Organic Electrochemical Transistors for Biosensing: Principles, Advances, and Clinical Applications

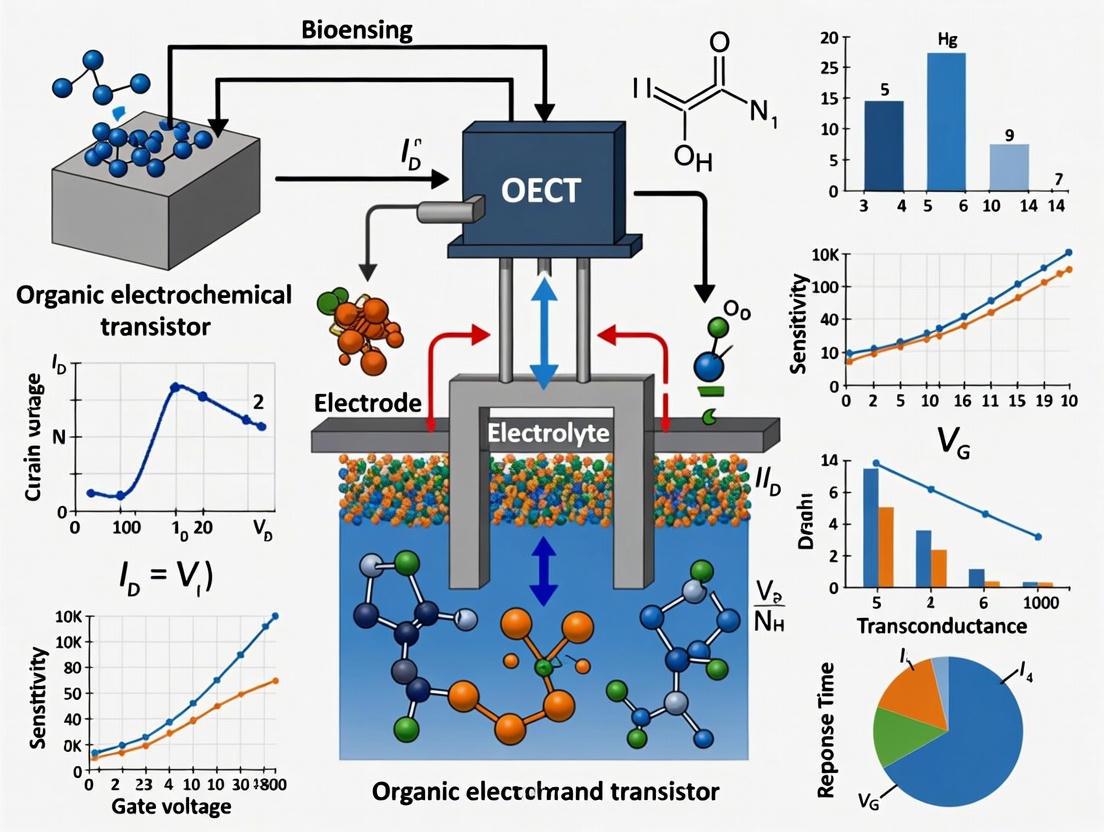

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Organic Electrochemical Transistors (OECTs) as a transformative technology in biosensing.

Organic Electrochemical Transistors for Biosensing: Principles, Advances, and Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Organic Electrochemical Transistors (OECTs) as a transformative technology in biosensing. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental operating principles of OECTs, including the Bernards model and ionic/electronic charge coupling. The review delves into cutting-edge fabrication methodologies, such as flexible printed circuit board (fPCB) and inkjet printing for scalable, low-cost production. It critically examines device functionalization strategies—including gate, channel, and electrolyte modification—for detecting targets from small molecules to proteins and DNA. The content further addresses key challenges in sensor stability, reusability, and integration into wearable and point-of-care platforms, offering troubleshooting and optimization insights. By synthesizing recent advances and performance validation, this article serves as a foundational resource for developing next-generation bioelectronic devices for clinical diagnostics and personalized medicine.

The Foundation of OECTs: Unraveling Principles, Materials, and Biosensing Mechanisms

The organic electrochemical transistor (OECT) has emerged as a premier transducer in bioelectronics, renowned for its ability to effectively interface biological environments with electronic readout systems. Its operation hinges on the mixed ionic and electronic conduction within an organic semiconductor channel, allowing it to convert ionic fluxes from biological events into amplified electronic signals [1] [2]. This unique capability, combined with low operational voltages (typically < 1 V), inherent biocompatibility, and mechanical flexibility, makes the OECT an exceptionally versatile platform for a wide range of applications, from biosensing and neuromorphic computing to electrophysiological recording [3] [4] [5].

At the heart of the OECT's functionality is its fundamental structure, comprising three electrodes—gate, source, and drain—and an organic semiconductor channel, all interfaced through an electrolyte [2]. This configuration facilitates a bulk interaction between ions from the electrolyte and electronic charges in the channel, leading to high transconductance (gm), a key metric for signal amplification [1]. This article provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols centered on the basic OECT configuration, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the foundational knowledge and methodologies necessary to leverage this technology in advanced biosensing research.

OECT Device Architecture and Operational Principle

Core Components and Configuration

A typical OECT is constructed from several key components, each playing a critical role in its operation. The spatial arrangement of these components can be adapted into various architectures (e.g., planar, stacked) to suit specific application needs [1].

- Channel: The channel, typically a thin film of an organic mixed ionic-electronic conductor (OMIEC), bridges the source and drain electrodes. Its conductivity is modulated by the injection of ions from the electrolyte. The most common channel material is the conducting polymer poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrene-sulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS), which operates in depletion mode [2]. Other OMIECs, including both p-type and n-type materials, are also employed [5].

- Source and Drain Electrodes: These are electronically conducting contacts (often made of gold or other inert metals) that allow a drain current (I

DS) to flow through the channel. The source is typically held at ground potential [2]. - Gate Electrode: The gate electrode is in ionic contact with the channel via the electrolyte. It can be a polarizable electrode (e.g., Pt, Au) or a non-polarizable electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl). Applying a voltage (V

GS) to the gate electrode drives ions into or out of the channel [5] [1]. - Electrolyte: The electrolyte, which can be a liquid, gel, or solid, contains mobile ions and serves as the dielectric medium connecting the gate and the channel [1]. Its composition and concentration can significantly influence device performance.

The following diagram illustrates the operational principle of a standard depletion-mode OECT, such as one based on PEDOT:PSS.

Operational Mechanism and Sensing Principle

The operation of an OECT can be understood through the interplay of two coupled circuits: an electronic circuit (source-channel-drain) and an ionic circuit (gate-electrolyte-channel) [3]. The channel acts as a resistor whose conductivity is governed by its doping level, which is in turn controlled by the migration of ions from the electrolyte.

In a classic depletion-mode OECT using PEDOT:PSS:

- At zero gate voltage (V

GS= 0 V), the channel is highly conductive (doped, or oxidized, in the case of PEDOT:PSS), and a significant drain current (IDS) flows. This is the ON state [2]. - Upon application of a positive gate voltage (V

GS> 0 V), cations from the electrolyte are driven into the bulk of the OMIEC channel. This influx of ions dedopes (reduces) the p-type semiconductor, decreasing its hole density and conductivity, thereby switching the transistor to the OFF state [4] [2].

The efficiency of this gating process is quantified by the transconductance, gm = ∂IDS/∂VGS, which represents the amplification capability of the device. The Bernards and Malliaras model provides a foundational framework for understanding OECT operation, linking gm to material properties and device geometry [5] [3].

For biosensing, the presence or reaction of a target analyte can be transduced into an electrical signal through several mechanisms, primarily by affecting the effective gate voltage or the channel's doping state [5]. The most common strategy is gate functionalization, where a biorecognition element (e.g., an enzyme, antibody, or aptamer) is immobilized on the gate electrode. When the target analyte interacts with this functionalized gate, it induces a change in the gate potential, which modulates IDS, allowing for highly sensitive detection [5] [6].

