Biocompatibility Testing for Organic Electronic Materials: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Developers

This article provides a thorough examination of biocompatibility testing specifically for organic electronic materials, which are pivotal for the next generation of implantable and wearable medical devices.

Biocompatibility Testing for Organic Electronic Materials: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Developers

Abstract

This article provides a thorough examination of biocompatibility testing specifically for organic electronic materials, which are pivotal for the next generation of implantable and wearable medical devices. It covers the foundational principles that make these materials—such as conjugated polymers and biocompatible elastomers—uniquely suited for biointegration, detailing their mechanical and charge transport properties. The scope extends to established and emerging testing methodologies aligned with ISO 10993 standards, strategies for troubleshooting common challenges like inflammatory responses and material degradation, and the critical processes for in vitro and in vivo validation. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and development professionals, this guide synthesizes current research, innovative testing platforms, and real-world case studies to navigate the path from material design to clinically safe bioelectronic devices.

The Fundamentals of Organic Electronic Materials and Biocompatibility

Defining Biocompatibility in the Context of Medical Devices and ISO Standards

Biocompatibility is defined as the "ability of a medical device or material to perform with an appropriate host response in a specific application" [1]. It is not an intrinsic property of a material but a conditional one, heavily dependent on the device's intended use and the nature of its interaction with the body [2]. The evaluation of biocompatibility is a critical pillar in the development of any medical device, ensuring that devices which contact patients—from simple surgical masks to complex implantable sensors—do not cause unacceptable adverse biological reactions [3] [4].

The international benchmark for managing biological risk is the ISO 10993 series of standards, titled "Biological evaluation of medical devices" [3] [1]. This series provides a consistent, science-based framework for biological safety evaluations, used by regulators, notified bodies, and manufacturers worldwide [3]. The core of this framework, ISO 10993-1, establishes that biocompatibility must be assessed within a risk management process aligned with ISO 14971, emphasizing hazard identification, risk estimation, and control [3] [5]. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) provides its own guidance on the use of ISO 10993-1, requiring evaluation for devices with direct or indirect body contact and assessing the final finished device in its entirety [4].

The ISO 10993-1 Framework: Evaluation Principles and Endpoints

ISO 10993-1 is the cornerstone standard of the series, providing the overarching principles and requirements for biological evaluation [3]. Its fundamental purpose is to guide manufacturers in identifying, assessing, and managing the biological risks associated with a device's materials, design, and tissue contact during its intended use [3]. The evaluation process is not a simple checklist of tests but a structured risk assessment that begins with a thorough characterization of the device material and its chemical constituents [3] [5].

The standard requires manufacturers to establish a biological evaluation plan, which systematically considers the nature and duration of body contact to determine the necessary biological endpoints for evaluation [1]. The nature of body contact is categorized as surface device, externally communicating device, or implant device, with further sub-divisions based on specific tissues (e.g., intact skin, mucosal membrane, blood, bone) [1]. The contact duration is classified as limited (≤24 hours), prolonged (>24 hours to 30 days), or permanent (>30 days) [1]. This categorization is used to determine which biological endpoints require evaluation. The matrix below summarizes the required and additional endpoints based on device categorization.

Table: ISO 10993-1 Endpoints for Consideration Based on Device Categorization (Adapted from FDA-Modified Matrix) [1]

| Nature of Body Contact | Contact Duration | Cytotoxicity | Sensitization | Irritation | Systemic Toxicity | Genotoxicity | Implantation | Hemocompatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Device (Intact Skin) | A - Limited | X | X | X | ||||

| B - Prolonged | X | X | X | |||||

| C - Permanent | X | X | X | |||||

| Mucosal Membrane | A - Limited | X | X | X | ||||

| B - Prolonged | X | X | X | O | O | O | ||

| C - Permanent | X | X | X | O | O | X | O | |

| Blood Path, Indirect | A - Limited | X | X | X | X | |||

| B - Prolonged | X | X | X | O | O | X | ||

| C - Permanent | X | X | O | O | X | O | X | |

| Implant Device (Tissue/Bone) | A - Limited | X | X | X | O | |||

| B - Prolonged | X | X | X | O | X | X | ||

| C - Permanent | X | X | X | O | X | X | O |

X = ISO 10993-1 recommended endpoints for consideration; O = Additional FDA recommended endpoints for consideration. This is a simplified excerpt; the full matrix includes additional endpoints like chronic toxicity, carcinogenicity, and reproductive toxicity. [1]

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for the biological evaluation of a medical device as prescribed by ISO 10993-1 within a risk management framework.

The "Big Three" and Other Key Biocompatibility Tests

Among the numerous biological endpoints, three tests—cytotoxicity, sensitization, and irritation—are considered the "Big Three" because they are required for almost all medical devices, regardless of their categorization [6]. These tests are often the first line of in vitro screening, with additional tests required based on the device's contact and duration.

Table: Summary of Key Biocompatibility Tests and Their Methodologies

| Test Endpoint | Relevant ISO Standard | Common Test Methods & Protocols | Key Assessment Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytotoxicity | ISO 10993-5 [6] | - Direct contact- Agar diffusion- Extract dilution (elution) using MTT, XTT, or Neutral Red Uptake assays [2] [6]. | Cell viability, morphological changes, cell lysis, and detachment. ≥70% cell viability is often a positive sign [6]. |

| Sensitization | ISO 10993-10 [5] | - Guinea Pig Maximization Test (GPMT)- Local Lymph Node Assay (LLNA)- In vitro methods [6]. | Potential for a material to cause an allergic hypersensitivity response upon repeated exposure. |

| Irritation | ISO 10993-23 [5] | - Skin irritation tests (in vivo or in vitro)- Intracutaneous reactivity test [6]. | Localized inflammatory response not involving an immune mechanism at the contact site. |

| Genotoxicity | ISO 10993-3 [5] | - In vitro assays for gene mutations (e.g., Ames test) and chromosomal aberrations [5]. | Assessment of potential damage to genetic material, which may lead to carcinogenesis. |

| Implantation | ISO 10993-6 [5] | - Device or material is surgically implanted in an animal model (e.g., muscle, bone) for a specified period [5]. | Local effects on living tissue, including inflammation, fibrosis, and encapsulation at the implant site. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: In Vitro Cytotoxicity Testing (ISO 10993-5)

Cytotoxicity testing assesses whether a device's materials or extracts cause damage to living cells [6]. The following is a generalized protocol for the extract dilution method, one of the most common approaches.

1. Sample Preparation (Refer to ISO 10993-12):

- The test device or a representative sample is prepared under clean conditions.

- An extraction is performed using a suitable solvent(s) such as cell culture medium with serum (for polar substances) and vegetable oil or saline (for non-polar substances) [6].

- Extraction conditions (e.g., 37°C for 24-72 hours) are selected based on the device's nature and intended use to simulate clinical exposure.

2. Cell Culture:

- Mammalian cell lines, typically fibroblasts (e.g., L929, Balb 3T3), are cultured in standard conditions [6].

- Cells are seeded into multi-well plates and allowed to attach and grow until they form a near-confluent monolayer.

3. Exposure to Extract:

- The culture medium is replaced with the prepared device extract (neat or diluted).

- Control groups are included: negative control (fresh culture medium, extraction solvent), and positive control (e.g., a solution containing known cytotoxic agents like latex or zinc diethyldithiocarbamate) [6].

- Cells are incubated with the extract for approximately 24 hours at 37°C [6].

4. Assessment of Cytotoxicity:

- Cell Viability Quantification: A reagent like MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide) is added. Metabolically active cells convert MTT to a purple formazan product. The absorbance of the dissolved formazan is measured spectrophotometrically; the intensity correlates with the number of viable cells [6]. Alternative assays include XTT and Neutral Red Uptake.

- Qualitative Morphological Assessment: Cells are examined under a microscope for signs of toxicity, including rounding, detachment from the substrate, cell lysis, and vacuolization [6].

5. Data Interpretation:

- Results are compared to controls. A reduction in cell viability below a certain threshold (e.g., <70% for neat extract) may indicate cytotoxicity [6].

- Any cytotoxic effect requires further investigation and risk assessment within the context of the device's intended use.

Biocompatibility of Organic Electronic Materials

Organic electronic materials represent a frontier in medical device technology, particularly for implantable bioelectronics and biosensors [2] [7]. These materials, which include conducting polymers like PEDOT and semiconducting polymers like DPPT-TT, offer unique advantages for biointegration [2] [7] [8]. Their mechanical properties, such as a low Young's modulus, can be engineered to closely match that of human tissues (e.g., ~10 kPa for the cortex), significantly reducing the mechanical mismatch that often leads to inflammation and fibrous encapsulation around traditional rigid implants [2]. Furthermore, their primary charge carriers can be both electrons and ions, facilitating efficient transduction of signals across the biotic-abiotic interface [2].

