Advanced Strategies for Water Permeation Prevention in Bioelectronic Encapsulation

This article provides a comprehensive overview of cutting-edge encapsulation technologies designed to prevent water and ion permeation in implantable and wearable bioelectronics.

Advanced Strategies for Water Permeation Prevention in Bioelectronic Encapsulation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of cutting-edge encapsulation technologies designed to prevent water and ion permeation in implantable and wearable bioelectronics. It explores the foundational challenges posed by the body's diverse pH environments and mobile tissues, details innovative material solutions like liquid-based encapsulation, and offers methodological guidance for implementation. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content further covers critical troubleshooting for long-term reliability and outlines rigorous validation frameworks, including in vitro and in vivo benchmarking, to ensure device stability and clinical translation.

The Critical Challenge: Why Water and Ion Permeability Threaten Bioelectronic Longevity

Troubleshooting Guides

Encapsulation Failure in Acidic or Alkaline Environments

Problem: Bioelectronic device failure shortly after implantation in non-neutral pH environments (e.g., stomach, chronic wounds).

- Possible Cause 1: Conventional encapsulation materials like silicone elastomer or Parylene C degrade rapidly in extreme pH.

- Solution: Transition to a liquid-based encapsulation approach using oil-infused elastomers. This provides a superior barrier against H⁺ and OH⁻ ion penetration [1].

- Possible Cause 2: The encapsulation material lacks the necessary mechanical compliance, leading to microcracks in harsh environments.

Loss of Optical Transparency in Optoelectronic Implants

Problem: Encapsulated optoelectronic devices (e.g., LEDs) show dimmed light output or failure.

- Possible Cause: The encapsulation layer has low optical transmittance, scattering or absorbing light.

- Solution: Use materials with high inherent transparency. Oil-infused elastomers have an average optical transmittance of 86.67% across visible wavelengths (380–700 nm), making them suitable for optoelectronics [1].

Mechanical Failure Due to Organ Mobility

Problem: Device encapsulation cracks or delaminates when implanted in mobile organs like the gastrointestinal tract.

- Possible Cause: A mechanical mismatch between stiff encapsulation and soft, dynamic tissues.

- Solution: Select materials with a failure strain close to 100% and a Young's modulus on the order of MPa, which matches the mechanical properties of various biological systems [1].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Encapsulation Materials in Hostile Environments

| Material | Avg. Optical Transmittance (%) | Failure Strain (%) | Young's Modulus | Performance in Acidic pH (e.g., pH 1.5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oil-Infused Elastomer | 86.67 | ~100 | ~MPa | Outstanding; functional for nearly 2 years in vitro [1] |

| Silicone Elastomer | 95.33 | ~100 | ~MPa | Fails rapidly [1] |

| Parylene C | 87.43 | <5 | ~GPa | Loses >20% performance within 1.5-19 days [1] |

| Polyimide (PI) | 7.70-71.22 | <5 | ~GPa | Not specified for long-term acidic exposure [1] |

| Liquid Metal | 0.01 | Not specified | Not specified | Susceptible to corrosion under low pH [1] |

Table 2: Quantitative Barrier Performance of Liquid-Based Encapsulation

| Test Environment | Device Type | Encapsulation Method | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extremely Acidic (pH = 1.5, 4.5) | NFC Antenna | Oil-Infused Elastomer | Maintained functionality for ~2 years in vitro [1] |

| Alkaline (pH = 9.0) | Wireless Optoelectronics | Oil-Infused Elastomer | Demonstrated robust encapsulation [1] |

| Physiological (pH = 7.4) | Wireless Optoelectronics | Oil-Infused Elastomer | Year-long performance in vitro; 3 months in vivo in mice [1] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What makes extreme pH environments so challenging for bioelectronic encapsulation? Biological environments like the gastrointestinal system (pH as low as 1.5) and chronic wounds (pH up to 8.9) contain high concentrations of H⁺ or OH⁻ ions. These ions can penetrate encapsulation materials, leading to current leakage, corrosion of metal components, and eventual device failure. Many flexible materials are only designed for neutral physiological pH (7.4) and fail quickly in these demanding conditions [1].

Q2: How does the liquid-based encapsulation platform work? This bioinspired approach involves creating a roughened polymer elastomer (e.g., PDMS) and infusing it with a hydrophobic oil, such as Krytox (a perfluoropolyether fluid) [1] [2]. The oil fills the micro-scale defects and pores in the polymer matrix, eliminating low-energy pathways for water and ion diffusion. Furthermore, the oil causes water molecules to diffuse as clusters, which dramatically reduces the water permeation rate [2] [3].

Q3: Can this encapsulation method be used for devices requiring wireless communication and power transfer? Yes. Near-Field Communication (NFC) antennas, which are critical for wireless power and data transmission in implants, have been successfully encapsulated with this method. These devices maintained functionality after long-term soaking in acidic environments, proving the compatibility of liquid-based encapsulation with wireless technologies [1] [4].

Q4: Is the oil-infused elastomer biocompatible for long-term implantation? Research demonstrates promising biocompatibility. Immunohistochemistry studies in mice showed that the oil-coated elastomer material is biocompatible. Furthermore, encapsulated wireless optoelectronic devices maintained robust operation and were well-tolerated throughout 3-month implantations in freely moving mice [1].

Q5: The encapsulation seems effective on the top and bottom surfaces. What about the cut edges? The side edges are a potential failure point as they lack the roughened structure to lock in the oil. This can be mitigated by optimizing the laser-cutting parameters during device fabrication. Using a lower cutting speed and specific frequency (e.g., 30 kHz at 100 mm/s) creates a rougher edge surface, which helps retain the protective oil layer and enhances long-term barrier performance [1].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of Oil-Infused Elastomer Encapsulation

This methodology details the preparation of a flexible, transparent, and pH-resistant encapsulation for implantable bioelectronics [1].

Key Reagent Solutions:

- PDMS Elastomer: A silicone-based polymer used as the base substrate.

- Krytox Oil: A synthetic perfluoropolyether (PFPE) fluid with an ultralow water diffusion coefficient, serving as the infused barrier liquid [1].

- Abrasive Paper: Used as a template to create a roughened surface on the PDMS.

Workflow:

- Elastomer Roughening: Create a ~100 µm thick roughened PDMS elastomer film using a molding technique with abrasive paper as a template. The resulting surface should have an arithmetical mean height (Sa) of ~4.7 µm [1].

- Device Sandwiching: Place the implantable bioelectronic device between two layers of the rough elastomer film, with the rough surfaces facing outward.

- Curing: Cure the PDMS-sandwiched device at ambient temperature overnight.

- Laser Cutting: Cut the encapsulated device to the desired shape using a UV laser. Optimize parameters (e.g., 30 kHz frequency, 100 mm/s speed) to create rougher edges for better oil retention [1].

- Oil Infusion: Infuse Krytox oil (to a thickness of ~15 µm) into the rough structures of the elastomer surfaces using a vacuum desiccator.

Protocol 2: In-Vitro Testing in Broad pH Environments

This protocol describes a method to validate the encapsulation's performance across a range of biologically relevant pH conditions [1].

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Buffer Solutions: Prepare solutions at pH 1.5, 4.5, 7.4, and 9.0 to simulate highly acidic, mildly acidic, physiological, and alkaline biological environments.

- NFC Antennas/Wireless Optoelectronics: These are used as model implantable devices for testing.

Workflow:

- Device Preparation: Encapsulate NFC antennas or wireless optoelectronic devices using the oil-infused elastomer method.

- Immersion Test: Soak the encapsulated devices in the different pH buffer solutions. Ensure devices are fully immersed.

- Performance Monitoring: Regularly measure and record device performance metrics. For NFC antennas, this involves monitoring wireless power transfer efficiency and data integrity. For optoelectronics, assess light output stability and device operation.

- Duration: Conduct tests over extended periods (e.g., days to months) to assess long-term durability. Compare the performance with devices encapsulated using conventional materials like plain silicone or Parylene C.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Liquid-Based Encapsulation Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| Krytox Oil | A perfluoropolyether (PFPE) fluid infused into the elastomer to create the primary water/ion barrier [1]. | Ultralow water diffusion coefficient; hydrophobic [1]. |

| PDMS (Polydimethylsiloxane) | A silicone elastomer used as the flexible substrate and structural matrix for the encapsulation [1]. | High optical transparency; stretchable (up to ~100% strain); biocompatible. |

| Abrasive Paper | A template used during the molding process to create a microscopically rough surface on the PDMS film. | The roughness (Sa ~4.7 µm) is critical for mechanically locking the infused oil in place [1]. |

| NFC Antenna | A model implantable device component used for testing encapsulation performance for wireless applications [1] [4]. | Enables wireless power transfer and data communication; sensitive to corrosion. |

| Wireless Optoelectronic Device | A model implantable device (e.g., with LED) used to test encapsulation's optical and functional integrity [1]. | Requires encapsulation with high optical transparency and mechanical flexibility. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary failure modes for bioelectronic encapsulation? The primary failure modes are current leakage, corrosion, and device degradation. These are predominantly initiated by the ingress of water and ions from body fluids, which can lead to electrical shorts, metal corrosion, delamination of encapsulation layers, and a cascade of effects that ultimately result in device malfunction or complete failure [5] [6].