Performance Characteristics and Key Metrics

The performance of an OECT is evaluated through its electrical characteristics and key figures of merit, which are crucial for benchmarking and optimizing devices for specific applications.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for OECT Characterization

| Metric | Symbol | Description | Measurement Method | Typical Values/Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer Characteristics | IDS vs. VGS |

Shows the dependence of drain current on gate voltage at a constant drain voltage (VDS). |

Sweep VGS while measuring IDS at fixed VDS. |

Used to determine operating regime and ION/IOFF ratio [4]. |

| Output Characteristics | IDS vs. VDS |

Shows the dependence of drain current on drain voltage at different fixed gate voltages. | Sweep VDS while measuring IDS at fixed VGS steps. |

Reveals the transistor's saturation behavior [4]. |

| Transconductance | gm |

Figure of merit for signal amplification efficiency; the rate of change of IDS with respect to VGS. |

gm = ∂IDS/∂VGS, derived from transfer curve. |

High gm (>10 mS reported) is desirable for sensitive detection [5] [1]. Governed by µC*, geometry (W, L, d) [5]. |

| On/Off Ratio | ION/IOFF |

The ratio between the maximum and minimum channel current. | Extracted from the transfer curve. | Values ~1000 are achievable, important for switching applications [4]. |

| Volumetric Capacitance | C* | The capacitance per unit volume of the channel material, indicating its ion uptake capacity. | Calculated from OECT response or measured via electrochemical impedance spectroscopy [1]. | A high C* is critical for achieving high gm [1]. |

| Response Time | Ï„ | The speed at which the OECT switches between ON and OFF states. | Measured from the transient current response to a gate voltage pulse. | Ranges from microseconds (liquid electrolytes) to slower times (gels); limited by ion transport [3] [2]. |

| Cycle Stability | - | The ability of the device to maintain performance over repeated gating cycles. | Monitor transfer curves or transient response over many cycles (e.g., 60+ cycles). | Indicates operational robustness and is influenced by material stability and ion gel electrolytes [4]. |

Table 2: Impact of OECT Design Parameters on Device Performance

| Parameter | Impact on Performance | Considerations for Biosensing |

|---|---|---|

| Channel Dimensions (W, L, d) | gm ∠(W⋅d)/L [5]. A thicker, wider, and shorter channel maximizes gm. |

Miniaturization (small W, L) is key for high-density arrays and spatial resolution in sensing [4]. |

| Gate Electrode Type & Area | Non-polarizable gates (Ag/AgCl) allow for smaller gate areas. Polarizable gates (Au, Pt) require a large area (Cgate >> Cchannel) [5] [6]. |

The gate is often the functionalization site. A large, porous gate can enhance sensitivity [5]. |

| Electrolyte Composition | Ionic concentration and type affect mobility, Debye length, and device kinetics. | Biological fluids (saliva, sweat, blood) serve as electrolytes, making OECTs suitable for direct monitoring [1] [7]. |

| Channel Material | OMIEC properties (µ, C*) directly define gm and speed. |

PEDOT:PSS is common; new OMIECs are developed for stability, n-type operation, and specific sensing functions [5] [1]. |

Experimental Protocols for OECT Fabrication and Characterization

This section provides a detailed methodology for fabricating a flexible OECT array using a hybrid fPCB and inkjet printing approach, and for characterizing its critical performance metrics.

Protocol: Fabrication of Flexible OECT Arrays via fPCB and Inkjet Printing

This protocol outlines a rapid, low-cost method for fabricating flexible, all-solid-state OECTs, suitable for wearable biosensing applications [4].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for fPCB-based OECT Fabrication

| Item | Specification / Function |

|---|---|

| Flexible PCB Substrate | Polyimide (PI) substrate with photolithographically patterned Cu electrodes (thickness: ~35 µm). Serves as the mechanical support and source/drain/gate interconnects [4]. |

| Gold Plating Solution | Used to electroplate a thin layer (~20 nm) on Cu electrodes to protect against redox reactions and improve stability [4]. |

| PEDOT:PSS Ink | Commercially available or customized conducting polymer dispersion. Forms the OMIEC channel. Crosslinkers (e.g., GOPS) may be added to improve adhesion to the substrate [4]. |

| Gel Electrolyte | Non-aqueous poly(ethylene glycol) acrylate (PEA) based gel. Serves as the solid-state ion reservoir, prevents leakage and enhances mechanical stability [4]. |

| Inkjet Printer | Customizable piezoelectric printer for patterning the PEDOT:PSS channel and gel electrolyte with precise alignment (feature size down to 100 µm) [4]. |

| Encapsulation Layer | A second layer of polyimide (PI) to insulate the interconnects and define the active areas [4]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

fPCB Electrode Fabrication:

- Pattern source, drain, gate electrodes, and interconnects on a polyimide substrate using standard photolithographic fPCB manufacturing processes.

- Electroplate a 20 nm gold layer onto the copper traces to enhance electrochemical stability.

- Apply a second polyimide layer to encapsulate the interconnects, leaving the electrode contact pads and active areas exposed [4].

Channel Patterning via Inkjet Printing:

- Prepare the PEDOT:PSS ink, optionally adding a crosslinker like (3-Glycidyloxypropyl)trimethoxysilane (GOPS) to a concentration of 1% v/v to improve film formation and adhesion.

- Using the inkjet printer, precisely deposit the PEDOT:PSS ink to form the transistor channel between the source and drain electrodes. A typical channel dimension is 100 µm (length) x 100 µm (width).

- Cure the printed PEDOT:PSS film according to the manufacturer's specifications (e.g., on a hotplate at 120°C for 60 minutes) to remove residual solvents and complete the crosslinking process [4].

Solid-State Electrolyte Patterning:

- Prepare the gel electrolyte precursor (e.g., PEA with ionic liquid or salt).

- Inkjet print the gel electrolyte onto the device to cover the overlap between the gate electrode and the OMIEC channel.

- Expose the device to UV light for polymerization to form the final solid-state gel electrolyte [4].

Quality Control:

- Inspect the fabricated devices under an optical microscope to check for printing defects, misalignment, or short circuits.

- Electrically test each unit in the array for basic functionality before proceeding to full characterization.

The following workflow diagram summarizes the fabrication process.

Protocol: Electrical Characterization of OECT Performance

This protocol describes the standard procedures for characterizing the steady-state and dynamic performance of an OECT.

Equipment and Software

- Source Measure Unit (SMU) or Potentiostat with multiple channels.

- Probe station for connecting to the OECT terminals.

- Faraday cage (recommended for low-noise measurements).

- Computer with data acquisition and analysis software (e.g., LabVIEW, Python, or MATLAB).

Step-by-Step Characterization Procedure

Setup:

- Place the OECT in a Faraday cage to minimize electrical noise.

- Connect the source, drain, and gate electrodes to the SMU.

- If using a liquid electrolyte, ensure the gate and channel are properly immersed. For gel electrolytes, ensure good contact.

Output Characteristics (I

DSvs. VDS):- Set the gate voltage (V

GS) to a constant value (e.g., 0 V). - Sweep the drain voltage (V

DS) from 0 V to a predetermined maximum (e.g., -0.6 V for a PEDOT:PSS OECT) while measuring the resulting drain current (IDS). - Repeat this sweep for several different, fixed V

GSvalues (e.g., 0 V, 0.2 V, 0.4 V, 0.6 V) [4].

- Set the gate voltage (V

Transfer Characteristics (I

DSvs. VGS) and Transconductance (gm):- Set the drain voltage (V

DS) to a constant value within the device's operational range (e.g., -0.3 V). - Sweep the gate voltage (V

GS) through the relevant voltage window (e.g., from -0.2 V to +0.8 V) while measuring IDS. - The transconductance (g

m) is calculated as the numerical derivative of the IDS-VGScurve. Plot gmas a function of VGSto identify the gate voltage for maximum amplification [4] [5].

- Set the drain voltage (V

Transient Response and Switching Speed:

- Apply a constant drain voltage (V

DS). - Apply a square-wave pulse train to the gate electrode. The pulse should alternate between voltages corresponding to the ON and OFF states (e.g., 0 V and 0.6 V), with a defined pulse width and frequency.

- Measure the resulting I

DSover time. The response time (Ï„) is typically defined as the time taken for the current to change from 10% to 90% of its maximum swing (or vice versa) upon the application of a gate pulse [4].

- Apply a constant drain voltage (V

Cyclic Stability Test:

- Continuously cycle the gate voltage (e.g., for 60 cycles or more) as in step 3 or apply repeated gate pulses as in step 4.

- Monitor the change in I

DSor the transfer curve over these cycles to assess the device's operational stability and reversibility [4].

Flexibility and Bending Tests (for flexible devices):

- Mount the OECT on testbeds with known, varying bending radii.

- Repeat the transfer characteristic measurements (Step 3) at each bending state.

- Compare key parameters (e.g., I

DS, gm) in the flat and bent states to evaluate mechanical robustness [4].

Troubleshooting and Common Experimental Challenges

Even with a standardized protocol, researchers may encounter specific issues during OECT fabrication and characterization. The table below outlines common problems, their potential causes, and recommended solutions.

Table 4: OECT Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Causes | Suggested Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High Device-to-Device Variation | Inconsistent channel printing; non-uniform electrolyte deposition; substrate surface contamination. | Optimize inkjet printing parameters (waveform, drop spacing); implement surface plasma treatment prior to printing; statistically characterize large arrays [4]. |

| Poor Operational Stability / Hysteresis | Electrochemical degradation of materials; delamination of functional layers; unstable gate electrode. | Use gel electrolytes to protect metal electrodes (e.g., Cu) [4]; incorporate crosslinkers in polymer inks [4]; use stable gate materials like Ag/AgCl or large surface area PEDOT:PSS gates [5]. |

| Slow Transient Response | Slow ion transport in the channel material or gel electrolyte; large channel dimensions. | Use OMIECs with high ionic mobility; reduce channel thickness and length; consider liquid electrolytes for faster operation [3] [1]. |

Low Transconductance (gm) |

Poor OMIEC properties (low µ or C*); suboptimal device geometry; inappropriate gate electrode. | Increase channel volumetric capacitance (C*); optimize geometry (increase W⋅d/L) [5]; ensure gate capacitance is much larger than channel capacitance [6]. |

| Noisy Signal | Unstable electrical connections; fluctuating electrochemical reactions; environmental interference. | Ensure good contact with probes; use a Faraday cage; employ stable, non-polarizable gate electrodes where possible [1]. |

The Bernards Model (also referred to as the Bernards-Malliaras model) provides a foundational theoretical framework for understanding the operating principles of Organic Electrochemical Transistors (OECTs) [8]. This model is particularly crucial for interpreting how OECTs transduce ionic signals from an electrolyte into electronic currents in a semiconductor channel, a core mechanism that makes OECTs exceptionally suitable for biosensing applications [1]. The model simplifies the complex electrochemical processes into more familiar electrical components, treating the OECT as two coupled circuits: an ionic circuit and an electronic circuit [8].