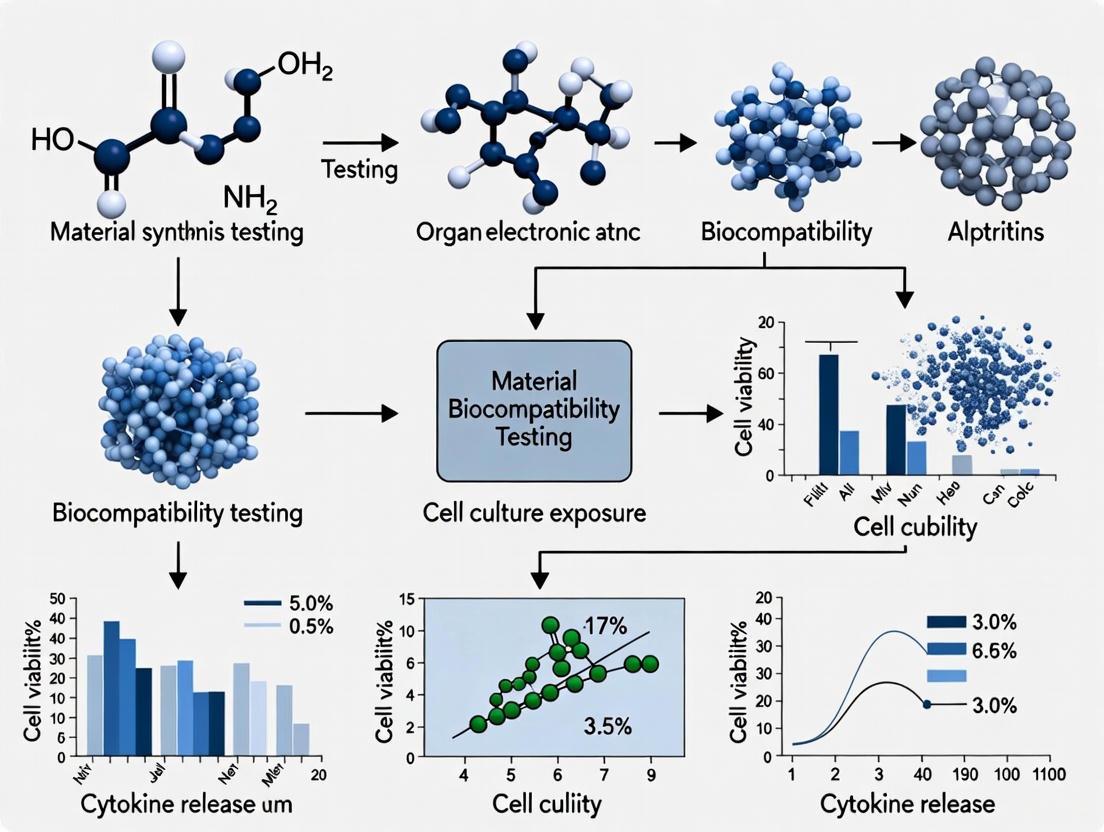

The evaluation of these novel materials follows the same ISO 10993 principles but presents specific challenges and considerations. The following diagram outlines a typical workflow for evaluating a new organic electronic material, from initial screening to in vivo validation.

A recent study exemplifies this process, developing a highly biocompatible and stretchable organic field-effect transistor (sOFET) for implants [7]. The researchers used a blend of a semiconducting polymer (DPPT-TT) and a medical-grade elastomer, bromo isobutyl–isoprene rubber (BIIR), which is known to meet ISO 10993 standards [7]. The material's vulcanization process was carefully controlled to preserve electrical properties while achieving mechanical stability under 50% strain. In vitro assessments with human dermal fibroblasts and macrophages showed no adverse effects on cell viability, proliferation, or migration [7]. Subsequent in vivo implantation studies in mice demonstrated no major inflammatory response or tissue damage, confirming its potential for long-term integration [7]. This highlights the trend of moving beyond "bio-inert" materials to those that can form a more intimate and stable interface with biological tissues.

Table: Comparison of Material Properties: Abiotic, Organic Electronic, and Biotic Tissue

| Aspect | Abiotic Electronic Materials | Organic Electronic Materials | Biotic Living Tissue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Composition | Inorganic metals & semiconductors | Organic molecules & polymers (e.g., PEDOT, DPPT-TT) | Complex mixture of water, proteins, lipids |

| Physical State | Hard solids | Soft solids | Extremely soft solids |

| Young's Modulus | ~100 GPa | 20 kPa - 3 GPa (tunable) | ~10 kPa (cortex) |

| Charge Carriers | Electrons & holes | Electrons, holes, & ions | Ions |

| Primary Biocompatibility Challenge | Mechanical mismatch, chronic inflammation | Long-term stability in physiological environment, biofouling | N/A |

Data synthesized from [2] and [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials for Biocompatibility Research

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biocompatibility Testing

| Reagent / Material | Function in Biocompatibility Evaluation |

|---|---|

| L929 or Balb 3T3 Fibroblast Cell Lines | Standardized mammalian cell lines used for in vitro cytotoxicity testing (ISO 10993-5) [6]. |

| MTT/XTT/Neutral Red Reagents | Tetrazolium-based dyes or uptake assays used to quantitatively measure cell viability and proliferation in cytotoxicity tests [2] [6]. |

| Cell Culture Media with Serum | A polar solvent used for extracting devices to simulate the leaching of hydrophilic chemical constituents [6]. |

| Vegetable Oil or Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Non-polar solvents used for extracting devices to simulate the leaching of lipophilic chemical constituents [6]. |

| Medical-Grade Elastomers (e.g., BIIR) | Biocompatible base materials that serve as an elastic matrix for creating soft, implantable electronic devices, ensuring compliance with ISO 10993 [7]. |

| Conducting Polymers (e.g., PEDOT, PPy) | Organic mixed ionic/electronic conductors that form the active sensing/ stimulating component in bioelectronic devices, enabling efficient interface with biological tissues [2] [8]. |

Defining and demonstrating biocompatibility is a rigorous, context-dependent process governed by the internationally recognized ISO 10993 series. The framework moves beyond simple pass/fail testing, mandating a risk-based evaluation that considers the complete device in its final form. For the burgeoning field of organic bioelectronics, this standard provides the essential pathway to clinical translation. While materials like conducting polymers offer inherent advantages for biointegration due to their soft mechanics and mixed conduction, they must still undergo the same systematic evaluation—from the "Big Three" tests to long-term implantation studies. As research progresses, the synergy between innovative material design and robust standardized evaluation will continue to be the foundation for developing the next generation of safe and effective medical devices.

Why Organic? The Unique Properties of Conjugated Polymers for Biointegration

The emergence of organic bioelectronics represents a paradigm shift in the design of medical and diagnostic devices, effectively bridging the electronic world of semiconductors with the soft, ionic world of biology. Within this field, conjugated polymers have emerged as a premier material class for biointegration, offering a unique combination of electronic functionality and biological compatibility that traditional inorganic materials like silicon and metals lack. These carbon-based semiconductors share a similar chemical "nature" with biological molecules, enabling more seamless integration with living tissues and biological systems [9]. The fundamental challenge in biointegration involves creating interfaces that allow for efficient electronic communication with biological systems without triggering adverse immune responses or mechanical mismatches. Conjugated polymers address this challenge through their tunable chemical, electrical, and mechanical properties, making them ideal candidates for applications ranging from biosensors and neural interfaces to drug delivery systems and tissue engineering scaffolds [9] [10]. This review examines the unique properties that render conjugated polymers exceptional materials for biointegration, with specific comparisons to traditional alternatives and detailed experimental methodologies for evaluating their performance.

Unique Properties of Conjugated Polymers for Biointegration

Mechanical Compatibility with Biological Tissues

The mechanical mismatch between conventional electronic materials and soft biological tissues often leads to fibrotic encapsulation, reduced signal fidelity, and chronic inflammation. Conjugated polymers address this fundamental challenge through their inherent flexibility and tunable mechanical properties.

