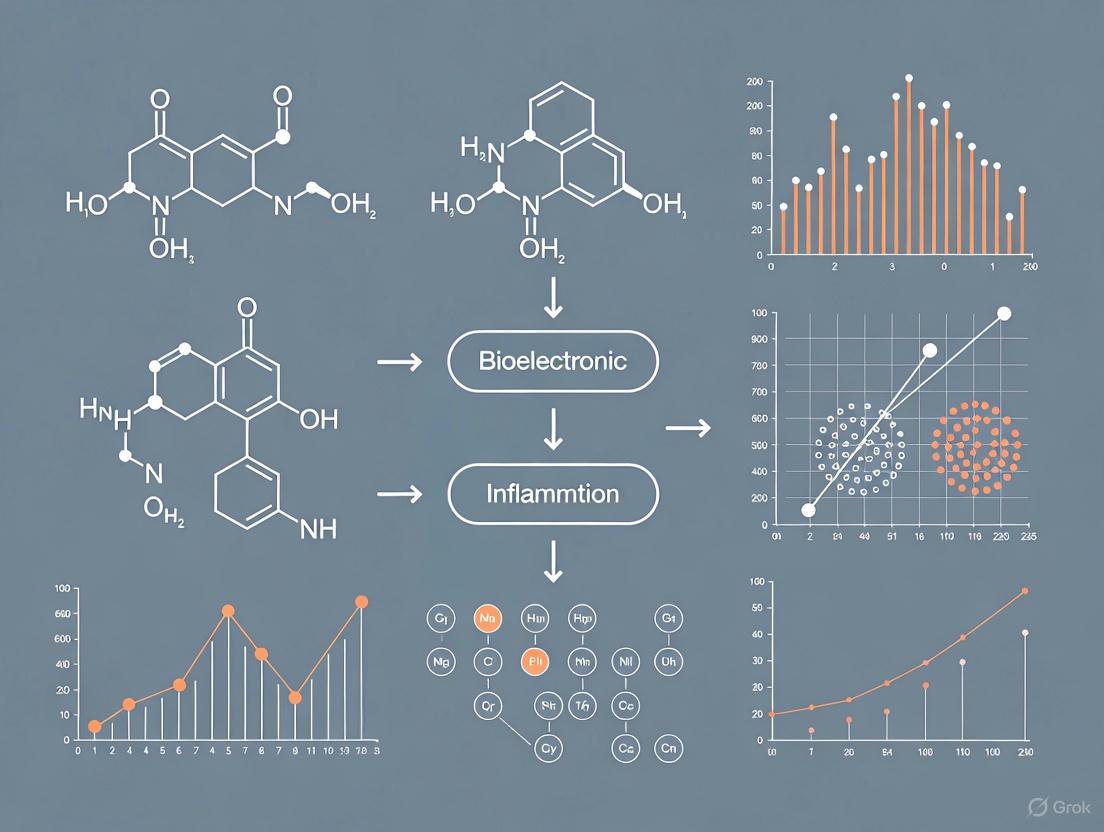

Strategies for Preventing Inflammation from Bioelectronic Implants: From Material Design to Clinical Management

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies to prevent inflammatory responses to bioelectronic implants, a critical challenge limiting their long-term reliability and clinical adoption.

Strategies for Preventing Inflammation from Bioelectronic Implants: From Material Design to Clinical Management

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies to prevent inflammatory responses to bioelectronic implants, a critical challenge limiting their long-term reliability and clinical adoption. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational biology of the Foreign Body Response (FBR), methodological advances in soft materials and device design, troubleshooting for existing failure modes, and validation through preclinical and clinical evidence. The scope spans from fundamental mechanisms and emerging material science—including soft electronics, bioactive interfaces, and novel paradigms like 'Circulatronics'—to practical optimization of implant systems and a forward-looking perspective on closed-loop, intelligent therapeutic platforms.

Understanding the Inflammatory Foe: The Biological Basis of the Foreign Body Response to Implants

The Foreign Body Response (FBR) is a universal immunological process that mammalian hosts initiate against implanted biomaterials, leading to the biological encapsulation of the implant [1]. This reaction presents a fundamental challenge in biomedical research, particularly for the performance and durability of implantable devices such as bioelectronic medicines [2]. When an object is implanted, the body's immune system does not recognize it as "self," activating complex signaling cascades designed to wall off and isolate the foreign material [1] [3]. This process can compromise device function by forming a thick fibrotic capsule that disrupts biosensing functions, causes patient discomfort, cuts off nourishment for cell-based implants, and ultimately leads to device failure [2]. Understanding and mitigating the FBR is therefore critical for advancing bioelectronic implants and other medical technologies.

The FBR Cascade: A Step-by-Step Breakdown

The Foreign Body Response is a coordinated sequence of immune events. The table below summarizes the key phases, their timelines, and the primary cellular players involved.

Table 1: The Temporal Progression of the Foreign Body Response

| Phase | Time Post-Implantation | Key Cells Involved | Major Events |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Adsorption | Seconds to Minutes | Plasma Proteins (Fibrinogen, Fibronectin) | Non-specific protein adsorption on the implant surface [2] |

| Acute Inflammation | Hours to Days | Neutrophils, Monocytes/Macrophages | Neutrophil infiltration and degranulation; Monocyte recruitment and differentiation into macrophages [2] [4] |

| Chronic Inflammation & FBGC Formation | Days to Weeks | Macrophages, Foreign Body Giant Cells (FBGC) | Macrophage fusion into FBGCs; Secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β) [2] [4] |

| Fibrosis & Encapsulation | Weeks to Months | Fibroblasts, Myofibroblasts | Collagen deposition; Formation of a fibrous capsule walling off the implant [2] [4] [3] |

Initial Protein Adsorption and Acute Inflammation

Immediately following implantation, non-specific protein adsorption occurs on the material's surface [2]. The composition of this protein layer is influenced by the biomaterial's properties and dictates subsequent immune recognition [2]. Fibrinogen is a prominently adsorbed protein that promotes inflammation by interacting with Mac-1 integrin on immune cells [2]. Within hours, the body mobilizes neutrophils, which are the primary cell type at the site for the first two days [2]. Neutrophils attempt to phagocytose the implant and release reactive oxygen species and proteolytic enzymes, which can cause damage to the implant itself [2].

Chronic Inflammation and Foreign Body Giant Cell Formation

As the response progresses, monocytes infiltrate the site and differentiate into macrophages [2]. These activated macrophages attempt to engulf the foreign material. When they cannot eliminate the large object, they fuse together to form Foreign Body Giant Cells (FBGCs), which can contain dozens of nuclei [2]. This chronic phase is characterized by high concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) and Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), which perpetuate the inflammatory state and initiate downstream signaling pathways such as NF-κB and JNK [2] [4]. Single-cell RNA sequencing has identified specific FBR-enriched macrophage subclusters that highly express these pro-fibrotic and pro-inflammatory mediators [3].

Fibrous Capsule Formation

The final and most detrimental stage for device functionality is fibrosis. Starting around day 7-14 post-implantation, fibroblasts appear in significant numbers and are activated to become myofibroblasts [2] [4]. These cells deposit dense collagen and other extracellular matrix components, eventually forming a avascular, fibrous capsule that completely walls off the implant from the surrounding tissue [2] [4] [3]. In studies, this capsule becomes clearly visible by day 14, with collagen deposition peaking and remaining substantial until at least day 90 [4]. Single-cell analyses have identified specific subpopulations of fibroblasts, such as Pi16+ and Mmp3+ fibroblasts, that are enriched in FBR conditions and demonstrate significant activity in the pro-fibrotic TGF-β signaling pathway [3].

The following diagram illustrates the key cellular events and signaling pathways in the FBR cascade:

Troubleshooting Common FBR Experimental Issues

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What are the primary immune cell types I should focus on when analyzing the FBR?

- A: Macrophages and fibroblasts are the two predominant cell types driving the response [3]. Macrophages are key for chronic inflammation and FBGC formation, while fibroblasts are responsible for the final fibrous encapsulation [2]. Single-cell RNA sequencing has further refined this, identifying specific pro-fibrotic subpopulations of both cell types [3].

Q: Why is my implant failing despite using a biocompatible material?

- A: The FBR is a universal process that occurs even to materials considered "biocompatible." The key is not necessarily to prevent the response entirely, but to modulate its intensity and outcome [1] [2]. The formation of a thick, avascular fibrous capsule is often the root cause of device failure, as it isolates the implant and can disrupt its function [2].

Q: How can I experimentally reduce the fibrotic capsule around my implant?

- A: Research indicates that targeting macrophage recruitment and activation is highly effective. Studies show that macrophage depletion can almost entirely prevent fibrosis [2]. Furthermore, disrupting specific pathways like Mac-1 integrin (which binds to adsorbed fibrinogen) or using anti-fouling polymers to minimize protein adsorption can significantly reduce capsule thickness [1] [2].