For researchers in biosensing and drug development, this conceptual separation is powerful. It enables the quantitative analysis of device parameters, allowing for the design of highly sensitive biosensors that can detect biomarkers, neurotransmitters, and other biological analytes [1] [9]. The model explains the unique amplification capability of OECTs, where a small ionic flux (e.g., from a biochemical binding event) can modulate a large electronic current, thereby providing highly sensitive detection of weak biological signals [1].

Theoretical Foundations of the Model

Core Principles and Circuit Decoupling

The Bernards Model rests on several key physical assumptions that allow for the decoupling of ionic and electronic transport [8]. First, it posits that ions injected from the electrolyte into the organic mixed ionic-electronic conductor (OMIEC) channel do not undergo Faradaic reactions with the polymer material itself. Instead, they act as immobile counter-ions that electrostatically compensate for electronic charges. This process is fundamentally capacitive in nature.

The model therefore conceptualizes an OECT as consisting of two distinct sub-circuits:

- The Electronic Circuit: The flow of electronic charge (holes in p-type devices) through the semiconducting polymer channel from the source to the drain electrodes. This circuit is treated as a simple resistor, where the conductivity is modulated by the presence of ions.

- The Ionic Circuit: The movement of ions within the electrolyte and their injection into the channel material. The channel itself, where ions compensate for electronic charges, is modeled as a bulk capacitance [8].

At steady state, when the gate voltage is applied and ions have finished moving into the channel, this capacitive element becomes fully charged, and the gate current drops to zero. This decoupled approach has been highly successful in fitting the steady-state output characteristics of OECTs.

Governing Equations and Key Parameters

For a p-type OECT operating in depletion mode, the Bernards Model describes the channel current (ICH) with a piecewise function, similar to a MOSFET model [8]:

For VD > VG - VT: ICH = μC* (W/d/L) [ (VT - VG) + (1/2)VD ] VD

For VD < VG - VT: ICH = - μC* (W/d/L) [ (VG - VT)2 / 2 ]

Where:

- μ is the charge carrier mobility (cm² Vâ»Â¹ sâ»Â¹)

- C* is the volumetric capacitance (F cmâ»Â³) of the channel material

- W, d, L are the width, thickness, and length of the channel, respectively

- VG and VD are the gate and drain voltages, respectively

- VT is the threshold voltage

A central figure of merit derived from this model is the transconductance, gm, which quantifies the amplification capability of the OECT. It is defined as the derivative of the channel current with respect to the gate voltage (gm = ∂ICH/∂VG). The product μC* is a critical material property that determines the ultimate performance of the OECT [8].

Table 1: Key Parameters in the Bernards Model and Their Physical Significance

| Parameter | Symbol | Unit | Physical Significance | Impact on OECT Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volumetric Capacitance | C * | F cmâ»Â³ | Measures the capacity of the channel to store ions per unit volume. | Higher value enables greater current modulation and higher transconductance. |

| Charge Carrier Mobility | μ | cm² Vâ»Â¹ sâ»Â¹ | Describes how quickly electronic charges can move through the material. | Higher value leads to faster electronic response and higher current. |

| Geometry Factor | Wd/L* | Unitless | Aspect ratio of the OECT channel. | A larger Wd/L* increases the magnitude of the channel current. |

| Transconductance | gm | S | Ratio of output current change to input voltage change. | Key metric for signal amplification; higher is better for sensitive biosensing. |

Experimental Validation and Protocol

Validating the Bernards Model requires characterizing the steady-state electrical performance of an OECT. The following protocol outlines the key measurements and the procedure for extracting critical parameters.

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for OECT Fabrication and Characterization

| Item | Function/Description | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Conducting Polymer | Forms the OMIEC channel; transports electronic charges and hosts ions. | PEDOT:PSS dispersion; p(g2T-T) or BBL for n-type operation [4] [10]. |

| Electrolyte | Medium for ionic transport; bridges the gate and the channel. | Aqueous saline (e.g., 0.1 M NaCl), gel electrolyte (e.g., PEA-based), or ionic liquid [4] [1]. |

| Gate Electrode | Provides the input voltage to drive ions into the channel. | Au, Pt, or Ag/AgCl for stable electrochemical window [1]. |

| Substrate | Mechanical support for the OECT. | Rigid (e.g., glass) or flexible (e.g., polyimide, fPCB) [4]. |

| Source/Drain Electrodes | Provide ohmic contact for electronic current injection/collection. | Au or Au-coated electrodes (e.g., on fPCB) to ensure stability [4]. |

| Crosslinker | Enhances adhesion of polymer and gel layers to substrates, improving mechanical stability. | Added to PEDOT:PSS or gel electrolytes for flexible devices [4]. |

Protocol: OECT Characterization and Parameter Extraction

Step 1: Device Fabrication

- Substrate Preparation: Begin with a cleaned and patterned substrate. Flexible printed circuit board (fPCB) technology offers a rapid, low-cost method for fabricating source, drain, and gate electrodes on a polyimide substrate [4].

- Channel Patterning: Deposit the OMIEC channel material (e.g., PEDOT:PSS) between the source and drain electrodes. Inkjet printing is a scalable method suitable for this purpose. For all-solid-state devices, add a crosslinker to the polymer solution to improve adhesion and prevent delamination [4].

- Electrolyte Integration: For gel-gated OECTs, deposit the gel electrolyte (e.g., PEA-based) over the channel and gate electrode using a customizable inkjet printer, ensuring proper alignment [4].

Step 2: Output and Transfer Curve Measurement

- Output Characteristics: Sweep the drain voltage (VD) from 0 V to a maximum value (e.g., -0.6 V for a p-type device) while stepping the gate voltage (VG) through a range of values (e.g., from 0.2 V to 0.8 V). Measure the resulting channel current (ICH) [4].

- Transfer Characteristics: At a fixed drain voltage (e.g., VD = -0.3 V), sweep the gate voltage and measure the channel current. This curve is used to extract the transconductance.

Step 3: Data Analysis and Parameter Extraction

- Extract Transconductance (gm): Calculate gm by differentiating the transfer curve (ICH vs. VG) at a specific VD.

- Calculate Mobility (μ) and Capacitance (C*): Fit the output characteristic data to the Bernards Model equations (Section 2.2). The mobility and volumetric capacitance can be extracted from this fitting procedure [4] [8]. For example, a reported fPCB-fabricated OECT exhibited a mobility of 1.1 cm² Vâ»Â¹ sâ»Â¹ calculated using this model [4].

Applications in Biosensing and Beyond

The Bernards Model provides the theoretical backbone for designing and optimizing OECTs for a wide range of applications, particularly in biosensing.

- High-Sensitivity Biomarker Detection: The model's focus on transconductance guides the design of OECTs for amplifying weak electrical signals from biological binding events. This has enabled the detection of neurotransmitters like catecholamine at nanomolar concentrations [1], and the sensing of glucose in sweat and other biofluids using enzymatic or molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) functionalized gates [11] [9].

- Neuromorphic Computing: The ionic dynamics described by the Bernards Model are harnessed to create devices that mimic synaptic behavior. The transient response of the channel current to gate voltage pulses can emulate short-term and long-term plasticity, forming the basis for artificial synapses and organic electrochemical random-access memories (ECRAMs) [8]. Recent work on flexible, all-gel OECTs has demonstrated their use in neuromorphic simulation for tactile perception in robotic hands [10].

- Wearable and Implantable Sensors: The understanding of device physics allows for the creation of OECTs on flexible substrates like fPCB or stretchable all-gel networks [4] [10]. These devices maintain performance under mechanical deformation, enabling their use as conformal biosensors for continuous health monitoring, such as lactate sensing in sweat to indicate muscle fatigue [9].

Current Limitations and Future Perspectives

While the Bernards Model is an excellent tool for predicting steady-state OECT behavior, it has limitations, particularly concerning transient response. The model's assumption of a purely capacitive ionic-electronic coupling does not fully capture the complex, time-dependent ion dynamics that govern switching speed and non-volatile memory behavior [8].

Future research is focused on bridging this gap by developing more comprehensive models that account for:

- Ion Transport Kinetics: The diffusion and drift of ions within the complex nano-morphology of the OMIEC, which can be the speed-limiting factor [8].