Table 1: Mechanical Properties of Electronic Materials vs. Biological Tissues

| Material Category | Specific Material | Young's Modulus (GPa) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Fracture Strain (%) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Electronics | Silicon | 160-180 | 7000 | <1 | Brittle, rigid |

| Gold | 78 | 220 | <5 | Dense, stiff | |

| Conjugated Polymers | PEDOT:PSS (dry) | 2-4 | 50-80 | 10-30 | Ductile, flexible |

| PEDOT:PSS (hydrogel) | 0.001-0.1 | 1-10 | 50-200 | Soft, stretchable | |

| Poly(3-hexylthiophene) | 0.5-2 | 30-60 | 5-15 | Thermoplastic | |

| Biological Tissues | Brain Tissue | 0.0005-0.003 | - | 50-100 | Ultra-soft, viscoelastic |

| Skin | 0.015-0.085 | 5-30 | 35-115 | Fibrous, anisotropic | |

| Cardiac Tissue | 0.02-0.5 | 50-150 | 10-15 | Contractile |

Conjugated polymers can be engineered into various forms, including hydrogels with Young's moduli similar to those of soft tissues, significantly reducing mechanical mismatch at the biointerface [9]. This tunability enables the design of devices that minimally impair natural tissue function and reduce foreign body responses. Furthermore, certain conjugated polymers can be processed into three-dimensional architectures because of their solution processability, creating scaffolds that provide structural support while enabling integrated sensing or stimulation within engineered tissues themselves [9].

Mixed Ionic-Electronic Conduction

Biological systems predominantly use ionic conduction for signal transmission, whereas traditional electronics rely solely on electronic conduction. Conjugated polymers uniquely bridge this fundamental divide.

Table 2: Charge Transport Properties in Electronic Materials

| Material Type | Electronic Conductivity (S/cm) | Ionic Conductivity (S/cm) | Charge Carriers | Coupling Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metals | 10⁴-10⁶ | Negligible | Electrons | Poor |

| Inorganic Semiconductors | 10⁻⁶-10³ | Negligible | Electrons/Holes | Poor |

| Traditional Conducting Polymers | 10⁻¹⁰-10³ | 10⁻⁶-10⁻³ | Electrons/Holes | Moderate |

| Organic Mixed Ionic-Electronic Conductors | 10⁻³-10³ | 10⁻⁴-10⁻¹ | Both ions and electrons | Excellent |

Organic mixed ionic-electronic conductors (OMIECs), such as the widely used PEDOT, constitute a special class of materials exhibiting simultaneous electronic and ionic conductivity [10]. This unique combination enables more efficient signal transduction across the biology-electronics interface, as the polymers can directly translate ionic fluxes from biological systems into electronic signals for external devices, and vice versa [9] [10]. Leveraging ion redistribution inside a conjugated polymer upon application of an electrical field and its coupling with electronic charges enables the development of advanced devices such as organic electrochemical transistors (OECTs) that can be engineered to act as artificial neurons or synapses with complex, history-dependent behavior [9].

Chemical Tunability and Functionalization

The molecular structure of conjugated polymers provides unparalleled opportunities for chemical modification to enhance biointegration and introduce specific functionalities. Unlike inorganic semiconductors with fixed crystalline structures, conjugated polymers offer synthetic versatility that enables precise control over their properties through molecular design [9] [11]. Their biological properties can be controlled using a variety of functionalization strategies, including the incorporation of biomimetic peptides, enzyme-sensitive linkages, or anti-fouling molecules to direct specific cellular responses or minimize non-specific protein adsorption [9]. Furthermore, the development of conjugated polyelectrolytes and the ability to incorporate various side chains and functional groups allows researchers to fine-tune solubility, surface energy, and interaction with biological components without compromising electronic functionality [9].

Processability and Form Factor Versatility

Conjugated polymers can be processed using a variety of techniques that enable the creation of devices with form factors conducive to biointegration. These materials are solution-processable, allowing for deposition through low-cost, low-temperature methods such as spin-coating, inkjet printing, and 3D printing, unlike inorganic semiconductors that require high-temperature processing [12] [11]. This enables fabrication on flexible substrates compatible with biological systems. Additive manufacturing techniques allow for the creation of complex three-dimensional structures that can mimic tissue architecture, moving beyond the two-dimensional constraints of traditional electronics [11]. Finally, organic electronic materials can be integrated with a variety of mechanical supports, giving rise to devices with form factors that enable seamless integration with biological systems, including wearable, implantable, and transient electronics [9].

Experimental Characterization and Biocompatibility Assessment

Electrical Performance Characterization

Evaluating the electrical properties of conjugated polymers under biologically relevant conditions is essential for assessing their suitability for biointegration.

Table 3: Standardized Experimental Protocols for Electrical Characterization

| Test Parameter | Experimental Method | Biological Context Protocol | Key Metrics | Relevance to Biointegration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Conductivity | 4-point probe measurement | Measurements in physiological buffer (PBS, 37°C) | Sheet resistance, bulk conductivity | Signal fidelity in wet environments |

| Ionic-Eronic Coupling | Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy | Frequency sweep 0.1-10⁶ Hz in cell culture media | Charge storage capacity, interfacial impedance | Efficiency of biological signal transduction |

| Operational Stability | Continuous cycling in OECT configuration | 10⁴-10⁶ cycles in simulated body fluid | On/off current retention, threshold voltage shift | Device longevity in implantable applications |

| Charge Injection Capacity | Cyclic voltammetry | Scanning at 50 mV/s in relevant potential window | Volumetric capacitance, redox stability | Safety and efficacy of stimulation |

Biocompatibility Testing Workflow

The biological safety evaluation of conjugated polymers follows a structured approach aligned with regulatory frameworks such as ISO 10993, which outlines the required tests for medical devices based on the nature and duration of body contact [13] [14].

The FDA's "Chemical Analysis for Biocompatibility Assessment of Medical Devices" draft guidance emphasizes that chemical characterization forms the foundation of the biological safety assessment [14]. This involves a process of data gathering concerning the materials of construction, their chemical ingredients, and chemical residues originating from the manufacturing process. For conjugated polymers, this includes identifying and quantifying monomers, oligomers, catalysts, dopants, and processing aids that might leach out during device operation. The guidance recommends using multiple analytical techniques (HS-GC/MS, GC/MS, LC/MS, ICP/MS) to profile both organic and elemental extractables, with testing conducted on three separate batches to account for material variability [14].

Experimental Protocol: Cytocompatibility Assessment

Objective: To evaluate the in vitro cellular response to conjugated polymer samples using standardized cytotoxicity and cell adhesion assays.

Materials:

- Sterilized conjugated polymer films (e.g., PEDOT:PSS, PPy, PANI) on appropriate substrates

- Control materials (tissue culture plastic, reference materials)

- Relevant cell line (e.g., NIH/3T3 fibroblasts for general cytotoxicity, PC12 neurons for neural interfaces)

- Complete cell culture medium with serum

- Cell viability assay reagents (MTT, AlamarBlue, or PrestoBlue)

- Immunocytochemistry reagents (fixative, permeabilization buffer, primary/secondary antibodies)

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare sterile test samples in 24-well plate format. Include positive control (e.g., latex extract) and negative control (culture medium only).

- Direct Contact Test: Seed cells directly onto test materials at standard density (e.g., 10,000 cells/well) and culture for 24-72 hours.

- Extract Testing: Prepare extracts by incubating materials in culture medium (3 cm²/mL) for 24-72 hours at 37°C. Apply extracts to pre-seeded cells.

- Viability Assessment: After exposure period, add viability indicator and measure according to manufacturer's protocol.

- Cell Morphology Analysis: Fix cells, stain for actin cytoskeleton and nuclei, and image using fluorescence microscopy.

- Data Analysis: Calculate percentage viability relative to negative control. Assess cell morphology and adhesion quality.

