagus nerve stimulators (VNS) that treat conditions ranging from chronic pain and Parkinson's disease to drug-resistant epilepsy and inflammatory disorders [15].

Despite considerable clinical success, traditional bioelectronic implants face significant limitations stemming from their fundamental material properties. Conventional semiconductors are inherently rigid, brittle, and hydrophobic, creating a pronounced mechanical mismatch with soft, watery biological tissues [16]. This mismatch triggers foreign body reactions (FBR), inflammatory responses that form fibrotic tissue around implants, ultimately degrading device performance over time through reduced signal quality and increased impedance [1]. The encapsulation required to protect traditional electronics from bodily fluids further exacerbates these issues, creating additional bulk and rigidity [1].

The solution lies in developing bioelectronic interfaces with tissue-like mechanical properties - soft, stretchable, and highly hydrated materials that can deform harmoniously with surrounding tissue while maintaining robust electronic functionality [16]. This whitepaper examines the pioneering materials and methodologies driving this technological shift from rigid implants to soft, flexible bioelectronics.

Hydrogel Semiconductors: A Paradigm Shift in Biomaterial Design

Material Properties and Manufacturing Breakthrough

A groundbreaking advancement in soft bioelectronics comes from the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering, where researchers have created the first truly integrated hydrogel semiconductor [16]. This material represents a fundamental departure from previous approaches that merely attached conventional electronics to hydrogel substrates. Instead, the new material is both semiconductor and hydrogel simultaneously - a single integrated system with dual functionality [16].

The key innovation lies in a novel solvent exchange process that circumvents the traditional incompatibility between semiconductors and aqueous environments [16]. Rather than attempting to dissolve hydrophobic semiconductors in water, researchers first dissolved polymer semiconductors in an organic solvent miscible with water, then prepared a gel from the dissolved semiconductors and hydrogel precursors [16]. This methodology enables creation of a bluish, jelly-like material that maintains excellent semiconductive properties while achieving mechanical characteristics nearly identical to natural tissues.

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Traditional vs. Hydrogel Semiconductors

| Property | Traditional Semiconductors | Hydrogel Semiconductors |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Properties | Rigid, brittle | Soft, stretchable, tissue-like |

| Hydration | Hydrophobic (water-repelling) | Highly hydrated (water-loving) |

| Biocompatibility | High risk of foreign body reaction | Reduced immune response and inflammation |

| Porosity | Non-porous | Highly porous for molecular diffusion |

| Tissue Interface | Mechanical mismatch | Deforms harmoniously with tissue |

| Manufacturing Process | Standard microfabrication | Solvent exchange-based gelation |

Functional Advantages and Enhanced Biointeractivity

The unique material properties of hydrogel semiconductors translate to significant functional advantages in biological environments. The soft mechanical properties and high hydration similar to living tissue promote more intimate biointerfaces while reducing immune responses typically triggered by device implantation [16]. This enhanced biocompatibility is crucial for chronic implants that must function for 5-10 years without significant performance degradation [1].

The porous nature of hydrogel semiconductors enables elevated biosensing capabilities and stronger photomodulation effects [16]. Biomolecules can diffuse into the film, significantly increasing interaction sites for biomarkers and resulting in higher detection sensitivity. For therapeutic functions, such as light-operated pacemakers or wound dressings, the efficient transport of molecules enhances responses to light stimulation, potentially accelerating healing processes [16].

This combination of properties creates a synergistic effect where the integrated material system outperforms what either component could achieve separately - a "one plus one is greater than two" combination that represents a true paradigm shift in bioelectronic material design [16].

Experimental Characterization and Validation Methodologies

Mechanical and Electrical Property Assessment

Rigorous experimental characterization is essential to validate the performance of soft bioelectronic materials. The following methodologies provide comprehensive assessment of key material properties:

Mechanical Testing Protocol:

- Elastic modulus measurement: Perform uniaxial tensile testing using standardized specimens (e.g., 30mm × 10mm × 1mm) to determine Young's modulus under physiological strain rates (1-10% strain)

- Cyclic fatigue testing: Subject materials to repeated deformation cycles (typically 10,000+ cycles) at strains relevant to the target tissue (15-30% for peripheral nerves, 10-15% for brain tissue)