- Electrochemical Doping and Swelling: The impact of water uptake and volumetric swelling of the channel material on ion transport and electronic mobility [1].

- Structural Evolution: Real-time changes in the polymer's microstructure (e.g., π-π stacking distance) during operation that can alter transport properties [8].

Advances in operando characterization techniques and multi-physics modeling will be crucial to develop a more unified understanding, ultimately accelerating the design of next-generation OECTs for high-speed biosensing and neuromorphic computing applications.

Organic Electrochemical Transistors (OECTs) have emerged as a preeminent technology in biosensing due to their high signal-to-noise ratio, low operating voltage, and exceptional biocompatibility [12] [13]. The performance of OECT-based biosensors is critically dependent on their ability to efficiently convert a biological event into an amplified, measurable electrical signal. The central metric quantifying this amplification capability is transconductance (gm).

Transconductance, defined as gm = ∂ID/∂VG, represents the efficiency with which a small change in gate voltage (VG) modulates the drain current (ID) [13]. A higher transconductance signifies a greater amplification factor, enabling the sensor to detect weaker biological signals with higher sensitivity, which is paramount for detecting low-abundance biomarkers, neurotransmitters, and ions in complex physiological environments [14].

In OECTs, this amplification stems from a unique mixed ionic-electronic conduction process. When a gate voltage is applied, ions from the electrolyte migrate into the bulk of the organic semiconductor channel, modulating its doping level and electronic conductivity [15] [16]. This volumetric capacitance, distinct from the interfacial capacitance in traditional field-effect transistors, is the origin of OECTs' high transconductance and superior performance in aqueous, biological milieus [12].

Quantitative Relationship Between gm and Biosensor Performance

The sensitivity of an OECT biosensor is directly governed by its transconductance. The fundamental equation defining the maximum transconductance is [13]:

gm = (Wd / L) * μ * C* * (VTh - VG)

This equation reveals that gm is not an intrinsic property of the channel material alone but a function of both device geometry (W, d, L) and material properties (μ, C). The product μC serves as a valuable material quality factor, allowing for a geometry-independent comparison of different organic mixed ionic-electronic conductors (OMIECs) [13].

Table 1: Key Parameters Influencing OECT Transconductance and Sensor Sensitivity.

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Impact on gm and Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Channel Width | W | Width of the conducting channel. | Increasing W raises gm, enhancing current drive and signal amplitude [13]. |

| Channel Length | L | Distance between source and drain electrodes. | Decreasing L increases the W/L ratio, significantly boosting gm [13]. |

| Channel Thickness | d | Thickness of the organic semiconductor film. | Increasing d raises gm but can slow the device's response time [13]. |

| Carrier Mobility | μ | How quickly charges move through the material. | Higher μ leads to higher gm, improving switching speed and amplification [13]. |

| Volumetric Capacitance | C* | Ability of the channel to store ions per unit volume. | A higher C* enables a greater doping change per gate voltage, maximizing gm [12] [16]. |

| Material Quality Factor | μC* | Product of mobility and volumetric capacitance. | A high μC* is essential for achieving high-gm devices without relying solely on geometry [13]. |

For fiber-based OECTs (F-OECTs), the geometric considerations differ. The channel width W is determined by the circumference of the fiber (Ï€d), which is inherently larger than the width of a planar channel with the same footprint. This allows F-OECTs to achieve very high W/L ratios, resulting in superior transconductance and current-driving capability compared to their planar counterparts [12].

The ultimate sensitivity of a biosensor, often defined by its Limit of Detection (LOD), is a function of the signal-to-noise ratio. A high gm provides greater signal amplification for a given biological binding event, thereby lowering the LOD. This has been demonstrated in sensors for dopamine, where OECTs with optimized transconductance have achieved detection limits in the nanomolar range [14].

Experimental Protocols for Transconductance Characterization

Accurate characterization of transconductance is a prerequisite for developing and validating high-performance OECT biosensors. The following protocol details the standard measurement procedure.

Equipment and Reagent Setup

- OECT Device: A fabricated OECT with defined channel geometry (W, L, d).

- Source Measure Units (SMUs): A semiconductor parameter analyzer or a combination of two precision source-measure units to independently control VG and VD while measuring ID.

- Electrolyte: A suitable aqueous electrolyte, such as phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at physiological concentration (e.g., 0.1 M), to mimic biological conditions [16].

- Electrochemical Cell: A probe station or a custom fluidic cell that allows stable contact between the electrolyte and the OECT's gate and channel.

- Faraday Cage: (Recommended) To minimize external electromagnetic interference during sensitive measurements.

Step-by-Step Measurement Procedure

- Device Immersion & Stabilization: Immerse the OECT's gate and channel in the electrolyte solution. Allow the device to stabilize for a predetermined period (e.g., 15-30 minutes) until the open-channel current (IDS) reaches a steady state, indicating stable electrolyte/channel interaction.

- Output Curve Measurement:

- Set the gate voltage (VG) to a starting value (e.g., 0 V).

- Sweep the drain voltage (VD) from 0 V to a low voltage, typically -0.6 V or -0.8 V, to avoid electrochemical side reactions.

- Record the corresponding drain current (IDS) at each VD step.

- Repeat this sweep for a series of VG values (e.g., 0 V, 0.2 V, 0.4 V, 0.6 V).

- Output: A family of IDS vs. VD curves used to verify proper transistor operation and identify the linear/saturation regimes.

- Transfer Curve Measurement & gm Extraction:

- Set the drain voltage (VD) to a constant value within the saturation region (e.g., -0.6 V).

- Sweep the gate voltage (VG) across the desired operating range (e.g., from 0 V to 0.8 V).

- Record the corresponding drain current (IDS) at each VG step.

- Data Processing: The transconductance (gm) is calculated as the first derivative of the transfer curve: gm = ∂IDS/∂VG. This is typically done using numerical differentiation of the IDS vs. VG data.

- Output: A transfer curve (IDS vs. VG) and its corresponding gm vs. VG plot, which identifies the peak transconductance (gm,max) and the optimal gate voltage for sensor operation.

- Validation with Model: For depletion-mode PEDOT:PSS OECTs, validate the data by fitting the transfer curve in the saturation region to the equation: IDS = [-q μ p0 t W / (2 L Vp)] * (VG - Vp)^2, where Vp is the pinch-off voltage [12].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for the characterization of OECT transconductance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development of high-transconductance OECTs relies on a specific set of materials and reagents, each serving a critical function in device fabrication and operation.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for OECT Biosensor Development.

| Category | Material/Reagent | Function in OECTs | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Channel Material | PEDOT:PSS | The most common p-type OMIEC; serves as the electroactive channel where doping modulation occurs [13]. | High conductivity formulations; often requires secondary doping (e.g., with ethylene glycol) for enhanced performance [13]. |

| N-type Polymers | e.g., BBL, p(g2T-TT), p(g2T-TTT) | Enable n-type (electron-conducting) OECT operation and the development of complementary logic circuits [15]. | Developing stable, high-mobility n-type materials in aqueous environments is a key research area [15]. |

| Liquid Electrolyte | Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Standard aqueous electrolyte for in-vitro testing; provides mobile ions (Na+, K+, Cl-) for gating the channel [12]. | Ion concentration and type influence capacitance and device dynamics [12]. Prone to evaporation [16]. |

| Gel Electrolyte | Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) / Salt composites | Solid-state electrolyte; prevents leakage, enhances device stability and flexibility for wearable applications [16]. | Ionic conductivity must be maintained; mechanical properties should match biological tissues for implants [16]. |

| Hydrogels | PEG, PHEMA, Chitosan | Biocompatible, tissue-like solid electrolytes; ideal for implantable and wearable biosensors due to their soft, hydrating nature [16]. | Can be engineered with self-healing, adhesive, or stimuli-responsive properties [16]. |

| Gate Electrode | Ag/AgCl, Gold (Au), Platinum (Pt) | The gate electrode applies the potential to the electrolyte. Ag/AgCl is a non-polarizable reference, while Au/Pt are polarizable [12] [14]. | Material choice affects gate capacitance and stability. Surface modification is often used to enhance selectivity [14]. |

| Functionalization Agent | 1-pyrenebutyric acid N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (PBASE) | A common linker molecule for immobilizing biorecognition elements (e.g., antibodies) on graphene or carbon-based gate electrodes [17]. | Enables covalent bonding of biomolecules, creating a specific sensing interface on the device [17]. |

| 3α-Dihydrocadambine | 3α-Dihydrocadambine, MF:C27H32N2O10, MW:544.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Delavinone | Delavinone, MF:C27H43NO2, MW:413.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Considerations and Material Design for Enhanced gm

Beyond geometric scaling, the strategic design of materials and device architecture is crucial for pushing the limits of transconductance and sensitivity.

Material Engineering for High μC*

The pursuit of a high material quality factor (μC*) is central to modern OECT research [13]. Innovations in organic semiconductor synthesis focus on:

- Improving Ionic Permeability: Designing polymer backbones with enhanced volumetric capacitance (C*) by facilitating easier ion penetration and more efficient electrochemical doping/dedoping [15].