Q: I am working with a biodegradable polymer. How does degradation affect the FBR?

- A: The erosion and degradation behavior of polymers profoundly influences the FBR [1]. Degradation byproducts can create a sustained inflammatory stimulus, potentially leading to a more severe and prolonged FBR compared to non-degradable materials. It is critical to design polymers with degradation kinetics that do not overwhelm the local tissue's ability to clear the byproducts.

Advanced Experimental Guide: Utilizing Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

Modern techniques like single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) allow for unprecedented resolution in dissecting the FBR. The following workflow is based on a recent meta-analysis of mouse FBR studies [3].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for scRNA-seq Analysis of FBR

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Description | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Droplet-based scRNA-seq Platform | High-throughput single-cell capture and RNA barcoding. | 10X Genomics Chromium [3] |

| Bioinformatic Integration Tool | Harmonizes multiple datasets to identify universal signatures. | Seurat v5 with Harmony [3] |

| Cell-Cell Communication Analysis | Infers signaling interactions between cell subpopulations. | CellChat [3] |

| FBR Model | In vivo system to generate foreign body reaction tissue. | Subcutaneous silicone implant; Intra-abdominal silk sponge [3] |

Experimental Workflow:

- Model Establishment: Implant your biomaterial of interest in an appropriate animal model (e.g., subcutaneous pocket in mice) [3].

- Tissue Harvest: At predetermined time points (e.g., POD 5, 1 week, 2 weeks, 4 weeks, 6 weeks), explant the FBR tissue, including the implant and the surrounding capsule [3].

- Cell Processing: Dissociate the harvested tissue into a single-cell suspension. It is crucial to optimize the dissociation protocol to maintain cell viability and minimize stress-induced gene expression changes.

- scRNA-seq Library Preparation & Sequencing: Use a platform like 10X Genomics to prepare libraries and sequence them. The meta-analysis by Stanford researchers included data from 27 such mouse samples, totaling 108,826 cells [3].

- Bioinformatic Data Integration and Analysis:

- Integration: Use tools like Seurat to merge and harmonize data from different samples or studies. This corrects for technical batch effects and allows for cross-study comparison [3].

- Clustering & Annotation: Identify distinct cell populations (e.g., macrophages, fibroblasts, T cells) and then perform subcluster analysis to find unique subpopulations within these groups [3].

- Differential Expression: Identify genes that are significantly upregulated in FBR conditions compared to control tissues (e.g., "Surgery Control" or "Tissue Control") [3].

- Pathway & Interaction Analysis: Use gene ontology analysis and tools like CellChat to identify activated signaling pathways (e.g., TGF-β, TNF) and predict key cellular communication networks driving the FBR [3].

The following diagram visualizes this integrated analytical workflow:

Emerging Strategies to Modulate the FBR for Bioelectronic Implants

The ultimate goal in bioelectronics is to achieve seamless integration of the device with neural tissue. The following table summarizes key strategies informed by the FBR cascade.

Table 3: Strategic Approaches to Mitigate the Foreign Body Response

| Strategic Approach | Mechanism of Action | Example in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Material Surface Modification | Minimize initial protein adsorption, the first step of FBR. | Hydrophilic hydrogels in catheters reduce protein adhesion and clotting [5]. |

| Immunomodulatory Design | Actively steer the immune response toward a healing/tolerant phenotype. | Targeting Mac-1 integrin or using anti-fouling polymers to disrupt macrophage adhesion [1] [2]. |

| Mechanical Compliance | Reduce mechanical mismatch between device and tissue to minimize chronic inflammation. | Shift from rigid silicon/metal implants to soft, flexible electronics made from polymers and elastomers [6]. |

| Novel Implantation Techniques | Avoid major surgical trauma and preserve protective biological barriers. | "Circulatronics": microscopic, wireless, cell-guided electronics that self-implant via the bloodstream, crossing the blood-brain barrier without invasive surgery [7]. |

The Shift to Soft Bioelectronics

A major trend is the move away from rigid implants, which cause a significant mechanical mismatch with soft, dynamic tissues, leading to inflammation and fibrosis [6]. Next-generation devices are being fabricated from soft polymers, elastomers, and hydrogels with Young's moduli closer to biological tissues (1 kPa – 1 MPa) and bending stiffness below 10â»â¹ Nm [6]. These materials allow for better conformal contact with tissues, reducing micromotion and the ensuing chronic inflammatory stimulus [6].

Frontier Technology: Self-Implanting Bioelectronics

A revolutionary approach to bypassing the surgical FBR is "circulatronics." Researchers have developed microscopic, wireless electronic devices that are fused with living cells (e.g., monocytes) and injected into the bloodstream [7]. These cell-electronics hybrids use the cells' natural homing capabilities to cross the intact blood-brain barrier and autonomously implant in a target brain region, where they can provide electrical stimulation [7]. Because the electronics are camouflaged by living cells, they evade immune detection and do not trigger a significant FBR, offering a potential future where brain implants do not require invasive surgery [7].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is fibrotic encapsulation and why is it a major problem for bioelectronic implants? Fibrotic encapsulation is a foreign body reaction where the immune system forms a dense, collagenous scar tissue layer around an implanted device. This capsule acts as an electrical and chemical barrier, physically isolating the implant from the target neural tissue [8]. The consequences are significant: for recording electrodes, it causes signal degradation and a decreasing signal-to-noise ratio over time. For stimulating electrodes, it increases impedance and requires higher currents for effective stimulation, which can lead to tissue damage and reduced device longevity [9] [10].

Q2: What are the primary biological drivers behind this process? The process is driven by a complex immune response. Key players include:

- Macrophages: Immune cells that coordinate the response. Pro-inflammatory (M1) and pro-fibrotic (M2) subtypes are involved [11].

- Myofibroblasts: Activated fibroblasts that deposit excessive collagen, forming the fibrous capsule. Their activation is heavily influenced by mechanical forces and the cytokine TGF-β1 [12] [11].

- TGF-β1 (Transforming Growth Factor Beta 1): A pivotal pro-fibrotic cytokine. Its activation from a latent to an active state is often mechanically triggered by the stiffness mismatch between a rigid implant and soft tissue [12].

Q3: Besides biological factors, what other aspects of an implant can trigger fibrosis? The material and mechanical properties of the implant itself are critical triggers:

- Mechanical Mismatch: A large stiffness difference between a rigid implant (GPa) and soft neural tissue (kPa) generates chronic mechanical stress at the interface, promoting inflammation and fibroblast activation [10] [12].

- Implant-Tissue Interface: Non-adhesive implants that do not form a conformal bond with the tissue create micro-movements and spaces that allow for the infiltration of inflammatory cells, initiating the fibrotic cascade [8] [13].

Q4: What are the most promising new strategies to prevent fibrotic encapsulation? Recent research focuses on addressing the root causes:

- Adhesive Interfaces: Creating implants that form a tight, conformal bond with tissue, which prevents inflammatory cell infiltration and has been shown to prevent observable fibrosis for up to 12 weeks in animal models [8].

- Surface Softening: Using soft materials (∼2 kPa) at the tissue interface to reduce mechanical mismatch and the subsequent force-mediated activation of TGF-β1 and myofibroblasts [12].

- Advanced Encapsulation: Developing 3D barrier coatings, such as Atomic Layer Infiltration (ALI), to protect vulnerable parts of flexible microelectrodes from moisture and ion permeation, thereby delaying device failure [14].

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing and Mitigating Failure Modes

Problem 1: Gradual Degradation of Neural Recording Signal Quality

| Observation | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Solution & Prevention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decreasing signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) over weeks/months. | Fibrotic capsule formation increasing distance between electrodes and neurons [10]. | Histology: Explain tissue to quantify capsule thickness (e.g., Masson's Trichrome stain for collagen). Impedance Spectroscopy: Monitor increases in electrode impedance at low frequencies [9]. | Utilize softer, flexible materials (e.g., polyimide) to minimize mechanical mismatch [10]. Implement adhesive anti-fibrotic interfaces [8]. |

| Complete loss of signal from specific channels. | Individual electrode or interconnect failure due to moisture-induced corrosion [14]. | Leakage Current Testing: Measure under accelerated aging conditions (e.g., 87°C PBS). Visual Inspection: Use microscopy to identify delamination or cracks in encapsulation [14]. | Employ robust sidewall encapsulation strategies like 3D-Atomic Layer Infiltration (3D-ALI) to protect vulnerable areas [14]. |

Problem 2: Rising Impedance and Loss of Stimulation Efficacy

| Observation | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Solution & Prevention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Higher voltages required to achieve same therapeutic effect. | Fibrous capsule acting as an insulating layer [9] [8]. | Voltage Transient Measurement: Analyze changes in voltage waveforms during stimulation. Cyclic Voltammetry: Assess charge injection capacity of electrodes [9]. | Apply anti-fibrotic coatings (e.g., drug-eluting with TGF-β inhibitors) [12]. Design devices with smaller footprints and softer mechanics to reduce immune response [10]. |

| Inconsistent stimulation output. | Corrosion or delamination of stimulating electrode or leads [9]. | Continuous Impedance Monitoring: Track changes over time. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): Characterize the electrode-tissue interface [14]. | Select stable electrode materials like PtIr or IrOx. Ensure hermetic packaging and feedthroughs for the pulse generator [9]. |

Problem 3: Physical Device Failure or Damage

| Observation | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Solution & Prevention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broken lead wires or interconnects. | Mechanical fatigue from repetitive stress or strain due to body movement [9]. | Micro-CT Scan: Non-destructively inspect for fractures. Failure Analysis: Use SEM/EDS on explanted devices to examine fracture surfaces [9]. | Use stretchable or flexible conductive composites. Design strain-relief features in lead routing. Utilize elastic substrates like silicone [6]. |

| Delamination of thin-film layers. | Poor adhesion between dissimilar materials in a humid environment [14]. | Accelerated Aging Tests: Submerge in saline at elevated temperatures and monitor performance. Interface Toughness Measurement: Use standardized mechanical tests like peel tests [14]. | Implement gradient modulus interfaces like Atomic Layer Infiltration (ALI) to improve adhesion and resist delamination [14]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol 1: Quantifying Fibrotic Capsule Thickness

Objective: To histologically measure the extent of collagenous encapsulation around an explanted device.

Materials:

- Explanted device with surrounding tissue

- 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin

- Paraffin embedding station and microtome

- Masson's Trichrome stain kit

Methodology:

- Fixation: Fix explanted tissue-device construct in formalin for 48 hours.

- Processing & Sectioning: Process tissue through a graded ethanol series, embed in paraffin, and section at 5-10 µm thickness.

- Staining: Perform Masson's Trichrome staining following kit protocol. This stains collagen blue, cytoplasm red, and nuclei dark brown/black.

- Imaging & Analysis: Image sections under a light microscope. Use image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ) to measure the thickness of the blue collagenous capsule at multiple, random locations around the implant interface. Calculate average and standard deviation [8].

Protocol 2: Accelerated Aging Test for Device Encapsulation

Objective: To rapidly assess the long-term reliability of a device's moisture barrier in vitro.

Materials:

- Device Under Test (DUT)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Laboratory oven capable of maintaining 87°C

- Electrochemical impedance spectrometer or high-resistance meter

Methodology:

- Baseline Measurement: Record the initial electrical characteristics (e.g., impedance or leakage current) of the DUT.

- Submersion: Submerge multiple DUTs in PBS solution within sealed containers.

- Accelerated Aging: Place containers in an oven at 87°C. This elevated temperature accelerates failure mechanisms, simulating months of implantation in a matter of weeks.

- Monitoring: Periodically remove DUTs, rinse with DI water, dry, and re-measure electrical characteristics. Plot parameters like impedance magnitude versus aging time to identify failure points [14].

Key Signaling Pathways in Fibrosis

This diagram illustrates the core signaling pathways involved in the foreign body response and fibrotic encapsulation, highlighting the critical role of mechanical forces.

Fibrosis Signaling Pathway

Experimental Workflow for Implant Evaluation

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive workflow for evaluating the performance and failure modes of a bioelectronic implant, from in vitro testing to in vivo validation and post-analysis.

Implant Evaluation Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and reagents used in the development and testing of advanced bioelectronic implants, as featured in recent research.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Benefit | Key Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(vinyl alcohol)-based Adhesive | Forms a conformal, anti-fibrotic interface that prevents inflammatory cell infiltration and collagen deposition [8]. | Provides stable, long-term adhesion to wet tissues. Compared to commercial adhesives (Coseal, Tisseel), it shows superior prevention of fibrous capsule formation over 12 weeks [8]. |

| Soft Silicone (∼2 kPa) | Surface-modifying layer that reduces mechanical mismatch with soft tissue (∼1 kPa), minimizing pro-fibrotic TGF-β1 activation [12]. | Can be coated onto conventionally stiff silicones (~2 MPa) to significantly reduce collagen deposition and myofibroblast activation without affecting macrophage counts [12]. |

| Atomic Layer Infiltration (ALI) | Creates a gradient modulus hybrid material at the polymer-ceramic interface, resisting delamination and improving encapsulation reliability [14]. | Modifies standard ALD parameters to allow precursors to infiltrate the porous polymer matrix. Key for 3D sidewall encapsulation of freestanding microelectrodes [14]. |

| CWHM-12 Small Molecule Inhibitor | Antagonizes αv integrin binding to the LAP complex, suppressing the mechanical activation of TGF-β1 [12]. | A pharmacological strategy to prevent fibrosis around stiff implants when material softening is not feasible. Effective in murine subcutaneous implant models [12]. |

| In Silico FBR Model | A computational tool using standardized ODEs to predict fibrotic outcomes based on implant properties (stiffness, immunogenicity) [11]. | Bridges in vitro and in vivo studies. Useful for screening implant designs and materials in early R&D, potentially reducing animal testing. Validated against experimental anti-fibrotic interventions [11]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the "Mechanical Mismatch Problem" in bioelectronic implants? The mechanical mismatch problem refers to the detrimental effects caused by the significant difference in stiffness between traditional, rigid implant materials (like silicon and metals) and the soft, dynamic tissue of the brain. This stiffness discrepancy leads to continuous micromotion at the tissue-implant interface, which can provoke chronic neuroinflammation, scar tissue formation (gliosis), and instability of the blood-brain barrier, ultimately compromising the long-term performance and reliability of the device [15] [16].

Q2: What are the primary biological consequences of this mismatch? The primary consequences are a sustained neuroinflammatory response and instability of the blood-brain barrier. Research shows that stiff implants trigger a significant increase in the presence of activated immune cells (like microglia and astrocytes) around the implant site. Furthermore, the constant mechanical agitation can disrupt the delicate endothelial cells that form the blood-brain barrier, leading to increased permeability and potential further damage to neural tissue [15].

Q3: Are there innovative material strategies to overcome this problem? Yes, two prominent advanced strategies are:

- Mechanically-Adaptive Materials: These materials are rigid during surgical implantation for ease of handling but become soft and compliant after being exposed to the physiological conditions of the body, thereby minimizing the mechanical mismatch [15].

- Ultra-Soft & Flexible Bioelectronics: This approach involves using inherently soft, flexible, and stretchable materials from the outset. Recent developments include subcellular-sized, wireless electronic devices that can be non-surgically delivered, often integrated with living cells to create compliant hybrids that seamlessly interface with neural tissue [7] [16] [17].

Q4: How can I quantitatively evaluate the success of a compliant implant in my experiment? Success is evaluated through a combination of quantitative histological analysis and functional testing. Key metrics include quantifying the density of immune cells (e.g., microglia and astrocytes) at the implant interface, assessing blood-brain barrier integrity, and measuring the electrical impedance of the implant-tissue interface over time. Compliant implants should show a statistically significant reduction in these inflammatory markers and more stable electrical properties compared to stiff controls [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Chronic Neuroinflammatory Response Observed Around Implant

Potential Cause: The mechanical stiffness (Young's modulus) of your implant is too high compared to the surrounding brain tissue, causing persistent micromotion and tissue strain.

Solutions:

- Action 1: Switch to a compliant material system. Consider using mechanically-adaptive polymers or soft elastomers that closely match the brain's modulus (in the kilopascal range).

- Action 2: Implement a flexible form factor. Design implants with ultra-thin and porous geometries that can bend and flex with the brain tissue.

- Action 3: Validate with long-term studies. Ensure that your material remains compliant and stable over the entire planned duration of your experiment, as some materials may degrade or stiffen.

Problem: Unstable Electrical Recordings or Stimulation Efficacy Over Time

Potential Cause: The inflammatory response and subsequent formation of an insulating glial scar around a rigid implant increases the distance between the electrode and viable neurons, raising impedance and reducing signal quality.

Solutions:

- Action 1: Characterize the interface impedance. Regularly measure electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) to monitor the health of the electrode-tissue interface.

- Action 2: Prioritize biocompatibility and compliance. Use materials that minimize the foreign body response. Softer implants have been shown to develop a much thinner and less dense glial scar, preserving signal fidelity [15] [16].

- Action 3: Consider a non-surgical approach. For specific applications, novel methods like "Circulatronics"—where cell-borne electronic devices are injected and travel to the target site—can eliminate surgical trauma and the associated inflammatory cascade entirely [7] [17].

Key Experimental Data & Protocols

The table below summarizes key experimental data demonstrating the impact of implant stiffness on biological responses.

Table 1: Comparative Effects of Stiff vs. Compliant Intracortical Implants

| Parameter | Stiff Implants | Compliant Implants | Significance & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroinflammatory Response (Chronic) | Significantly Increased [15] | Significantly Reduced [15] | Measured at 2, 8, and 16 weeks post-implantation. |

| Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) Stability | Unstable [15] | More Stable [15] | Critical for preventing further neural damage. |

| Tissue Strain & Micromotion | High [16] | Low [16] | Driven by mechanical mismatch with soft brain tissue. |

| Typical Material Stiffness | GPa range (e.g., Silicon) [16] | kPa-MPa range (e.g., adaptive polymers) [15] [16] | Brain tissue stiffness is in the kPa range. |

| Long-term Recording/Stimulation Stability | Often Degrades [16] | Improved [15] [16] | Linked to reduced glial scarring. |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating the Neuroinflammatory Response to Implants

Objective: To quantitatively assess the chronic neuroinflammatory response to an intracortical implant with different mechanical properties.

Materials:

- Test implants (stiff control vs. compliant material).

- Animal model (e.g., rat cortex).

- Perfusion and fixation equipment.

- Primary antibodies: Anti-Iba1 (for microglia), Anti-GFAP (for astrocytes).

- Fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies.

- Confocal microscope.

Method:

- Implantation: Surgically implant the stiff and compliant devices into the target brain region (e.g., rat cortex) following sterile procedures and approved animal protocols.

- Survival Time: Allow animals to survive for the desired chronic time points (e.g., 2 weeks, 8 weeks, 16 weeks) to observe long-term tissue responses [15].

- Perfusion and Tissue Sectioning: At the endpoint, transcardially perfuse the animals with paraformaldehyde. Extract the brains, post-fix, and section them into coronal slices containing the implant site.

- Immunohistochemistry: Label the tissue sections using standard IHC protocols. Incubate slices with primary antibodies (Iba1, GFAP) overnight, followed by appropriate secondary antibodies.

- Imaging and Quantification: Capture high-resolution images of the tissue surrounding the implant using a confocal microscope. Quantify the inflammatory response by measuring:

- The density of Iba1-positive microglia within a defined radius (e.g., 100 µm) from the implant interface.

- The intensity and extent of GFAP-positive astrocytic scarring.

- Statistical Analysis: Perform statistical tests (e.g., t-test, ANOVA) to compare the quantified metrics between the stiff and compliant implant groups. A successful compliant implant will show a statistically significant reduction in both microglial activation and astrocytic scarring.

The Inflammatory Cascade Caused by Mechanical Mismatch

The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathway and biological sequence of events triggered by a rigid implant.

Mechanism of Implant-Induced Inflammation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Investigating Compliant Neural Implants

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanically-Adaptive Polymers | Initially rigid for implantation, become compliant in vivo to reduce mismatch [15]. | Verify the activation time and final modulus match your experimental needs. |

| Soft Elastomers (e.g., PDMS) | Model compliant materials with tunable Young's modulus for in vitro and in vivo testing. | Biocompatibility grades and surface modifications are crucial for integration. |

| Recombinant Human Collagen (rhCol) | Bioactive coating to enhance cell adhesion and integration on synthetic polymer scaffolds [18]. | Xeno-free and avoids immune reactions associated with animal-derived collagen. |

| Primary Antibodies (Iba1, GFAP) | Key immunohistochemical markers for quantifying microglial and astrocytic response. | Optimize dilution and staining protocols for your specific tissue model. |

| Subcellular-Sized Wireless Electronic Devices (SWEDs) | Enable non-surgical implantation and ultra-focal neuromodulation, bypassing surgical trauma [17]. | Requires development of cell-hybrid systems for targeting and wireless powering. |

| NS2 (114-121), Influenza | NS2 (114-121), Influenza, MF:C48H74N12O12, MW:1011.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Fmoc-Ser(PO(NHPr)2)-OH | Fmoc-Ser(PO(NHPr)2)-OH, MF:C24H32N3O6P, MW:489.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary biological challenges causing bioelectronic implant failure? The primary challenges are biofouling, the Foreign Body Response (FBR), and microbial colonization. Biofouling is the spontaneous accumulation of proteins, cells, and bacteria on the implant surface [19]. This triggers the FBR, a complex immune response that often results in the formation of a fibrous capsule, isolating the device and leading to failure [20] [19]. Microbial colonization can lead to biofilm formation, where communities of bacteria become highly resistant to antibiotics and the host immune system, causing persistent infections [21].

Q2: Why are biofilms on medical devices particularly problematic? Bacteria in a biofilm state can be 500 to 5,000 times more resistant to antibiotics than their free-floating counterparts [21]. The biofilm matrix acts as a physical barrier that prevents antibiotics from reaching the bacterial cells and facilitates the exchange of antimicrobial-resistant genes [21]. This leads to recalcitrant, chronic infections that are very difficult to eradicate without removing the device.

Q3: How does the surface property of an implant influence biofilm formation? The chemical composition and physical morphology of an implant's surface play a crucial role in bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation [21]. A conditioning film of host proteins and other organic molecules forms almost immediately on the implant after placement, which bacteria use as a nutrient source for initial attachment and growth [21].

Q4: What is the difference between reliability and stability in bioelectronic implants?

- Reliability is the probability that a device will function as intended without failure over a specified period. It is measured by metrics like mean time between failures (MTBF) [16] [6].

- Stability refers to the device's ability to maintain its functional and structural properties over time, with minimal drift in performance, despite environmental and biological fluctuations [16] [6].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Problem 1: Rapid Signal Degradation in Chronic Animal Studies

Potential Cause: Fibrous encapsulation of the implant due to the Foreign Body Response (FBR), blocking analyte diffusion or altering electrical properties [19]. Solutions:

- Consider Soft Materials: Shift from rigid (silicon, metal) to soft, flexible materials (polymers, elastomers) that better match tissue mechanics and reduce inflammatory response [16] [6].

- Apply Anti-fouling Coatings: Use coatings such as zwitterionic polymers, polyethylene glycol (PEG), or biomimetic slippery liquid-infused porous surfaces (SLIPS) to prevent protein and cell adhesion [19] [22] [23].

Problem 2: Bacterial Contamination and Biofilm Formation on Explanted Devices

Potential Cause: Ineffective anti-biofouling strategy or surface defects that act as nucleation sites for bacterial attachment [21] [22]. Solutions:

- Implement Nature-Inspired Coatings: Develop surfaces with nanoscale topographies inspired by cicada wings (bactericidal) or shark skin (anti-adhesive) to physically prevent colonization [23].

- Use Biocidal Release Coatings: Incorporate and test coatings that elute antibiotics or silver ions; however, be aware of finite reservoir life and potential for antibiotic resistance [21] [19].

Problem 3: Inconsistent In Vitro to In Vivo Translation of Anti-fouling Strategies

Potential Cause: Static in vitro tests may not replicate the dynamic, complex immune and microbial environment in a living organism [21] [19]. Solutions:

- Refine In Vitro Models: Incorporate dynamic flow conditions and complex protein solutions to better simulate the in vivo environment [21].

- Conduct Early Pilot In Vivo Studies: Perform short-term animal studies to quickly assess the host response and coating stability before committing to long-term chronic studies [22].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Evaluating Anti-biofouling Coatings Using an In Vitro Bacterial Adhesion Assay

Objective: To quantitatively compare the ability of different surface modifications to resist bacterial colonization. Materials:

- Coated and uncoated implant material samples.

- Bacterial culture (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus or S. epidermidis).

- Standard growth broth and agar plates.

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS).

- Fluorescence microscope and DNA-binding stain (e.g., SYTO 9).

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Sterilize all test samples (e.g., via UV irradiation or ethanol wash).

- Bacterial Inoculation: Immerse samples in a bacterial suspension of a standardized concentration (e.g., 10^7 CFU/mL) and incubate under gentle agitation for a set period (e.g., 2-24 hours).

- Rinsing: Gently rinse samples with PBS to remove non-adhered planktonic bacteria.

- Fixation and Staining: Fix adhered bacteria and stain with a fluorescent DNA dye.

- Quantification: Image multiple fields of view per sample using fluorescence microscopy and use image analysis software to count the number of adhered bacteria per unit area. Alternatively, detach bacteria by sonication and perform serial dilution plating to determine Colony Forming Units (CFU).

Protocol 2: Assessing the Foreign Body Response (FBR) and Biofilm Formation In Vivo

Objective: To evaluate the long-term biocompatibility and infection resistance of an implant coating in a rodent model. Materials:

- Test and control implant materials.

- Animal model (e.g., mouse or rat).

- Surgical equipment and anesthetic.

- Histology reagents: formalin, paraffin, Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) stain, Masson's Trichrome stain.

- Equipment for bacterial quantification: homogenizer, agar plates.

Methodology:

- Implantation: Surgically implant material samples subcutaneously or at the relevant anatomical site under aseptic conditions. For infection challenge models, introduce a known quantity of bacteria at the time of implantation.

- Explanation: After a predetermined period (e.g., 1, 4, or 12 weeks), euthanize the animals and explant the devices with surrounding tissue.

- Analysis:

- Microbial Load: Homogenize the explanted device and a portion of the surrounding tissue. Plate the homogenate on agar to quantify viable bacteria (CFU).

- Histological Analysis: Fix the tissue in formalin, embed in paraffin, section, and stain.

- H&E Staining: Assess general tissue architecture and inflammatory cell infiltration.

- Masson's Trichrome Staining: Visualize collagen deposition and quantify the thickness of the fibrous capsule forming around the implant.

Table 1: Comparison of Advanced Anti-Biofouling and Anti-Biofilm Surface Strategies

| Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Key Advantages | Potential Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SLIPS (Slippery Liquid-Infused Porous Surfaces) [22] | Creates a dynamic, immobilized liquid interface that prevents bacterial adhesion and is self-healing. | Broad-spectrum anti-adhesion; protects against a wide range of contaminants and bacteria. | Long-term stability of the lubricant layer in vivo; requires a compatible porous substrate. |

| Biomimetic Nanotopographies [23] | Physically ruptures bacterial membranes using nanoscale sharp features inspired by insect wings. | Non-chemical, avoids antibiotic resistance; long-lasting physical effect. | Complex fabrication; potential for clogging or damage to nanostructures. |

| Zwitterionic & Hydrophilic Polymer Brushes [19] [23] | Forms a hydration layer via strong electrostatic interactions, creating a physical and energetic barrier to protein adsorption. | Highly effective against non-specific protein fouling; can be chemically tuned. | Long-term stability and susceptibility to oxidative degradation in vivo. |

| Controlled Biocidal Release [21] [19] | Locally elutes antibiotics or antimicrobial agents (e.g., silver ions) to kill approaching bacteria. | Highly effective in the short term. | Finite reservoir leads to limited functional lifetime; promotes antimicrobial resistance. |

| Electroceutical Therapy [24] | Uses programmable electrical stimulation to disrupt bacterial communication (quorum sensing) and prevent biofilm formation. | Drug-free approach; can be tailored and activated on demand. | Emerging technology; long-term effects and optimal parameters still under investigation. |

Table 2: Quantitative Results from Key Anti-Biofouling Studies

| Study & Strategy | Experimental Model | Key Quantitative Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| SLIPS-coated ePTFE | In vivo rodent model challenged with S. aureus | ~85% reduction in bacterial colonization on explanted devices compared to controls. | [22] |

| Electroceutical Patch | Preclinical test on pig skin | Achieved nearly a tenfold (10x) reduction in bacterial colonization. | [24] |

| Computational Model of Biocide-Releasing Surface | In silico simulation of marine biofilm formation | Predicted that the time to biofilm establishment depends exponentially on the surface biocide concentration and the arrival rate of resistant organisms. | [25] |

Visualization of Key Concepts

Biofilm Development Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Investigating the Tissue-Device Interface

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Zwitterionic Polymers | Create highly hydrophilic, anti-fouling surfaces that resist non-specific protein adsorption [19]. | e.g., Poly(sulfobetaine methacrylate) (PSBMA). Used as a coating to minimize the initial conditioning film. |

| Fluorinated Lubricants | Key component for creating SLIPS coatings; provides the dynamic, anti-adhesive liquid layer [22]. | e.g., Perfluoropolyether (PFPE), Perfluoroperhydrophenanthrene (PFPH). Must have high chemical affinity for the substrate. |

| Catechol-Based Polymers | Provide strong, versatile adhesion to various substrates in wet environments, inspired by mussel adhesives [23]. | e.g., Polydopamine. Often used as a primer layer for subsequent functionalization with biomolecules or other polymers. |

| RGD Peptide Sequences | Promote specific cell adhesion and tissue integration by mimicking the extracellular matrix (ECM) [23]. | Coated on implants to improve biocompatibility and reduce the FBR by encouraging host tissue acceptance. |

| Fluorescent DNA Stains | Enable visualization and quantification of adhered bacteria and biofilms on explanted devices or in vitro samples. | e.g., SYTO 9 (for live cells). Critical for confocal microscopy analysis of biofilm structure and biomass. |

| Triamcinolone acetonide-d7-1 | Triamcinolone acetonide-d7-1, MF:C24H31FO6, MW:441.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| N-Octanoyl-D15-glycine | N-Octanoyl-D15-glycine, MF:C10H19NO3, MW:216.35 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Engineering Solutions: Material Innovations and Design Strategies for Bio-integrative Implants

Core Concepts: Why Soft Bioelectronics?

FAQ: Why is the mechanical mismatch between implants and tissue a significant problem?

Traditional bioelectronics are fabricated from rigid materials like metals and silicon. When implanted into soft, dynamic biological tissues, this stiffness difference creates a mechanical mismatch. The body recognizes this rigid interface as a foreign body, initiating a chronic immune response. This typically results in the formation of a fibrotic scar tissue capsule that walls off the device. This encapsulation electrically insulates the implant, severely degrading signal quality and often leading to device failure over time [6] [26].

FAQ: How do soft and flexible materials mitigate the immune response?

Soft bioelectronics, made from polymers, elastomers, and hydrogels, have a Young's modulus much closer to that of natural tissue (typically in the kPa to MPa range). This mechanical compatibility minimizes chronic irritation and micromotion damage as the body moves. Consequently, the foreign body response is significantly reduced, leading to better tissue integration, less fibrotic encapsulation, and more stable long-term performance [6] [16].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Rigid vs. Soft Bioelectronics

| Property | Rigid Bioelectronics | Soft & Flexible Bioelectronics |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Material Types | Silicon, metals, ceramics | Polymers, elastomers, hydrogels, thin-film materials [6] |

| Young's Modulus | > 1 GPa | 1 kPa – 1 MPa [6] |

| Bending Stiffness | > 10â»â¶ N·m | < 10â»â¹ N·m [6] |

| Tissue Integration | Poor; stiffness mismatch causes inflammation and fibrotic encapsulation | Excellent; soft, conformal materials match tissue mechanics and reduce immune response [6] |

| Signal Fidelity | Strong short-term signal quality, but long-term degradation due to scar tissue | Better chronic signal stability due to stable tissue-contact interface [6] |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ: My soft device is delaminating in aqueous biological environments. What are potential solutions?

Delamination is a common failure mode for multilayer soft devices due to water permeation and weak interfacial adhesion.

- Solution A (Encapsulation): Implement advanced encapsulation strategies using ultrathin, flexible barrier layers (e.g., parylene, silicon carbide, or novel polymers) that protect internal components while maintaining overall device flexibility [6] [27].

- Solution B (Material Innovation): Shift towards monolithic devices or use materials with inherent adhesion. For example, conductive hydrogels can be designed to have interpenetrating polymer networks that create a more unified structure, significantly reducing delamination risk [26].

FAQ: I am observing a decline in the conductivity of my flexible conductive traces under repeated strain. How can I address this?

Conductive materials on soft substrates can suffer from microcracking and fatigue.

- Solution A (Geometric Engineering): Use serpentine or fractal "kirigami/origami" designs for metal traces. These geometries allow the material to stretch and bend without subjecting the conductive metal to excessive tensile strain, thus preventing crack formation [6].

- Solution B (Alternative Conductors): Replace traditional metal films with conductive composites or liquid metals. PEDOT:PSS-based conductive hydrogels or gallium-indium alloys maintain conductivity even under deformation and are a focus of current research [26].

FAQ: My in vivo experiment shows unexpected inflammation despite using a soft substrate. What could be the cause?

While softness reduces the primary mechanical trigger for inflammation, other factors can be at play.

- Diagnostic Steps:

- Check Edge Sharpness: Even a soft device can have microscopically sharp edges that aggravate local tissue.

- Verify Material Purity: Ensure no leachable toxic compounds (e.g., residual solvents or unreacted monomers) are present in your polymer or hydrogel.

- Assess Device Size and Tethering: A very large device or one that is tightly tethered can still cause macro-motion irritation, provoking a response [9].

Experimental Protocols & Characterization

Standardized Protocol for In Vivo Biocompatibility and Stability Assessment

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the chronic immune response and functional stability of a novel soft bioelectronic implant.

- Implantation: Aseptically implant the device in the target tissue (e.g., subcutaneous, neural) of an animal model. Ensure surgical controls are identical.

- Chronic Monitoring:

- Functional Electrochemistry: Perform electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and cyclic voltammetry (CV) weekly at the electrode-tissue interface. A stable or slowly increasing impedance indicates minimal fibrotic growth.

- Biological Sampling: Collect blood serum at predefined intervals (e.g., 1, 4, and 12 weeks) to quantify systemic inflammatory biomarkers (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) via ELISA.

- Endpoint Analysis:

- Histology: Explain the device and surrounding tissue. Process for H&E staining and immunohistochemistry for specific cell markers (e.g., CD68 for macrophages, α-SMA for fibroblasts).

- Fibrosis Quantification: Measure the thickness of the collagen-rich fibrotic capsule (stained with Masson's Trichrome or Picrosirius Red) using image analysis software. A thinner capsule signifies a superior biocompatible response [9].

Workflow Diagram: From Problem to Solution in Bioelectronics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Materials for Developing Soft Bioelectronic Implants

| Material/Reagent | Function | Key Characteristics & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Conductive Hydrogels (e.g., PEDOT:PSS-based) | Serves as the soft, conductive interface for stimulation/recording. Mimics tissue modulus and supports electronic properties [26]. | Nontoxic additives can be used to dope and enhance performance. Key for fabricating soft microelectronics. |

| Elastomeric Substrates (e.g., PDMS, SEBS) | Provides the flexible and stretchable structural backbone for the device. | Offers low Young's modulus and high stretchability, allowing devices to conform to dynamic tissues. |

| Electrospun Polymer Nanofibers | Creates porous, high-surface-area scaffolds for sensing or tissue integration. | Enables convenient microstructure generation and improved functionalization at low cost [28]. |

| Flexible Encapsulants (e.g., Parylene, Silicone) | Forms a barrier to protect electronic components from ionic body fluid ingress. | Must be thin, flexible, and possess low water vapor transmission rates to ensure long-term stability [6] [27]. |

| Soft Adhesives (e.g., Bio-adhesive Hydrogels) | Allows the device to securely attach to wet, moving tissue surfaces without sutures. | Provides strong, biocomhesive interface while maintaining softness and compliance. |

| 2-Methylthio-AMP diTEA | 2-Methylthio-AMP diTEA, MF:C23H46N7O7PS, MW:595.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Curcumin monoglucuronide | Curcumin monoglucuronide, MF:C27H28O12, MW:544.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support resource addresses common experimental challenges in developing bioelectronic implants, with a focus on mitigating inflammation through advanced material science.

Conducting Polymers (CPs)

Q1: My PEDOT:PSS film has low conductivity and poor adhesion to the flexible substrate. What can I do?

- Problem: A common issue is the inability to balance high electrical performance with robust mechanical integration.

- Solution: Implement a solvent-mediated solid-liquid interface (SLI) doping strategy to engineer a vertically phase-separated (VPS) structure.

- Protocol:

- Blade Coating: Apply commercial PEDOT:PSS ink onto your substrate to form a pre-oriented pristine film.

- SLI Doping: Shear a metastable liquid-liquid contact (MLLC) doping dispersion (an ethylene glycol-diluted PEDOT:PSS formulation with a reduced PSS/PEDOT ratio) onto the surface of the pristine film.

- Annealing: Anneal the film. This process encourages PSS (hydrophilic) to migrate to the surface, improving adhesion to biological tissues, while PEDOT-rich domains aggregate at the bottom, enhancing crystallinity and conductivity. This VPS structure can achieve conductivities up to ~8800 S cmâ»Â¹ [29].

- Prevention: Precisely control coating speed and solvent evaporation during the SLI process to optimize polymer alignment and phase separation.

Q2: How can I improve the chronic stability of my neural electrode coated with a conductive polymer?

- Problem: The charge-transfer efficiency of the electrode degrades over time, often due to fibrotic encapsulation (gliosis) and mechanical mismatch.

- Solution: Use softer, electrodeposited CP composites that mimic tissue mechanics and can be biofunctionalized.

- Protocol (for Electrodeposited PEDOT/HAp Coatings):

- Solution Preparation: Prepare an aqueous solution containing 0.1 M EDOT monomer and a bioactive dopant, such as 0.5% (w/v) hyaluronic acid (HAp).

- Electrodeposition: Use a standard three-electrode system. Apply a constant current density (e.g., 0.5 mA/cm²) for 100-200 seconds to deposit the PEDOT/HAp film directly onto your metal electrode (working electrode) [30] [31].

- Characterization: Use cyclic voltammetry and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy to verify a lower impedance and higher charge storage capacity compared to bare metal electrodes.

- Rationale: CPs like PEDOT facilitate efficient ionic-electronic charge transfer. Incorporating a bioactive dopant like HAp can improve biocompatibility, reduce the foreign body response, and enhance integration [31].

Hydrogels and Conductive Hydrogels (CHs)

Q3: My conductive hydrogel is too mechanically weak for handling or implantation.

- Problem: Achieving high electrical conductivity often compromises mechanical robustness and processability.

- Solution: Form a dual-network hydrogel with tunable mechanical properties.

- Protocol (for PVA/Gelatin Dual-Network Hydrogel):

- Preparation: Dissolve Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) in a binary solvent of glycerol and water. Add gelatin to the mixture.

- Gelation: Inject the solution into a mold and freeze at -20°C for several hours. Subsequently, thaw at 25°C for 2 hours. Repeat this freeze-thaw cycle to form a stable microcrystalline PVA network.

- Tuning: Adjust the glycerol content (e.g., a 40% ratio was found optimal in one study) to balance elasticity and flexibility. The glycerol forms strong hydrogen bonds with PVA, increasing tensile strength [32].

- Alternative: For conductive hydrogels, incorporate Fe³⺠ions as dynamic cross-linkers into a gelatin/poly(acrylic acid-co-acrylamide) network. The Fe³⺠concentration can tune both mechanical toughness (up to 569% elongation at break) and electrical conductivity [32].

Q4: How can I fabricate a microelectrode array on a soft hydrogel substrate?

- Problem: Standard microfabrication techniques are not compatible with soft, water-swollen hydrogels.

- Solution: Utilize laser processing to pattern high-fidelity circuits on conductive polymer films, which can be integrated with hydrogel systems.

- Protocol:

- Film Preparation: First, create a highly conductive and patternable film, such as the VPS PEDOT:PSS film described in Q1 [29].

- Laser Patterning: Use a laser ablation system to directly write and pattern the desired microelectrode array design onto the film.

- Integration: The laser-patterned film can serve as a conformable electrode layer in contact with or laminated to a softer hydrogel layer for final device assembly [29].

Bioresorbable Composites

Q5: The degradation rate of my bioresorbable nerve guide is too fast, losing mechanical strength before tissue healing is complete.

- Problem: Rapid degradation leads to premature loss of mechanical support and potential inflammatory responses.

- Solution: Use composite materials to finely tune the degradation profile and mechanical properties.

- Protocol (for β-Tricalcium Phosphate (β-TCP) Polymer Composite):

- Material Selection: Select a biodegradable polymer matrix (e.g., PLGA) and blend it with β-TCP ceramic particles.

- Fabrication: Fabricate the scaffold using methods like solvent casting, compression molding, or 3D printing, ensuring a homogeneous distribution of β-TCP.

- Rationale: β-TCP has a chemical composition similar to bone mineral, is osteoconductive, and degrades slower than some fast-resorbing polymers. Its incorporation buffers the local pH during polymer degradation, mitigating inflammatory reactions and providing a more controlled resorption timeline (typically from 10 months to 2 years in bone models) [33].

Q6: What are the key scaffold design factors to minimize inflammation in tissue engineering?

- Problem: Scaffold design triggers a foreign body response, leading to fibrotic encapsulation and implant failure.

- Solution: Optimize scaffold characteristics to promote integration and minimize mechanical mismatch.

- Guidelines:

- Porosity: Ensure a minimum pore size of 100 µm for nutrient diffusion, with ideal pore sizes of 200-350 µm for bone tissue in-growth [33].

- Mechanical Properties: Tailor the elastic modulus to match the target tissue (1 kPa - 1 MPa for soft tissues) to reduce shear stress and chronic inflammation [34].

- Surface Chemistry: Use bioactive materials (e.g., HAp, specific peptides) that support normal cellular activity and osteoconduction [33].

Experimental Data and Material Properties

Table 1: Key Properties of Conducting Polymers for Neural Interfaces

| Polymer | Typical Conductivity Range | Key Advantages | Reported High Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS | 1 - 10â´ S cmâ»Â¹ [29] | Tunable conductivity, commercial availability, biocompatibility. | ~8800 S cmâ»Â¹ with VPS structure [29]. |

| Polypyrrole (PPy) | Widely investigated [31] | Excellent aqueous processability, good cytocompatibility. | Often used with bioactive dopants (e.g., laminin) for neural growth [31]. |

| Poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT) | Used in photovoltaics [17] | Organic semiconductor, tunable for specific optical wavelengths. | VOC = 0.2 V, ISC = 12.8 nA (10 µm device at 10 mW mmâ»Â²) [17]. |

Table 2: Mechanical and Electrical Properties of Hydrogel-Based Materials

| Material Type | Elastic Modulus | Stretchability | Electrical Conductivity | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Tissues | 1 Pa - 100 kPa [32] | High | Ionic | Target for mechanical matching. |

| Conventional Electronics | 10 - 200 GPa [32] | < 1% (brittle) | High (electronic) | Source of mechanical mismatch. |

| Hydrogels | 1 kPa - 1 MPa [34] | ~20-75% [34] | N/A (Insulating) | Biocompatible, tissue-like scaffold. |

| Conductive Hydrogels (CHs) | < 100 kPa [34] | > 100% strain [34] | 10â»â´ - 10² S/m [34] | Enable ionic-electronic charge transfer at the interface. |

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS | Intrinsically conductive polymer. | Core material for neural electrodes and wearable sensors [29] [31]. |

| Poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT) | Organic semiconducting polymer (donor material). | Active layer in subcellular-sized, wireless photovoltaic devices for neuromodulation [17]. |

| β-Tricalcium Phosphate (β-TCP) | Bioresorbable, osteoconductive ceramic. | Composite filler in bone grafts to control degradation and support remodeling [33]. |

| Hyaluronic Acid (HAp) | Bioactive glycosaminoglycan and dopant. | Incorporated into PEDOT as a dopant to improve biocompatibility and reduce inflammation [31]. |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | Hydrogel-forming polymer. | Base for dual-network hydrogels to create tough, tunable mechanical substrates [32]. |

| Fe³⺠Ions | Dynamic cross-linker and conductive additive. | Used to tune the mechanical toughness and electrical conductivity of gelatin-based hydrogels [32]. |

Experimental Workflow Visualizations

Conductive Polymer Electrode Fabrication

Hydrogel-Based Implant Development

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

FAQ 1: How can I improve the long-term stability and signal fidelity of my neural implant?

Answer: The most common cause of signal degradation over time is the foreign body response (FBR), which leads to inflammation and glial scar formation. This is often triggered by a mechanical mismatch between the implant and the native tissue.

- Problem: Conventional rigid implants (made from silicon or metals) have a Young's modulus in the GPa range, while brain tissue is in the kPa range. This stiffness mismatch causes chronic inflammation and eventual signal loss [10] [35].

- Solution: Transition to soft, flexible materials that mechanically mimic neural tissue.

- Material Choices: Use polymers like polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), polyimide (PI), or parylene-C as substrates and encapsulants [35].

- Design Strategies: Implement ultra-thin films (<10 µm), mesh geometries, or serpentine structures to reduce flexural rigidity and improve conformability with tissue [35]. These designs minimize micromotion-induced damage and dampen the FBR, leading to more stable long-term recordings [35] [9].

FAQ 2: What are the key failure points I should monitor in a chronic implantation study?

Answer: Failures can be abiotic (technical/mechanical) or biotic (biological). A systematic checklist is provided below for key components [9].

Table: Chronic Implant Failure Mode Checklist

| Component | Common Failure Modes | Diagnostic & Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Electrodes | Corrosion, delamination, increased impedance [9]. | Use stable coatings (e.g., Iridium Oxide); perform regular electrochemical impedance spectroscopy [9]. |

| Lead Wires/Interconnects | Fatigue fracture from repeated movement [9]. | Use flexible polymers (e.g., silicone) for insulation; inspect with micro-CT scanning [9]. |

| Packaging | Loss of hermeticity, moisture ingress [9]. | Use robust housing (e.g., titanium); conduct accelerated aging tests [9]. |

| Tissue Interface | Glial scarring, neuronal loss, chronic inflammation [10] [35]. | Use soft materials; perform post-mortem histology for astrocytes (GFAP) and microglia (Iba1) markers [35]. |

FAQ 3: My goal is to achieve intracellular recording from a network of neurons. What high-density array technologies should I consider?

Answer: Recent advances in CMOS-based platforms now enable parallel intracellular recording and stimulation, bridging the gap between traditional patch-clamp and large-scale extracellular electrophysiology [10].

- Technology: CMOS-integrated circuits with vertical nanoelectrodes or microhole arrays.

- Key Specifications:

- Electrode Density: Platforms with 4,096 electrodes are available, capable of mapping over ~70,000 synaptic connections among thousands of neurons [10].

- Electrode Design: Nanoelectrodes (~2 µm diameter) or microholes (~2 µm diameter) allow neurons to seal over the electrodes, enabling stable recording of subthreshold membrane potentials [10].

- Material: Platinum-black (PtB) is often used to enhance surface area, reduce impedance, and increase charge injection capacity for stimulation [10].

FAQ 4: Are there non-surgical alternatives for deploying neural interfaces in deep brain regions?

Answer: Yes, an emerging paradigm called "Circulatronics" offers a non-surgical approach for deep brain neuromodulation [7] [17].

- Principle: Subcellular-sized, wireless electronic devices (SWEDs) are fused with living immune cells (e.g., monocytes) to create cell-electronics hybrids.

- Workflow: These hybrids are injected intravenously. The living cells camouflage the electronics, enabling them to cross the intact blood-brain barrier and autonomously traffic to sites of inflammation in the brain. Once there, they can be wirelessly powered to provide focal electrical stimulation [17].

- Key Advantage: This method eliminates the need for invasive intracranial surgery and its associated risks, providing a platform for highly precise neuromodulation [7].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication and In Vitro Validation of "Living Electrodes" (μTENNs)

This protocol details the creation of Microtissue Engineered Neural Networks (μTENNs) as a biological interface for optobiological monitoring and modulation [36].

1. Aim: To biofabricate implantable, optically controlled living electrodes that can synaptically integrate with host neural circuitry, providing a more specific and stable neural interface.

2. Materials

- Hydrogel: Agarose (3% w/v in DPBS)

- Cells: Primary cortical neurons isolated from embryonic day 18 rats

- Culture Media: Serum-free neuronal culture media (Neurobasal + B27 + Glutamax)

- Mold: Custom-designed acrylic mold and acupuncture needles for microcolumn fabrication

- Aggregation Device: PDMS wells with inverted pyramidal shapes

3. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Fabricate Agarose Microcolumns:

- Insert acupuncture needles into the custom acrylic mold channels.

- Pour molten agarose into the assembly and allow it to cool and solidify.

- Remove the needles and disassemble the mold to yield hollow agarose microcolumns (e.g., 398 µm OD, 180 µm ID). Cut to the desired length [36].

- Prepare Neuronal Aggregates:

- Dissociate cortical tissue and suspend neurons in culture media at 1.0-2.0 million cells/ml.

- Transfer the cell suspension to the pyramidal PDMS wells.

- Centrifuge at 200g for 5 min to force aggregate formation.

- Incubate overnight at 37°C, 5% CO2 [36].

- Seed Microcolumns to Create μTENNs:

- Remove microcolumns from DPBS and clear fluid from the channels.

- Pipette a single neuronal aggregate into one or both ends of the microcolumn to create unidirectional or bidirectional μTENNs, respectively.

- Culture the constructs, allowing axons to grow through the microcolumn, forming a long, protected axonal tract [36].

- Optogenetic Transduction & In Vitro Validation:

- Transduce μTENN neurons to express optogenetic proteins (e.g., Channelrhodopsin-2) before or during culture.

- Validate functionality using simultaneous optical stimulation and recording (e.g., calcium imaging or electrophysiology) to confirm network activity and control [36].

Diagram Title: Living Electrode (μTENN) Fabrication Workflow

Protocol 2: Establishing a "Circulatronics" System for Non-Surgical Brain Implantation

This protocol outlines the creation and in vivo application of cell-SWED hybrids for non-surgical, focal neuromodulation [17].

1. Aim: To develop and administer subcellular-sized wireless electronic devices (SWEDs) fused with immune cells that can autonomously implant in a target brain region after intravenous injection.

2. Materials

- SWEDs: Fabricated organic photovoltaic devices (e.g., ~10 µm diameter, ~200 nm thick).

- Cells: Primary monocytes (diameter 12-18 µm).

- Fabrication Substrate: Silicon wafer with sacrificial aluminum layer.

- Release Agent: Tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH).

- In Vivo Model: Mice with localized brain inflammation.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Fabricate and Release SWEDs:

- Mass-fabricate SWEDs on a 4-inch silicon wafer using CMOS-compatible processes. The structure is typically anode/organic semiconductor blend/cathode.

- Release the SWEDs from the substrate by etching the sacrificial aluminum layer with TMAH.

- Collect the free-floating SWEDs and confirm their power conversion efficiency remains functional [17].

- Create Cell-SWED Hybrids:

- Isolate primary monocytes.

- Use a covalent chemical reaction to fuse the SWEDs to the monocytes, creating stable hybrids. The living cells act as a biological camouflage and targeting system [17].

- Intravenous Administration and Implantation:

- Inject the cell-SWED hybrids intravenously into the animal model.

- The monocytes naturally traffic to sites of inflammation in the brain, carrying the SWEDs across the intact blood-brain barrier.

- The hybrids autonomously implant in the inflamed target region [17].

- Wireless Neuromodulation:

- Apply near-infrared (NIR) light transcranially to power the implanted SWEDs photovoltaically.

- The SWEDs convert optical energy to electrical potentials, enabling focal electrical stimulation of the surrounding neural tissue with high spatial precision (~30 µm) [17].

Diagram Title: Circulatronics Implantation and Stimulation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Novel Neural Interface Research

| Research Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Characteristics & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Soft Polymer Substrates (PDMS, Polyimide, Parylene-C) [35] | Insulating substrate and encapsulation for flexible neural probes. | Biocompatible, mechanically compliant (low Young's modulus), and processible with conventional lithography. Reduces FBR. |

| Conductive Polymers (PEDOT:PSS) [35] | Electrode coating or free-standing electrode material. | Enhances conductivity, reduces electrode impedance, and improves signal-to-noise ratio in recording and stimulation. |

| Agarose Hydrogel [36] | Scaffold for "Living Electrodes" (μTENNs). | Forms biocompatible microcolumns that protect and guide axonal growth in 3D engineered neural tissue. |

| Primary Cortical Neurons [36] | Cellular component for μTENN biofabrication. | Forms the functional, synaptically active core of the living electrode, enabling integration with host circuitry. |

| Primary Monocytes [17] | Cellular carrier for Circulatronics devices. | Naturally targets sites of inflammation, enabling blood-brain barrier crossing and precise self-implantation of SWEDs. |

| Organic Photovoltaic Polymers (e.g., P3HT, PCPDTBT) [17] | Active layer material for Subcellular-sized Wireless Electronic Devices (SWEDs). | Enables wireless powering via near-infrared light; biocompatible and tunable for different optical wavelengths. |

| Platinum-black (PtB) [10] | Coating for high-density microelectrodes. | High surface area reduces impedance and increases charge injection capacity, crucial for intracellular recording/stimulation. |

| GABAA receptor agent 6 | GABAA Receptor Agent 6 | GABAA receptor agent 6 is a high-purity chemical for neuroscientific research. This product is For Research Use Only and not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapy. |

| Ivabradine impurity 7-d6 | Ivabradine impurity 7-d6, MF:C27H34N2O6, MW:488.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

FAQs: Immune Response to Bioelectronic Implants

1. What are the primary immune challenges faced after bioelectronic implant insertion? The initial immune response to an implant begins with an acute inflammatory reaction to the injury and the innate recognition of the foreign material itself. This is characterized by protein deposition on the biomaterial, activation of complement proteins, and the recruitment of polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) and monocytes to the injury site [37]. These cells release reactive oxygen species (ROS) and pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β and TNF-α, which can cause secondary tissue damage and hinder device integration [37]. This can transition to a chronic phase involving lymphocytes, potentially leading to fibrosis (scar tissue formation) around the implant, which can isolate the device and compromise its long-term function [37].

2. How can surface engineering directly influence the immune response? Surface engineering aims to create biocompatible interfaces with properties designed to enhance the biological response and reduce polymicrobial accumulation, which can trigger inflammation [38]. This can be achieved by:

- Modifying Physicochemical Properties: Altering surface topography, chemistry, and energy to make the surface less recognizable as foreign, thereby dampening the foreign body reaction [37].

- Incorporating Active Agents: Developing antimicrobial or immunomodulatory coatings that utilize a range of compounds for contact-killing or as localized drug-delivery systems to manage the immune environment actively [38].

3. What surface topographies are known to promote a favorable (M2) macrophage phenotype? While specific topographies are not detailed in the provided search results, the principle is that the physical and mechanical properties of the implant surface are largely responsible for the foreign body reaction propagated by infiltrating immune cells [37]. Research in biomedical engineering focuses on creating specific surface architectures that can direct immune cell polarization toward the regenerative/anti-inflammatory (M2) macrophage phenotype, which is associated with tissue healing and repair, rather than the inflammatory (M1) phenotype [37].

4. My in vivo experiments show unexpected fibrosis. What surface properties should I re-evaluate? Unexpected fibrosis is a sign of a persistent chronic inflammatory response. You should systematically investigate the following surface properties:

- Surface Chemistry: Assess whether degradation products from your coating or base material are pro-inflammatory [37].

- Topography and Roughness: Re-evaluate the micro- and nano-scale features of your surface, as these directly influence how immune cells like macrophages and fibroblasts adhere and behave [37].

- Coating Stability: Verify the integrity and adhesion of any functional coatings under physiological conditions. Delamination or inconsistent coating can expose underlying materials, triggering a stronger immune reaction [39].

5. How do I accurately characterize the mechanical properties of a thin functional coating? Characterizing the mechanical properties of engineered surfaces at the appropriate length scale is key to understanding performance [39]. Key methods include:

- Nanoindentation: Used to measure hardness and elastic modulus, with advanced versions capable of operating at high temperatures to simulate demanding environments [39].

- Micro-Scratch Testing: Conducted with apparatus designed to measure coating durability and adhesion, often while observed in an electron microscope to understand failure mechanisms [39].

- Focused Ion Beam (FIB) Milling: Used to create micro-pillars or cantilevers from the coating, whose mechanical properties can then be measured under an electron microscope [39].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Persistent Inflammation and Fibrosis Around the Implant

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Potential Surface Engineering Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Pro-inflammatory surface chemistry | - Perform surface analysis (XPS, FTIR) to confirm coating composition. - Test in vitro for macrophage activation (M1 cytokine secretion: IL-1β, TNF-α) [37]. | Apply a bio-inert coating or a coating that releases anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-4, IL-10) to promote M2 macrophage polarization [37]. |

| Incorrect surface topography | - Use SEM to characterize surface topography at multiple scales. - Correlate specific topographical features with fibroblast activation in vitro. | Re-engineer the surface topography to feature structures known to discourage fibroblast proliferation and collagen deposition, promoting a more regenerative interface. |

| Unstable or degrading coating | - Use adhesion tests (e.g., tape test, scratch test) post-implantation [39]. - Analyze explanted surfaces for signs of delamination or wear. | Optimize the coating deposition method to improve adhesion and stability. Consider using functionally graded coatings (FGCs) for better integration and mechanical performance [40]. |

Issue 2: Poor Bio-Integration and Device Failure

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Potential Surface Engineering Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Robust foreign body reaction | - Histological analysis of the implant-tissue interface for presence of giant cells and a thick fibrous capsule [37]. | Modify surface energy and wettability to reduce non-specific protein adsorption, which is the first step in the foreign body reaction [37]. |

| Lack of tissue-specific cues | - Immunostaining for key extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins and integrins at the interface. | Functionalize the surface with bioactive peptides (e.g., RGD) derived from ECM proteins to promote specific cell adhesion and signaling, encouraging integration over isolation [37]. |

| Bacterial colonization & infection | - Use microbial culture or DNA sequencing on explanted devices. - Perform in vitro antimicrobial adhesion assays. | Implement an antimicrobial coating strategy, either by incorporating contact-killing agents (e.g., silver nanoparticles) or a drug-delivery system for controlled release of antibiotics [38]. |

Issue 3: Inconsistent Coating Performance Across Batches

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Potential Surface Engineering Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Uncontrolled coating deposition parameters | - Review process logs for variability in temperature, pressure, or deposition rate. - Use spectroscopic ellipsometry to measure coating thickness uniformity. | Establish and adhere to a strict Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) with real-time monitoring of key deposition parameters. |

| Substrate surface contamination | - Perform surface analysis (XPS, AES) before coating to detect organic or inorganic contaminants. | Implement a rigorous and validated substrate cleaning protocol (e.g., plasma cleaning, solvent cleaning) prior to coating deposition. |

| Inadequate quality control metrics | - Statistically analyze coating performance data (e.g., adhesion, composition) against in vivo outcomes. | Introduce additional characterization checkpoints, such as consistent measurement of coating thickness, adhesion, and chemical composition before proceeding to in vivo testing [39]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Implant Surface and Immune Modulation Research

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Protein NPs (e.g., eOD-GT8 60mer) | These protein nanoparticles, with a size optimized for lymphatic uptake, can be used as a platform to deliver immunomodulatory signals (e.g., antigens) directly to lymph nodes to steer the adaptive immune response [41]. |