- Adhesion strength: Measure interfacial toughness between the hydrogel semiconductor and biological tissues using 90-degree peel tests or lap shear tests

Electrical Characterization Protocol:

- Impedance spectroscopy: Measure electrochemical impedance across frequency range 1 Hz-1 MHz using standard electrolyte solutions (e.g., PBS at 37°C)

- Charge storage capacity: Determine using cyclic voltammetry at physiologically relevant scan rates (1-100 mV/s)

- Stability assessment: Monitor electrical performance during continuous operation in simulated physiological conditions for extended durations (1000+ hours)

In Vitro and In Vivo Functional Validation

Beyond basic material properties, functional validation demonstrates practical efficacy in biological contexts:

In Vitro Biosensing Assessment:

- Sensitivity quantification: Immerse hydrogel semiconductor devices in solutions containing target biomarkers at physiological concentrations (e.g., cytokines, neurotransmitters)

- Selectivity testing: Evaluate response to interfering substances present in biological fluids

- Response time measurement: Monitor temporal response to sudden concentration changes

In Vivo Biocompatibility and Efficacy:

- Foreign body reaction assessment: Implant materials subcutaneously or in target neural tissues for 4-12 weeks, then histologically examine fibrotic capsule thickness, immune cell infiltration, and vascularization

- Functional efficacy: In disease models (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, epilepsy), compare therapeutic outcomes between hydrogel-based devices and traditional implants

- Chronic stability: Evaluate device performance and tissue response over extended periods (6+ months) relevant to clinical applications

Diagram 1: Experimental characterization workflow for soft bioelectronic materials, covering mechanical, electrical, and biological validation stages.

Design Principles for Next-Generation Soft Bioelectronics

Material Selection and Device Architecture

The design of soft bioelectronic devices requires careful consideration of multiple interrelated factors to achieve optimal performance in biological environments. Future bioelectronic systems are envisioned as distributed networks across three interweaved layers: the implant layer, an optional wearable companion layer, and a user interface layer for communication with patients, physicians, or cloud services [1].

Front-End Electrode Design: Modern neural interfaces are shifting from traditional metals to advanced materials that better bridge the biological-electronic divide. Conducting polymers have emerged as particularly promising candidates due to their mixed ionic/electronic conductivity, mechanical flexibility, and enhanced biocompatibility [1]. These materials offer reduced impedance compared to traditional electrodes, enabling further miniaturization that promotes treatment selectivity while reducing off-target effects [1]. Additional materials under investigation include graphene, MXenes, and carbon nanotubes, each offering unique electronic and optical properties beneficial for specific applications [1].

Device Encapsulation Strategies: Chronic implants require packaging that maintains functionality for 5-10 years in the harsh environment of the body [1]. Traditional approaches use hermetic packages to protect electronics from bodily fluids, but these are often rigid and create mechanical mismatch. Emerging strategies include:

- Thin-film encapsulation: Using multiple layers of biocompatible polymers and inorganic barriers

- Conformal coatings: Applying precise, pinhole-free coatings that accommodate device flexibility

- "Living electrode" concepts: Integrating cell layers into bioelectronic devices as functional interfaces that minimize biotic/abiotic mismatch [1]

Power and Data Management

Miniaturization and soft form factors introduce significant challenges for power delivery and data communication in implantable devices:

Wireless Power Transfer: Battery-less implants represent an important trend in soft bioelectronics, eliminating the need for battery replacement surgeries and facilitating device miniaturization [1]. Multiple wireless powering techniques are under development:

- Inductive/electrical transfer: Using coupled coils to transmit power through tissue

- Ultrasound-based powering: Employing piezoelectric materials to convert acoustic energy to electrical energy

- Magneto-electric and optical approaches: Emerging methods showing promise for specific applications

Data Communication Systems: The choice of communication systems involves careful trade-offs between local preprocessing and data transmission [1]. As implants become more sophisticated, some therapeutic approaches may require multiple implants that communicate and synchronize with each other [1]. This necessitates circuit designs that address multiple channels while providing efficient on-board processing capabilities. Neuromorphic circuits offer particularly promising approaches due to their power-efficient information processing properties suitable for edge computing paradigms at the implant level [1].