- Enhancing Charge Transport Mobility (μ): Developing new conjugated polymers with more ordered microstructures and reduced energetic disorder to boost charge carrier mobility [13].

Device Architecture and Ion Transport

The physical structure of the OECT profoundly influences its performance. In fiber-based OECTs (F-OECTs), the three-dimensional architecture (e.g., twisted, coaxial) creates new pathways for ion transport. A mechanism known as Lateral Insertion-assisted ion transport allows ions to diffuse both vertically and laterally along the fiber, which can significantly reduce ion diffusion time and improve the device's response speed, thereby enhancing the effective gm for dynamic signals [15].

Operational Mode: Depletion vs. Accumulation

Most common PEDOT:PSS OECTs operate in depletion mode, where the channel is conductive at VG=0 and is switched "off" by a positive gate voltage [12] [15]. Conversely, accumulation-mode OECTs, often based on n-type polymers, start in an "off" state and are turned "on" by the gate voltage. Accumulation-mode devices are particularly advantageous for low-power applications and can achieve high ON/OFF ratios, which is beneficial for digital sensing and neuromorphic computing [15].

Organic Mixed Ionic-Electronic Conductors (OMIECs) are carbon-based materials capable of efficiently transporting and coupling both ionic and electronic charges, making them fundamental to the operation of Organic Electrochemical Transistors (OECTs) [18]. In OECTs, which are three-terminal devices, an OMIEC film forms the channel between the source and drain electrodes. This channel is in direct contact with an electrolyte, which serves as the gate dielectric. The application of a gate voltage drives ions from the electrolyte into the bulk of the OMIEC channel, thereby electrochemically modulating its doping state and electronic conductivity [15] [16]. This mixed conduction mechanism enables OECTs to excel in biosensing applications, offering high transconductance, low operating voltages, biocompatibility, and the ability to amplify small biological signals [19] [5].

Key OMIEC Materials and Their Performance

The performance of an OECT is largely dictated by the properties of its OMIEC channel material. The key figure of merit (FoM) for an OECT is the product of charge carrier mobility (µ) and volumetric capacitance (C*), which determines the transconductance and signal amplification capability [16]. Researchers have developed and characterized a wide range of OMIECs, from benchmark materials like PEDOT:PSS to novel synthetic polymers and blends.

Table 1: Comparison of Key OMIEC Channel Materials for OECTs

| Material | Type/Operation Mode | Key Performance Metrics | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS [18] [20] [21] | p-type, Depletion | µC* ≈ 1500 F cmâ»Â¹ Vâ»Â¹ sâ»Â¹ [16]; Transconductance up to 11±3 mS [18] | High conductivity, biocompatibility, commercial availability, facile processing | Limited volumetric capacitance, requires crosslinking for stability in water |

| PEDOT:ClOâ‚„ [21] | p-type, Depletion | High cycling stability (>1000 cycles); Performance stable under mechanical strain [21] | Small, mobile dopant enables stable performance; Suitable for flexible electronics | Requires electropolymerization |

| Melanin/PEDOT:PSS Blend [18] | p-type, Depletion | Transconductance: 11±3 mS (vs. 7±1 mS for pure PEDOT:PSS); 10x increase in C* [18] | Enhanced ionic-electronic coupling; Sustainable, bio-inspired component | Processability challenges at high melanin concentrations |

| PANI:DBSA [20] | p-type | N/A | Inexpensive raw materials; Good film smoothness and reproducibility | Lower conductivity and transconductance than PEDOT:PSS |

| PBTI2g-DTCN [22] | n-type, Accumulation | µC* = 287.8 F cmâ»Â¹ Vâ»Â¹ sâ»Â¹; Electron mobility: 0.84 cm² Vâ»Â¹ sâ»Â¹ [22] | High-performance n-type OMIEC; Excellent operational stability | Synthetic complexity |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section provides standardized protocols for fabricating and characterizing OECTs with different OMIEC channels, ensuring reproducibility and reliability in biosensing research.

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a Porous PEDOT:PSS OECT for 3D Cell Culture Monitoring

This protocol details the creation of a scaffold-like OECT with a porous PEDOT:PSS channel, ideal for hosting 3D cell cultures and monitoring cellular functions through ion fluxes and redox reactions [23].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Channel Cocktail: 1.0 wt% PEDOT:PSS (e.g., Orgacon ICP 1050) and 3.0 wt% (3-glycidyloxypropyl)trimethoxysilane (GOPS) in water [23].

- Electrode Substrate: Glass substrate with patterned Au source/drain electrodes (100 nm thickness, using Cr as adhesive layer). Channel width (W) = 1000 µm, length (L) = 10 µm [23].

- Gate Electrode: Ag/AgCl reference electrode in saturated KCl connected via a salt bridge [23].

- Measurement Electrolyte: 1X Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4 [23].

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Begin with a pre-patterned Au-on-glass substrate. Clean the substrate thoroughly to ensure good adhesion of the channel material.

- Channel Deposition: Deposit 5 µL of the prepared PEDOT:PSS/GOPS cocktail onto the channel area between the source and drain electrodes [23].

- Freezing: Immediately transfer the substrate to a -80 °C freezer and freeze for 1 hour. This step phase-separates the components to form the porous structure [23].

- Freeze-Drying: Place the frozen device in a freeze-dryer to remove the frozen solvent via sublimation, leaving a porous solid scaffold [23].

- Cross-Linking: Anneal the device at 120 °C for 1 hour to thermally cross-link the GOPS, stabilizing the porous structure and making it insoluble in aqueous solutions [23].

- Assembly: Attach a glass ring to the substrate to create a reservoir for the measurement solution or cell culture medium [23].

- Characterization: Use scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to confirm pore formation. The median pore diameter should be approximately 50 µm, suitable for cell infiltration [23].

Porous OECT Fabrication Workflow

Protocol 2: Fabrication of a High-Performance Planar PEDOT:PSS OECT

This protocol is optimized for producing high-quality, dense PEDOT:PSS films with excellent electrical characteristics for standard biosensing applications [20].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- PEDOT:PSS Solution: 5 mL commercial PEDOT:PSS dispersion (0.5-1 wt% in water).

- Additive Solutions: Ethylene glycol (150 µL, 3%), Dodecylbenzenesulfonic acid (DBSA, 12 µL, ~0.25%), and GOPS (50 µL, 1%) [20].

- Electrode Substrate: Glass slide with pre-patterned Au source/drain electrodes (L=130 µm, W=2 mm) [18].

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: To 5 mL of PEDOT:PSS dispersion, add ethylene glycol and DBSA. Stir and sonicate the mixture for 10 minutes. Then, add 50 µL of GOPS and stir for 1 minute with sonication [20].

- Substrate Cleaning: Clean the electrode substrate with DI water. Render it hydrophilic by irradiating with ozone plasma for 20 minutes [20].

- Spin-Coating: Drop 75 µL of the prepared PEDOT:PSS solution onto the channel. Let it sit for 100 seconds without spinning, then spin-coat at 3000 rpm for 40 seconds [20].

- Annealing and Cross-Linking: Anneal the film on a hotplate at 135 °C for 1 hour [20].

- Post-Treatment (Optional): Immerse the coated electrode in DI water for 18 hours to remove impurities and low-molecular-weight components, resulting in a smoother film surface [20].

- Electrical Characterization: Measure the OECT's output and transfer characteristics in PBS using a semiconductor parameter analyzer. Calculate conductivity and transconductance from the linear region of the output curve at V_G = 0 V and the peak of the transfer curve, respectively [20].

Protocol 3: Creating a Melanin/PEDOT:PSS Blend for Enhanced Capacitance

This protocol describes blending synthetic melanin with PEDOT:PSS to create a more sustainable OMIEC with superior ionic-electronic coupling and volumetric capacitance [18].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Synthetic Melanin (Mel): Synthesize water-soluble melanin by reacting 0.3 g of DL-DOPA in 60 mL Milli-Q water and 400 µL NH₄OH under 6 atm of O₂ for 6 hours. Purify via dialysis and dry at 90 °C [18].

- Mel/PEDOT:PSS Blends: Dilute the synthesized melanin powder directly into commercial PEDOT:PSS solution to create blends with 0, 10, 20, 30, and 50 wt% melanin content. Stir for 15 minutes and sonicate for 1 hour before film deposition [18].

Procedure:

- Material Synthesis: Follow the steps above to synthesize and purify water-soluble melanin [18].

- Blend Preparation: Create the desired Mel/PEDOT:PSS blends by weight. Note that blends with >50% melanin content show poor film processability [18].

- Device Fabrication: Fabricate OECTs using the spin-coating and annealing procedures outlined in Protocol 3.2.

- Performance Evaluation: Characterize the OECT performance. The optimal blend (e.g., 30% Mel) should show a significant increase in transconductance and volumetric capacitance compared to pure PEDOT:PSS devices [18].