2. Why is encapsulation particularly challenging for implantable bioelectronics? Biological environments are highly dynamic, presenting challenges from broad pH ranges (from pH 1.5 in the stomach to pH 8.9 in chronic wounds), constant mechanical motion, and the presence of corrosive ions. Encapsulation must provide a superior barrier against these factors while remaining mechanically compliant to match the softness of surrounding tissues [1] [7].

3. How can I test the long-term reliability of a new encapsulation material in vitro? Standard methods include soak testing in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 37°C and testing across a spectrum of pH values to simulate different biological environments. Key performance indicators include monitoring changes in electrical impedance, optical transparency (for optoelectronics), and mechanical properties over extended periods [1] [5].

4. What is corrosion-triggered delamination? This is a critical failure mechanism where body fluids diffuse along the interface between a metal (like an electrode or wire) and its polymer encapsulation. This weakens adhesion and promotes corrosion at the metal surface, leading to the progressive delamination of the polymer layer. This process creates pathways for further fluid ingress, accelerating device failure [5].

5. Are rigid or flexible encapsulation materials better for long-term implantation? The field is shifting towards soft and flexible materials. Rigid materials (like epoxy or titanium housings) have a high mechanical mismatch with soft tissues, which can cause inflammation, fibrotic encapsulation, and device failure. Flexible and stretchable materials better match tissue mechanics, promoting better integration and reducing immune responses for more stable long-term performance [7] [6].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Diagnosing Encapsulation Failure

Symptom: Sudden or Gradual Increase in Device Power Consumption

- Potential Cause: Current leakage through compromised encapsulation.

- Diagnosis:

Symptom: Unstable Electrode Impedance or Loss of Signal Fidelity

- Potential Cause: Corrosion of electrode surfaces or underlying conductive traces.

- Diagnosis:

Symptom: Visible Delamination or Discoloration Under Microscopy

- Potential Cause: Corrosion-triggered delamination or water-induced swelling at material interfaces.

- Diagnosis:

Symptom: Complete Wireless Communication or Power Transfer Failure

- Potential Cause: Catastrophic failure of internal electronics due to water and ion ingress, leading to short circuits or corrosion of antenna elements.

- Diagnosis:

Experimental Data & Material Comparisons

Table 1: Performance of Encapsulation Materials in Harsh Environments

Performance comparison of various encapsulation materials based on recent research.

| Material | Key Characteristic | Failure Timeline (pH 1.5) | Optical Transmittance (%) | Young's Modulus | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oil-Infused Elastomer | Liquid perfluoropolyether (Krytox) barrier | >2 years (projected) [1] | ~86.7 [1] | ~MPa range [1] | Potential oil depletion over time |

| Silicone Elastomer (PDMS) | Standard flexible encapsulant | <19 days [1] | ~95.3 [1] | ~MPa range [7] | High water vapor permeability [5] |

| Parylene C | Conformal thin-film coating | <1.5 days [1] | ~87.4 [1] | ~GPa range [1] | Prone to cracking under strain; pin-hole defects [6] |

| Epoxy Resin | Rigid, high-performance seal | N/A (commonly used in GI tract) [1] | Opaque or Low [1] | >GPa [1] | High stiffness causes mechanical mismatch with tissues [1] |

| Liquid Metal | Ultralow water permeability | Susceptible to low pH corrosion [1] | ~0.01 [1] | Liquid | Electrically conductive, not transparent [1] |

Table 2: Common Failure Mechanisms and Diagnostic Signals

A summary of key failure mechanisms, their causes, and how to detect them.

| Failure Mechanism | Root Cause | Observable/Diagnostic Signal |

|---|---|---|

| Current Leakage | Water and ion penetration through encapsulation [5] [6] | Increased power consumption; drop in insulation resistance [8] |

| Corrosion | Electrochemical reactions at metal surfaces exposed to ions and water [5] | Increased electrode impedance; visible pitting or dissolution on metal [5] |

| Corrosion-Triggered Delamination | Diffusion of body fluids into the metal-polymer interface, weakening adhesion [5] | Visible gaps at interfaces; device malfunction without bulk material failure [5] |

| Fibrotic Encapsulation | Chronic immune response to a stiff or bio-incompatible device [7] | Degraded signal-to-noise ratio in recordings; reduced stimulation efficacy over weeks/months [7] [8] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Sylgard-184 (PDMS) | A two-part silicone elastomer; the standard for flexible encapsulation research due to its biocompatibility and ease of processing [5]. |

| Krytox Oils | A family of perfluoropolyether (PFPE) fluids; used in liquid-based encapsulation for their ultralow water diffusion coefficient [1]. |

| Parylene C | A vapor-deposited polymer that provides a conformal, pin-hole free coating; often used as a benchmark thin-film barrier [1] [6]. |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | Standard solution for in vitro soak testing to simulate the ionic environment of the body [1] [5]. |

| Iridium Oxide | A conductive coating applied to electrodes to enhance charge storage capacity and improve stability during electrical stimulation [8]. |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Liquid-Based Encapsulation

Objective: To assess the long-term barrier performance of an oil-infused elastomer encapsulation for a wireless bioelectronic device under accelerated aging conditions.

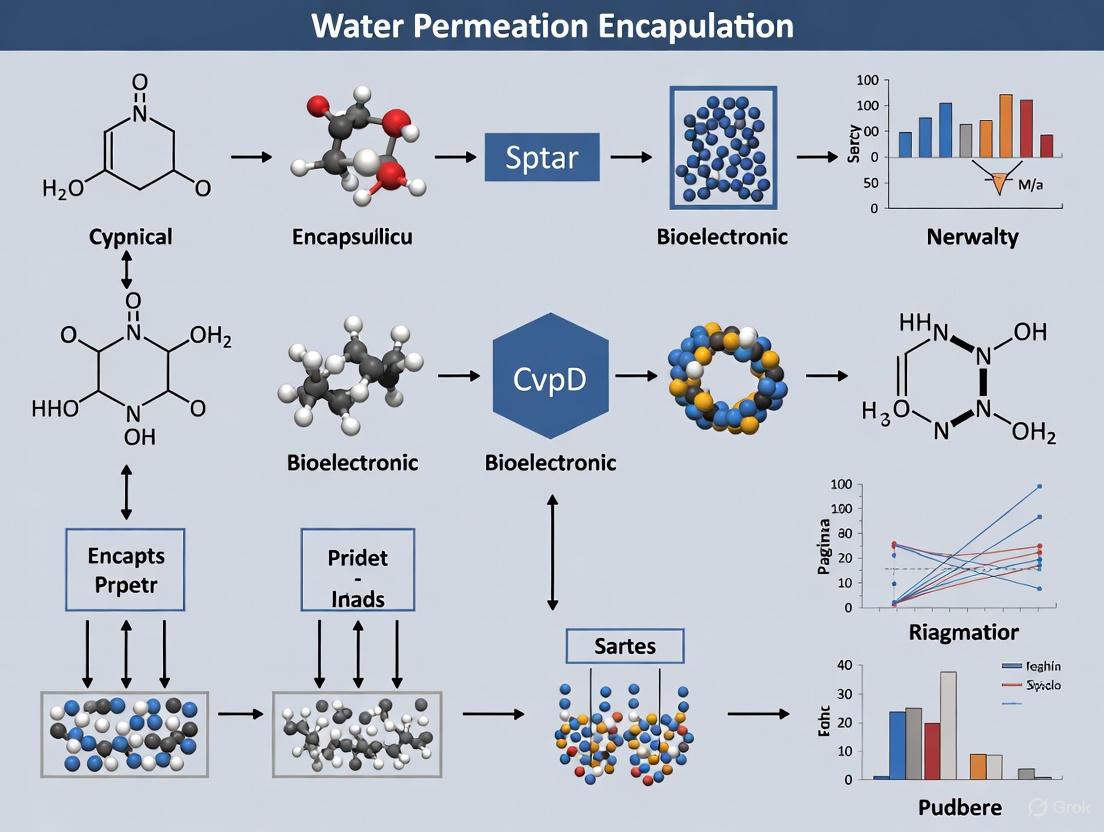

Workflow Overview: The diagram below outlines the key steps in this encapsulation and validation protocol.

Detailed Methodology:

Fabricate Roughened Elastomer:

- Prepare a 100 µm thick layer of PDMS (e.g., Sylgard-184) using a molding technique with abrasive paper as a template. This creates a surface with a high arithmetical mean height (Sa ~4.7 µm) to mechanically lock the infusion liquid [1].

Device Encapsulation:

- Place the bioelectronic device (e.g., a near-field communication antenna or wireless optoelectronic device) between two layers of the rough elastomer film, creating a sandwich structure with rough surfaces facing outward [1].

- Cure the assembly at ambient temperature overnight [1].

- Cut the encapsulated device to the desired shape using an ultraviolet (UV) laser. Optimize parameters (e.g., 30 kHz frequency, 100 mm/s speed) to create a rougher cut edge, which helps minimize the side-edge failure path [1].

- Infuse Krytox oil (a synthetic perfluoropolyether fluid) with a thickness of approximately 15 µm into the rough surface structures of the elastomer using a vacuum desiccator [1].

In Vitro Testing:

- Submerge the encapsulated devices in buffer solutions with pH values representing target biological environments (e.g., pH 1.5 for stomach acid, pH 7.4 for physiological conditions, pH 9.0 for alkaline wounds) [1].

- Maintain the soak tests at 37°C and periodically monitor key device functions. For a wireless optoelectronic device, this includes verifying robust wireless operation and maintaining high optical transparency. For NFC devices, monitor the quality factor or power transfer efficiency [1].

Failure Analysis:

- After testing, use scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to inspect for signs of delamination, corrosion, or cracking, particularly at the critical device edges and metal-polymer interfaces [5].

- Perform electrochemical impedance spectroscopy on electrodes to quantify any degradation caused by exposure [8].

Failure Mechanism Diagram: Corrosion-Triggered Delamination

The following diagram illustrates the key process of corrosion-triggered delamination, a major failure mode at the metal-polymer interface.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does our PDMS-encapsulated bioelectronic sensor fail after prolonged exposure to biological fluids?

A: The failure is primarily due to nonspecific adsorption of proteins and absorption of small hydrophobic molecules from the biological fluid into the PDMS matrix [9]. PDMS is inherently hydrophobic, which causes proteins to adhere to its surface, potentially fouling sensors and affecting analyte transport [9]. Furthermore, its porous, absorbent polymer network can sequester small drug-like molecules, altering the local chemical environment and leading to inaccurate readings in drug development applications [9]. While oxygen plasma treatment can temporarily make the surface hydrophilic, PDMS typically undergoes fast hydrophobic recovery within minutes to hours, restoring its fouling characteristics [9].

Q2: Our epoxy-encapsulated implants show reduced performance in humid environments. What is the underlying mechanism?

A: Epoxy resins are susceptible to water absorption, which can lead to several issues [10]. Water molecules diffuse into the polymer matrix, causing:

- Plasticization: Water acts as a plasticizer, reducing the epoxy's stiffness and strength, which can compromise mechanical integrity [10] [11].

- Swelling: The absorbed water induces swelling stresses, potentially leading to microcracks or delamination from the substrate [10].

- Chemical Degradation: In severe cases, especially at elevated temperatures or in alkaline conditions, hydrolysis can occur, breaking the polymer chains and permanently degrading the epoxy [11] [10]. Studies have shown that immersion in alkaline solutions can cause a tensile strength retention of as low as 14% [11].

Q3: We use Parylene C for its excellent barrier properties. In what high-temperature situations might it be unsuitable?

A: While Parylene C offers outstanding barrier performance at room temperature, its properties can degrade at elevated temperatures. Although fluorinated versions like Parylene AF-4 maintain excellent barrier performance after exposure to 300°C, all parylene films have a defined thermal stability window [12]. Exposure to temperatures approaching or exceeding this window during processes like soldering or sterilization can lead to:

- Structural Changes: Increased crystallinity or oxidation, which can alter the mechanical properties of the coating [12].

- Barrier Degradation: A potential increase in the Water Vapor Transmission Rate (WVTR), reducing its effectiveness as a moisture barrier [12]. For the highest temperature applications, Parylene AF-4 is a more robust choice [12].

Q4: Why can't we use silicone (PDMS) for creating a waterproof seal against water vapor?

A: Silicone rubber is an excellent barrier to liquid water but has extremely high permeability to water vapor and many gases [13]. Its polymer matrix has a large "free volume," which allows vapor molecules like oxygen and water vapor to easily migrate through it. Its water vapor permeability can be five to six orders of magnitude higher than that of a material like Teflon, making it unsuitable for applications requiring an effective seal against atmospheric moisture [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Rapid Biofouling of PDMS-Based Devices

Symptoms: Signal drift, reduced sensitivity, or clogging of microfluidic channels when used with biological samples.

Root Cause: The hydrophobic nature of PDMS causes rapid, nonspecific protein adsorption [9].

Solutions:

- Surface Hydrophilization: Treat the PDMS surface with oxygen plasma. Note: This is a temporary solution, as hydrophobic recovery occurs quickly [9].

- Permanent Surface Grafting: After plasma activation, graft hydrophilic polymers (e.g., polyethylene glycol) to the surface to create a non-fouling, brush-like layer [9].

- Rigid Coating Application: Apply a thin, rigid coating (e.g., a photo-sensitive thiolene resin) over PDMS structures. This has been shown to reduce deformation by 70% and may limit molecular absorption [9].

Problem: Epoxy Coating Failure in Cyclic Humidity/Temperature Environments

Symptoms: Coating blistering, loss of adhesion to the metal substrate, or hazy/cloudy appearance.

Root Cause: Water absorption leads to plasticization, swelling, and hydrolysis. Thermal cycling creates repeated expansion/contraction stress, causing fatigue failure [14] [10].

Solutions:

- Optimize Curing: Ensure the epoxy is fully cured according to manufacturer specifications, as a higher crosslink density can reduce water absorption [10].

- Environmental Control: Perform installation and curing in controlled conditions (ideally 60-80°F / 15-27°C and relative humidity below 85%) [14].

- Utilize Protective Topcoats: Apply a UV-resistant aliphatic topcoat if UV exposure is a concern, or a specialized sealant for chemical resistance [14].

- Material Selection: For environments with large temperature swings, select more flexible epoxy formulations designed to accommodate thermal movement [14].

Problem: Degradation of Parylene C Barrier in High-Temperature Sterilization

Symptoms: Increased moisture penetration and device failure after autoclaving or other high-temperature sterilization cycles.

Root Cause: Exposure to temperatures beyond the operational limit of Parylene C can degrade its crystalline structure and barrier properties [12].

Solutions:

- Material Upgrade: Switch to a parylene variant with higher thermal stability, such as Parylene AF-4, which demonstrates excellent barrier performance even after 300°C exposure [12].

- Process Validation: Characterize the specific sterilization process's temperature profile and ensure it remains within the safe zone for the chosen parylene type.

- Redundant Sealing: For critical applications, employ a "belt and suspenders" approach where the parylene-coated assembly is housed within a secondary gasketed enclosure [15].

The following tables summarize key performance limitations of the discussed materials, based on experimental data from the literature.

Table 1: Barrier Properties and Thermal Stability of Encapsulation Materials

| Material | Water Vapor Transmission Rate (WVTR) | Helium Transmission Rate (HTR) | Key Thermal Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDMS (Silicone) | Extremely High [13] | Very High [13] | Swells with organic solvents; properties change with temperature [9] [13] |

| Parylene C | 0.08 (g·mm)/(m²·day) [15] | Data not available in search | Performance degrades at high temperatures; inferior thermal stability vs. AF-4 [12] |

| Parylene AF-4 | 0.22 (g·mm)/(m²·day) at 25µm [15] | 12.18 × 10³ cm³ m⁻² day⁻¹ atm⁻¹ (after 300°C) [12] | Excellent thermal stability; maintains barrier after 300°C exposure [12] |

| Epoxy | ~0.94 (g·mm)/(m²·day) [15] | Data not available in search | Glass transition temperature (Tg) is a key limit; water absorption reduces Tg and mechanical properties [11] [10] |

Table 2: Resistance of Polymer Coatings to Saline Solution (0.9% NaCl)

| Polymer | Coating Method | Layer Thickness (µm) | Time Until Total Breakdown |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parylene C | CVD | 25 | > 30 days [15] |

| Epoxy (ER) | Dip Coating | 100 ± 25 | 6 hours [15] |

| Polyurethane (UR) | Dip Coating | 100 ± 12.5 | 6 hours [15] |

| Silicone (SR) | Dip Coating | 75 ± 12.5 | 58 hours [15] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Gravimetric Analysis for Water Absorption in Epoxy

Purpose: To determine the kinetics of water uptake and the equilibrium water content in an epoxy coating sample [10].

Materials:

- Epoxy sample (e.g., 10mm x 10mm x 1mm)

- Analytical balance (±0.1 mg)

- Immersion container with distilled water

- Oven for drying

- Desiccator

Methodology:

- Drying: Dry the epoxy sample in an oven until constant mass (wd) is achieved. Cool in a desiccator [10].

- Immersion: Immerse the sample in distilled water at a constant temperature (e.g., 23°C, 40°C, 60°C) [10].

- Weighing: At regular time intervals, remove the sample, wipe off surface water with filter paper, and weigh immediately (wt) [10].

- Calculation: Calculate the water uptake Mt (%) at each time point using: ( Mt = \frac{wt - wd}{wd} \times 100 ) [10].

- Data Fitting: Plot Mt versus the square root of time. Use models (e.g., Fickian, Carter-Kibler) to analyze the diffusion behavior and determine the diffusion coefficient [10].

Protocol 2: Bubble Point Test for Membrane Integrity

Purpose: To perform a non-destructive test to verify the integrity and pore size of a membrane filter (e.g., Nylon) before and/or after use [16].

Materials:

- Membrane filter

- Bubble point test apparatus (capable of applying air pressure)

- Water to wet the membrane

Methodology:

- Wet the Membrane: Completely saturate the membrane with purified water. Ensure all pores are filled [16].

- Apply Pressure: Place the wetted membrane in the test apparatus and gradually increase the air pressure on the upstream side [16].

- Observe: Monitor the downstream side of the membrane for a continuous stream of air bubbles.

- Record Bubble Point: The pressure at which the first continuous stream of bubbles is observed is the "bubble point" [16].

- Interpretation: Compare the measured bubble point to the manufacturer's specification. A lower-than-expected bubble point indicates damaged or oversized pores, compromising the membrane's retention efficiency [16].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Encapsulation and Filtration Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Parylene AF-4 Dimer | High-temperature, high-performance conformal coating via CVD [12] | Superior thermal stability and UV resistance; more expensive than Parylene C [12]. |

| Hydrophilic Nylon Membrane (0.45 µm) | Sterile filtration of aqueous and organic solvents in sample preparation [16] | Inherently hydrophilic, high protein binding (~120 µg/cm²), and chemically inert [16]. |

| Oxygen Plasma System | Surface activation of PDMS for temporary hydrophilization or permanent grafting [9] | Parameters (power, time) must be optimized. Hydrophobic recovery begins immediately after treatment [9]. |

| Two-Part Structural Epoxy Adhesive | Bonding and encapsulating components in a humid environment [11] | Susceptible to hygrothermal ageing; verify reduction in Tg and modulus after environmental exposure [11]. |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: A generalized workflow for identifying and troubleshooting material limitations in encapsulation research.

FAQs on Soft Bioelectronic Encapsulation

1. Why is mechanical compliance so important for implantable bioelectronics?

The human body is composed of soft, dynamic, and continuously moving tissues. Implanted devices made from rigid materials create a mechanical mismatch, which can lead to inflammation, tissue damage, fibrosis (scar tissue formation), and eventual device failure. Soft and flexible encapsulation allows the device to conform and integrate seamlessly with its biological environment, minimizing these adverse responses and ensuring long-term functionality [17].

2. How can I quantitatively monitor water permeation through a flexible thin-film encapsulation in real-time?

A promising method involves using a wireless, battery-free flexible platform that leverages backscatter communication and magnesium (Mg)-based microsensors. Water permeation corrodes the Mg resistive sensor, which shifts the oscillation frequency of the sensing circuit. This frequency shift can be measured wirelessly to provide a real-time, quantitative measure of the Water Transmission Rate (WTR), both in vitro and in living tissue [18].

3. What are the options for encapsulating devices that need to operate in extreme pH environments, such as the stomach?

Conventional encapsulation materials like silicone elastomer or Parylene C often fail quickly in highly acidic or alkaline conditions. A recent development is a liquid-based encapsulation using an oil-infused elastomer. This approach has demonstrated robust protection for implantable wireless devices in environments ranging from pH 1.5 to pH 9, maintaining functionality for extended periods where other materials fail [1].

4. What are the key differences between reliability, stability, and durability in bioelectronic medicine?

These are distinct but interconnected concepts:

- Reliability is the probability a device functions as intended without failure over a specified time.

- Stability is the ability to maintain functional and structural properties over time, resisting degradation from environmental or biological fluctuations.

- Durability refers to physical resilience and the ability to withstand external stresses like mechanical deformation without compromising function [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Unstable Device Performance Due to Water Ingress

Problem: Gradual degradation or failure of a soft implantable device, suspected to be caused by water vapor and ion permeation through the encapsulation.

Diagnosis and Solution:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome & Quantitative Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| 1. In-situ Verification | Integrate a wireless Mg-based microsensor into your device encapsulation. Use an external reader to monitor the sensor's oscillation frequency. | A decreasing frequency provides real-time, in-situ confirmation of water permeation and corrosion of the Mg sensor [18]. |

| 2. WTR Quantification | Apply an analytical model to convert the measured frequency shift into a Water Transmission Rate (WTR). | Obtain a quantitative WTR value (e.g., in g/m²/day). Effective encapsulation for bioelectronics requires very low WTR (≤ 10⁻⁴ g/m²/day) [18]. |

| 3. Material Selection | If WTR is too high, consider alternative encapsulation strategies. For extreme pH environments, evaluate an oil-infused elastomer system. | Soaking tests show oil-infused elastomers maintain device performance for nearly 2 years in pH 1.5 and 4.5 solutions, unlike conventional materials which fail within days [1]. |

Experimental Protocol: Fabricating and Testing Mg-based Water Permeation Sensors

- Substrate Preparation: Begin with a flexible 5-µm thick polyimide (PI) substrate.

- Metal Deposition: Deposit a ~20 nm Titanium (Ti) adhesion layer, followed by a ~200 nm thick Mg film via thermal evaporation or DC sputtering.

- Patterning: Use UV photolithography followed by wet or dry etching to pattern the Mg layer into the desired sensor designs (e.g., stripes or serpentines).

- Encapsulation: Apply the thin-film encapsulation (TFE) you wish to test over the sensor.

- In-vitro Testing: Immerse the sensor in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 37°C while monitoring the frequency via a wireless reader. The corrosion of Mg to Mg(OH)₂ will cause a measurable frequency drop [18].

Issue 2: Encapsulation Failure in Extreme pH Environments

Problem: Implantable bioelectronics, such as those for gastrointestinal monitoring, fail rapidly due to corrosion in highly acidic or alkaline conditions.

Diagnosis and Solution:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome & Quantitative Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Material Assessment | Test current encapsulation (e.g., silicone elastomer, Parylene C) in the target pH buffer. Monitor device performance (e.g., wireless signal strength). | Conventional materials like silicone may fail completely within 1.5-19 days in pH 1.5 solution [1]. |

| 2. Switch to Liquid Encapsulation | Implement an oil-infused elastomer encapsulation. Sandwich the device between two layers of roughened PDMS (~100 µm), infuse with a 15 µm layer of Krytox oil, and seal the edges with optimized laser cutting. | The encapsulation should maintain high optical transparency (~87% transmittance) and device functionality for up to 2 years in acidic conditions [1]. |

| 3. Biocompatibility & In-vivo Validation | Perform immunohistochemistry studies in an animal model (e.g., mice) to confirm biocompatibility and test the encapsulated device's operation in a freely moving animal. | The encapsulation should show no significant foreign body response and the device should maintain robust wireless operation for at least 3 months post-implantation [1]. |

Workflow for Liquid-based Encapsulation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Polyimide (PI) | A common flexible polymer substrate for fabricating thin-film devices and sensors, providing mechanical support and electrical insulation [18]. |

| Magnesium (Mg) Thin Films | Serves as the active material in water permeation sensors. Its corrosion in the presence of water produces a measurable change in electrical resistance or wireless circuit frequency [18]. |

| Parylene C | A common polymer used for conformal coating of bioelectronics. It offers good barrier properties and biocompatibility in neutral pH environments, but can fail in extreme pH [1]. |

| Silicone Elastomer (e.g., PDMS) | A widely used soft and stretchable encapsulation material. It is often the base material for more advanced systems, such as oil-infused elastomers [1]. |

| Krytox Oil (PFPE) | A perfluoropolyether fluid with an ultralow water diffusion coefficient. It is infused into roughened elastomer surfaces to create a slippery, liquid-based barrier against water and ion penetration, even in extreme pH [1]. |

| Epoxy Resin | A rigid encapsulation material often used for implants in harsh environments like the gastrointestinal tract. Its high modulus and thick geometry limit its use in soft bioelectronics [1]. |

Wireless Water Permeation Sensing Principle.

Innovative Encapsulation Solutions: From Liquid Barriers to Conformal Coatings

This technical support center provides essential guidance for researchers working on advanced encapsulation strategies for implantable bioelectronics. The content focuses on liquid-based encapsulation, specifically oil-infused elastomers, which represent a breakthrough in protecting sensitive electronic components from water and ion permeation across challenging pH environments. These materials combine superior barrier performance with the mechanical compliance required for integration with soft, dynamic biological tissues.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: Why is my current encapsulation failing in acidic or alkaline biological environments?

- Answer: Conventional encapsulation materials like silicone elastomer or Parylene C are often designed for near-neutral pH conditions (pH ~7.4) and lack the chemical stability for extended periods in extreme pH. The oil-infused elastomer encapsulation uses a synthetic perfluoropolyether (PFPE) fluid, which provides exceptional stability and barrier performance across a broad pH range (1.5 to 9.0), making it suitable for the gastrointestinal tract (acidic) and chronic wounds (alkaline) [1].

FAQ 2: My encapsulated device has failed at the cut edges. How can I improve edge sealing?

- Answer: The side edges created during cutting are potential failure points as they lack the rough microstructure to retain the oil. To mitigate this:

- Optimize Laser Cutting: Use a UV laser with specific parameters to create a rougher edge surface that better retains the oil. Parameters of 30 kHz frequency and 100 mm/s speed have been shown to be effective without causing excessive burning [1].

- Sandwich Structure: Ensure the bioelectronic device is fully encapsulated between two rough elastomer layers with the infused oil, creating a sealed environment [1].

- Answer: The side edges created during cutting are potential failure points as they lack the rough microstructure to retain the oil. To mitigate this:

FAQ 3: How can I verify the barrier performance of my encapsulation in real-time?

- Answer: You can integrate a wireless, battery-free sensing platform that uses magnesium (Mg) microsensors. As water permeates the encapsulation, the Mg corrodes, changing its electrical resistance. This resistance shift can be wirelessly monitored via a backscatter communication system, providing real-time, quantitative data on water permeation [19].

FAQ 4: I need a transparent encapsulation for my optoelectronic device. Will this method work?

- Answer: Yes. A key advantage of the oil-infused elastomer is its high optical transparency. The combination of a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) elastomer and the infused oil maintains an average optical transmittance of 86.67% across the visible wavelength range (380–700 nm), making it highly suitable for optoelectronic implants like wireless stimulators or sensors [1].

FAQ 5: Is the oil-infused elastomer biocompatible for long-term implantation?

- Answer: Yes. In vivo immunohistochemistry studies have demonstrated the biocompatibility of the oil-coated elastomer material. Furthermore, encapsulated wireless optoelectronic devices have maintained robust operation over 3 months of implantation in freely moving mice, confirming both biocompatibility and functional stability [1] [20].

Experimental Protocols & Performance Data

Protocol: Fabrication of Oil-Infused Elastomer Encapsulation

The following workflow details the preparation of a device encapsulated with an oil-infused elastomer.

Quantitative Performance Data

The table below summarizes the key performance metrics of oil-infused elastomer encapsulation compared to other common materials.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Encapsulation Materials

| Material | Avg. Optical Transmittance (Visible Light) | Failure Strain | Young's Modulus | Longevity in Acidic pH (pH 1.5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oil-Infused Elastomer | 86.67% [1] | ~100% [1] | ~MPa range [1] | >550 days (NFC antenna) [1] [20] |

| PDMS Elastomer | 95.33% [1] | ~100% [1] | ~MPa range [1] | Failed or lost >20% performance in 1.5-19 days [1] |

| Parylene C | 87.43% [1] | <5% [1] | ~GPa range [1] | Failed or lost >20% performance in 1.5-19 days [1] |

| Liquid Metal | 0.01% [1] | N/A | N/A | Susceptible to corrosion in low pH [1] |

Protocol: Real-Time Monitoring of Water Permeation

For quantitative assessment of encapsulation barrier performance, follow this protocol using magnesium-based sensors.

Principle: Water permeation corrodes a magnesium (Mg) resistive sensor, increasing its resistance. This resistance is part of a circuit that shifts the oscillation frequency of a wireless backscatter tag, allowing for remote monitoring [19].

Steps:

- Fabricate Mg Sensor: Deposit a ~200 nm thick Mg film with a 20 nm Titanium (Ti) adhesion layer onto a flexible polyimide substrate. Pattern the film into a specific geometry (e.g., serpentine) using photolithography and etching [19].

- Integrate with Circuit: Connect the Mg sensor as the resistance (

R_set) in a square-wave oscillator circuit that controls an RF switch connected to a flexible dipole antenna. - Wireless Interrogation: Expose the encapsulated sensor to an aqueous environment (e.g., PBS buffer). Use an external interrogator (reader) to power the tag via radio waves and monitor the frequency of the backscattered signal.

- Data Analysis: Track the decreasing oscillation frequency (

f_osc) over time. Use a pre-calibrated model to correlate the frequency shift with the sensor's resistance change and calculate the Water Transmission Rate (WTR) [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Materials for Oil-Infused Elastomer Encapsulation Research

| Material / Reagent | Function / Role | Specific Example / Properties |

|---|---|---|

| PDMS (Polydimethylsiloxane) | Base elastomer that provides the mechanical scaffold and stretchability. | A soft polymer (Young's modulus in the MPa range) that can be textured to create a rough, micro-structured surface [1]. |

| Krytox Oil | The infused liquid that provides the primary barrier to water and ion penetration. | A synthetic perfluoropolyether (PFPE) fluid characterized by an ultralow water diffusion coefficient [1]. |

| Mg (Magnesium) Thin Film | A sensing element for real-time, wireless monitoring of water permeation through the encapsulation. | ~200 nm thick film; corrodes predictably in the presence of water to Mg(OH)₂, changing its electrical resistance [19]. |

| NFC Antenna | A standard component of implantable bioelectronics for wireless power transfer and data communication, used for testing encapsulation performance. | Used to demonstrate long-term operational stability of the encapsulation under accelerated aging conditions [1]. |

| Titanium (Ti) Adhesion Layer | A thin film layer used to improve the adhesion of Mg to polymer substrates during microfabrication. | Typically ~20 nm thick, deposited via sputtering or thermal evaporation before Mg deposition [19]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What makes PFPE-based encapsulation a superior choice for implantable bioelectronics, especially in challenging biological environments?

PFPE fluids exhibit exceptional barrier properties against water and ion permeation, which is critical for the long-term stability of implantable bioelectronics. Their molecular structure provides remarkable chemical inertness, resisting attack even in highly acidic (e.g., pH 1.5, simulating stomach acid) or alkaline (e.g., pH 9.0, simulating chronic wound environments) conditions [21]. Furthermore, when infused into roughened elastomers, they form a slippery, stable layer that significantly reduces water and ion penetration. This liquid-based encapsulation approach has demonstrated functionality in vivo for up to 3 months in freely moving mice and year-long stability in accelerated in vitro soaking tests, outperforming conventional materials like silicone elastomer or Parylene C, which can fail within days under similar acidic conditions [21].

Q2: My current encapsulation (e.g., Parylene C) fails rapidly in extreme pH environments. What key material properties should I prioritize for such applications?

For extreme pH environments, you should prioritize the following material characteristics:

- Chemical Inertness: The encapsulation material must resist hydrolysis and chemical attack from both high concentrations of H⁺ (acidic) and OH⁻ (alkaline) ions. PFPE fluids are renowned for their exceptional chemical stability across a wide pH spectrum [21].

- Ultralow Water Permeability: The primary failure mechanism is often water vapor transmission. Materials with ultralow water diffusion coefficients are essential. PFPE oils, such as Krytox, possess this property [21].

- Mechanical Compliance: The encapsulation must be flexible and stretchable to withstand the dynamic movements of organs and tissues without cracking. A Young's modulus in the MPa range (matching soft biological tissues) is ideal, as opposed to the GPa range of rigid epoxies [21].

- Optical Transparency: For bioelectronics that incorporate optical sensing or stimulation (e.g., optoelectronics), high optical transmittance in the visible wavelength range is necessary. Oil-infused elastomers can maintain an average transmittance of over 85% [21].

Q3: How does the surface roughness of an elastomer contribute to the effectiveness of a liquid-based encapsulation system?

Surface roughness is not a flaw but a design feature in this context. A micro-roughened elastomer surface (with an arithmetical mean height, Sa, of ~4.7 µm) acts as a microscopic network of reservoirs that physically lock the PFPE oil in place via capillary forces and surface interactions [21]. This prevents the lubricating fluid from being squeezed out or de-wetting under mechanical stress, ensuring a continuous and stable barrier layer. Without this roughened structure, the liquid layer would be unstable and prone to failure.

Q4: Are there any biocompatibility concerns with using PFPE fluids and roughened elastomers in chronic implants?

In vivo studies have demonstrated the biocompatibility of the oil-infused elastomer material. Immunohistochemistry studies in mice implanted with devices encapsulated using this strategy showed robust operation over 3 months without significant adverse immune responses, confirming the material's suitability for chronic implantation [21]. As with any implantable material, rigorous sterilization and evaluation according to relevant ISO standards are recommended before clinical translation.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Inconsistent Encapsulation Performance and Premature Failure at the Edges

- Symptoms: Device failure occurs much earlier than expected, often starting from the cut edges of the encapsulated device. Electrical measurements show a rapid increase in leakage current.

- Root Cause: The side edges, created during the cutting process, lack the micro-roughened structure present on the top and bottom surfaces. This smooth edge offers a pathway for water and ions to wick into the device sandwich structure [21].

- Solution:

- Optimize Laser-Cutting Parameters: The laser-cutting process should be tuned to create a rougher edge surface that can better retain the PFPE fluid.

- Validated Parameter Set: Use a UV laser with a frequency of 30 kHz and a speed of 100 mm/s. Avoid lower frequencies (e.g., 25 kHz) which can cause excessive burning and uneven surfaces [21].

- Post-Cutting Inspection: Use scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to verify the morphology of the cut edges and ensure consistency.

Problem: Delamination of Encapsulation Layers Under Cyclic Mechanical Strain

- Symptoms: The bonded layers of the encapsulation begin to separate after repeated stretching or bending, compromising the barrier.

- Root Cause: Inadequate bonding strength between the elastomer layers that form the "sandwich" around the bioelectronic device.

- Solution:

- Surface Activation: Prior to bonding, treat the smooth inner surfaces of the PDMS elastomer films with oxygen plasma. This creates reactive silanol groups on the surface.

- Bonding Protocol: After plasma treatment, bring the activated surfaces into immediate conformal contact. Cure the assembled structure at ambient temperature overnight to form strong, permanent Si-O-Si bonds [21].

- Mechanical Testing: Perform peel tests on sample sandwiches to validate bond strength before proceeding with functional devices.

Problem: Cloudy Encapsulation Leading to Poor Optical Transmission for Optoelectronic Implants

- Symptoms: The final encapsulated device has reduced optical clarity, hindering the performance of optical components.

- Root Cause: Incomplete infusion of the PFPE oil into the elastomer's rough microstructure, leaving air pockets that scatter light. Alternatively, the oil layer may be too thick.

- Solution:

- Ensure Full Vacuum Infusion: Perform the oil infusion process in a vacuum desiccator. Hold the vacuum for a sufficient duration (e.g., 30-60 minutes) to ensure all air is evacuated from the rough surface and replaced with the PFPE fluid [21].

- Control Oil Thickness: After infusion, wipe the surface with a lint-free cloth to remove excess oil and achieve a thin, uniform layer. The study successfully used an oil thickness of 15 µm [21].

- Material Compatibility: Verify that all materials (elastomer, oil) are optically transparent. PFPE oils and PDMS typically have high inherent transparency.

Experimental Protocol: Fabricating a Liquid-Encapsulated Bioelectronic Device

This protocol details the method for creating an oil-infused elastomer encapsulation for a wireless implantable device, based on the approach validated in the research [21].

The following diagram illustrates the complete fabrication workflow.

Step-by-Step Methodology

Step 1: Preparation of Roughened Elastomer Substrate

- Materials: Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) base and cross-linker, abrasive paper (as a molding template).

- Procedure:

- Mix the PDMS precursor at a standard 10:1 base-to-cross-linker ratio.

- Pour the mixture onto the abrasive paper template and spin-coat or doctor-blade to achieve a uniform thickness of 100 µm.

- Cure the PDMS at the manufacturer's recommended temperature (e.g., 70°C for 1-2 hours).

- Peel the cured, roughened PDMS film from the template. Characterize the surface roughness; the target arithmetical mean height (Sa) is approximately 4.7 µm [21].

Step 2: Device Sandwiching and Bonding

- Procedure:

- Place the bioelectronic device (e.g., a near-field communication antenna or wireless optoelectronic device) onto the smooth side of one roughened PDMS film.

- Carefully place a second roughened PDMS film on top, with its smooth side facing the device, creating a sandwich structure.

- Critical Step: Activate the outer smooth surfaces of this sandwich with oxygen plasma to make them hydrophilic and reactive.

- Immediately bring the activated surfaces into conformal contact and apply slight pressure. Cure the assembly at ambient temperature overnight to form an irreversible bond [21].

Step 3: Laser Cutting and Shape Definition

- Equipment: Ultraviolet (UV) laser cutter.

- Procedure:

- Use a UV laser to cut the encapsulated device to its final shape.

- Validated Parameters: Set the laser frequency to 30 kHz and the cutting speed to 100 mm/s. This combination produces a sufficiently rough cut edge without causing excessive burning, which is crucial for edge-sealing [21].

Step 4: PFPE Oil Infusion

- Materials: Krytox GPL series PFPE oil (or equivalent).

- Procedure:

- Place the laser-cut device in a vacuum desiccator.

- Completely cover the device with the PFPE oil.

- Apply a vacuum for 30-60 minutes to evacuate air from the micro-roughness on the elastomer surface.

- Release the vacuum, allowing the oil to be infused into the porous rough structure. The target oil layer thickness is 15 µm [21].

- Wipe away any excess oil from the surface with a lint-free cloth.

Performance Validation and Testing Protocol

After fabrication, validate the encapsulation performance as outlined below.

1. In Vitro Soaking Test:

- Objective: To assess long-term barrier performance under accelerated conditions.

- Method: Immerse the encapsulated device in buffer solutions of varying pH (e.g., pH 1.5, 4.5, 7.4, and 9.0) and maintain at 37°C.

- Measurement: Periodically measure the device's performance, such as the quality factor (Q-factor) of a resonant antenna or wireless link efficiency. A performance drop of more than 20% is typically considered a failure point. The target is to maintain performance for over 1.5 years in acidic conditions and 1 year at physiological pH [21].

2. In Vivo Biocompatibility and Functionality Test:

- Objective: To evaluate biocompatibility and operational stability in a living organism.

- Method: Implant the device subcutaneously in an animal model (e.g., freely moving mice).

- Measurement:

- Biocompatibility: After 3 months, perform immunohistochemistry on the surrounding tissue to assess the immune response (e.g., presence of macrophages, fibrosis).

- Functionality: Continuously or periodically monitor the device's wireless operation throughout the implantation period [21].

Quantitative Data and Material Properties

| Material | Average Optical Transmittance (Visible Spectrum) | Failure Strain | Young's Modulus | Key Characteristics & Performance in Acidic pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oil-Infused Elastomer | 86.67% | ~100% | A few MPa | Maintains performance for nearly 2 years in pH 1.5 |

| PDMS Elastomer | 95.33% | ~100% | A few MPa | Fails rapidly in extreme pH without oil barrier |

| Parylene C | 87.43% | <5% | A few GPa | Loses >20% performance within 1.5-19 days in pH 1.5 |

| Polyimide (PI) | 7.70% - 71.22% | <5% | A few GPa | Low transparency; stiff and non-stretchable |

| Liquid Metal | ~0.01% | N/A | N/A | Electrically conductive; not transparent |

| Product / Type | Kinematic Viscosity at 20°C (cSt) | Vapor Pressure (torr) @20°C | Continuous Service Temp. Range (°C) | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Krytox PFPE Oils (Base for infusion) | Varies by grade (e.g., 150 - 1500) | Ultralow (e.g., ~10⁻¹¹) | -65 to +200+ | Base fluid for vacuum pumps, lubricants, and encapsulation [21] |

| OT 20 Grease | 35 | N/A | -50 to +70 | General purpose, low temperature |

| RT 15 Grease | 1300 | N/A | -20 to +250 | High temperature, low volatility |

| ZLHT Grease | 150 | N/A | -65 to +200 | Wide temperature range |

| AR 555 Grease | 1500 | 3.9 x 10⁻¹¹ | -20 to +250 | Low vapor pressure for high vacuum |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for PFPE-Based Encapsulation Research

| Item | Function / Role in Experiment | Specification / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PDMS | Base elastomer for creating the micro-roughened encapsulation substrate. | Use a standard two-part kit (e.g., Sylgard 184). Aim for a final thickness of 100 µm [21]. |

| Abrasive Paper | Template for molding the microscale rough surface onto the PDMS. | Varying grit sizes can be tested to achieve the target roughness (Sa ~4.7 µm) [21]. |

| Krytox PFPE Oil | The active barrier fluid infused into the rough PDMS surface. | A synthetic perfluoropolyether fluid with an ultralow water diffusion coefficient [21]. |

| Oxygen Plasma System | Activates PDMS surfaces for irreversible bonding of the sandwich structure. | Critical for creating strong bonds without adhesives that could compromise the barrier [21]. |

| UV Laser Cutter | Defines the final shape of the encapsulated device and creates sealed edges. | Must be capable of fine-tuning parameters (30 kHz, 100 mm/s) to create rough, non-burned edges [21]. |

| Vacuum Desiccator | Chamber for degassing and infusing the PFPE oil into the elastomer. | Ensures complete infiltration of oil into the micro-roughness, eliminating air pockets [21]. |

This technical support guide details the fabrication process for developing advanced liquid-encapsulated bioelectronic implants. This method is central to ongoing thesis research on preventing water and ion permeation, a critical challenge for the long-term reliability of implantable devices in the harsh ionic environment of the body [1]. The following sections provide a comprehensive, step-by-step protocol, accompanied by troubleshooting guides and FAQs, to assist researchers in replicating and optimizing this fabrication process.

Experimental Protocol: Core Fabrication Workflow

The following diagram outlines the complete fabrication workflow, from substrate preparation to the final oil infusion step.

Step 1: Molding the Roughened Elastomer Substrate

- Objective: Create a flexible elastomer film with a micro-rough surface to serve as a scaffold for locking the hydrophobic oil in place.

- Detailed Methodology:

- Template Preparation: Use abrasive paper as a template for the molding process. The grit size will determine the surface roughness, which is critical for oil retention [1].

- PDMS Preparation: Mix the PDMS base and curing agent according to the manufacturer's instructions. Degas the mixture in a vacuum desiccator to remove air bubbles.

- Molding and Curing: Pour the PDMS mixture onto the abrasive paper template. Cure at ambient temperature or in an oven according to the polymer's specifications, typically at 70°C for 1-2 hours.

- Demolding: Carefully peel the cured PDMS film from the template. The resulting film should have a thickness of approximately 100 µm and a micro-rough surface with an arithmetical mean height (Sa) of around 4.7 µm [1].

Step 2: Sandwiching the Bioelectronic Device

- Objective: Fully enclose the implantable bioelectronics within a protective elastomer shell.

- Detailed Methodology:

- Device Preparation: Ensure the bioelectronic device (e.g., NFC antenna, wireless optoelectronic device) is clean and functional.

- Assembly: Place the device between two layers of the rough PDMS film, ensuring the rough surfaces are facing outward.

- Bonding: Cure the PDMS "sandwich" at ambient temperature overnight to achieve a strong bond between the layers and fully encapsulate the device [1].

Step 3: Laser Cutting the Encapsulated Device

- Objective: Define the final shape of the implant without compromising the edge seal.

- Detailed Methodology:

- Laser Parameter Optimization: This is a critical step. Use an ultraviolet (UV) laser and optimize parameters to create rough cut edges, which help retain oil and prevent failure pathways [1].

- Recommended Parameters: A frequency of 30 kHz and a speed of 100 mm/s have been shown to create sufficiently rough edges without causing excessive burning [1].

- Cutting Process: Program the laser cutter to trace the desired outline of the device. The laser cutting not only shapes the device but also seals the edges of the PDMS sandwich.

- Laser Parameter Optimization: This is a critical step. Use an ultraviolet (UV) laser and optimize parameters to create rough cut edges, which help retain oil and prevent failure pathways [1].

Step 4: Infusing the Hydrophobic Oil

- Objective: Introduce a permanent liquid barrier that provides ultralow permeability to water and ions.

- Detailed Methodology:

- Oil Selection: Use a synthetic perfluoropolyether (PFPE) fluid such as Krytox oil, which is known for its high stability and ultralow water diffusion coefficient [1] [3].

- Infusion Process: Place the laser-cut device into a vacuum desiccator. Introduce the oil to ensure it fully wets the rough surfaces of the elastomer. The vacuum helps draw the oil into the micro-structured pores of the PDMS.

- Final Preparation: After infusion, a uniform oil layer with a thickness of about 15 µm should be present on the surface [1]. The device is now ready for testing and characterization.

Troubleshooting Guide: Fabrication Challenges and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete or uneven laser cutting [22] | Incorrect laser focus, insufficient power, excessive speed, dirty or misaligned optics. | Verify focal height is correct for material thickness. Clean the focusing lens and mirrors. Perform a ramp test to calibrate focus. Reduce cutting speed or increase laser power in 5% increments [22]. |

| Poor oil retention on elastomer surface | Inadequate surface roughness from molding step, incorrect oil viscosity, contamination on PDMS surface. | Verify the roughness parameters (Sa ~4.7 µm) of the molded PDMS using profilometry. Ensure the PDMS surface is clean and free of dust. Confirm compatibility between the Krytox oil and the elastomer [1]. |

| Device failure during in-vitro testing (early de-lamination) | Weak bonding between PDMS layers during sandwiching, incomplete curing of PDMS, smooth cut edges providing a path for water ingress. | Ensure PDMS layers are fully cured before bonding. Apply even pressure during the sandwiching process. Re-optimize laser parameters to create rougher cut edges that better retain the oil barrier [1]. |

| Optical transparency too low for application | Oil layer too thick, contamination in oil or between layers, use of non-transparent encapsulation materials. | Ensure the PDMS and oil layers are applied uniformly and are free of debris. Note that oil-infused elastomers can achieve an average optical transmittance of 86.67% in the visible spectrum [1]. |

| Laser cut edges are charred or uneven [22] | Laser power is too high, cutting speed is too slow, incorrect frequency setting. | Reduce laser power and/or increase cutting speed. Avoid using a frequency that is too low (e.g., 25 kHz) as it can cause excessive burning. Fine-tune parameters on scrap material first [1] [22]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is creating a rough edge during laser cutting critical for the long-term performance of the encapsulation?

A1: The side edges created by laser cutting are potential failure points for water permeation, as they lack the micro-rough structure of the top and bottom surfaces. Optimized laser parameters (e.g., 30 kHz, 100 mm/s) create a rougher edge morphology that helps lock in the hydrophobic oil, extending the device's functional lifetime in aqueous environments by blocking this permeation pathway [1].

Q2: How does this liquid-based encapsulation compare to traditional thin-film methods like Parylene C in terms of mechanical properties?

A2: Liquid-based encapsulation offers superior mechanical compliance for interfacing with soft tissues. The oil-infused elastomer has a Young's modulus on the order of a few MPa and can withstand failure strains of up to ~100%. In contrast, Parylene C is much stiffer, with a modulus in the GPa range and a failure strain of <5%, making it less ideal for applications with dynamic movement [1].

Q3: My laser is powered on and moves, but isn't cutting through the material. What should I check first?

A3: This is a common issue. Follow this diagnostic sequence [22] [23]:

- Focus: Confirm the laser beam is correctly focused on the material surface. An out-of-focus beam drastically reduces power density.

- Optics: Inspect and clean the focusing lens and mirrors. Even slight contamination can significantly weaken the output.

- Parameters: Double-check that your software settings for power, speed, and number of passes are appropriate for the material thickness.

- Air Assist: Ensure the air assist is functioning with sufficient pressure (e.g., 10-15 PSI) to clear molten debris and prevent scorching.

Q4: What is the evidence for the biocompatibility and long-term stability of this encapsulation strategy?

A4: Research has demonstrated both in-vitro and in-vivo performance. Immunohistochemistry studies in mice have shown the biocompatibility of the oil-coated elastomer. Furthermore, encapsulated wireless optoelectronic devices have maintained robust operation throughout 3 months of implantation in freely moving animals. In-vitro soaking tests in acidic solutions (pH 1.5) have shown durability for nearly 2 years [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function in the Protocol | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PDMS (Polydimethylsiloxane) | A flexible, biocompatible silicone elastomer that forms the primary encapsulation structure. | Provides a transparent, stretchable base. The micro-rough surface is key for oil retention [1]. |

| Krytox Oil (PFPE) | A hydrophobic perfluoropolyether fluid that creates the liquid barrier against water and ion permeation. | Selected for its ultralow water diffusion coefficient and chemical stability across a wide pH range [1] [3]. |

| Abrasive Paper | Serves as a molding template to create the micro-rough surface on the PDMS film. | The grit size determines the surface roughness parameters (Sa, Sp), which are critical for oil locking [1]. |

| UV Laser Cutter | Precisely shapes the final device and creates critical rough-edge morphology. | Parameters must be optimized (e.g., 30 kHz, 100 mm/s) to avoid smooth or charred edges [1]. |

| Vacuum Desiccator | Facilitates the infusion of oil into the porous, rough PDMS structure by removing air. | Ensures complete and uniform oil coverage without trapped air bubbles [1]. |

FAQs on Material Performance and Encapsulation

Q: Why is optical transparency important for implantable bioelectronic devices? Optical transparency is crucial for optoelectronic implants, such as those used for optogenetics or light-based therapy and sensing. It allows light to pass through the encapsulation film to interact with both the underlying device components and the biological tissues, enabling device functionality [1].

Q: What are the key mechanical properties an encapsulation layer should possess for use in implantable devices? The encapsulation should be stretchable and mechanically compliant to match the physical properties of surrounding tissues. This ensures the film remains intact during natural movements of body organs, providing long-term reliable protection without compromising structural integrity. A Young's modulus in the range of a few MPa is desirable to conformably integrate with soft tissues [1].

Q: My encapsulated device failed in an acidic environment. What could be the reason? Conventional encapsulation materials like silicone elastomer or Parylene C often lack resistance to extreme pH. They can fail completely or lose significant performance (e.g., >20% performance loss within 1.5-19 days) in highly acidic or alkaline conditions. A liquid-based encapsulation approach has been shown to provide superior barrier performance across a broad pH range (1.5 to 9) [1].

Q: How can I simultaneously achieve high optical transparency, stretchability, and a water barrier in an encapsulation material? Recent research demonstrates that a liquid-based encapsulation strategy using an oil-infused elastomer can meet these combined needs. One study reported an average optical transmittance of 86.67% in the visible wavelength, elastic deformation up to ~100% strain, and outstanding water resistance, maintaining device performance for nearly two years in vitro in acidic environments [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Device Failure Due to Water and Ion Permeation

| Observation | Investigation Question | Possible Root Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current leakage, performance degradation, or corrosion in implantable device [1] | Is the encapsulation material an effective barrier against water and ions? | Failure of conventional materials (e.g., PDMS, Parylene C) in challenging pH environments or under mechanical stress [1]. | Implement a liquid-based encapsulation. Adopt an oil-infused elastomer where a perfluoropolyether (PFPE) oil is infused into a roughened PDMS matrix, creating an ultralow water permeability barrier [1] [2]. |

| Device failure in highly acidic (e.g., stomach) or alkaline (e.g., chronic wounds) environments [1] | Was the encapsulation tested and validated for the specific pH of the target biological environment? | Material degradation or accelerated ion penetration (H⁺ or OH⁻) under extreme pH, for which many flexible encapsulations are not designed [1]. | Ensure encapsulation performance is verified across the entire relevant pH range (e.g., from pH 1.5 to 9). Select materials proven stable in these conditions [1]. |

Problem 2: Loss of Optical Transparency or Mechanical Durability

| Observation | Investigation Question | Possible Root Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diminished light transmission through the encapsulation layer [1] | Does the encapsulation material possess high intrinsic optical transparency? | Use of opaque or low-transparency materials (e.g., liquid metal with ~0.01% transmittance) for applications requiring optical signaling [1]. | Select materials with high optical transparency in the visible spectrum (380–700 nm). Oil-infused elastomers and Parylene C can offer over 85% average transmittance [1]. |

| Cracking or loss of encapsulation integrity during organ movement [1] | Does the mechanical modulus of the encapsulation match that of the surrounding tissue? | Use of materials with high Young's modulus (e.g., Parylene C or Polyimide in the GPa range) and low failure strain (<5%), making them too rigid for mobile organs [1]. | Use elastomeric materials (e.g., specific PDMS formulations) with a compliant Young's modulus (a few MPa) and high failure strain (approaching 100%) to ensure mechanical durability and stretchability [1]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication of Oil-Infused Elastomer Encapsulation

This methodology details the creation of a flexible, transparent, and durable encapsulation barrier for implantable bioelectronics [1].

1. Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| PDMS (Polydimethylsiloxane) | A transparent, biocompatible, and stretchable elastomer that forms the polymer matrix of the encapsulation [1]. |

| Abrasive Paper | Serves as a template to create micro-roughness on the PDMS surface, which is essential for locking the infusion oil in place [1]. |

| Krytox Oil (PFPE fluid) | A synthetic perfluoropolyether infusion fluid with an ultralow water diffusion coefficient, forming the core of the liquid barrier against water and ion penetration [1] [2]. |

| UV Laser Cutter | Used to precisely cut the encapsulated device to the desired shape while simultaneously creating controlled roughness on the side edges to minimize potential failure paths [1]. |

2. Step-by-Step Workflow

- Prepare Roughened Elastomer Film: Create a ~100 µm thick PDMS elastomer film using a molding technique with abrasive paper as a template. This process generates a surface with a defined arithmetical mean height (Sa ~4.7 µm) [1].

- Sandwich the Device: Place the implantable bioelectronic device between two layers of the rough elastomer film, ensuring the rough surfaces face outward [1].

- Cure the Assembly: Cure the PDMS-sandwiched device at ambient temperature overnight to bond the layers securely [1].

- Laser Cutting: Cut the encapsulated device to the desired shape using a UV laser. Optimize parameters (e.g., 30 kHz frequency, 100 mm/s speed) to create rougher edge surfaces that help retain the oil and enhance long-term performance [1].

- Oil Infusion: Infuse Krytox oil (to a thickness of ~15 µm) into the rough microstructures of the elastomer surfaces. This is typically done in a vacuum desiccator to ensure the oil penetrates and fills the pores effectively [1].

Protocol: Quantitative Characterization of Encapsulation Performance

1. Optical Transparency Measurement

- Objective: Quantify the light transmission through the encapsulation material.

- Method: Use a spectrophotometer to measure the optical transmission spectra across the visible wavelength range (380–700 nm). Report the average optical transmittance [1].

- Expected Results: As reported, PDMS elastomer (100 µm) can achieve ~95.33% transmittance, while the complete oil-infused elastomer system can maintain ~86.67% transmittance [1].

2. Mechanical Stretchability and Modulus Testing

- Objective: Determine the mechanical compliance and durability of the encapsulation.

- Method: Perform uniaxial tensile tests to obtain stress-strain curves. Measure the failure strain and calculate the Young's modulus from the linear elastic region [1].

- Expected Results: Elastomers like PDMS can show elastic deformation up to ~100% strain, with a Young's modulus in the MPa range, matching soft biological tissues [1].

3. Barrier Performance in pH Environments

- Objective: Validate the encapsulation's resistance to water and ions in biologically relevant pH conditions.

- Method: Soak encapsulated devices (e.g., wireless NFC antennas) in buffer solutions of varying pH (e.g., 1.5, 4.5, 7.4, 9.0) at physiological temperature. Monitor device performance metrics (e.g., quality factor, operational stability) over an extended period [1].

- Expected Results: Liquid-based encapsulation has demonstrated robust operation and high water resistance for periods up to several months or even years in vitro across the pH range of 1.5 to 9.0 [1].

Table 1: Comparative Optical and Mechanical Properties of Encapsulation Materials

| Material | Average Optical Transmittance (Visible Spectrum) | Failure Strain | Young's Modulus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oil-Infused Elastomer [1] | 86.67% | ~100% | A few MPa |

| PDMS Elastomer [1] | 95.33% | ~100% | A few MPa |

| Parylene C [1] | 87.43% | < 5% | A few GPa |

| Polyimide (PI) [1] | 7.70% - 71.22% | < 5% | A few GPa |

| Liquid Metal [1] | ~0.01% | Not Specified | Not Specified |

Table 2: Barrier Performance of Encapsulation in Acidic Environment (pH = 1.5)

| Encapsulation Strategy | Performance Outcome in Acidic Environment |

|---|---|

| Oil-Infused Elastomer [1] | Maintained device performance for nearly 2 years in vitro. |

| Conventional Silicone Elastomer [1] | Complete failure or >20% performance loss within 1.5-19 days. |

Experimental Workflow and Diagnostics

Oil-Infused Encapsulation Fabrication

Troubleshooting Encapsulation Failure

Ensuring Reliability: Troubleshooting Common Failure Points and Optimizing Performance

FAQs on Edge Protection and Encapsulation

FAQ 1: Why are the edges of a laser-cut encapsulation considered a critical weak point?

The cutting process creates edges that lack the specific protective structures present on the primary surfaces. For example, in advanced liquid-based encapsulation, the top and bottom surfaces may be engineered with rough structures to lock protective oils in place, a feature absent from the cut edges. These edges can provide a potential path for water and ion ingress, leading to device failure [1].

FAQ 2: What laser parameters are critical for optimizing the edge quality of a polymer encapsulation layer?

The key parameters are laser power, cutting speed, and frequency (pulse repetition). Research indicates that using a lower cutting speed and frequency generally creates a rougher edge surface, which can be beneficial for subsequent sealing processes. However, parameters that are too aggressive (e.g., a frequency of 25 kHz in one study) can cause excessive burning and uneven edges, making the process harder to control. An optimized setting (e.g., 30 kHz and 100 mm/s) can produce a controllably rougher edge that improves the effectiveness of the final seal [1].

FAQ 3: How can I quantitatively monitor the success of my encapsulation strategy in real-time?

A novel method involves integrating wireless, battery-free magnesium (Mg) microsensors into the device. When water permeates the encapsulation, it corrodes the Mg sensor, changing its electrical resistance. This resistance shift is wirelessly transmitted as a frequency change in a backscatter signal, allowing for real-time, in-situ quantification of the Water Transmission Rate (WTR) across the thin-film encapsulation [19].

FAQ 4: Besides edge sealing, what other surface optimization techniques improve laser cutting for encapsulation fabrication?

Advanced techniques like waterjet-guided laser cutting can significantly enhance cut quality. This method uses a waterjet to guide the laser, which simultaneously cools the material, reduces the heat-affected zone (HAZ), and minimizes issues like kerf taper, dross adherence, and surface roughness compared to conventional laser cutting [24]. Furthermore, standard optimizations include adjusting the laser's focus position and using appropriate assist gases (e.g., nitrogen for oxide-free cuts) to achieve smoother, cleaner edges [25] [26].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting Laser-Cut Edge Quality

| Problem | Root Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|