Table 2: Comparison of Wireless Power Transfer Methods for Soft Bioelectronics

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Suitable Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inductive Coupling | Magnetic field coupling between coils | High efficiency at short range, well-established technology | Rapid efficiency drop with distance, sensitive to misalignment | High-power applications (neural stimulators) |

| Ultrasonic Transfer | Piezoelectric conversion of acoustic waves | Better tissue penetration, less directional | Lower power density, potential tissue heating | Deep implants, distributed sensor networks |

| Optical Powering | Photovoltaic conversion of light | High power density, precise targeting | Limited tissue penetration, requires external light source | Subdermal implants, wearable integration |

| Magneto-Electric | Magnetic field to strain to voltage | Miniaturized receivers, medium penetration | Complex material systems, developing technology | Miniature implants, neural dust concepts |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Developing soft, flexible bioelectronics requires specialized materials and reagents that enable the creation of tissue-integrated electronic devices. The following toolkit outlines essential components for research in this emerging field:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Soft Bioelectronics Development

| Category | Specific Materials | Function/Purpose | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Semiconductor Polymers | DPP-based polymers, PEDOT:PSS, P3HT | Provide semiconductive properties in hydrated environment | Conjugated backbones, tailorable side chains, mixed conductivity |

| Hydrogel Matrix Materials | Polyacrylamide, Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate, Alginate, Gelatin methacrylate | Create hydrated, tissue-like mechanical environment | High water content, tunable modulus, biocompatibility |

| Conducting Polymers | PEDOT:PSS, PANI, PPy | Enable efficient ion-to-electron transduction at tissue interface | Mixed ionic/electronic conduction, mechanical flexibility |

| Crosslinking Agents | APS/TEMED, Irgacure 2959, LAP photoinitiators | Facilitate hydrogel formation and stability | Controlled gelation kinetics, biocompatible byproducts |

| Solvent Systems | DMSO, DMF, THF with aqueous mixtures | Enable solvent exchange processing | Water-miscible organic solvents with polymer solubility |

| Encapsulation Materials | Parylene-C, PDMS, SU-8, Silicon nitride | Protect electronic components from biological fluids | Conformal coating, barrier properties, mechanical compliance |

| Characterization Reagents | Potassium ferricyanide, PBS, synthetic interstitial fluid | Electrochemical and functional testing | Physiologically relevant ionic environment |

The technological shift from rigid implants to soft, flexible bioelectronics represents a fundamental advancement in bioelectronic medicine's core material science. Hydrogel semiconductors and other soft electronic materials bridge the mechanical mismatch between conventional electronics and biological tissues, enabling more intimate biointerfaces with reduced foreign body response. This paradigm shift, supported by novel manufacturing approaches like solvent exchange processing, facilitates devices that maintain excellent electronic functionality while achieving tissue-like mechanical properties.

Looking forward, several key challenges must be addressed to advance these technologies toward clinical application. Further material development is needed to enhance the stability and performance consistency of soft bioelectronic devices under chronic implantation conditions. Manufacturing processes must be scaled while maintaining precision and reproducibility. Regulatory frameworks need to adapt to these hybrid material systems that combine characteristics of medical devices, biologics, and drugs. Finally, standardized sterilization methods and implantation techniques must be developed specifically for these delicate, compliant devices.

The continued convergence of materials science, neural engineering, and molecular medicine will enable increasingly sophisticated bioelectronic therapies that seamlessly integrate with the nervous system. As these technologies mature, they promise to transform the treatment of chronic diseases through precise, personalized neuromodulation approaches that fundamentally improve upon both traditional pharmaceuticals and first-generation electronic implants.

Bioelectronic medicine represents a paradigm shift in therapeutic intervention, moving beyond pharmaceutical chemistry to use electrical signals for diagnosing and treating disease. This field leverages advanced neuromodulation technologies to interface with the nervous system, interpreting and manipulating neural signals to restore physiological balance. The foundational principle rests on understanding that the nervous system serves as the body's master communication network, continuously monitoring organ function and coordinating responses through precise electrical signaling. By targeting specific anatomical structures and neural pathways, bioelectronic devices can modulate everything from inflammatory responses to heart function, offering unprecedented precision in treating conditions as diverse as rheumatoid arthritis, epilepsy, depression, and inflammatory bowel disease [3] [10].