Biosensing Applications and Mechanisms

OECTs functionalized with various OMIECs have been successfully deployed for a wide range of biosensing applications. The sensing mechanism typically relies on one of three strategies [5]:

- Gate Functionalization: The gate electrode is modified with receptors (e.g., enzymes, antibodies). The binding or reaction of the target analyte on the gate surface alters the effective gate potential, modulating the channel current [5].

- Channel-Electrolyte Interface Functionalization: The channel surface is functionalized so that the target analyte directly interacts with it, changing the channel's electronic structure or interface potential [5].

- Electrolyte Functionalization: The electrolyte itself is modified with sensing elements like enzymes or ion-selective membranes, which generate an ionic signal in response to the analyte that gates the transistor [5].

Table 2: OECT Biosensing Applications by Target Analyte

| Target Analyte | OMIEC Channel | Functionalization/Sensing Strategy | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cations (Kâº, Naâº, etc.) [23] | Porous PEDOT:PSS | Direct gating by cation injection into the channel. | Current response to concentration changes from 1 mM to 1 M [23]. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) [23] | Porous PEDOT:PSS | Direct redox reaction with the PEDOT channel. | Current response to concentrations from 0.01 to 1.3 wt% [23]. |

| Glucose, Lactate [5] | PEDOT:PSS | Gate or electrolyte functionalized with corresponding oxidase enzyme (e.g., glucose oxidase). Enzyme reaction produces Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, which is detected. | High sensitivity and low detection limits achieved [5]. |

| Dopamine [5] | PEDOT:PSS | Gate functionalization; direct oxidation of dopamine at the gate alters effective V_G. | Capable of real-time monitoring in physiological fluids [5]. |

| DNA, Proteins [5] | PEDOT:PSS | Gate or channel functionalized with aptamers or antibodies. Binding events induce potential or capacitance changes. | High specificity for biomarker detection [5]. |

OECT Biosensing Mechanisms

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for OECT Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS Dispersion | Benchmark p-type OMIEC; forms the conductive channel. | Sigma-Aldrich Orgacon ICP 1050; often requires additives [23] [20]. |

| (3-glycidyloxypropyl)trimethoxysilane (GOPS) | Cross-linker; renders PEDOT:PSS films insoluble in aqueous electrolytes. | Critical for stable operation in water [23] [20]. |

| Ethylene Glycol (EG) | Secondary dopant; enhances the electronic conductivity of PEDOT:PSS films. | Can increase conductivity by nearly two orders of magnitude [20]. |

| Dodecylbenzenesulfonic Acid (DBSA) | Dopant and surfactant; improves conductivity and film formation for PANI and PEDOT:PSS. | Used to process PANI into organic solvents [20]. |

| Polyaniline (PANI) | Alternative p-type OMIEC; lower cost but also lower performance than PEDOT:PSS. | Requires doping with acids like DBSA or CSA for solubility and conductivity [20]. |

| Ag/AgCl Gate Electrode | Non-polarizable gate; provides a stable reference potential, allowing for smaller gate designs. | Preferred over polarizable gates (Pt, Au) for integrated sensors [5]. |

| Gel Electrolytes | Solid-state electrolyte; prevents leakage, enables flexible/wearable devices. | Includes hydrogels (e.g., PVA) and ionic liquid gels (e.g., [Câ‚‚MIM][EtSOâ‚„]) [16]. |

| Propioxatin A | Propioxatin A, MF:C17H29N3O6, MW:371.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Hrk BH3 | Hrk BH3, MF:C99H160N30O31, MW:2266.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

PEDOT:PSS remains the cornerstone OMIEC for OECTs due to its excellent conductivity, ease of processing, and well-understood properties. However, as research advances, materials like melanin blends show promise for enhancing sustainability and performance, while novel n-type polymers like PBTI2g-DTCN are unlocking complementary circuits and low-power devices [18] [22]. The future of OMIEC development lies in creating tailored materials that offer not only high µC* products but also improved stability, specificity, and integration with solid-state electrolytes for robust, flexible, and implantable bioelectronic sensors. The combination of material innovation, precise fabrication protocols, and creative functionalization strategies will continue to expand the sensitive and powerful biosensing capabilities of OECTs.

Organic Electrochemical Transistors (OECTs) have emerged as a prominent platform in the field of bioelectronics, particularly for biosensing applications. Their significance stems from an efficient architecture that separates the gate electrode from the transistor device, enabling high-sensitivity detection of biological events [3]. OECTs operate at low voltages (typically below 1 V), exhibit high transconductance (gm), and possess inherent biocompatibility, making them exceptionally suitable for interfacing with biological systems [5] [3]. The core of an OECT's function lies in its use of an organic mixed ionic-electronic conductor (OMIEC) as the channel material, which facilitates the transduction of biological signals into amplified electrical readouts through electrochemical processes [5] [13]. This document delineates the fundamental mechanisms behind this transduction and provides detailed protocols for their experimental implementation, framed within the context of advanced biosensing research.

Fundamental Working Principles of OECTs

Device Structure and Configuration

A typical OECT is a three-terminal device consisting of source, drain, and gate electrodes [5] [13]. The source and drain electrodes are connected by a channel made from an OMIEC, such as the commonly used poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrene sulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) [5] [13]. This channel is in direct contact with an electrolyte, which also contains the gate electrode. This configuration is a key differentiator from traditional organic field-effect transistors (OFETs), as the electrolyte replaces the insulating dielectric layer, allowing for direct ionic modulation of the channel's conductivity [3]. The gate electrode can be made from polarizable materials (e.g., Au, Pt) or non-polarizable materials (e.g., Ag/AgCl), with the latter often preferred for integrated devices as it avoids the need for an oversized gate [5].

Operational Mechanism and Transconductance

The operation of an OECT is governed by the electrochemical doping and de-doping of the channel material by ions from the electrolyte [3]. When a gate voltage (VG) is applied, it drives ions to move between the electrolyte and the OMIEC channel. For a p-type OECT like one based on PEDOT:PSS, applying a positive VG causes cations from the electrolyte to inject into the channel. This influx of cations electrochemically reduces the PEDOT chain (de-doping), decreasing the hole density and thus reducing the drain current (ID) [5] [16]. The relationship is described by the Bernards model, which treats the OECT as two coupled circuits: an ionic circuit (ions moving in the electrolyte) and an electronic circuit (holes or electrons moving in the channel) [5] [3].

The efficiency of an OECT in converting a small gate voltage change into a large current signal is quantified by its transconductance, gm = ∂ID/∂VG [5] [13]. This parameter is crucial for biosensing, as it directly correlates with the device's signal amplification capability and sensitivity. The maximum transconductance can be expressed as: [ gm = \frac{W d}{L} \mu C^* |V{G} - V_{T}| ] where W, d, and L are the channel width, thickness, and length, respectively; μ is the charge carrier mobility; C* is the volumetric capacitance of the channel material; and VT is the threshold voltage [5] [13]. Consequently, high-performance OECTs can be engineered by optimizing the device geometry and the OMIEC's electronic properties [16].

Core Biosensing Mechanisms and Functionalization Strategies

The exceptional sensitivity of OECTs to ionic and electrochemical changes in their environment is harnessed for biosensing through targeted functionalization. The primary sensing mechanisms can be classified into three categories, based on which component of the OECT is functionalized to interact with the target analyte.

Gate Functionalization

This is the most conventional and widely used strategy for developing OECT-based biosensors [5]. The gate electrode is modified with a biorecognition element (e.g., an enzyme, antibody, or aptamer) that is specific to the target analyte.

- Mechanism: When the target analyte interacts with the functionalized gate surface, it triggers a change in the gate's electrochemical properties. This can occur via:

- A redox reaction that generates or consumes electrons, altering the effective gate potential (VeffG) [5] [24]. For instance, the enzyme glucose oxidase catalyzes the oxidation of glucose, producing H2O2, which can be oxidized at the gate electrode, generating a current that modulates VG.

- A capacitive change caused by the binding of charged biomolecules (e.g., DNA, proteins) to the gate surface, which alters the double-layer capacitance and thus VeffG [5].

- Signal Transduction: The change in VeffG is then amplified by the OECT, resulting in a measurable shift in the transfer curve (ID vs. VG) or a change in the drain current at a fixed bias [5]. This mechanism is highly effective for detecting a wide range of targets, from small molecules like glucose and dopamine to macromolecules like DNA and proteins [5] [13].

Channel-Electrolyte Interface Functionalization

In this approach, the surface or bulk of the OMIEC channel is functionalized to be responsive to the target analyte.

- Mechanism: The analyte interacts directly with the channel material, leading to a change in the channel's electronic structure or a voltage drop at the electrolyte/channel interface [5]. This interaction can modulate the channel's conductivity directly, without necessarily involving the gate electrode.

- Signal Transduction: The binding or reaction event alters the doping level or charge carrier mobility within the channel, leading to a direct change in the drain current (ID) [5] [13]. This method is often used for sensing ions or pH, where the channel material itself can be designed to be selectively responsive.

Electrolyte Functionalization

The electrolyte itself can be turned into a sensing component by incorporating elements that react with the target.