Interpretation: Cell viability >70% relative to negative control is generally considered non-cytotoxic. Additionally, observe cell morphology - well-spread cells with normal morphology indicate good biocompatibility, while rounded cells suggest toxicity or poor adhesion.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Materials for Conjugated Polymer Biointerface Research

| Category | Specific Material/Reagent | Function in Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conjugated Polymers | PEDOT:PSS | Benchmark OMIEC for bioelectronics | Commercial formulations vary; often require optimization |

| Polyaniline (PANI) | pH-responsive conducting polymer | Conductivity dependent on doping state and pH | |

| Polypyrrole (PPy) | Biocompatible polymer for neural interfaces | Typically electropolymerized for device fabrication | |

| Dopants/Additives | Tosylate, PSS | p-type dopants for enhanced conductivity | Impact on biocompatibility must be assessed |

| Ionic liquids | Processing additives and conductivity enhancers | Can improve mechanical properties and stability | |

| Polyethylene glycol (PEG) | Biocompatibility enhancer | Reduces protein fouling, improves wettability | |

| Characterization Tools | Electrochemical workstation | Critical for electrical/electrochemical characterization | Must include impedance capability |

| Quartz crystal microbalance | Monitoring mass changes during swelling/protein adsorption | Combined with electrochemical measurements (EQCM) | |

| Surface plasmon resonance | Label-free monitoring of biomolecular interactions | Provides kinetic binding information | |

| Cell Culture | Primary neurons | Relevant for neural interface development | Requires specialized culture conditions |

| Fibroblasts (e.g., NIH/3T3) | General cytotoxicity screening | Standardized, well-characterized model | |

| Metabolic activity assays | Quantitative cytotoxicity assessment | Multiple platforms available (MTT, AlamarBlue, etc.) |

Conjugated polymers offer a compelling materials platform for biointegration due to their unique combination of mechanical compliance, mixed ionic-electronic conduction, chemical tunability, and versatile processing. These properties enable the development of bioelectronic devices that form more seamless interfaces with biological systems, minimizing foreign body responses while maintaining high electronic performance. As the field progresses, the emphasis is shifting from simply demonstrating biocompatibility to designing multifunctional materials that actively direct desired biological responses. The ongoing development of standardized characterization methodologies and regulatory frameworks will be crucial for translating these promising materials from laboratory research to clinical applications, ultimately enabling new generations of implantable, wearable, and transient bioelectronic devices for healthcare and medical research.

The development of bioelectronic devices for neural interfaces, wearable monitors, and implantable systems demands materials that seamlessly integrate with biological tissues. The fundamental challenge lies in the mechanical and chemical mismatch between conventional electronics and living systems. Traditional rigid electronic materials, such as silicon and metals, possess Young's moduli in the gigapascal range (GPa), while biological tissues like the brain are orders of magnitude softer, with moduli in the kilopascal range (kPa). This mismatch often triggers chronic inflammatory responses, fibrosis, and device failure. Consequently, the field has increasingly turned to soft, organic electronic materials that can bridge this divide. Among these, conductive polymers like PEDOT:PSS and biocompatible elastomers such as Bromo Isobutyl-Isoprene Rubber (BIIR) have emerged as leading candidates. This guide objectively compares the performance, properties, and biocompatibility of these key material classes, providing researchers with the experimental data and methodologies needed for informed material selection.

Material Class Comparison: Properties and Performance

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of major biocompatible material classes for organic electronics, highlighting their respective advantages and limitations.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Biocompatible Electronic Material Classes

| Material Class | Specific Example | Key Electrical Properties | Key Mechanical Properties | Biocompatibility & In Vivo Performance | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conductive Polymers | PEDOT:PSS (PILC Ink) [15] | High conductivity (~286 S/cm) | Storage modulus ~105 Pa; Yield stress ~103 Pa | No post-treatment needed; successful in vivo sciatic nerve stimulation & brain recording [15]. | 3D-printed circuits, on-skin e-tattoos, implantable bioelectrodes [15] [16]. |

| PEDOT:PSS (with additives) [16] | Conductivity up to ~4176 S/cm (when annealed) | Young's modulus tunable from kPa to MPa | High biocompatibility; minimizes foreign-body response [16] [17]. | Neural electrodes for brain monitoring and modulation [16] [18]. | |

| Biocompatible Elastomers | BIIR (Medical Grade) [7] | Semiconductor blend mobility maintained under strain | Young's modulus similar to human tissues (∼107.7 to 108.8 Pa); stable at 50% strain | In vivo studies show no major inflammatory response or tissue damage; meets ISO 10993 [7]. | Skin-like implantable transistors, logic circuits (inverters, NOR/NAND gates) [7]. |

| Hydrogels | PEGDA-GelMA [19] | Primarily ionic conduction | Elastic modulus suitable for soft tissues | Permissive glial layer, induces neovascularization, attracts neuronal progenitors [19]. | Regenerative scaffolds for brain lesions, tissue engineering [19]. |

| Metallic Biomaterials | Ti-6Al-4V (LPBF) [20] | N/A (Conductive substrate) | High strength and corrosion resistance | Good osseointegration; surface roughness and wettability critical for cell adhesion [20] [21]. | Orthopedic implants, load-bearing components, structural supports for bioelectronics [20]. |

Experimental Protocols for Biocompatibility Assessment

Rigorous biocompatibility assessment is paramount for the clinical translation of organic electronic materials. The following protocols detail key methodologies referenced in the literature.

In Vitro Cytotoxicity and Cell Viability Assay

This protocol assesses the short-term toxicological response of cells to material extracts or direct contact, as performed in studies on BIIR elastomers and neural probes [7] [18].

- Principle: To determine if leachable substances from a material affect cell survival, proliferation, and metabolic activity.

- Materials:

- Test Material: Sterilized samples of PEDOT:PSS film, BIIR blend, or other material.

- Cell Line: Relevant cell types such as human dermal fibroblasts, macrophages, or neuronal cell lines.

- Culture Reagents: Cell culture medium, fetal bovine serum, penicillin-streptomycin, phosphate-buffered saline.

- Assay Kits: AlamarBlue, MTT, or Live/Dead viability/cytotoxicity kit.

- Procedure:

- Extract Preparation: Incubate the sterile test material in cell culture medium at 37°C for 24 hours to create an extract. Use culture medium alone as a negative control.

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells in a 96-well plate at a standard density and allow them to adhere for 24 hours.

- Treatment: Replace the medium in the test wells with the material extract. Negative and positive control wells receive fresh medium and a cytotoxic substance, respectively.

- Incubation: Incubate the plate for 24-72 hours.

- Viability Measurement:

- Metabolic Activity: Add AlamarBlue reagent to each well, incubate for 2-4 hours, and measure fluorescence/absorbance.

- Live/Dead Staining: Incubate cells with calcein-AM and ethidium homodimer-1, then visualize under a fluorescence microscope.

- Data Analysis: Cell viability is expressed as a percentage relative to the negative control. A viability of >70-80% is typically considered non-cytotoxic.

In Vivo Implantation and Histological Evaluation

This protocol evaluates the chronic tissue response and functional integration of a material, as used in assessments of PEGDA-GelMA scaffolds and BIIR transistors [19] [7].

- Principle: To monitor the foreign body response, inflammation, and tissue remodeling over time following device implantation.

- Materials:

- Animal Model: Rats or mice, approved by an institutional animal care and use committee.

- Test Device: Sterilized bioelectronic device or material scaffold.

- Surgical Equipment: Stereotaxic apparatus for brain implants or standard surgical tools for subcutaneous implantation.

- Histology Reagents: Paraformaldehyde, sucrose, optimal cutting temperature compound, hematoxylin and eosin stain, antibodies for immunofluorescence.

- Procedure:

- Implantation: Anesthetize the animal and perform a sterile surgical procedure to implant the test material into the target site (e.g., brain, subcutaneous pocket). A sham surgery or inert material implant can serve as a control.

- Monitoring: Allow the animal to recover and monitor behavior and health for a predetermined period (e.g., 4-12 weeks).

- Perfusion and Tissue Harvest: At the endpoint, deeply anesthetize the animal and transcardially perfuse with saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Excise the tissue containing the implant.

- Sectioning and Staining: Cryopreserve the tissue, section it using a microtome, and mount on slides. Perform staining:

- H&E Staining: For general morphology and identifying fibrotic capsules and inflammatory cell infiltration.

- Immunofluorescence: Use antibodies against markers like GFAP (astrocytes), Iba1 (microglia), CD68 (macrophages), and NeuN (neurons) to assess specific cellular responses.

- Data Analysis: Histological sections are scored semi-quantitatively for inflammation, fibrosis, and specific cell presence. A minimal glial scar, low macrophage activation, and presence of neurons near the interface indicate high biocompatibility [19].

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points and methodologies in the biocompatibility assessment pipeline for organic electronic materials.

Biocompatibility Testing Workflow for Organic Electronic Materials

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful research and development in this field rely on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key components and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biocompatible Electronics

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS Colloids | Conductive polymer base for inks; provides mixed ionic-electronic conduction [15] [16]. | Formulation of 3D printable PILC inks for neural probes and e-tattoos [15]. |

| EMIM:TCB Ionic Liquid | Additive to enhance conductivity and induce phase separation in PEDOT:PSS [15]. | Creating highly conductive (286 S/cm), printable PEDOT:PSS colloids without post-treatment [15]. |

| Medical Grade BIIR | Biocompatible elastomer matrix for stretchable semiconductors; provides mechanical compliance [7]. | Fabrication of implantable field-effect transistors with stable performance under strain [7]. |

| DPPT-TT Semiconductor | Donor-acceptor polymer providing charge transport pathways within an elastomer matrix [7]. | Blending with BIIR to create a vulcanized, semiconducting nanofiber network for sOFETs [7]. |

| Phe-Phe Dipeptide | Biocompatible coating to mitigate inflammatory response and tissue rejection at the neural interface [18]. | Coating neural probes via PVD to improve signal-to-noise ratio and biocompatibility in vivo [18]. |

| GelMA (Gelatin Methacrylate) | Photopolymerizable, cell-adhesive hydrogel that promotes tissue integration [19]. | Combining with PEGDA to create biocompatible scaffolds for brain tissue regeneration [19]. |

| Ti-6Al-4V Powder | High-strength, biocompatible metal for structural components and implants [20]. | Laser Powder Bed Fusion (LPBF) 3D printing of patient-specific implant geometries [20]. |

The field of implantable electronics holds transformative potential for continuous health monitoring and therapeutic intervention. A significant challenge, however, lies in the fundamental mechanical mismatch between conventional rigid electronic components and soft, dynamic biological tissues. This mismatch can lead to tissue damage, chronic inflammation, and device failure, ultimately limiting the long-term efficacy of biomedical implants [7]. The extracellular matrix (ECM) of natural tissues is a complex, hydrated milieu that exhibits a wide range of mechanical properties, which are critical for regulating cell behavior, survival, and function [22]. Therefore, achieving tissue-level softness and stretchability is not merely an engineering goal but a biological imperative for seamless biointegration.

This guide objectively compares leading strategies developed to bridge this mechanical gap. By framing the discussion within the broader context of biocompatibility testing for organic electronic materials, we will analyze and compare specific approaches based on their achieved mechanical properties, underlying design principles, and experimental validation. The focus is on providing researchers and scientists with quantitative data and methodologies to inform the selection and development of materials for next-generation bioelectronic devices.

Quantitative Comparison of Mechanical Properties

The mechanical properties of biological tissues provide the critical benchmark for designing compatible electronics. The table below summarizes key mechanical metrics for natural tissues and state-of-the-art soft electronic devices.

Table 1: Mechanical Properties of Biological Tissues and Soft Electronic Devices

| Material / Tissue | Young's Modulus | Stretchability | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural ECM Components [22] | Wide range (kPa to GPa) | Varies by component | Complex, hierarchical protein networks; dynamic and bioactive. |

| Collagen I [22] | Stiff structural protein | Low breaking strain | Gradual stiffening with increasing strain until failure. |

| Elastin [22] | Entropically elastic | High elasticity | Critical for energy storage in tissues like skin and lungs. |

| Conventional Elastomers (e.g., PDMS, SEBS) [23] | MPa range (∼0.5-3 MPa) | High | Orders of magnitude stiffer than most soft tissues. |

| BIIR-based Transistor [7] | ∼107.7 - 108.8 Pa (∼60-800 kPa) | Up to 100% strain | Medical-grade, biocompatible elastomer; stable electrical performance at 50% strain. |

| Soft-Interlayer Design [23] | < 10 kPa (e.g., 5.2 kPa) | > 100% strain | Generalizable design using an intermediate-modulus interlayer to achieve tissue-level softness. |

Analysis of Strategic Approaches

Approach 1: Intrinsically Soft and Biocompatible Elastomeric Composites

This strategy focuses on developing new electronic materials that are intrinsically soft by blending semiconductors with medically approved elastomers.

- Material Design: This approach utilizes a vulcanized blend of a semiconducting polymer (e.g., DPPT-TT) and a medical-grade bromo isobutyl–isoprene rubber (BIIR) elastomer. The surface energy disparity between the components leads to the formation of an interconnected semiconducting nanofiber network within the elastic BIIR matrix [7].

- Key Experimental Findings: Devices maintained stable electrical performance under 50% strain and showed excellent mechanical durability, with consistent mobility after 1,000 stretching cycles at 100% strain. In vitro assessments with human dermal fibroblasts and macrophages showed no adverse effects on cell viability, proliferation, or migration. In vivo implantation in mice showed no major inflammatory response or tissue damage [7].

- Advantages and Limitations:

- Advantages: High biocompatibility certified to ISO 10993 standards; excellent chemical and aging resistance; stable performance under strain.

- Limitations: The Young's modulus, while reduced, remains in the hundreds of kPa range, which is still higher than some ultra-soft tissues.

Approach 2: A Generalizable Soft-Interlayer Design

This approach is a device-level strategy that enables existing stretchable electronic materials with relatively high moduli to be integrated onto ultra-soft substrates.

- Mechanical Principle: A thin interlayer with an intermediate modulus (e.g., SEBS at 2.83 MPa) is inserted between the functional electronic film and an ultra-soft substrate (e.g., hydrogel or soft silicone). This interlayer suppresses stress concentration at defect sites in the electronic film during stretching by providing a more gradual mechanical transition, thereby drastically improving stretchability [23].

- Key Experimental Findings: The addition of a 1.2 μm-thick SEBS interlayer on a polyacrylamide (PAAm) hydrogel substrate resulted in an effective device modulus of 5.2 kPa—over two orders of magnitude lower than devices on conventional elastomers. This design enabled transistor arrays that maintained functionality under over 100% strain [23].

- Advantages and Limitations:

- Advantages: Achieves tissue-level moduli (< 10 kPa); generalizable to various conductors and semiconductors; improves conformability on dynamic, irregular surfaces.

- Limitations: Adds complexity to the device fabrication process; requires strong adhesion between all layers.

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol: In Vitro Biocompatibility Assessment

This protocol is critical for evaluating the biological safety of new electronic materials as per ISO 10993 standards [7].

- Cell Culture: Use relevant cell lines, such as human dermal fibroblasts and macrophages.

- Direct Contact Test: Place sterilized samples of the electronic material (e.g., the BIIR/DPPT-TT blend film) in direct contact with cultured cells.

- Viability Assay: After a standard incubation period (e.g., 24-72 hours), perform a cell viability assay such as AlamarBlue or MTT to quantify metabolic activity.

- Proliferation Assay: Monitor cell proliferation over several days using DNA quantification or direct cell counting.

- Migration Assay: Use a scratch assay or similar method to assess if the material or its leachates affect cell migration.

- Analysis: Compare results against positive (e.g., tissue culture plastic) and negative (e.g., a toxic material) controls. A biocompatible material will show no significant adverse effects on viability, proliferation, or migration compared to the positive control [7].

Protocol: Mechanical and Electrical Performance Under Strain

This protocol evaluates the robustness of soft electronic devices during mechanical deformation [7] [23].

- Device Fabrication: Fabricate the stretchable electronic device (e.g., a transistor or conductor) on a stretchable substrate.

- Mounting on Stretcher: Mount the device on a uniaxial or biaxial mechanical stretcher integrated with electrical measurement probes.

- Baseline Measurement: Record the baseline electrical performance (e.g., conductivity for electrodes, mobility and ON/OFF ratio for transistors).

- Static Strain Test: Apply incremental static strains (e.g., 0%, 10%, 20%, ... up to 100%) and measure the electrical performance at each step.

- Cyclic Strain Test: Subject the device to repeated stretching cycles (e.g., 1,000 cycles at a set strain like 50% or 100%) while monitoring the electrical performance periodically to assess durability.

- Failure Analysis: Use techniques like optical microscopy or scanning electron microscopy (SEM) post-testing to inspect for microcracks or delamination.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials used in the featured research for developing tissue-like soft electronics.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Soft Electronics

| Material / Reagent | Function in Research | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Medical-Grade Elastomers | Biocompatible matrix for intrinsic soft composites; provides shock absorption and low reactivity. | Bromo Isobutyl–Isoprene Rubber (BIIR) [7]. |

| Conjugated Polymers | Provides semiconducting functionality; allows for charge transport in the soft device. | DPPT-TT [7] [23]. |

| Soft Interlayer Material | Enables ultra-soft devices by mitigating stress in functional layers on low-modulus substrates. | Polystyrene-ethylene-butylene-styrene (SEBS H1052) [23]. |

| Ultra-Soft Substrates | Mimics the mechanical environment of soft biological tissues for device integration. | Polyacrylamide (PAAm) Hydrogel, Ecoflex-0010 [23]. |

| Biocompatible Conductors | Create stretchable and corrosion-resistant interconnects and electrodes for implants. | Dual-layer Silver/Gold (Ag/Au) metallization [7]. |

Visualization of the Soft-Interlayer Mechanism

The following diagram illustrates the working mechanism of the soft-interlayer design, which allows high-modulus functional films to achieve excellent stretchability on ultra-soft substrates.

The pursuit of tissue-like softness and stretchability is a cornerstone of modern biocompatible electronics. Researchers have two powerful, validated strategies at their disposal: the development of new intrinsically soft and biocompatible composite materials, and the implementation of a generalizable soft-interlayer design. The choice between an intrinsic material solution versus a device-level engineering approach depends on the specific application requirements, including the target tissue's modulus, the necessary electrical performance, and fabrication constraints. The experimental protocols and data provided herein offer a framework for the objective comparison and further development of these technologies, paving the way for electronics that can seamlessly integrate with the human body for advanced diagnostics and therapies.

The emergence of bioelectronics represents a paradigm shift in medical devices, diagnostic tools, and therapeutic interventions. Unlike conventional electronics that operate exclusively in the realm of electron flow, bioelectronic devices must function within biological environments dominated by ionic charge carriers. This interface creates a fundamental challenge: establishing seamless communication between electronic systems (which conduct electrons and holes) and biological systems (which conduct ions such as Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺, and Cl⁻). Organic electronic materials have emerged as the pivotal solution to this challenge due to their unique ability to conduct both electronic and ionic species, a property known as mixed ionic-electronic conduction [24].

The significance of this field extends across multiple domains, including implanted neural interfaces, wearable health monitoring devices, tissue engineering scaffolds, and sophisticated drug delivery systems [24]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding charge transport mechanisms in biological environments is essential for designing next-generation medical devices and therapeutic platforms. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of charge transport mechanisms, experimental methodologies, and material considerations for developing effective bioelectronic interfaces, with particular emphasis on their biocompatibility testing context.

Fundamental Charge Transport Mechanisms: A Comparative Analysis

Electronic Versus Ionic Conduction

In biological environments, charge transport occurs through distinct yet sometimes interconnected mechanisms. Electronic conduction involves the movement of electrons and holes through extended states or hopping between localized states, while ionic conduction involves the movement of charged atoms or molecules through fluids, tissues, and materials [25]. Mixed ionic-electronic conductors (OMIECs) represent a special class of materials that can support both transport mechanisms simultaneously, making them particularly valuable for biointerfacing applications [26].

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of Charge Carriers in Biological Environments

| Property | Electronic Conduction | Ionic Conduction | Mixed Conduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charge Carrier | Electrons/Holes | Ions (Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺, Cl⁻) | Both electrons and ions |

| Transport Mechanism | Band transport or hopping | Drift/diffusion in electrolytes | Coupled ionic-electronic transport |

| Speed | Fast (approaching speed of light) | Slow (limited by ion mobility) | Intermediate |

| Typical Mobility | 10⁻⁵ - 10 cm²/V·s [27] | 10⁻⁷ - 10⁻³ cm²/V·s [25] | Varies with composition |

| Temperature Dependence | Decreases with temperature | Increases with temperature | Complex dependence |

| Dominant in | Conventional electronics | Biological systems | Bioelectronic interfaces |

Material Classes for Bioelectronic Interfaces

Different material classes exhibit distinct charge transport properties that determine their suitability for biological applications. Understanding these differences is crucial for selecting appropriate materials for specific bioelectronic devices.

Table 2: Charge Transport Properties of Materials for Biological Environments

| Material Class | Example Materials | Charge Transport Mechanism | Key Characteristics | Biocompatibility Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Mixed Ionic-Electronic Conductors | PEDOT:PSS, PANI [24] | Mixed ionic-electronic conduction | High flexibility, biocompatibility, volumetric capacitance >30 F/cm³ [26] | Excellent biocompatibility; require leaching tests for residual monomers [28] |

| Inorganic Semiconductors | Silicon, Germanium [29] | Primarily electronic conduction | Rigid, band-like transport, high mobility (0.1-10 cm²/V·s) [27] | Often require surface modification for biocompatibility [21] |

| Bio-sourced Materials | Conductive protein fibers, eumelanin [30] [25] | Mixed protonic-electronic conduction | Sustainable, often contain mobile ions and protons | Naturally biocompatible; may require cross-linking |

| Metallic Biomaterials | Titanium alloys, Stainless Steel 316L [21] | Electronic conduction | High strength, excellent conductivity | Good corrosion resistance; potential metal ion release |

| Conductive Hydrogels | PEG-based hydrogels, conductive polymer composites | Primarily ionic with electronic pathways | High water content, tissue-like mechanical properties | Excellent biocompatibility; tunable degradation |

Experimental Characterization Methodologies

Electrical Transport Measurements

Characterizing charge transport in biological environments requires specialized methodologies that account for the unique properties of biological systems. DC electrical measurements provide foundational information about steady-state conductivity but cannot distinguish between different charge carrier types without complementary techniques [30]. For protein-based conductive materials like M13 bacteriophage and engineered aromatic curli fibers, time-domain analysis of DC measurements can reveal transient ionic transport phenomena alongside steady-state electronic conductivity [30].

Impedance spectroscopy extends these capabilities by measuring material response across a frequency spectrum, enabling researchers to deconvolute ionic and electronic contributions to overall conductivity. This technique is particularly valuable for characterizing OMIECs, where the volumetric capacitance (cᵥ) and electronic mobility (μₑ) jointly determine device performance [26]. The characteristic impedance (z₀) of OMIEC channels can be modeled using RC series circuits with the relationship z₀ = 1/(jωcᵥWtₕ) + (ρᵢₒₙtₕ)/W, where W is width, tₕ is thickness, and ρᵢₒₙ is ionic resistivity [26].

Biocompatibility Assessment Protocols

For materials intended for biological environments, comprehensive biocompatibility testing is essential according to ISO 10993 standards [21]. These assessments evaluate multiple aspects of material-biological system interactions:

- Cytotoxicity testing assesses material effects on cell viability and proliferation

- Sensitization assays evaluate potential allergic responses

- Irritation tests examine local inflammatory responses

- Systemic toxicity evaluation assesses material effects on entire organisms

- Implantation studies evaluate material performance in realistic biological environments over extended periods [21]

Materials characterization forms the foundation of biocompatibility assessment, beginning with chemical characterization through infrared analysis, aqueous physicochemical tests, and chromatographic methods to identify potential leachables [28]. These tests determine nonvolatile residue, residue on ignition, buffering capacity, and heavy metal content, establishing baseline material properties before biological testing [28].

Signaling Pathways and Transport Models

Signal Propagation in Mixed Conductors

In organic mixed ionic-electronic conductors (OMIECs), signal propagation involves complex interactions between electronic and ionic charge carriers. When a voltage is applied to an OMIEC channel immersed in an electrolyte, the moving potential front alters local charge distribution through ejection of mobile cations, which electrostatically couple with fixed acceptors in the material's ionic phase [26]. This process results in capacitive ionic currents flowing from the OMIEC layer into the surrounding electrolyte, dissipating a portion of the electronic current traveling along the channel.

The propagation of electrical signals through mixed-conducting channels can be modeled using a transmission line model derived from the drift-diffusion equations [26]. This model describes how voltage signals travel through OMIEC thin films with specific length (L), width (W), and thickness (tₕ) parameters. The propagation constant (γ) is defined as γ = √(r₀/z₀) = √[(jωcᵥρₑₗ)/(1+jωcᵥρᵢₒₙtₕ²)], where r₀ is electronic resistance per unit length, z₀ is characteristic impedance, ω is frequency, cᵥ is volumetric capacitance, and ρₑₗ and ρᵢₒₙ are electronic and ionic resistivities, respectively [26].

Biological Signal Transduction Pathways

In biological systems, signal transduction involves conversion between ionic and electrical signals. Voltage-gated ion channels in excitable cells (neurons, muscle cells) open in response to membrane potential changes, allowing specific ions to flow down their electrochemical gradients [24]. This ionic flux alters the local membrane potential, propagating signals along cell membranes. Bioelectronic interfaces interact with these native signaling pathways through multiple mechanisms:

- Capacitive coupling involves displacement currents from ionic charge redistribution

- Faradaic coupling involves electron transfer across the electrode-electrolyte interface

- Electrostatic modulation uses applied electric fields to influence channel gating

- Electrothermal effects leverage localized heating to alter membrane properties

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful research into charge transport in biological environments requires specialized materials and characterization tools. The following table outlines essential components of the experimental toolkit for researchers in this field.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Charge Transport Studies in Biological Environments

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conductive Polymers | PEDOT:PSS, PANI [24] | Mixed ionic-electronic conduction for biointerfaces | Require purification to remove cytotoxic synthetic byproducts |

| Bio-sourced Materials | M13 bacteriophage, engineered curli fibers [30] | Sustainable bioelectronic materials | Exhibit both transient ionic and steady-state electronic transport |

| Characterization Electrodes | Interdigitated micro-electrodes, Ag/AgCl reference electrodes [30] | DC and AC electrical characterization | Electrode geometry affects current distribution and field lines |

| Electrolytes | Phosphate buffered saline (PBS), artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) | Simulating biological environments | Ionic composition affects charge transport mechanisms |

| Biocompatibility Assessment Tools | Cell culture models, extraction fluids [21] [28] | Evaluating biological safety | Include both aqueous and alcohol extracts for comprehensive profiling |

| Structural Characterization | FTIR, HPLC, GC-MS [28] | Material composition and purity analysis | Identify potentially cytotoxic leachables and degradation products |

Performance Comparison and Optimization Strategies

Key Performance Metrics Across Material Systems

Evaluating bioelectronic materials requires multidimensional assessment across electronic, ionic, mechanical, and biological compatibility parameters. The following comparative analysis highlights trade-offs and optimization opportunities across material classes.

Table 4: Comprehensive Performance Comparison of Bioelectronic Materials

| Performance Metric | Organic Mixed Conductors | Inorganic Semiconductors | Bio-sourced Materials | Metallic Biomaterials |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Mobility (cm²/V·s) | 10⁻⁵ - 10⁻¹ [27] | 0.1 - 10 [27] | <10⁻³ [25] | >1 |

| Ionic Conductivity (S/cm) | 10⁻³ - 10⁻¹ | <10⁻⁶ | 10⁻⁵ - 10⁻² [25] | Not applicable |

| Young's Modulus (GPa) | 0.001 - 1 [24] | 50 - 200 | 0.1 - 10 | 100 - 200 |

| Biocompatibility | Excellent [24] | Good with surface modification | Excellent [25] | Good (varies by alloy) |

| Stability in Physiological Environments | Months to years | Years | Days to months | Years to decades |

| Signal Propagation Speed | Intermediate [26] | Fast | Slow | Fast |

| Tunability | High through side-chain engineering | Limited | Moderate through genetic engineering | Limited |

Optimization Strategies for Enhanced Performance

Based on current research, several strategies have emerged for optimizing charge transport in biological environments:

- Molecular engineering of conjugated polymers with ethylene glycol side chains enhances ion uptake and volumetric capacitance, critical figures of merit for OMIEC performance [26]

- Nanostructuring of conductive materials increases surface area-to-volume ratios, improving interfacial contact with biological tissues

- Composite material systems combine advantageous properties of individual components, such as conductive polymers with hydrogels for enhanced ionic transport

- Surface functionalization with biological recognition elements (peptides, enzymes) facilitates specific interactions with target tissues

- Device geometry optimization balances signal propagation speed with energy dissipation, guided by transmission line models [26]

For researchers developing new bioelectronic materials, the most successful approaches often involve iterative design cycles that combine computational modeling of charge transport with empirical biocompatibility assessment. This integrated methodology ensures that materials meet both electronic performance requirements and biological safety standards essential for clinical translation.

Methodologies and Applications: From ISO Standards to Advanced Testing Platforms

The ISO 10993 series, developed by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) Technical Committee 194, provides a globally harmonized framework for evaluating the biological safety of medical devices [6]. As medical devices increasingly incorporate advanced materials like organic electronic components, this standard offers the foundational principles for assessing their biocompatibility within a structured risk management process [3]. The evaluation process mandated by ISO 10993-1 requires manufacturers to identify, assess, and manage biological risks associated with device materials, design choices, and tissue contact during intended use [3]. For researchers developing implantable organic electronics, this standard provides the critical pathway for demonstrating device safety and achieving regulatory compliance across international markets [7] [31].

The significance of this framework has grown with the recent publication of ISO 10993-1:2025, which represents a substantial evolution from the 2018 version [32] [33]. This latest revision further aligns the biological evaluation process with the risk management principles of ISO 14971, emphasizing a more science-based approach that can reduce unnecessary animal testing while ensuring patient safety [3] [6]. For the field of organic bioelectronics, where materials must seamlessly interface with biological tissues, understanding this framework is not merely a regulatory requirement but a fundamental component of responsible device development [7] [34].

Core Principles and Key Updates in ISO 10993-1:2025

Risk Management Integration

The 2025 revision of ISO 10993-1 establishes a tighter connection with ISO 14971, making biological evaluation a dedicated component within the overall risk management process [32]. The standard now explicitly requires the identification of biological hazards, definition of biologically hazardous situations, and establishment of potential biological harms [32]. This alignment extends to requiring biological risk estimation based on the severity and probability of harm, mirroring the methodology described in ISO 14971 [32]. The updated framework introduces a structured biological evaluation process that follows ISO 14971's lifecycle approach, ensuring biological safety is assessed continuously from design through post-market surveillance [32].

Practical Application Considerations

The revised standard introduces several important practical changes that affect how biological evaluations are planned and executed. Reasonably foreseeable misuse must now be considered during device categorization, including scenarios such as "use for longer than the period intended by the manufacturer" [32]. The determination of exposure duration has been refined with new definitions for "total exposure period," "contact day," "daily contact," and "intermittent contact," replacing the previous approach of simply summing contact seconds [32]. Additionally, the standard introduces new considerations for bioaccumulation, stating that if a chemical known to bioaccumulate is present in the device, the contact duration should be considered long-term unless otherwise justified [32].

Table 1: Key Changes in ISO 10993-1:2025 Revision

| Aspect | ISO 10993-1:2018 | ISO 10993-1:2025 | Impact on Organic Electronics Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Management Integration | General alignment with ISO 14971 | Tightly integrated framework with specific biological risk estimation requirements | Requires more rigorous documentation of risk-benefit analysis for novel materials |

| Device Categorization | Based on nature of body contact & duration | Simplified contact groups; eliminated externally communicating devices category | Streamlined classification for implantable organic electronics |

| Foreseeable Misuse | Focused primarily on intended use | Must consider systematic misuse scenarios | Broader safety assessment for wearable/organic electronic devices |

| Exposure Duration Determination | Used "transitory" for very brief contact | "Very brief contact" remains; any contact >1 minute defaults to one-day exposure | Important for transient organic electronic devices that may have short but repeated contact |

| Systemic Toxicity Evaluation | Based on contact duration and nature | Should reflect duration of use | Critical for biodegradable organic electronic implants |

| Genotoxicity Assessment | Required for certain contact categories | Now applies to all devices with prolonged contact (unless intact skin only) | Expanded testing likely needed for most implantable organic electronic materials |

The "Big Three" Biocompatibility Tests: Foundation of Safety Assessment

Cytotoxicity Testing

Cytotoxicity testing evaluates whether a medical device's materials or components can cause damage to living cells, serving as the first line of screening in biological safety assessment [6]. According to ISO 10993-5:2009, this testing typically involves exposing cultured mammalian cells (such as Balb 3T3, L929, or Vero cell lines) to extracts of the medical device for approximately 24 hours [6]. The methodology involves preparing device extracts using appropriate solvents (physiological saline, vegetable oil, or cell culture medium) under standardized conditions, then exposing the cells to these extracts [6]. Key assessment endpoints include cell viability (measured via MTT, XTT, or neutral red uptake assays), morphological changes, cell detachment, and cell lysis [6]. While ISO 10993-5 doesn't define strict acceptance criteria, cell survival of 70% or higher is generally considered a positive indicator, particularly when testing neat extract [6].

Irritation and Sensitization Testing

Irritation testing assesses the localized inflammatory response that can occur at the contact site between a device and body tissues, while sensitization testing evaluates the potential for materials to cause allergic reactions [6]. These tests are particularly relevant for organic electronic devices that may incorporate novel polymers, elastomers, or conductive materials that have not been previously used in medical applications. The experimental protocols for these assessments may utilize in vitro methods, though the medical device industry has been slower to adopt alternatives to animal testing compared to other sectors [6]. For organic electronic materials, which often contain complex aromatic compounds or metal nanoparticles, thorough irritation and sensitization assessment is crucial for identifying potential biological reactions before clinical use.

Table 2: The "Big Three" Biocompatibility Tests for Medical Devices

| Test Type | Purpose | Standard Methods | Key Endpoints | Relevance to Organic Electronics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytotoxicity | Assess cell damage potential | ISO 10993-5:2009; In vitro cell culture | Cell viability, Morphological changes, Cell detachment | Critical for ensuring novel semiconductors and elastomers aren't toxic to surrounding tissues |

| Irritation | Evaluate localized inflammatory response | In vitro and in vivo models | Tissue inflammation, Erythema, Edema | Important for wearable organic electronics and implantable devices with sustained tissue contact |

| Sensitization | Assess allergic reaction potential | Guinea pig maximization, Local lymph node assay | Allergic response, Immune activation | Essential for devices containing potential allergens like certain metals or organic compounds |

Application to Organic Electronic Materials Research

Biocompatibility Challenges in Organic Bioelectronics

Organic electronic materials present unique biocompatibility challenges that require careful consideration within the ISO 10993 framework. While these materials offer advantageous properties like flexibility, softness, and compatibility with biological tissues, their complex chemical structures and potential degradation products necessitate thorough safety assessment [34]. Traditional inorganic semiconductors face issues of mechanical mismatch with biological tissues, potentially leading to tissue damage, inflammation, fibrosis, and necrosis over time [7]. Although organic semiconductors better match the mechanical properties of tissues, many industrial-grade elastomers used in stretchable organic field-effect transistors (sOFETs) are not certified for biocompatibility and may induce chronic foreign body reactions [7].

Recent research has demonstrated promising approaches to these challenges. The development of elastomeric organic transistors using medical-grade bromo isobutyl–isoprene rubber (BIIR) blended with semiconducting polymers shows how material selection can enhance both performance and biocompatibility [7]. These devices have exhibited stable electrical performance under mechanical strain (up to 50% elongation) while demonstrating compatibility with human dermal fibroblasts and macrophages in vitro, and showing no major inflammatory response or tissue damage in mouse implantation studies [7]. Such advances highlight how the ISO 10993 framework guides the development of safer organic electronic implants through systematic biological evaluation.

Material Selection and Characterization Strategies

Successful biological evaluation of organic electronic devices begins with strategic material selection. Medical-grade elastomers like BIIR, which meet stringent biocompatibility standards set by ISO 10993 and European Pharmacopoeia, provide advantageous starting points for device development [7]. These materials offer excellent mechanical properties including shock absorption, low permeability, aging resistance, and high physical strength, alongside high chemical resistance and low reactivity with microorganisms [7]. The material characterization process for organic electronic devices should include thorough analysis of potential leachables and degradation products, particularly for devices intended for long-term implantation where bioaccumulation potential must be assessed [32].

Experimental Protocols for Biocompatibility Assessment

Cytotoxicity Testing Protocol (Based on ISO 10993-5)

The standardized methodology for cytotoxicity testing provides a reproducible approach for evaluating organic electronic materials. The extraction process involves immersing the test material in extraction solvents (such as physiological saline and vegetable oil) at a surface area-to-volume ratio of 3-6 cm²/mL, then incubating at 37°C for 24 hours [6]. The cell culture preparation requires seeding appropriate mammalian cell lines (L929 fibroblasts are commonly used) in 96-well plates and incubating until approximately 80% confluent [6]. For the extract exposure, culture medium is replaced with device extracts (neat and diluted) and incubated for 24±2 hours at 37°C in a 5% CO₂ atmosphere [6]. The viability assessment typically uses the MTT assay, where yellow MTT tetrazolium salt is reduced to purple formazan in metabolically active cells; absorbance is measured at 570 nm, with cell viability calculated as a percentage of negative control values [6].

In Vivo Implantation Study Protocol

For implantable organic electronic devices, in vivo assessment provides critical safety data not obtainable through in vitro methods. The sample preparation involves sterilizing test and control materials using validated methods that don't alter material properties [7]. The surgical implantation typically uses rodent models, with materials implanted subcutaneously or in muscle pockets according to standardized surgical protocols [7]. The study duration depends on the intended use of the device, with explanation timepoints at 1, 4, 12, and 26 weeks to assess tissue response over time [7]. The histopathological evaluation involves embedding explanted tissues in paraffin, sectioning, and staining with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for evaluation of inflammatory cell response, fibrosis, necrosis, and tissue integration [7]. A scoring system is used to semi-quantitatively assess the biological response, comparing test articles to negative and positive controls [7].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Biocompatibility Testing of Organic Electronics

| Reagent/Cell Line | Function in Biocompatibility Assessment | Application Example | Standard Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| L929 Fibroblast Cell Line | In vitro cytotoxicity testing | Assessment of cell viability after exposure to device extracts | ISO 10993-5 [6] |

| Physiological Saline | Polar extraction solvent | Extraction of hydrophilic compounds from organic electronic devices | ISO 10993-12 [6] |

| Vegetable Oil | Non-polar extraction solvent | Extraction of lipophilic compounds from organic electronic devices | ISO 10993-12 [6] |

| MTT Tetrazolium Salt | Cell viability indicator | Quantitative measurement of metabolic activity in cytotoxicity testing | ISO 10993-5 [6] |

| Medical-Grade Elastomers (BIIR) | Biocompatible substrate material | Creating stretchable semiconductor films for implantable transistors [7] | ISO 10993-1 [7] |

| Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) | Cell culture medium | Maintaining cell cultures during extract exposure studies | ISO 10993-5 [6] |

The ISO 10993 series provides an essential framework for navigating the complex biological evaluation requirements for medical devices, with particular relevance for the emerging field of organic bioelectronics. The recently published ISO 10993-1:2025 standard reinforces the risk-based approach to biological safety assessment, offering a more structured pathway for evaluating novel materials and devices [32] [33]. For researchers developing organic electronic implants, understanding this framework is not merely a regulatory hurdle but a fundamental component of responsible device development that ensures patient safety while facilitating global market access [3] [31].

Successful implementation requires early integration of biological safety considerations into the material selection and device design process, thorough chemical characterization to identify potential biological risks, and strategic testing that addresses both standard requirements and device-specific considerations [32] [6]. As the field advances, the continued development of alternative testing methods that reduce animal use while maintaining scientific rigor will be essential for addressing the unique challenges posed by organic electronic materials [6]. By embracing the structured approach provided by the ISO 10993 series, researchers can more efficiently translate innovative organic electronic technologies from laboratory concepts to clinically viable medical devices.

The development of safe and effective organic electronic medical devices, from implantable neural interfaces to smart wound dressings, hinges on rigorous biocompatibility testing [35] [36]. For researchers and drug development professionals, demonstrating that these novel materials do not provoke adverse biological reactions is a critical step in the translation from laboratory to clinical application. The international standard ISO 10993 series provides the foundational framework for this evaluation, mandating a risk-based assessment strategy [37] [38]. Within this framework, three core in vitro tests—cytotoxicity, sensitization, and irritation—form an essential triad of preliminary safety assessments required for almost all medical devices [6] [39]. This guide objectively compares the methodologies, experimental data, and protocols for these "Big Three" assays, providing a vital reference for the safety evaluation of innovative organic electronic materials.

The "Big Three" tests are considered fundamental because they screen for the most immediate and critical biological risks: cell death, allergic response, and localized inflammation [6]. Cytotoxicity assesses whether a material or its extracts are toxic to living cells, potentially causing cell death or inhibiting cell growth [39]. Sensitization evaluates the potential of a material to cause an allergic reaction, specifically a delayed (Type IV) hypersensitivity response, upon repeated exposure [37] [39]. Irritation testing determines if a material causes localized, reversible inflammatory effects on skin or other tissues, without involving the immune system in an allergic capacity [39]. The transition towards New Approach Methodologies (NAMs), including validated in vitro and in silico methods, is a key trend driven by ethical imperatives, scientific innovation, and regulatory support, such as the U.S. FDA Modernization Act 2.0 [37].

Table 1: Core Comparison of the "Big Three" Biocompatibility Tests

| Test Endpoint | Primary Objective | Governing ISO Standard | Commonly Used In Vitro Methods | Key Measured Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytotoxicity | To determine if a material causes toxicity to cells, leading to cell death or inhibited growth [39]. | ISO 10993-5 [6] [39] | MEM Elution Test, MTT/XTT Assay, Direct Contact, Agar Diffusion [38] [40] | Cell viability (%), morphological changes, cell lysis, detachment [6] [39] |