The therapeutic potential of bioelectronic medicine stems from the nervous system's inherent role as a biological interface that connects cognitive functions with peripheral physiology. This connection forms what researchers describe as the "brain–heart–immune axis," a communication network that enables centralized control over distributed bodily functions. Understanding the anatomical organization and functional specialization within this system provides the essential framework for developing targeted neuromodulation therapies that can achieve specific physiological outcomes with minimal side effects [17].

Core Neuroanatomy for Therapeutic Targeting

Central Nervous System Architecture

The central nervous system (CNS), comprising the brain and spinal cord, functions as the integrative command center for all neural processing. This system receives, processes, and responds to sensory information through highly specialized regions that can be selectively targeted for therapeutic modulation [18] [19].

Table 1: Major Central Nervous System Structures and Therapeutic Relevance

| Anatomical Structure | Primary Functions | Therapeutic Applications | Example Interventions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebral Cortex | Voluntary movement, cognition, sensory processing | Stroke recovery, chronic pain, movement disorders | Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), cortical implants |

| Thalamus | Sensory relay station, consciousness regulation | Chronic pain, disorders of consciousness | Deep brain stimulation (DBS) |

| Hypothalamus | Homeostasis, autonomic control, neuroendocrine function | Metabolic disorders, sleep disorders, hypertension | Focused ultrasound, implantable stimulators |

| Brainstem | Cardiorespiratory control, consciousness, cranial nerve functions | Epilepsy, depression, migraine, respiratory control | Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), respiratory pacemakers |

| Cerebellum | Motor coordination, balance, motor learning | Movement disorders, tremor, ataxia | Cerebellar stimulation, non-invasive modulation |

| Spinal Cord | Sensorimotor relay, reflex integration | Paralysis, chronic pain, bladder control | Spinal cord stimulation (SCS), intraspinal interfaces |

| Limbic System | Emotion, memory, motivation | Depression, PTSD, addiction | Deep brain stimulation, responsive neurostimulation |

The cerebral cortex represents the most evolved region of the human brain, with different lobes specializing in distinct functions. The frontal lobe enables voluntary motor control and executive functions, the parietal lobe processes somatosensory information, the temporal lobe manages auditory processing and memory, and the occipital lobe specializes in visual processing. Each of these regions offers unique targeting opportunities for conditions ranging from stroke recovery to neuropsychiatric disorders [18].

Deeper brain structures provide additional critical targets. The thalamus serves as the central relay station for sensory information, making it ideal for pain management interventions. The hypothalamus, despite its small size, regulates fundamental processes including heart rate, blood pressure, appetite, and hormonal release through connections with the pituitary gland. The brainstem houses essential autonomic centers controlling respiration, cardiovascular function, and consciousness, while the cerebellum fine-tunes motor commands to ensure smooth, coordinated movements [18].

The spinal cord forms the final common pathway for CNS output, containing both ascending sensory pathways and descending motor pathways. This organization creates opportunities for interventions at multiple levels to restore function after injury or disease. The recent development of non-invasive spinal cord stimulation techniques has shown promise for addressing urinary dysfunction, bowel control, and sexual function following cervical spinal cord injury [17].

Peripheral Nervous System Pathways

The peripheral nervous system (PNS) connects the CNS to organs, limbs, and skin, creating the communication network that enables whole-body integration. The PNS is functionally divided into the somatic nervous system (mediating voluntary movements) and the autonomic nervous system (regulating involuntary physiological processes) [19].

The autonomic nervous system represents a particularly valuable target for bioelectronic medicine, as it controls visceral functions that are frequently disrupted in chronic disease. This system is further subdivided into sympathetic ("fight-or-flight") and parasympathetic ("rest-and-digest") branches, which generally exert opposing effects on target organs. The vagus nerve, as the primary parasympathetic nerve, has emerged as a particularly promising target given its extensive innervation of thoracic and abdominal organs and its fundamental role in regulating inflammation, heart rate, and gastrointestinal function [10] [17].

Table 2: Key Peripheral Nerves for Bioelectronic Intervention

| Nerve/Target | Innervation | Physiological Influence | Clinical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vagus Nerve | Heart, lungs, digestive tract, liver, spleen | Heart rate reduction, inflammation control, gastric motility | Rheumatoid arthritis, epilepsy, depression, inflammatory bowel disease |

| Spinal Nerves | Limbs, trunk, neck | Motor control, sensory feedback | Chronic pain, motor rehabilitation, peripheral nerve injury |

| Splanchnic Nerves | Abdominal viscera | Gastrointestinal function, visceral sensation | Irritable bowel syndrome, visceral pain |

| Sacral Nerves | Bladder, bowel, reproductive organs | Urination, defecation, sexual function | Incontinence, bladder dysfunction, fecal incontinence |

Recent advances have demonstrated that the autonomic nervous system provides a precise communication pathway between the brain and peripheral immune function. This "neuro-immune axis" enables neural modulation of inflammation, creating opportunities for treating conditions like rheumatoid arthritis through vagus nerve stimulation rather than immunosuppressive drugs. The recent FDA approval of SetPoint Medical's vagus nerve stimulation device for rheumatoid arthritis represents a landmark validation of this approach [3] [10].

Molecular Signaling and Neurotransmitter Systems

Key Neurotransmitter Pathways

Neurotransmitters serve as the chemical messengers of neural communication, converting electrical signals into chemical signals at synapses throughout the nervous system. These molecules represent critical intervention points for both pharmacological and bioelectronic approaches, as their balance directly influences neuronal excitability, information processing, and ultimately physiological outcomes [20].

Table 3: Major Neurotransmitter Systems and Modulation Strategies

| Neurotransmitter | Primary Action | Receptor Types | Role in Disease | Modulation Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glutamate | Primary excitatory neurotransmitter | NMDA, AMPA, kainate, metabotropic | Excitotoxicity in stroke, Alzheimer's, ALS | Receptor antagonists, release modulation |

| GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid) | Primary inhibitory neurotransmitter | GABAA (ionotropic), GABAB (metabotropic) | Epilepsy, anxiety, insomnia | Receptor agonists, reuptake inhibitors |

| Acetylcholine | Autonomic control, neuromuscular junction | Nicotinic, muscarinic | Myasthenia gravis, Alzheimer's, autonomic dysfunction | Receptor agonists/antagonists, cholinesterase inhibitors |

| Norepinephrine | Sympathetic nervous system activation | α1, α2, β1, β2-adrenergic | Depression, anxiety, hypertension | Reuptake inhibitors, receptor blockers |

| Dopamine | Motor control, reward, motivation | D1-D5 receptors | Parkinson's disease, schizophrenia, addiction | Receptor agonists, precursor supplementation |

| Serotonin | Mood, appetite, sleep | 5-HT1-7 receptors | Depression, anxiety, migraine | Reuptake inhibitors, receptor agonists |

Glutamate serves as the predominant excitatory neurotransmitter in the CNS, playing essential roles in synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory. However, excessive glutamate release can lead to excitotoxicity, a process implicated in various neurological conditions including stroke, epilepsy, and neurodegenerative diseases. The balance between glutamate and GABA, the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter, determines neuronal network stability and represents a crucial target for maintaining neural homeostasis [20].

The cholinergic system, centered around acetylcholine, deserves particular attention in bioelectronic medicine due to its fundamental role in the "inflammatory reflex"—a neural circuit through which the vagus nerve regulates immune function. Vagus nerve stimulation activates cholinergic signaling that suppresses pro-inflammatory cytokine release, providing a mechanistic explanation for the anti-inflammatory effects observed in conditions like rheumatoid arthritis [3] [17].

Signaling Pathways in Neural Circuits

The therapeutic effects of neuromodulation emerge from precisely altering activity in specific neural circuits. Understanding these circuits at both the anatomical and molecular levels enables increasingly targeted interventions.

Diagram 1: Neuro-Immune Signaling Circuit

The diagram above illustrates the inflammatory reflex circuit, a well-characterized neural pathway that connects peripheral inflammation to brain-mediated responses through the vagus nerve. This circuit begins with sensory neurons detecting inflammatory cytokines, relaying this information to CNS integration centers, which in turn activate autonomic output through the vagus nerve to suppress inflammation via cholinergic signaling to immune cells [3] [17].

Experimental Methodologies and Technical Approaches

Neural Interface Technologies

Advanced neural interfaces form the technological foundation of bioelectronic medicine, enabling precise recording and modulation of neural activity. These interfaces vary significantly in their invasiveness, spatial resolution, and target applications.

Table 4: Neural Interface Modalities and Characteristics

| Interface Type | Invasiveness | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-invasive (tDCS, TMS) | Non-invasive | Low (cm) | Medium (ms) | Depression, chronic pain, stroke rehabilitation |

| Transcutaneous (tVNS, tsFUS) | Minimally invasive | Medium (mm-cm) | High (μs-ms) | Inflammation control, epilepsy, metabolic disorders |

| Peripheral Nerve Interfaces | Surgical implantation | High (μm-mm) | High (μs-ms) | Rheumatoid arthritis, IBD, blood pressure control |

| Spinal Cord Stimulators | Surgical implantation | Medium (mm) | High (μs-ms) | Chronic pain, spasticity, bladder control |

| Deep Brain Stimulators | Surgical implantation | High (μm-mm) | High (μs-ms) | Parkinson's disease, epilepsy, depression |

Non-invasive techniques like transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) modulate cortical excitability through external application of electrical currents or magnetic fields. These approaches offer the advantage of minimal risk but provide relatively limited spatial resolution and depth penetration. Recent innovations in temporal interference (TI) stimulation have enabled non-invasive targeting of deeper brain structures by using multiple high-frequency fields that interfere to create a net stimulation effect only at their intersection point [10] [17].

Implantable interfaces provide superior specificity and access to deeper neural targets but require surgical intervention. The development of closed-loop systems represents a particularly promising advance, as these devices can continuously monitor physiological or neural biomarkers and automatically adjust stimulation parameters in response. This creates self-regulating therapeutic systems that can adapt to changing patient needs in real time [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 5: Key Research Reagents for Neural Circuit Investigation

| Reagent/Material | Category | Research Application | Experimental Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Channelrhodopsins (ChR2) | Optogenetic actuator | Neural circuit mapping | Light-activated cation channel for neuronal excitation |

| Halorhodopsins (NpHR) | Optogenetic inhibitor | Neural circuit manipulation | Light-activated chloride pump for neuronal inhibition |

| AAV vectors | Viral delivery tool | Targeted gene delivery | Neuron-specific transduction for optogenetic/chemogenetic manipulation |

| DREADDs | Chemogenetic tool | Remote neural control | Designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs |

| Neurotransmitter sensors (iGluSnFR, dLight) | Molecular sensor | Neurotransmitter release monitoring | Genetically encoded fluorescent indicators of neurotransmitter dynamics |

| Multielectrode arrays | Electrophysiology tool | Neural population recording | High-density recording of extracellular neuronal activity |

| Carbon fiber electrodes | Neural interface | In vivo electrophysiology | Single-unit recording and stimulation in behaving animals |

| Neurotrophic factors (BDNF, NGF) | Biological response modifier | Neural plasticity studies | Enhancement of neuronal survival, growth, and synaptic plasticity |

The experimental workflow for investigating and validating neural targets typically begins with molecular tools for circuit mapping, progresses through physiological recording and manipulation, and culminates in behavioral or therapeutic outcome assessment. Optogenetics has revolutionized neural circuit dissection by enabling millisecond-precise control of genetically defined neuronal populations, while chemogenetic approaches like DREADDs (Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs) offer remote neuronal manipulation over longer timescales without implanted hardware [21].

Advanced electrophysiological systems provide critical readouts of neural activity, with high-density multielectrode arrays enabling simultaneous recording from hundreds of neurons. These tools are essential for deciphering the neural codes that represent sensory information, motor commands, and pathological states. The development of miniaturized, wireless recording systems has further enabled the study of naturalistic behaviors without movement constraints [17].

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Target Development

The experimental workflow for target development follows a logical progression from basic anatomical identification through clinical translation. Each stage builds upon findings from the previous one, with continuous refinement of both biological understanding and technological capabilities. This iterative process ensures that therapeutic interventions are grounded in rigorous mechanistic understanding while meeting practical clinical requirements [21] [10] [17].

Emerging Frontiers and Future Directions

The field of bioelectronic medicine continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging frontiers promising to expand therapeutic capabilities. Non-invasive neuromodulation approaches represent a particularly promising direction, as they eliminate surgical risks and can be more readily scaled for widespread clinical use. The combination of non-invasive techniques with closed-loop control systems creates opportunities for adaptive therapies that continuously optimize treatment parameters based on real-time physiological feedback [10].

Another significant frontier involves the development of pathogen-specific neuromodulation strategies. Research has revealed that the body produces unique neural response patterns to different infectious agents over time. Creating a "pathogen library" of these signature responses could enable precise identification of infectious agents and guide targeted neuromodulation interventions to impede pathogen-specific inflammatory cascades. This approach could revolutionize the management of infectious diseases and sepsis [10].

Bioelectronic approaches also show exceptional promise for addressing mental health disorders through modulation of the neuro-immune axis. Conditions including post-traumatic stress disorder, major depression, and anxiety disorders have been linked to inflammatory processes and vagus nerve pathology. The emerging ability to assess brain inflammation through techniques like autonomic neurography may enable objective stratification of mental health severity and guide precise neuromodulation treatments tailored to individual neuro-immune profiles [10].

The convergence of bioelectronic medicine with artificial intelligence and machine learning is already yielding sophisticated approaches for treatment personalization. Recent studies have demonstrated that machine learning algorithms can optimize non-invasive brain stimulation parameters for major depression and predict individual treatment responses. These computational approaches leverage high-dimensional physiological data to identify biomarkers that guide therapy selection and parameter optimization, moving beyond the traditional one-size-fits-all approach to neuromodulation [17].

As the field advances, the integration of increasingly sophisticated biological understanding with cutting-edge engineering innovations promises to unlock new therapeutic possibilities across a broad spectrum of diseases. The ongoing refinement of neural interfaces, combined with deeper insights into neural circuit function and pathology, positions bioelectronic medicine as a transformative approach that harnesses the body's inherent communication systems for precise, adaptive therapeutic intervention.

Bioelectronic medicine represents a transformative frontier in therapeutic science, founded on the interdisciplinary convergence of neuroscience, materials science, and microelectronics. This field utilizes advanced technological devices to interface with the electrically active nervous system to diagnose and treat diseases, offering a paradigm shift from conventional pharmacotherapies [1]. By establishing direct communication pathways with neural circuits, bioelectronic medicine promises targeted, personalized treatments with reduced off-target effects for conditions ranging from inflammatory diseases and metabolic disorders to paralysis and mental health conditions [3] [7] [10]. The foundational principle hinges on decoding the language of the nervous system—electrical and chemical signals—and developing sophisticated interfaces to modulate these signals with precision. This convergence has accelerated dramatically in recent years, driven by simultaneous advances in neural circuit mapping, flexible electronics manufacturing, and miniature implanted systems capable of closed-loop operation [22] [1].

The therapeutic potential of bioelectronic medicine is vast. The nervous system maintains homeostasis and health through complex reflex circuits that control involuntary processes, including immune function, inflammation, cardiovascular regulation, and metabolism [7]. Homeostatic disruptions underlying numerous diseases can be controlled by bioelectronic devices targeting central and peripheral neural circuits [7]. For instance, the inflammatory reflex—a neural circuit mediated by the vagus nerve that regulates immune function and inflammation—can be modulated using bioelectronic vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) to suppress excessive pro-inflammatory cytokine release and alleviate deleterious inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and other chronic inflammatory conditions [3] [7]. The growing clinical translation of these approaches is evidenced by recent FDA approvals of bioelectronic devices for autoimmune diseases and the expanding markets for spinal cord stimulation, deep brain stimulation, and vagus nerve stimulation technologies [1].

Foundational Scientific Principles

Neural Signaling and Circuit Mechanisms

The nervous system functions through intricate networks of electrical and chemical signaling that maintain physiological homeostasis. Billions of neurons collectively form neural networks, transmitting information via electrophysiological signals (action potentials) and neurochemical messengers (neurotransmitters) to facilitate essential biological activities, including perception, learning, memory, and autonomic functions [22]. These signaling mechanisms enable the nervous system to regulate virtually every organ and physiological process in the body, forming the basis for bioelectronic interventions [7].