- Mechanism: Enzymes, ion-selective membranes, or even suspended cells are integrated into the electrolyte [5]. The primary reaction with the analyte occurs within the electrolyte bulk. For example, an enzyme like lactate oxidase can be suspended in the electrolyte to catalyze the breakdown of lactate, producing a change in local ion concentration (e.g., H+).

- Signal Transduction: The products of the reaction (e.g., ions) modulate the ionic strength or composition of the electrolyte. This change affects the gating efficiency of the OECT, ultimately leading to a measurable change in ID [5] [13]. This approach is useful for creating broad-spectrum metabolite sensors.

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for developing and operating a functionalized OECT biosensor.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details essential materials and their functions for constructing and functionalizing OECT-based biosensors, as derived from recent literature.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for OECT Biosensor Fabrication

| Item Name | Function/Description | Key Application in OECT Biosensing |

|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS | Benchmark p-type OMIEC; high conductivity and biocompatibility [13]. | Standard channel material; can be chemically tuned for enhanced performance or specific sensing [5] [13]. |

| Gold (Au) Gate Electrodes | Polarizable electrode; easily functionalized with thiolated biomolecules [5]. | Platform for immobilizing enzymes, antibodies, or DNA probes for specific analyte recognition [5] [24]. |

| Ag/AgCl Gate Electrodes | Non-polarizable electrode with stable potential; enables smaller device footprints [5]. | Used as a stable reference, often in ion-sensing or when a constant gate potential is critical [5]. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Standard aqueous electrolyte with physiological pH and ion concentration. | Liquid electrolyte for in-vitro testing and characterization of OECT biosensor performance [13]. |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-based Hydrogels | Synthetic hydrogel electrolyte; tunable mechanical properties and ion conductivity [16]. | Solid-state electrolyte for wearable and implantable devices; reduces leakage and improves stability [16]. |

| Chitosan-based Hydrogels | Natural hydrogel derived from chitin; offers inherent biocompatibility [16]. | Biocompatible solid electrolyte for applications requiring close tissue integration [16]. |

| Glucose Oxidase (GOx) | Enzyme that catalyzes the oxidation of glucose to gluconolactone and H2O2 [5]. | Biorecognition element immobilized on the gate for OECT-based glucose biosensors [5] [24]. |

| Aptamers | Short, single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules that bind to a specific target. | Synthetic biorecognition elements for gate functionalization to detect proteins, ions, or small molecules [5]. |

| Valtropine | Valtropine, MF:C13H23NO2, MW:225.33 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Mesutoclax | Mesutoclax, CAS:2760536-87-4, MF:C45H50ClN7O8S, MW:884.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Quantitative Performance Metrics of OECT Biosensors

The performance of OECT biosensors is quantitatively evaluated using several key metrics, including sensitivity, limit of detection (LOD), and dynamic range. The following table summarizes reported performance for various targets, highlighting the efficacy of different sensing mechanisms.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of OECT Biosensors for Various Analytes

| Target Analyte | Sensing Mechanism | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Sensitivity | Key Material/Strategy | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | Gate Functionalization (GOx) | ~100 nM | High (μA/mM) | Au gate with enzyme/redox mediator | [5] |

| Dopamine (DA) | Gate Functionalization | ~10 nM | -- | Selective membrane/functionalized gate | [5] |

| Lactate (LA) | Gate Functionalization / Electrolyte Functionalization | -- | -- | Lactate oxidase enzyme | [5] |

| DNA | Gate Functionalization (Aptamer) | -- | -- | Capacitive change from target binding | [5] |

| Proteins (e.g., IgG) | Gate Functionalization (Antibody) | -- | -- | Binding-induced capacitive or potential shift | [5] |

| Ions (Na+, K+) | Channel Functionalization | -- | -- | Ion-selective channel or membrane | [5] [16] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: OECT-based Glucose Biosensing

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for fabricating and characterizing a gate-functionalized OECT for glucose detection, a canonical application in the field.

Device Fabrication

- Substrate Preparation: Clean a glass or flexible PET substrate sequentially with acetone, isopropanol, and deionized water in an ultrasonic bath for 10 minutes each. Dry under a stream of nitrogen.

- Electrode Patterning: Using photolithography or shadow masking, pattern and deposit a 5 nm Cr adhesion layer followed by a 50 nm Au layer to form the source and drain electrodes (channel length L = 10-100 µm, width W = 100-1000 µm).

- Channel Deposition: Spin-coat a commercially available PEDOT:PSS solution (e.g., Clevios PH 1000) onto the substrate at 2000 rpm for 60 seconds, covering the gap between the source and drain. Anneal on a hotplate at 120°C for 15 minutes to dry the film.

- Gate Electrode Fabrication: Pattern a separate Au gate electrode on a separate substrate or integrate it on the same chip.

Gate Functionalization

- Gate Cleaning: Clean the Au gate electrode via oxygen plasma treatment for 2 minutes.

- Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) Formation: Immerse the gate in a 1 mM solution of 6-mercapto-1-hexanol (MCH) in ethanol for 1 hour. This forms a SAM that passivates the surface and provides a base for enzyme attachment.

- Enzyme Immobilization: Incubate the SAM-modified gate with a solution containing 10 mg/mL Glucose Oxidase (GOx) and 5 mM 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) in a phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 2 hours at 4°C. EDC catalyzes the formation of amide bonds between carboxyl groups on the enzyme and the terminal hydroxyl groups of the MCH SAM.

- Rinsing and Storage: Rinse the functionalized gate thoroughly with phosphate buffer to remove unbound enzyme. Store in PBS at 4°C until use.

Electrical Characterization and Sensing

- Setup Assembly: Assemble the OECT in an electrochemical cell filled with PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.4) as the electrolyte. Connect the source, drain, and gate to a source measure unit (e.g., Keithley 2600B) or a potentiostat.

- Baseline Characterization: In the absence of glucose, measure the output characteristics (ID vs. VD at different VG) and transfer characteristics (ID vs. VG at a fixed VD, e.g., -0.1 V to -0.5 V). Calculate the transconductance (gm) from the transfer curve.

- Glucose Sensing:

- Apply a constant VD (e.g., -0.3 V) and a constant VG (e.g., 0.5 V for an Au gate).

- Monitor the drain current (ID) in real-time.

- Sequentially add small volumes of concentrated glucose stock solution to the electrolyte to achieve desired final concentrations (e.g., from 1 µM to 10 mM).

- Allow the current to stabilize after each addition.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the change in ID (ΔID) or normalized current change (ΔID/ID(initial)) as a function of glucose concentration.

- Fit the data to a suitable model (e.g., Michaelis-Menten kinetics for enzymatic sensors) to extract the sensitivity and LOD (typically calculated as 3× the standard deviation of the baseline noise divided by the sensitivity).

OECTs represent a versatile and powerful tool for transducing biological events into quantifiable electrical signals. Their core mechanisms—gate, channel, and electrolyte functionalization—leverage the interplay between ionic and electronic charges in OMIECs to provide highly sensitive and amplified biosensing capabilities. As research progresses, the integration of OECTs with advanced materials like gel electrolytes [16] and their incorporation into closed-loop systems such as implantable drug delivery platforms [24] promise to unlock new frontiers in personalized medicine, real-time health monitoring, and diagnostic technologies. The protocols and data outlined herein provide a foundational framework for researchers and scientists to advance this rapidly evolving field.

Fabrication and Functionalization: Methodologies for Diverse Biosensing Applications

The integration of organic electrochemical transistors (OECTs) into advanced biosensing platforms requires fabrication methodologies that support mechanical flexibility, biocompatibility, and scalable production. This document details application notes and protocols for leveraging flexible printed circuit board (fPCB) technology and customizable inkjet printing to create high-performance, scalable OECT biosensors. These techniques enable the development of wearable and implantable devices capable of precise biomarker detection for research and clinical applications, combining the mechanical advantages of fPCBs with the patterning precision of advanced printing techniques [5] [25] [26].

fPCB Technology for OECT Biosensing Platforms

Material Selection and Stack-Up Design

The foundation of a reliable OECT-fPCB platform lies in the appropriate selection of materials that ensure both electrical performance and mechanical durability.

- Substrate and Copper: Polyimide is the standard substrate material due to its excellent thermal stability (withstanding soldering temperatures up to 260°C), mechanical flexibility, and low dielectric constant (Dk ≈ 3.2 @ 1GHz), which reduces signal loss [27] [28] [29]. For the conductive layers, rolled annealed copper is preferred over electrodeposited copper for dynamic flexing applications, as it offers superior ductility and resistance to fatigue cracking during repeated bending [27] [28].

- Stack-Up Configuration: A typical 2-layer fPCB stack-up for an OECT biosensor might consist of a 25μm polyimide core, with 18μm rolled annealed copper layers on both sides, laminated using adhesives or adhesiveless processes. Adhesiveless laminates are recommended for enhanced reliability as they prevent delamination under mechanical stress [27] [28]. The stack-up must be designed to balance flexibility with the need for signal and ground planes for impedance control.

Table 1: fPCB Material Properties for OECT Integration

| Material/Property | Polyimide (Flex) | FR-4 (Rigid for Stiffeners) | Impact on OECT Biosensor Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dielectric Constant (Dk) @1GHz | ~3.2 [28] | ~4.5 [28] | Lower signal loss for high-frequency biosensing signals |

| Glass Transition Temp (Tg) | >250°C [28] | 130-180°C [28] | Withstands high-temperature processing and soldering |

| Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE) | 12-15 ppm/°C [28] | 14-18 ppm/°C [28] | Reduced warping and better compatibility with coated OMIECs |

| Moisture Absorption | 2.8% [28] | 0.8% [28] | Requires pre-bake before assembly to prevent outgassing |

Critical fPCB Layout and Routing Guidelines

OECT biosensors require meticulous layout to maintain integrity during both static integration and dynamic operation in wearable formats.

- Bend Radius Management: Violations of the minimum bend radius account for a majority of field failures in flexible circuits [28]. Adherence to IPC-2223 standards is critical. For a static bend (e.g., a one-time fit into a device housing), the minimum radius is typically 10x the total board thickness. For dynamic bends (e.g., in a joint monitor), the minimum radius should be 100-150x the thickness [28] [29]. For example, a 0.15mm thick single-layer flex should have a dynamic bend radius no smaller than 15mm.

- Trace Routing and Via Placement: Conductors in bend areas should be routed perpendicular to the bend axis to minimize stress [28]. Sharp 90° angles should be avoided in favor of curved traces [27] [29]. Plated through-hole (PTH) vias are rigid and must be kept out of bend zones; a minimum distance of 3x the board thickness from the bend line is recommended. Teardrop pads should be used at trace-to-via junctions to reduce stress concentration [27] [28].

- Neutral Axis Optimization: To prevent tensile or compressive forces on copper traces during bending, critical traces should be positioned near the mechanical neutral axis of the flex stack-up. This can be achieved through careful layer planning, placing thin signal traces between layers of polyimide [28].

- Stiffener Integration: Components like microcontrollers or passive components require rigid support. Stiffeners made of FR4 or polyimide should be laminated to the fPCB in areas with component placements, ensuring they do not impinge on designated flex zones [27] [29].

Table 2: fPCB Bend Radius Guidelines per IPC-2223

| Flex Layer Count | Total Thickness (mm) | Static Min Bend Radius | Dynamic Min Bend Radius |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Layer | 0.15 | 1.5mm (10:1 ratio) [28] | 15mm (100:1 ratio) [28] |

| Double Layer | 0.25 | 2.5mm (10:1 ratio) [28] | 37.5mm (150:1 ratio) [28] |

| Multi-Layer (4+) | 0.50 | 10mm (20:1 ratio) [28] | Not Recommended [28] |

Protocol: fPCB Design and Fabrication for a Wearable OECT Biosensor

Objective: To design and fabricate a 2-layer fPCB that serves as the substrate and interconnect for a dynamic flexing OECT-based lactate sensor integrated into athletic wear.

Materials:

- Polyimide substrate (25μm)

- Rolled annealed copper foil (18μm, 0.5 oz)

- Adhesiveless laminate material

- Polyimide-based coverlay (25μm)

- FR4 stiffener (0.2mm) for component areas

Procedure:

- Define Bend Requirements: Identify the specific area of the textile that will experience repeated bending during movement. Classify this as a dynamic flex zone.

- Calculate Minimum Bend Radius: Based on a 2-layer stack-up with an estimated final thickness of 0.2mm, the dynamic bend radius is calculated as 0.2mm x 150 = 30mm [28]. Incorporate a 20% safety margin, resulting in a design radius of 36mm.

- Stack-Up Design: Finalize a stack-up: Top Coverlay / Signal Layer 1 (Cu) / Polyimide Core / Signal Layer 2 (Cu) / Bottom Coverlay.

- CAD Layout: a. Component Placement: Place all integrated circuits (ICs) and connectors in rigid sections defined by FR4 stiffeners. b. Trace Routing: In the dynamic flex zone, route traces carrying signals from the OECT perpendicular to the bend axis. Use curved traces with a minimum radius of 0.5mm [29]. Maintain a trace/space of at least 4/4mil (0.1mm) [29]. c. Via and Pad Design: Do not place vias within 0.6mm (3 x 0.2mm) of the bend line. Apply teardrops to all pads connected to traces.

- Design Rule Check (DRC): Run a DRC using the manufacturer's specific constraints for flex circuits, verifying spacing, annular rings, and bend zone rules.

- Panelization and Fabrication: Panelize the design with adequate spacing (≥2mm) and submit the Gerber files to a manufacturer with IPC-6013 Class 3 certification for flexible circuits [28] [29].

Customizable Inkjet Printing for OECT Fabrication

High-Resolution Micro-Dispensing Technology

Inkjet printing has evolved into a powerful additive manufacturing technique for depositing functional materials in OECTs. Recent advancements in high-resolution micro-dispensing enable the monolithic integration of all OECT components with exceptional precision.

- Technology Overview: Modern micro-dispensing systems can handle a wide viscosity range of inks (10 - 10âµ cP) and offer femtoliter-volume control with micrometer-scale resolution [26]. This allows for the precise deposition of conductors, semiconductors, insulators, and even gel electrolytes directly onto flexible substrates, including the fPCBs described in Section 2.

- Performance Capabilities: This technique has been used to fabricate fully printed OECTs with record intrinsic gains of 330 V/V and OECT-based amplifier circuits with a gain-bandwidth product of 1 MHz, the highest reported for fully printed OECTs [26]. This performance is critical for amplifying weak biosignals in real-time.

Functional Inks for OECT Biosensors

The efficacy of inkjet-printed OECTs hinges on the formulation of functional inks.

- Channel Materials: The most common organic mixed ionic-electronic conductor (OMIEC) is PEDOT:PSS. Inks are formulated with additives like surfactants and secondary dopants (e.g., ethylene glycol) to optimize jetting stability, film formation, and ultimately, electrical conductivity and ion transport [5] [6].

- Gate Electrodes: For biosensing, non-polarizable gate electrodes such as Ag/AgCl are often preferred. Silver silver-chloride (Ag/AgCl) inks can be printed to create stable reference gates [5] [6]. Polarizable gates made from gold or platinum nanoparticle inks are also used.

- Electrolytes: Hydrogel-based inks can be formulated to create solid-state or quasi-solid-state electrolyte layers that are compatible with printing and suitable for wearable applications [12] [26].

Protocol: Inkjet Printing of an OECT for Glucose Sensing

Objective: To fabricate a gate-functionalized OECT for glucose detection on a polyimide fPCB substrate using inkjet printing.

Materials:

- Pre-fabricated fPCB with Au source/drain electrodes

- PEDOT:PSS ink formulation (with 5% ethylene glycol dopant)

- Ag/AgCl nanoparticle ink

- Glucose oxidase (GOx) enzyme solution

- Nafion ionomer solution

- Insulating dielectric ink

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Clean the fPCB substrate with oxygen plasma to ensure a hydrophilic surface for optimal ink adhesion.

- Print OECT Channel: a. Load the PEDOT:PSS ink into a piezoelectric printhead. b. Using a waveform optimized for the ink's viscosity and surface tension, print the OECT channel layer, defining a precise geometry (e.g., W=1000μm, L=100μm) between the pre-existing source and drain contacts on the fPCB. c. Thermally cure the film at 120°C for 15 minutes in a nitrogen environment.

- Print and Functionalize Gate Electrode: a. Print the Ag/AgCl gate electrode structure in a dedicated area on the fPCB. b. Cure the gate electrode at 80°C for 30 minutes. c. Gate Functionalization: Deposit a mixed ink containing GOx and Nafion directly onto the printed gate electrode. The Nafion acts as a permselective membrane. Air-dry the functionalization layer at room temperature.

- Define Electrolyte Cavity: Print a dam wall of insulating dielectric ink around the OECT channel and gate to contain the liquid electrolyte.

- Curing and Validation: Perform a final low-temperature cure (60°C for 1 hour) to stabilize all layers without damaging the biological component (GOx). Validate device performance by measuring transfer and output characteristics in a phosphate buffer solution.

Integrated Workflow and Biosensing Application

The synergy between fPCB technology and inkjet printing enables a seamless workflow for creating advanced biosensing systems. The following diagram illustrates the integrated fabrication and sensing process.

Diagram 1: Integrated fPCB and Inkjet Printing Workflow for OECT Biosensors. This diagram outlines the sequential process from fPCB substrate fabrication to OECT printing/functionalization and final biosensing operation.

Biosensing Mechanism and Experimental Protocol

The operational principle of the integrated biosensor relies on the modulation of the OECT's channel current by a biochemical reaction at the functionalized gate.

Biosensing Mechanism: In a typical glucose sensor, the mechanism follows a gate-functionalization approach [5] [6]:

- Glucose in the analyte solution diffuses to the functionalized gate electrode.

- The immobilized glucose oxidase (GOx) enzyme catalyzes the oxidation of glucose to gluconolactone, consuming oxygen and generating hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚).