Computational Models for Neurostimulation Optimization: From Neural Circuits to Personalized Therapies

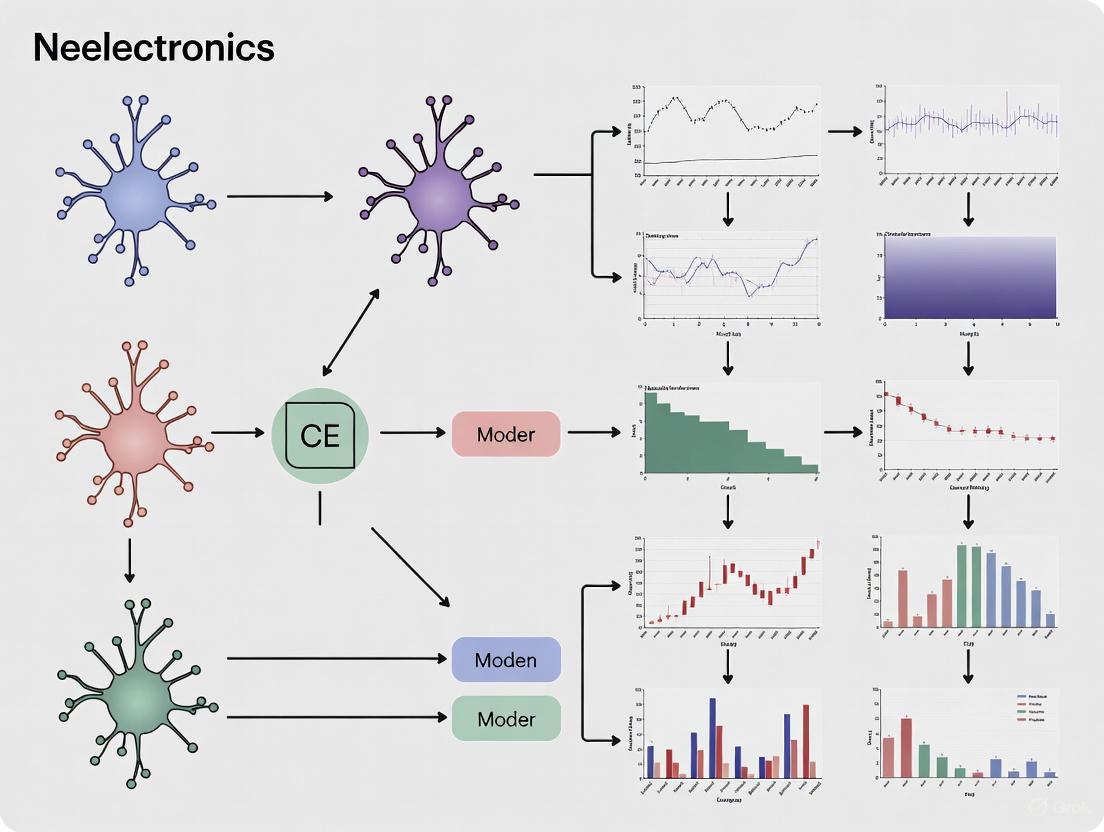

This article explores the transformative role of computational modeling in optimizing neurostimulation for brain disorders.

Computational Models for Neurostimulation Optimization: From Neural Circuits to Personalized Therapies

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of computational modeling in optimizing neurostimulation for brain disorders. It covers the foundational principles of how models bridge cellular-level processes with disease dynamics, details methodological advances from finite-element analysis to patient-specific virtual platforms, and addresses key challenges in troubleshooting and parameter optimization. A comparative analysis of classical and emerging neuromodulation techniques is provided, highlighting how in silico frameworks accelerate therapeutic discovery and enable closed-loop, AI-driven personalized neuromodulation strategies for conditions ranging from Parkinson's disease to disorders of attention.

Theoretical Foundations: How Computational Models Decode Neurostimulation Mechanisms

Understanding brain diseases requires integrating knowledge across spatial and temporal scales, from the biophysical properties of single neurons to the emergent dynamics of entire brain networks. Computational models are indispensable tools for bridging these scales, providing a framework to formalize hypotheses, incorporate diverse experimental data, and simulate the effects of interventions. A central challenge in the field is that modeling efforts have traditionally occurred in parallel: one class of models focuses on simulating neuronal dynamics (e.g., oscillations, excitability, and connectivity), while another focuses on the biological mechanisms of disease progression (e.g., protein spreading and glial responses) [1]. However, experimental evidence increasingly shows these processes are bidirectionally coupled. Neuronal activity can influence disease progression by, for example, accelerating the transneuronal transport of pathological proteins, while pathology feeds back to disrupt circuit function [1]. This application note outlines integrated computational approaches and detailed protocols to model these interactions, with a particular emphasis on applications in neurostimulation optimization for neurodegenerative diseases and neurological disorders.

Core Computational Frameworks and Their Applications

Modeling Neuronal Dynamics Across Scales

Computational models of neuronal activity during disease aim to simulate and explain functional changes observed via neuroimaging and electrophysiology. These models span from single neurons to whole-brain networks.

Table 1: Computational Models of Neuronal Dynamics in Neurodegeneration

| Model Scale | Core Mathematical Formulation | Key Parameters | Simulated Disease Phenomena | Representative Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Neuron [1] | ( C\frac{dVi}{dt} = -I{\mathrm{ion}}(Vi, gi) + \sumj w{ij}Sj(t) + I{\mathrm{ext}}(t) ) | Ion channel conductances (( gi )), synaptic weights (( w{ij} )), external drive (( I_{ext} )) | Altered excitability, firing patterns, hyperexcitability | Action potential trains, subthreshold oscillations |

| Neural Mass/Mean-Field [2] [3] | Population firing rate as a function of average membrane potential and input; Kuramoto oscillators for rhythm generation | Synaptic time constants, coupling strength between populations, input from pacemakers (e.g., medial septum) | Theta-gamma phase-amplitude coupling, oscillatory slowing (e.g., reduced alpha/increased theta), hypersynchrony | Local Field Potential (LFP), EEG/MEG spectra, functional connectivity graphs |

| Whole-Brain Network [1] | Coupled neural mass models with inter-regional connectivity defined by the connectome | Structural connectivity matrix, global coupling scaling, transmission delays | Altered functional connectivity (e.g., Default Mode Network disruption), network instability | fMRI BOLD signals, source-localized EEG/MEG dynamics |

Modeling Disease Progression Mechanisms

Beyond neuronal activity, generative models of core disease mechanisms are required to simulate pathology progression.

Table 2: Models of Neurodegenerative Disease Mechanisms

| Modeled Process | Typical Modeling Framework | Key Parameters & Variables | Linked Disease Biology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prion-like Protein Spreading [1] | Network diffusion models on the connectome; reaction-diffusion equations | Spreading rate, clearance rate, seed location, nodal vulnerability | Accumulation and interneuronal spread of tau, alpha-synuclein, amyloid-beta |

| Glial & Vascular Interactions [1] | Systems of differential equations | Neuroinflammatory signaling, metabolic support, blood flow regulation | Astrocyte dysfunction, microglial activation, neurovascular uncoupling |

| Glymphatic Clearance [1] | Computational fluid dynamics within perivascular spaces | Cerebrospinal fluid flow rate, perivascular space geometry, arterial pulsatility | Impaired clearance of protein waste products, particularly during sleep |

Integrated Frameworks: Bridging Dynamics and Pathology

The most advanced models seek to unify the frameworks described above by creating bidirectional feedback loops between neural activity and disease processes. In such integrated models, neuronal activity can modulate the release and clearance of pathological proteins, while the evolving pathological burden, in turn, alters ion channel function, synaptic efficacy, and cell survival, thereby shaping subsequent neural dynamics [1]. This creates a co-evolutionary process that can capture the progressive nature of neurodegeneration more realistically than unidirectional models.

Detailed Experimental & Simulation Protocols

Protocol 1: Simulating Pathological Theta-Gamma Oscillations and Neurostimulation in a Hippocampal Circuit

Application: This protocol is used to study how neurostimulation affects memory-related oscillations in conditions like Alzheimer's disease and to optimize stimulation parameters [3].

Workflow Diagram: Hippocampal Theta-Gamma Neurostimulation Model

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Model Construction:

- Medial Septum (Pacemaker): Implement a set of abstract Kuramoto oscillators to represent the medial septum. This component generates a dynamical theta rhythm (4-12 Hz) capable of phase reset, as opposed to a simple fixed-frequency input [3].

- Hippocampal Formation (Target): Build a network of biophysically realistic neurons (e.g., using Hodgkin-Huxley formalism) representing key hippocampal subregions. This network should include excitatory and inhibitory populations connected with conductance-based synapses [3].

- Coupling: Connect the Kuramoto oscillator (septal) output to the hippocampal network as an exogenous oscillatory drive.

Model Calibration & Pathological State Induction:

- Healthy Baseline: Adjust the strength of the septal theta drive and the internal synaptic weights within the hippocampal network until the model produces self-sustained theta-nested gamma oscillations, replicating a healthy state [3].

- Inducing Pathology: Weaken the septal theta input or introduce synaptic degradation (e.g., reduce NMDA receptor conductance) to move the network into a "pathological" state. This state is characterized by the absence or severe disruption of theta-gamma oscillations [3].

Neurostimulation Implementation:

- Stimulation Type: Define the stimulation protocol.

- Single-Pulse: A brief, high-amplitude pulse.

- Pulse-Train: A series of pulses delivered at a specific frequency (e.g., theta frequency) [3].

- Stimulation Parameters: Set the amplitude, pulse width, and timing of the stimulation. For closed-loop protocols, define the trigger, such as a specific phase of the ongoing (albeit weak) theta rhythm.

- Stimulation Type: Define the stimulation protocol.

Simulation and Data Analysis:

- Run the simulation and record the local field potential (LFP) and spiking activity from the hippocampal network.

- Quantitative Analysis: Calculate the power spectral density of the LFP to identify dominant rhythms. Use metrics like phase-amplitude coupling (PAC) to quantify the interaction between theta and gamma rhythms. Determine if stimulation successfully restores physiological oscillatory dynamics [3].

Protocol 2: Optimizing Peripheral Nerve Stimulation Using a Surrogate Fiber Model

Application: This protocol accelerates the design and optimization of precise neuromodulation protocols for the vagus nerve (e.g., for epilepsy, depression) and other peripheral nerves (e.g., for chronic pain) [4].

Workflow Diagram: Peripheral Nerve Stimulation Optimization

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Define the Anatomical and Electrical Model:

- Nerve Anatomy: Create a finite element method (FEM) model of the target nerve (e.g., human or pig vagus nerve) including its geometry, fascicles, and surrounding tissue [4].

- Electrode Configuration: Incorporate the geometry and position of the stimulating cuff electrode (e.g., ImThera 6-contact or LivaNova helical cuff) into the FEM model [4].

- Generate Training Data: Use the FEM model to compute the distribution of electric potential within the nerve for a wide range of stimulation parameters (waveform shape, amplitude, pulse width, active contact). Apply these potentials as boundary conditions to a high-fidelity, biophysical nerve fiber model (e.g., the McIntyre-Richardson-Grill (MRG) model in NEURON) to generate a comprehensive dataset of spatiotemporal fiber responses [4].

Develop and Train the Surrogate Model (S-MF):

- Model Architecture: Implement a simplified cable model of a myelinated nerve fiber with trainable parameters. The model should capture the essential nonlinearities of the MRG model but be designed for execution on a GPU [4].

- Training: Use the dataset from Step 1 to train the surrogate model via backpropagation and gradient descent. The goal is for the S-MF to accurately predict the MRG model's responses (e.g., activation threshold, spiking activity) to arbitrary stimulation waveforms [4].

Optimization and Validation:

- Define Objective: State the optimization goal clearly. For example, "activate Fiber Group A while avoiding activation of Fiber Group B within the same nerve."

- Run Optimization: Use the trained S-MF with gradient-based or gradient-free optimization algorithms to search the parameter space (waveform shape, amplitude, contact configuration) for the set that best meets the objective. The computational efficiency of S-MF (providing >2,000x speedup) makes large-scale optimization feasible [4].

- Validate: Test the optimized parameters by running them in the original high-fidelity NEURON model to confirm the predicted outcome [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Resources

| Tool/Resource Name | Type/Function | Key Application in Multi-Scale Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| NEURON [4] | Environment for detailed single neuron and network simulation | Gold-standard for simulating biophysical neuron models (e.g., MRG fiber); supports extracellular stimulation. |

| Mean-Field / Neural Mass Models [2] [1] | Mathematical framework simulating average activity of neuronal populations | Efficiently simulates EEG/MEG signals and large-scale network dynamics; can be incorporated into whole-brain models. |

| Finite Element Method (FEM) [4] | Numerical technique for solving physical field problems | Calculates the distribution of electric potential in neural tissue during electrical stimulation, crucial for dosing. |

| Kuramoto Oscillators [3] | Mathematical model for describing synchronization in coupled oscillators | Represents pacemaker nuclei (e.g., medial septum) to generate dynamical brain rhythms with phase reset capabilities. |

| AxonML / S-MF Model [4] | GPU-accelerated surrogate model of nerve fibers | Enables rapid, large-scale parameter sweeps and optimization of neurostimulation protocols orders of magnitude faster than NEURON. |

| Patient-Specific Connectomes [5] | Structural connectivity maps of an individual's brain, derived from diffusion MRI | Informs whole-brain network models and prion-like spreading models, allowing for personalized prediction of disease progression and stimulation effects. |

| Duocarmycin SA intermediate-1 | Duocarmycin SA intermediate-1, MF:C30H35IN2O8, MW:678.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2,5-Dimethylpyrazine-d3 | 2,5-Dimethylpyrazine-d3, MF:C6H8N2, MW:111.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The path to effective neurostimulation therapies for brain diseases lies in embracing the multi-scale, bidirectional complexity of the brain. The integrated computational frameworks and detailed protocols outlined here provide a roadmap for researchers to build models that not only replicate pathological phenotypes but also reveal the mechanistic interplay between neuronal dynamics and disease biology. By leveraging these approaches—from hybrid oscillatory models to highly efficient surrogate fibers—the field can accelerate the rational design of patient-specific neurostimulation protocols that are capable of both restoring function and altering the course of disease progression.

The "informational lesion" concept represents a paradigm shift in understanding deep brain stimulation (DBS), moving beyond simplistic excitation/inhibition models toward a circuit-based framework where high-frequency stimulation masks or disrupts the flow of pathological neural information. This Application Note synthesizes recent advances in DBS mechanisms, focusing on the implications for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and Parkinson's disease (PD), and provides detailed experimental protocols for investigating these mechanisms. By integrating electrophysiological recordings, computational modeling, and genetically-encoded sensors, researchers can systematically decode how DBS creates informational lesions through differential synaptic depression, antidromic blocking, and network modulation. The protocols outlined herein enable quantitative assessment of presynaptic and postsynaptic dynamics during DBS, facilitating the development of optimized neuromodulation therapies for neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Traditional theories of DBS mechanism oscillated between net excitation and inhibition of neural elements. The "functional lesion" hypothesis suggested DBS inhibits pathological neural activity, similar to ablative procedures but reversibly. This framework has been progressively supplanted by the informational lesion paradigm, which posits that DBS primarily disrupts the transmission of pathological neural signals rather than simply inhibiting or exciting the stimulated nucleus [6] [7].

The informational lesion hypothesis provides a more nuanced explanation for DBS effects, suggesting that high-frequency stimulation prevents neurons from responding to intrinsic oscillations and disrupts pathological network patterns through multiple mechanisms:

- Antidromic blocking: DBS may activate axons antidromically, preventing orthodromic transmission of pathological signals [6]

- Synaptic depression: High-frequency stimulation causes depletion of neurotransmitter release, differentially affecting glutamatergic and GABAergic synapses [8]

- Network resetting: DBS imposes a new, regularized activity pattern that overrides pathological oscillations [6] [9]

This paradigm shift is particularly relevant for psychiatric disorders like OCD, where DBS is thought to disrupt pathological overactivity in cortico-striatal-thalamo-cortical (CSTC) circuits [6]. The informational lesion framework also aligns with the temporal profile of DBS effects in OCD, where immediate improvements in mood and anxiety are followed by more gradual reduction in obsessive-compulsive symptoms, suggesting both immediate neuromodulation and long-term synaptic remodeling [6].

Table 1: Evolution of DBS Mechanism Theories

| Theory | Proposed Mechanism | Key Evidence | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Lesion | Inhibition of pathological neural activity | Similar effects to ablation; reduced STN output in PD [8] | Cannot explain activation effects; oversimplified |

| Excitation/Inhibition | Net excitation or inhibition of neural elements | Cellular responses to electrical stimulation | Overly simplistic; fails to explain network effects |

| Informational Lesion | Disruption of pathological signal transmission | Antidromic blocking; synaptic depression; network modulation [6] [8] | Complex to measure; multiple simultaneous mechanisms |

| Circuit Modulation | Restoration of natural dynamic communication across brain circuits | Normalization of CSTC hyperactivity in OCD [6] | Circuit interactions not fully characterized |

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Neurophysiological Effects of DBS Across Disorders

Table 2: DBS Outcomes Across Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders

| Disorder | Primary DBS Target | Clinical Efficacy | Cognitive Effects | Mechanistic Insights |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parkinson's Disease | STN, GPi | Significant motor improvement [7] | Verbal fluency decline; executive function variably affected [7] | Differential synaptic depression; inhibited STN neurons with activated afferents [8] |

| Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder | Ventral ALIC, NAcc, STN | ~60% response rate; FDA approved under HDE [6] | Cognitively safe; variable across domains [7] | Disruption of pathological CSTC circuit activity [6] |

| Treatment-Resistant Depression | Subcallosal cingulate, MFB | Antidepressant effects, especially MFB target [7] | No decline up to 18 months; mild improvement in memory/attention [7] | Restoration of normative network dynamics |

| Essential Tremor | VIM thalamus | Significant tremor reduction [7] | Occasional verbal fluency decline; other domains largely unaffected [7] | Modulation of cerebello-thalamo-cortical pathways |

| Dystonia | GPi | Significant symptom improvement [7] | Possible decline in processing speed [7] | Suppression of low-frequency (4-12 Hz) GPi oscillations |

Electrophysiological Signatures of Informational Lesions

Table 3: Electrophysiological Markers for DBS Optimization

| Parameter | Measurement Technique | Pathological Signature | DBS Normalization Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beta Oscillations (13-30 Hz) | STN LFP recordings [9] | Elevated beta power in PD [9] | Beta power reduction correlates with motor improvement [9] |

| Low-Frequency Oscillations (4-12 Hz) | GPi LFP recordings [9] | Elevated in dystonia [9] | Suppression correlates with symptom improvement [9] |

| Cortico-Striatal Connectivity | fMRI, EEG/MEG [6] | Overconnectivity in OCD [6] | Reduction correlates with OCD symptom relief [6] |

| Glutamate Release | Fiber photometry with iGluSnFR [8] | Not specified | Profound, intensity-dependent inhibition during DBS [8] |

| GABA Release | Fiber photometry with iGABASnFR [8] | Not specified | Inhibition during DBS, but less than glutamate [8] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Presynaptic and Postsynaptic Dynamics During DBS

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate how DBS differentially affects presynaptic terminal activity versus postsynaptic neuronal activity in target structures.

Background: The informational lesion effect arises from contrasting presynaptic and postsynaptic dynamics. Recent findings show DBS activates afferent axon terminals while inhibiting local neuronal somata, with differential depression of glutamatergic versus GABAergic neurotransmission [8].

Materials:

- Stereotactic surgical apparatus

- Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) for targeted expression of genetically-encoded indicators

- Hybrid electrode-optical fiber probes for simultaneous stimulation and photometry

- Spectrally-resolved fiber photometry system

- Programmable DBS pulse generator

Methods:

Surgical Preparation and Viral Expression

- Inject AAV9-syn-jGCaMP8f-WPRE into afferent source regions (e.g., M1 cortex for glutamatergic afferents to STN; GPe for GABAergic afferents)

- Inject AAV9-hSyn-DIO-tdTomato into target nucleus (e.g., STN) as fluorescence control

- Allow 3-4 weeks for viral expression and tracer transport

Hybrid Probe Implantation

- Implant custom electrode-optical fiber hybrid probe into target nucleus (e.g., STN)

- Ensure optical fiber tip is placed 0.1-0.2 mm above stimulating electrode tip

- Secure probe with dental acrylic and allow 1-2 weeks recovery

Spectrally-Resolved Fiber Photometry During DBS

- Record baseline fluorescence spectra for 5 minutes pre-stimulation

- Apply DBS using common clinical parameters (130 Hz, 60-μs pulse width, cathodic stimulation)

- Systematically vary stimulation intensity (100, 150, 200 μA) with washout periods between

- Continuously record time-lapsed fluorescence emission spectra throughout stimulation and recovery periods

- Calculate ratio of activity indicator fluorescence (FGCaMP) to control fluorescence (FtdTomato) to control for motion artifacts

Data Analysis

- Compute percent change in F_GCaMP/tdTomato ratio during stimulation versus baseline

- Compare magnitude of effects across stimulation intensities

- Statistically compare presynaptic versus postsynaptic responses

Expected Results: DBS produces sustained activation of presynaptic terminals (increased FGCaMP8f/tdTomato) but inhibition of postsynaptic neuronal activity (decreased FGCaMP6f/tdTomato), with both effects showing intensity-dependence [8].

Protocol 2: Measuring Neurotransmitter-Specific Synaptic Depression

Objective: To quantify DBS-induced changes in glutamate and GABA release in the stimulated nucleus.

Background: The informational lesion effect may involve differential synaptic depression, with greater decrease in glutamate release than GABA release, shifting excitation/inhibition balance toward inhibition [8].

Materials:

- AAV1-hSyn-FLEX-SF-Venus-iGluSnFR.S72A (glutamate sensor)

- AAV1-hSyn-FLEX-iGABASnFR.F102G (GABA sensor)

- AAV9-hSyn-DIO-tdTomato (fluorescence control)

- Hybrid electrode-optical fiber probes

- Spectrally-resolved fiber photometry system

Methods:

Sensor Expression

- Inject AAV1-hSyn-FLEX-SF-Venus-iGluSnFR.S72A and AAV9-hSyn-DIO-tdTomato into target nucleus (e.g., STN) of Vglut2-cre mice for glutamate measurements

- In separate cohort, inject AAV1-hSyn-FLEX-iGABASnFR.F102G and AAV9-hSyn-DIO-tdTomato for GABA measurements

- Allow 3-4 weeks for viral expression

Probe Implantation and Photometry

- Implant hybrid electrode-optical fiber probe into target nucleus

- Record baseline neurotransmitter sensor fluorescence (FVenus-iGluSnFR or FiGABASnFR) and control fluorescence (F_tdTomato)

- Apply DBS at varying intensities (100, 150, 200 μA) with standard parameters

- Continuously monitor fluorescence ratios during stimulation

Quantitative Analysis

- Calculate percent change in F_sensor/tdTomato ratio during DBS

- Compare magnitude of glutamate versus GABA release inhibition

- Determine intensity-dependence of synaptic depression

Expected Results: DBS causes profound, intensity-dependent inhibition of both glutamate and GABA release, with significantly greater depression of glutamatergic transmission, shifting excitation/inhibition balance toward inhibition [8].

Protocol 3: Mapping Circuit-Level Effects of Informational Lesions

Objective: To characterize how DBS creates informational lesions by modulating pathological network activity across distributed brain circuits.

Background: In OCD, DBS is thought to disrupt pathological overactivity in CSTC circuits [6]. Simultaneous electrophysiological recordings across multiple nodes can reveal how DBS creates informational lesions by normalizing network dynamics.

Materials:

- Multi-channel electrophysiology system

- Multi-site electrode arrays or simultaneous EEG/MEG-LFP setups

- Computational tools for connectivity analysis

Methods:

Multi-Site Recording Preparation

- Implant recording electrodes in key nodes of target circuit (e.g., for OCD: OFC, striatum, thalamus; for PD: STN, GPi, cortex)

- For non-invasive components, use high-density EEG or MEG co-registered with structural MRI

- Ensure precise temporal synchronization across all recording modalities

Network Activity Characterization

- Record baseline neural activity across nodes during rest and relevant behavioral tasks

- For OCD studies: measure CSTC circuit activity during symptom provocation

- For PD studies: measure beta oscillations during rest and movement

DBS Application and Network Monitoring

- Apply therapeutic DBS to target nucleus (e.g., ventral ALIC for OCD, STN for PD)

- Simultaneously record network activity across all nodes during stimulation

- Systematically vary DBS parameters (frequency, intensity, pulse width)

Connectivity and Information Flow Analysis

- Compute functional connectivity metrics (coherence, phase-locking value) between nodes

- Measure directionality of information flow (Granger causality, directed transfer function)

- Quantify changes in pathological oscillations (e.g., beta power in PD)

- Assess normalization of network dynamics relative to clinical improvement

Expected Results: Effective DBS normalizes pathological network activity by reducing overconnectivity in hyperactive circuits (e.g., CSTC in OCD), suppressing pathological oscillations (e.g., beta in PD), and restoring more natural information flow patterns [6] [9].

Visualization of Mechanisms and Methodologies

Informational Lesion Mechanisms in DBS

Experimental Workflow for DBS Mechanism Investigation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for DBS Mechanism Investigations

| Reagent / Tool | Specifications | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetically-Encoded Calcium Indicators | AAV9-syn-jGCaMP8f-WPRE; AAV9-hSyn-DIO-GCaMP6f-WPRE | Monitoring neural activity in specific cell populations | High sensitivity; cell-type specific expression; compatible with fiber photometry |

| Neurotransmitter Release Sensors | AAV1-hSyn-FLEX-SF-Venus-iGluSnFR.S72A (glutamate); AAV1-hSyn-FLEX-iGABASnFR.F102G (GABA) | Real-time measurement of neurotransmitter release | Specific to neurotransmitter type; high temporal resolution |

| Fluorescence Control Reporters | AAV9-hSyn-DIO-tdTomato | Control for motion artifacts and non-specific effects | Spectrally distinct from activity sensors; enables ratio-metric measurements |

| Hybrid Stimulation-Recording Probes | Custom electrode-optical fiber assemblies | Simultaneous DBS delivery and optical monitoring | Precise co-localization of stimulation and recording sites; minimal artifact |

| Computational Modeling Platforms | o2S2PARC; Sim4Life.web [10] | In silico testing of DBS parameters and mechanisms | Cloud-native; integrates EM modeling with neuronal dynamics; regulatory-grade |

| Personalized Optimization Algorithms | Bayesian Optimization (pBO) frameworks [11] | Individualized DBS parameter selection | Accounts for anatomical and functional individual differences; efficient parameter space exploration |

| Gamma-6Z-Dodecenolactone-d2 | Gamma-6Z-Dodecenolactone-d2, MF:C12H20O2, MW:198.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Fmoc-Gly-Gly-allyl propionate | Fmoc-Gly-Gly-allyl propionate, MF:C25H26N2O7, MW:466.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The informational lesion paradigm represents a fundamental shift in understanding DBS mechanisms, emphasizing disruption of pathological information flow rather than simple inhibition or excitation. The experimental protocols outlined herein enable researchers to quantitatively investigate these mechanisms across spatial scales - from synaptic-level neurotransmitter dynamics to circuit-level network interactions. As the field advances, computational models that integrate these multi-scale effects will be essential for developing truly personalized DBS therapies that optimize informational lesion creation while minimizing side effects. Future research should focus on closed-loop DBS systems that dynamically adjust stimulation parameters based on real-time biomarkers of pathological information flow, ultimately creating more effective and efficient neuromodulation therapies for neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Mechanistic Modeling for Target Identification in Parkinson's, Epilepsy, and Migraine

The development of effective therapies for complex neurological disorders is often hampered by the intricate and multifactorial nature of their underlying pathophysiology. For Parkinson's disease, epilepsy, and migraine, the precise neural mechanisms triggering symptoms remain incompletely understood, creating a critical bottleneck in therapeutic development. Within this context, computational modeling has emerged as a transformative tool, providing a virtual platform to dissect disease mechanisms, identify critical therapeutic targets, and optimize intervention strategies. These models serve as in-silico testbeds that tame biological complexity, from molecular interactions to large-scale neural network dynamics, offering a principled path toward personalized neuromodulation therapies. This article details specific application notes and experimental protocols for employing mechanistic models in target discovery across these three neurological conditions, framed within a broader research agenda on computational neurostimulation optimization.

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Parkinson's Disease: Targeting Basal Ganglia Circuit Dynamics and α-Synuclein Homeostasis

Parkinson's disease (PD) is characterized by the progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons and the pathological accumulation of α-synuclein (αsyn) protein. Computational models provide key insights into both the circuit-level and molecular-level dysfunction driving the disease.

Table 1: Key Computational Insights and Targets in Parkinson's Disease

| Modeling Level | Key Insight | Identified Target/Mechanism | Therapeutic Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circuit Dynamics | Excessive beta-band oscillations arise from cortex-STN-GPe resonance [12] [13] | Cortico-subthalamic hyperdirect pathway; STN-GPe loop | Targets for deep brain stimulation (DBS) to disrupt pathological oscillations [12] [14] |

| Dopamine Signaling | Loss of phasic, not tonic, dopamine drives early motor deficits [12] | Phasic dopamine signaling and its signal-to-noise ratio | Strategies to restore patterned, rather than continuous, dopamine signaling |

| Protein Homeostasis | Positive feedback loops between αsyn aggregation and degraded clearance [15] | Autophagy-lysosome pathway (ALP); Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway (UPP) | Small molecule inhibitors of aggregation; enhancers of ALP/UPP activity [15] |

Protocol 1: Developing a Model of α-Synuclein Homeostasis

- Objective: To build a mechanistic model that simulates the interplay between αsyn aggregation and cellular degradation pathways to identify critical control points for intervention.

- Background: The pathological aggregation of αsyn and the impairment of its clearance mechanisms are central to PD. Kinetic models integrate processes like nucleation, elongation, and fragmentation of αsyn aggregates with degradation pathways such as the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and autophagy-lysosome pathway (ALP) [15].

- Methodology:

- Model Formulation: Use a system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) to represent the concentrations of different αsyn species (monomer, oligomer, protofibril, fibril). Key reactions include primary nucleation ($v{nuc}$), elongation ($v{elong}$), and fragmentation ($v_{frag}$) [15].

- Incorporate Degradation: Introduce terms for the degradation of each αsyn species via UPS ($v{UPS}$) and ALP ($v{ALP}$). Model the known inhibitory effects of oligomers on proteasomal activity and of fibrils on ALP flux [15].

- Parameter Estimation: Calibrate model parameters (e.g., rate constants) against in vitro kinetic data of αsyn aggregation and clearance from the literature.

- Therapeutic Simulation: Simulate interventions such as: (a) introducing an aggregation inhibitor (reducing $v{elong}$), (b) enhancing ALP activity (increasing $v{ALP}$), and (c) combined strategies. Analyze the effect on steady-state levels of toxic oligomeric species.

- Expected Outcome: The model will identify which intervention, or combination thereof, most effectively reduces the burden of toxic αsyn species, providing a ranked list of promising therapeutic targets.

Diagram 1: α-synuclein aggregation and clearance pathways with intervention points.

Epilepsy: Identifying Seizure Onset and Suppression Targets

In epilepsy, particularly medically refractory forms, computational models help pinpoint the origins of hypersynchrony and guide the development of targeted neurostimulation protocols for seizure suppression.

Table 2: Computational Approaches for Seizure Identification and Control in Epilepsy

| Modeling Approach | Primary Application | Identified Target/Mechanism | Therapeutic Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large-Scale Network Models | Understand hyperexcitability from cell death and altered connectivity [16] | "Hub" neurons with aberrant high connectivity [16] | Focal ablation or silencing of hyper-connected hub cells |

| System Identification (SI) & Control | Reconstruct and mitigate seizures from real patient data [17] | State-space models derived from interictal/ictal EEG/LFP | Customized electrical stimuli for seizure suppression [17] |

| Mean-Field Neural Mass Models | Simulate macroscopic seizure dynamics and bifurcations [18] | Key parameters controlling transition to seizure (e.g., excitatory gain) | Open-loop or closed-loop DBS parameter optimization |

Protocol 2: Data-Driven Seizure Suppression via System Identification and Control

- Objective: To construct a patient-specific model from electrophysiological recordings and design a control input to suppress epileptiform activity.

- Background: System identification (SI) techniques can translate real brain signals (e.g., local field potentials) into mathematical models. These models can be used to design controllers that compute electrical stimuli to drive the brain state from a seizure (ictal) to a non-seizure (interictal) condition [17].

- Methodology:

- Data Acquisition & Preprocessing: Obtain intracranial EEG (iEEG) or local field potential (LFP) recordings from patients, containing both ictal and interictal segments. Filter the data to remove artifacts.

- Model Identification: Fit an Autoregressive (AR) model to the preprocessed signal. The order of the model is determined using criteria like Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). The AR model, which predicts the current signal value based on its past values, is given by: $y(t) = a1 y(t-1) + a2 y(t-2) + ... + ap y(t-p) + e(t)$ where $y(t)$ is the signal, $ai$ are the model coefficients, $p$ is the model order, and $e(t)$ is the error term [17].

- State-Space Conversion: Convert the identified AR model into a state-space representation. This format is essential for control theory applications and allows for the design of observers and controllers.

- Controller Design: Design a state-feedback controller (e.g., a linear-quadratic regulator - LQR). The controller calculates an optimal electrical stimulus $u(t)$ based on the estimated state of the system $x(t)$ to minimize a cost function that penalizes both seizure activity and control effort [17].

- In-Silico Validation: Simulate the closed-loop system (plant + observer + controller) to verify its efficacy in suppressing the simulated epileptiform activity before moving to pre-clinical or clinical testing.

- Expected Outcome: A patient-specific state-space model and an associated control law that can be implemented in a closed-loop neurostimulation device to deliver personalized seizure suppression therapy.

Diagram 2: Workflow for data-driven seizure model identification and control.

Migraine: Uncovering Genetic and Molecular Targets

Migraine is a complex disorder with a strong genetic component. Modern computational approaches integrate large-scale genomic data to pinpoint causal genes and pathways, offering new avenues for drug discovery and repurposing.

Table 3: Multi-Omics Insights for Target Identification in Migraine

| Computational Method | Data Input | Key Finding | Implication for Target Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning (ML) on snRNA-seq | snRNA-seq from 43 brain regions; GWAS data [19] | Enrichment in PoN_MG thalamus; calcium signaling pathway (Gene Program 1) | ARID3A transcription factor and calcium-related genes as regulators [19] |

| Integrated GWAS-eQTL-PheWAS | GWAS summary stats; multi-tissue eQTLs; PheWAS [20] | 31 blood and 20 brain migraine-associated genes; 13 druggable genes | Prioritized targets: NR1D1, THRA, NCOR2, CHD4 for drug development [20] |

| Meta-Learning for CGRP Inhibition | Chemical compounds from ChEMBL [21] | High-accuracy prediction of CGRP-inhibiting compounds (MetaCGRP model) | Accelerates screening of natural products and small molecules for migraine [21] |

Protocol 3: An Integrated Multi-Omics Pipeline for Migraine Target Prioritization

- Objective: To systematically identify and prioritize druggable gene targets for migraine by integrating genetic, transcriptomic, and phenomic data.

- Background: Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) identify loci associated with migraine, but linking these to causal genes and druggable targets requires integration with functional genomic data. This protocol uses Summary-data-based Mendelian Randomization (SMR) to test for putative causal genes, followed by rigorous validation [20].

- Methodology:

- Data Integration: Obtain migraine GWAS summary statistics and expression Quantitative Trait Loci (eQTL) data from relevant tissues (e.g., whole blood and multiple brain regions from GTEx, eQTLGen, PsychENCODE) [20].

- Causal Gene Identification: Perform SMR analysis to test for association between the genetic component of gene expression and migraine risk. Follow with HEIDI test to exclude pleiotropy. Genes passing a False Discovery Rate (FDR) < 0.05 and HEIDI p-value > 0.05 are considered putative causal [20].

- Druggability Assessment: Cross-reference the list of putative causal genes with druggable genome databases (e.g., DGIdb). Annotate genes with known drug targets or those belonging to druggable protein families.

- Validation and Prioritization:

- Colocalization Analysis: Assess if the GWAS and eQTL signals share a single causal variant (posterior probability > 0.8).

- Phenome-Wide Association Study (PheWAS): Screen prioritized genes against a wide range of phenotypes to assess potential on-target side effects.

- Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Network: Map prioritized genes onto PPI networks to identify hub proteins and explore connections to known migraine pathways.

- Expected Outcome: A shortlist of high-confidence, druggable target genes for migraine (e.g., NR1D1, THRA), along with an assessment of their potential safety profile, ready for experimental validation in cellular or animal models.

Diagram 3: Multi-omics pipeline for migraine target discovery and prioritization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools and Resources for Neurological Target Identification

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEURON [16] | Simulation Environment | Biophysically detailed simulations of neurons and networks | Modeling microcircuit changes in epileptic dentate gyrus [16] |

| ModelDB [16] [13] | Online Database | Repository of published, peer-reviewed computational models | Accessing and sharing models of Parkinsonian beta oscillations [13] |

| CELLEX [19] | Algorithm | Calculates cell-type-specific expression profiles from snRNA-seq data | Identifying region-specific gene expression in migraine [19] |

| SMR/HEIDI [20] | Statistical Tool | Performs Mendelian Randomization to find putative causal genes | Integrating GWAS and eQTL data for migraine target discovery [20] |

| DGIdb [20] | Database | Information on druggable genes and drug-gene interactions | Filtering candidate genes for druggability potential [20] |

| MetaCGRP [21] | Machine Learning Model | Predicts CGRP-inhibiting compounds from SMILES notation | Virtual screening of natural products for anti-migraine activity [21] |

| GLP-1 receptor agonist 13 | GLP-1 receptor agonist 13, MF:C25H23ClF2N6O, MW:496.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| TCO-GK-PEG4-NHS ester | TCO-GK-PEG4-NHS ester, MF:C33H52N4O14, MW:728.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Leveraging Neuroimaging and Connectomics to Inform Anatomically Accurate Models

Computational models are revolutionizing our approach to understanding brain function and developing neuromodulation therapies. However, the predictive power and clinical translatability of these models are fundamentally constrained by their biological accuracy. This protocol details the methodology for leveraging non-invasive neuroimaging and connectomics data to build and constrain anatomically precise computational models of brain dynamics. The framework is designed to integrate individual brain architecture, thereby enabling the in-silico optimization of neurostimulation parameters for personalized therapeutic interventions. This process directly addresses the critical translational gap in neuromodulation by providing a mechanistic bridge between brain structure, function, and stimulation outcome [22] [23].

Application Notes: Core Principles and Rationale

The Role of Computational Modeling in Neurostimulation

Incorporating computational models into neuroimaging analytics provides a mechanistic link between empirically observed neural phenomena and abstract mathematical concepts such as attractor dynamics, multistability, and bifurcations [22]. This is particularly vital for neurostimulation, where understanding the transition between brain states is key. Models allow for a thorough exploration of the parameter space—including stimulation intensity, location, and frequency—that is logistically and ethically intractable to probe comprehensively through experimentation alone [22]. For instance, optimization frameworks have been developed for Spinal Cord Stimulation (SCS) that use computational models to rapidly calculate optimal current amplitudes across electrode contacts, a process that would be prohibitively slow and inefficient in a clinical setting [24].

The Necessity of Anatomical Constraint

A "one-size-fits-all" approach to neurostimulation often leads to inconsistent outcomes because it fails to account for inter-individual variability in brain anatomy and network organization [11]. Individual differences in head size and anatomy significantly influence the amount of current that reaches neural tissue [11]. Computational models that are informed by individual structural data can account for this variability. The integration of structural connectomes, derived from dMRI, ensures that the model's wiring diagram reflects the actual physical architecture of an individual's brain, leading to more accurate predictions of stimulation effects [22].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Acquiring the Structural and Functional Connectome

Objective: To reconstruct the individual's structural brain network and map intrinsic functional networks to serve as a scaffold for computational modeling.

Materials and Reagents:

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scanner (3T minimum, 7T preferred for higher resolution).

- T1-weighted MPRAGE sequence protocol.

- Diffusion-weighted MRI (dMRI) sequence protocol (multi-shell, high angular resolution preferred).

- Resting-state functional MRI (fMRI) sequence protocol (EPI BOLD).

- MRI-compatible headphones and padding to minimize head motion.

- Electroencephalography (EEG) system (optional, for complementary temporal data).

Procedure:

- Structural Scan: Acquire a high-resolution T1-weighted anatomical scan (e.g., MPRAGE, voxel size ~1mm³). This image will be used for tissue segmentation and as a reference for aligning other scans.

- Diffusion MRI: Acquire dMRI data using a multi-shell diffusion-encoded sequence. A high number of diffusion directions (e.g., 64+ per shell) is recommended for robust fiber orientation modeling.

- Resting-State fMRI: Acquire a 10-15 minute BOLD fMRI scan while the participant is at rest with eyes open, fixating on a crosshair. Instruct the participant to remain awake and still.

- Preprocessing:

- T1 Processing: Perform brain extraction, tissue segmentation (gray matter, white matter, cerebrospinal fluid), and cortical surface reconstruction using tools like FreeSurfer or FSL.

- dMRI Processing: Correct dMRI data for eddy currents, head motion, and susceptibility-induced distortions using tools like FSL's

eddyandtopup. - fMRI Processing: Discard initial volumes for signal equilibrium, apply slice-timing correction, realign volumes for motion correction, and co-register to the T1 image. Perform additional nuisance regression (white matter, CSF signals, motion parameters) and band-pass filtering (typically 0.01-0.1 Hz).

- Tractography and Structural Connectivity (SC):

- Reconstruct the white matter fibers using a tractography algorithm (e.g., probabilistic tractography in FSL's ProbtrackX or deterministic in MRtrix3).

- Parcellate the brain into distinct regions of interest (ROIs) using a standard atlas (e.g., Desikan-Killiany, AAL) warped to the individual's T1 space.

- Generate an SC matrix where each element (i,j) represents the density of reconstructed streamlines between regions i and j.

- Functional Connectivity (FC):

- Extract the mean BOLD time series from each ROI defined in the parcellation.

- Compute the pairwise Pearson correlation coefficients between all regional time series to create a symmetric FC matrix.

Protocol 2: Building and Personalizing the Whole-Brain Model

Objective: To create a biologically realistic, large-scale computational model where the simulated neural dynamics are constrained by the individual's SC and FC.

Materials and Software:

- High-performance computing (HPC) cluster or workstation.

- Computational modeling software (The Virtual Brain, NEST, or custom code in Python/MATLAB).

- Processed SC and FC matrices from Protocol 1.

Procedure:

- Model Selection: Choose a neural mass model (NMM) to represent the dynamics of each brain region. Common choices include the Wilson-Cowan model, the Jansen-Rit model for EEG rhythms, or the reduced Wong-Wang model for fMRI.

- Model Parameterization:

- Set the structural connectivity matrix from dMRI tractography as the coupling weights between network nodes.

- Incorporate a global coupling parameter (G) that scales the entire SC matrix.

- Include other key parameters such as the synaptic excitation-inhibition balance and conduction delays (estimated from inter-regional fiber lengths).

- Model Personalization and Fitting:

- Simulate the model's BOLD signal using a hemodynamic forward model (e.g., Balloon-Windkessel).

- Compare the simulated FC (the matrix of correlations between simulated BOLD signals of all regions) with the empirical FC from resting-state fMRI.

- Use a global optimization algorithm (e.g., Bayesian optimization, genetic algorithm) to fit the model parameters (like G) by maximizing the similarity between the simulated and empirical FC. The Pearson correlation between the upper triangles of the two FC matrices is a common cost function.

Table 1: Key Parameters for Whole-Brain Model Fitting

| Parameter | Description | Fitting Method |

|---|---|---|

| Global Coupling (G) | Scales the overall strength of input from other nodes. | Optimized to match empirical FC. |

| Signal Transmission Speed | Determines inter-regional conduction delays. | Typically derived from fiber length and a fixed velocity. |

| Local Excitatory-Inhibitory Balance | Governs local node dynamics and oscillatory properties. | Can be optimized or set from literature values. |

| Node Noise | Represents unresolved inputs and background activity. | Fixed to a low level or optimized. |

Protocol 3: In-Silico Optimization of Neurostimulation

Objective: To use the personalized model to predict the optimal stimulation parameters for a given individual and cognitive/clinical target.

Materials and Software:

- Personalized whole-brain model from Protocol 2.

- Finite Element Method (FEM) model of the head and brain.

- Optimization toolbox (e.g., SciPy in Python).

Procedure:

- Electric Field Modeling:

- Create an individual-specific head model (including skin, skull, CSF, gray matter, white matter) from the T1 image.

- Position the simulated neurostimulation electrodes (e.g., for tES or TMS) on the scalp according to the desired montage.

- Use FEM software (e.g, SimNIBS, ROAST) to calculate the electric field (E-field) distribution in the brain for a given stimulation intensity.

- Stimulation Input:

- Map the computed E-field onto the brain parcellation to define the region-specific stimulation input. The input to each node in the model is proportional to the average E-field magnitude in that region.

- Define Optimization Goal:

- Formulate a clear objective. For example: "Maximize the functional connectivity between the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) and the parietal cortex," or "Shift the whole-brain FC pattern towards a healthy template."

- Run In-Silico Trials:

- Simulate the personalized model under a wide range of stimulation parameters (e.g., intensity from 0.5 mA to 2.0 mA, multiple electrode montages).

- For each parameter set, compute the objective function (e.g., change in target FC strength).

- Parameter Optimization:

- Employ an optimization algorithm, such as Bayesian Optimization (BO), to efficiently navigate the high-dimensional parameter space. BO is ideal for this purpose as it builds a probabilistic model of the objective function and aims to find the global optimum with relatively few simulations [11].

- The output is a set of personalized stimulation parameters predicted to maximize the desired neural effect.

Table 2: In-Silico Optimization Parameters for Transcranial Electrical Stimulation

| Parameter | Role in Optimization | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Stimulation Intensity | Primary driver of electric field magnitude. | Follows an inverted U-shape effect; personalized BO can identify the individual "sweet spot" [11]. |

| Electrode Montage | Determines the spatial pattern of the E-field. | Multi-electrode montages create a vast search space, necessitating efficient optimizers [24]. |

| Stimulation Frequency | Targets specific neurophysiological rhythms. | tRNS may benefit lower performers via stochastic resonance [11]. |

| Stimulation Target | The brain region or network to be modulated. | Defined a priori based on the cognitive or clinical target (e.g., dlPFC for attention). |

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow from data acquisition to optimized stimulation parameters.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Resources for Connectome-Informed Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| FreeSurfer | Software Suite | Automated cortical surface reconstruction and brain parcellation from T1-weighted MRI. |

| FSL | Software Suite | A comprehensive library for dMRI and fMRI data analysis, including tractography and connectivity mapping. |

| The Virtual Brain (TVB) | Simulation Platform | A open-source platform for constructing and simulating personalized whole-brain network models. |

| SimNIBS | Software Tool | Calculates the electric field distribution in the brain generated by TMS or tES using individual head models. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Hardware | Provides the computational power required for running thousands of simulations for model fitting and parameter optimization. |

| Bayesian Optimization Library (e.g., Scikit-Optimize) | Software Library | Implements efficient optimization algorithms for navigating high-dimensional parameter spaces with limited samples. |

| 2'-Deoxycytidine-13C9 | 2'-Deoxycytidine-13C9, MF:C9H13N3O4, MW:236.15 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Taltobulin intermediate-11 | Taltobulin intermediate-11, MF:C17H25NO4, MW:307.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The following diagram maps the logical relationships and data flow between the key tools in the research pipeline.

Methodologies in Practice: Building and Applying Computational Frameworks

Multi-scale computational modeling has emerged as a transformative approach in neuroscience, bridging microscopic neuronal processes with macroscopic brain network dynamics to advance neurostimulation optimization. This framework integrates diverse computational techniques—from biophysically detailed single-neuron models to population-level approaches—enabling researchers to uncover mechanisms underlying brain function and pathology while accelerating therapeutic development. This application note provides a comprehensive technical resource detailing methodologies, protocols, and tools for implementing multi-scale modeling approaches, with particular emphasis on their application in neurostimulation research. We present structured quantitative comparisons, experimental workflows, and standardized protocols to support researchers in developing clinically relevant computational models for optimizing neuromodulation therapies.

The brain's complex organization spans multiple spatial and temporal scales, from molecular processes within individual neurons to large-scale networks governing cognitive functions and behavior [25]. Multi-scale computational modeling systematically addresses this complexity by integrating representations across hierarchical levels of neural organization, creating bridges between disparate experimental datasets and facilitating mechanistic insights that cannot be derived from any single scale alone [25] [26]. These approaches have become indispensable for understanding how microscopic phenomena (e.g., ion channel dynamics, synaptic transmission) influence macroscopic brain activity and, ultimately, behavior in both health and disease [25].

In neurostimulation research, multi-scale modeling provides a powerful platform for rational therapy design, addressing the critical challenge of how electrical stimulation parameters interact with neural tissue across spatial scales [27] [28]. By incorporating subject-specific anatomical and physiological data, these models enable researchers to predict neural responses to stimulation, optimize targeting strategies, and elucidate mechanisms of action—all in silico before costly clinical trials [29] [28]. The integration of population-level modeling approaches further enhances these capabilities by accounting for biological variability and enabling robust predictions across diverse individuals [29] [30].

Population Models: Capturing Biological Variability

Conceptual Framework and Applications

Population modeling embraces the inherent biological variability in neuronal systems through approaches that systematically explore parameter spaces rather than focusing on single "canonical" models [30]. Traditional single-model approaches often fail to capture the diversity of neural responses observed experimentally, as they typically incorporate average parameter values that may not produce biologically realistic activity [30]. Ensemble modeling, by contrast, identifies multiple parameter combinations (constituting a "solution space") that generate activity within experimentally observed ranges [30]. This approach has revealed that similar network outputs can emerge from substantially different underlying parameter sets, providing crucial insights into the degeneracy and robustness of neural circuits [30].

Population models are particularly valuable in neurostimulation research for predicting inter-subject variability in response to therapy [29]. For example, realistic head models incorporating anatomical differences demonstrate how individual variations in features such as head size, tissue thickness, and gyrification patterns significantly shape electric fields generated by non-invasive brain stimulation techniques [29]. These differences can result in unintended stimulation outcomes that reduce therapeutic efficacy if not properly accounted for in treatment planning.

Table 1: Population Modeling Approaches and Applications

| Approach | Key Features | Primary Applications | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ensemble Modeling | Identifies multiple parameter sets producing acceptable output; maps "solution spaces" [30] | Understanding degeneracy in neural circuits; predicting variable treatment responses | Stomatogastric ganglion models; cortical network models [30] |

| Virtual Population Cohorts | Multiple realistic head models with anatomical and conductivity variability [29] | Estimating population variability in electric field distributions; stimulation optimization | 100-head model dataset from Human Connectome Project [29] |

| Solution Space Mapping | Systematic exploration of parameter combinations producing target activity [30] | Identifying robust stimulation parameters; understanding parameter interactions | Half-center oscillator parameter analysis [30] |

Technical Implementation and Protocols

Protocol 2.2.1: Developing Virtual Population Head Models for Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation

Purpose: To create a population of realistic head models for estimating inter-subject variability in electric field distributions during non-invasive brain stimulation.

Materials and Software:

- Structural MRI data (T1-weighted and T2-weighted)

- Automated segmentation tools (SimNIBS, FreeSurfer, CAT12)

- Meshing software (GMSH)

- Finite element method solvers

- Programming environment (Python, MATLAB)

Procedure:

- Subject Selection: Select a representative cohort of imaging datasets. For example, the 100-model dataset derived from the Human Connectome Project s1200 release includes 50 males and 50 females (ages 22-35) [29].

- Tissue Segmentation: Process structural MRI scans through automated segmentation pipelines to identify different tissue types (skin, skull, cerebrospinal fluid, gray matter, white matter, eyes) [29].

- Mesh Generation: Convert segmentations into finite-element meshes suitable for electromagnetic simulations. Typical models contain 5-6 million tetrahedral elements [29].

- Quality Assurance: Manually inspect segmentations and meshes for anatomical accuracy and mesh degeneracy. Perform corrections as needed and apply quality metrics to ensure simulation stability [29].

- Conductivity Assignment: Assign tissue-specific conductivity values, incorporating biological variability by sampling from plausible distributions (e.g., Beta(3,3) distribution for scalp, skull, and gray matter conductivities) [29].

- Lead-Field Computation: Generate lead-field matrices for efficient electric field calculations across multiple stimulation configurations [29].

Applications:

- Estimation of population variability in electric field distributions for given stimulation parameters

- Optimization of stimulation protocols for robust targeting across diverse individuals

- Meta-analysis of brain stimulation studies through standardized simulation environments [29]

Protocol 2.2.2: Ensemble Modeling for Neural Circuit Analysis

Purpose: To identify multiple parameter combinations that produce biologically plausible network activity, capturing the degeneracy and variability inherent in neural systems.

Materials and Software:

- Computational models of neurons and networks (e.g., Hodgkin-Huxley type models)

- Parameter sampling algorithms (random sampling, evolutionary algorithms)

- High-performance computing resources

- Activity analysis tools for quantifying output features

Procedure:

- Define Target Ranges: Establish acceptable ranges for network output measures (e.g., burst period, spike frequencies, phase relationships) based on experimental observations [30].

- Select Parameter Space: Identify key parameters to vary (e.g., maximal conductance densities, synaptic strengths) and their plausible ranges [30].

- Sample Parameter Combinations: Systematically explore the parameter space using appropriate sampling strategies (random sampling, Latin hypercube sampling, or more efficient directed searches) [30].

- Simulate and Evaluate: For each parameter combination, run simulations and evaluate whether the resulting activity falls within target ranges [30].

- Analyze Solution Space: Characterize the distribution of acceptable parameter sets and identify correlations between parameters that maintain functional output [30].

Applications:

- Understanding how variable underlying parameters can produce similar functional outputs

- Identifying robust therapeutic targets that remain effective across biological variability

- Predicting which parameter changes might destabilize network function in disease states [30]

Detailed Neuronal Networks: From Single Cells to Microcircuits

Biophysical Detail in Neuronal Modeling

Biophysically detailed neuronal models simulate the morphological and electrophysiological properties of individual neurons and their synaptic connections, providing mechanistic insights into how molecular and cellular processes shape network dynamics [25] [31]. At the microscopic scale, models incorporate the biophysical properties of neurons and synapses, including neurotransmitter dynamics, receptor interactions, and synaptic vesicle release mechanisms [25]. These models often use established frameworks like the Hodgkin-Huxley formalism to simulate ion channel gating kinetics, providing a foundation for understanding action potential propagation and neuronal excitability [25].

The mesoscale level focuses on microcircuits—localized networks of interconnected neurons that perform specialized computational functions [25]. Advances in connectomics and optogenetics have enabled detailed mapping of these circuits, which underlie core cognitive processes such as memory encoding and sensory processing [25]. Network models at this scale often employ graph theory to capture information flow through neural circuits and incorporate additional complexities such as synaptic plasticity and feedback loops [25].

Table 2: Scales of Detail in Neuronal Network Modeling

| Scale | Key Elements | Modeling Approaches | Simulation Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopic | Ion channels, synapses, single-neuron morphologies [25] | Hodgkin-Huxley formalism, multi-compartment models [25] | NEURON, NeuroML, Arbor [25] [31] |

| Mesoscopic | Local microcircuits, neuronal ensembles [25] | Network models with detailed connectivity, graph theory [25] | NetPyNE, Brian, EDEN [31] |

| Macroscopic | Large-scale brain networks, systems-level dynamics [25] | Neural mass models, dynamic mean field models [25] | The Virtual Brain, TVB) |

Technical Implementation and Protocols

Protocol 3.2.1: Standardized Model Development Using NeuroML

Purpose: To create standardized, shareable, and reproducible models of neurons and networks using the NeuroML ecosystem.

Materials and Software:

- NeuroML Python libraries

- Supported simulators (NEURON, NetPyNE, Brian, Arbor, EDEN)

- Validation and visualization tools

Procedure:

- Model Component Definition: Define model elements (ion channels, cell morphologies, synapse types) using NeuroML's modular structure [31].

- Dynamics Specification: Formalize mathematical descriptions of component dynamics using LEMS (Low Entropy Modeling Specification) to ensure machine-readable definitions [31].

- Network Construction: Assemble cells into networks by specifying connectivity patterns and synaptic properties [31].

- Simulation Configuration: Define simulation parameters, including duration, time step, and output variables [31].

- Model Validation: Use NeuroML's validation tools to verify model structure and dynamics against experimental data [31].

- Simulation Execution: Run simulations across multiple supported platforms to verify reproducibility [31].

- Model Sharing: Archive and share models in standardized NeuroML format through platforms like Open Source Brain (OSB) and NeuroML Database (NeuroML-DB) [31].

Applications:

- Development of FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) models

- Collaborative model building across research groups

- Reproducible simulation of neural dynamics across multiple platforms [31]

Protocol 3.2.2: High-Efficiency Surrogate Modeling for Peripheral Nerve Stimulation

Purpose: To develop highly efficient surrogate models of neural fibers that accurately predict responses to electrical stimulation while dramatically reducing computational costs.

Materials and Software:

- GPU computing resources

- AxonML framework

- Training data from biophysically detailed models (e.g., MRG model in NEURON)

- Optimization algorithms

Procedure:

- Training Data Generation: Use established biophysical models (e.g., MRG model in NEURON) to generate comprehensive datasets of neural responses to varied stimulation protocols [4].

- Surrogate Model Architecture: Implement simplified cable models with trainable parameters that capture essential nonlinear dynamics while reducing computational complexity [4].

- Model Training: Train surrogate models using backpropagation and gradient descent to minimize differences between surrogate predictions and detailed model outputs [4].

- Model Validation: Thoroughly validate surrogate model performance across diverse stimulation parameters, fiber diameters, and nerve morphologies [4].

- Optimization Applications: Employ trained surrogate models for rapid parameter optimization in neurostimulation protocols [4].

Performance Metrics: The S-MF (surrogate myelinated fiber) model demonstrates 2,000 to 130,000× speedup over single-core NEURON simulations while maintaining high accuracy (R² = 0.999 for activation thresholds) [4].

Applications:

- Rapid exploration of large parameter spaces for stimulation optimization

- Real-time parameter adjustment in closed-loop stimulation systems

- Patient-specific treatment planning without prohibitive computational costs [4]

Integrated Multi-Scale Approaches

Bridging Scales in Neurostimulation Research

Integrating models across spatial and temporal scales presents significant challenges but offers powerful insights into neurostimulation mechanisms and optimization [25]. Multi-scale approaches enable researchers to trace how molecular-level disruptions (e.g., ion channel mutations) manifest as circuit-wide abnormalities and ultimately affect whole-brain dynamics and behavior [25]. Emerging technologies are helping to bridge these scales by integrating high-resolution molecular data with large-scale neuroimaging, such as mapping transcriptomic profiles from resources like the Allen Brain Atlas onto large-scale connectomic data [25].

Table 3: Multi-Scale Integration Techniques

| Integration Challenge | Approaches | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Linking Molecular to Cellular Scales | Differentiable neural simulators; integration of transcriptomics and proteomics data [25] | Mapping ion channel mutations to neuronal excitability changes [25] |

| Linking Cellular to Network Scales | Mean-field approximations; simplified neuronal representations; surrogate modeling [4] | S-MF surrogate models for network-level stimulation predictions [4] |

| Linking Network to Systems Scales | Dynamic mean field models; neural mass models; The Virtual Brain platform [26] | Personalizing whole-brain models with individual connectivity data [26] |

| Cross-Species Integration | Comparative anatomy; standardized ontologies; data harmonization [25] | Translation of stimulation parameters from animal models to human applications [25] |

Visualization of Multi-Scale Integration

Multi-Scale Modeling Hierarchy: This diagram illustrates the integration of computational approaches across spatial scales in neuroscience, from molecular to systems levels.

Workflow for Multi-Scale Neurostimulation Optimization

Multi-Scale Neurostimulation Workflow: This diagram outlines an iterative framework for optimizing neurostimulation protocols using multi-scale modeling approaches, incorporating subject-specific data and clinical validation.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Scale Modeling

| Resource | Type | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| NeuroML Ecosystem [31] | Model description standard | Standardized, shareable model development; interoperability across simulators | Creating FAIR models; collaborative modeling; reproducible research [31] |

| SimNIBS [29] | Automated head modeling pipeline | Realistic head model generation from MRI; electric field simulations | Non-invasive brain stimulation optimization; population modeling [29] |

| AxonML/S-MF [4] | Surrogate modeling framework | High-efficiency prediction of neural responses to stimulation | Peripheral nerve stimulation optimization; large parameter sweeps [4] |

| Open Source Brain [31] | Model sharing platform | Collaborative development; model validation; community standards | Sharing and validating models across research groups [31] |

| Virtual Population Datasets [29] | Curated model collections | Population-level analysis; variability assessment; stimulation optimization | Estimating inter-subject variability in electric field distributions [29] |

| Ensemble Modeling Tools [30] | Parameter exploration frameworks | Solution space mapping; robustness analysis; degenerate solutions identification | Understanding parameter interactions in neural circuits [30] |

Multi-scale modeling approaches represent a paradigm shift in computational neuroscience, providing powerful frameworks for understanding complex brain dynamics and optimizing neurostimulation therapies. By integrating across spatial and temporal scales—from ion channels to whole-brain networks—these approaches enable researchers to address fundamental questions about how neural activity emerges from biological components and how it becomes disrupted in disease states. The protocols, tools, and methodologies outlined in this application note provide practical guidance for implementing these approaches in neurostimulation research, with particular emphasis on addressing biological variability through population modeling and capturing mechanistic details through detailed neuronal networks. As these methods continue to evolve and incorporate increasingly sophisticated machine learning techniques and high-performance computing capabilities, they promise to accelerate the development of personalized, effective neuromodulation therapies for a wide range of neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Patient-specific modeling represents a paradigm shift in computational neuroscience and neurostimulation, moving away from standardized approaches to methodologies that incorporate individual anatomical and connectivity profiles. This approach is grounded in the understanding that each human brain possesses a unique neuroanatomical architecture [32] and a distinctive fine-scale connectome structure that is not captured by coarse-scale models [33]. The integration of these individual features enables researchers and clinicians to develop more precise neurostimulation interventions with improved target engagement and reduced variability in outcomes.

The clinical imperative for personalization is particularly evident in neurological disorders such as stroke, where lesions disrupt network dynamics in ways that vary substantially between individuals [34]. Similarly, in neuromodulation therapies, the interaction between stimulation parameters and individual brain anatomy significantly influences the distribution of induced electric fields [35]. This protocol details methodologies for creating and utilizing patient-specific models that integrate individual anatomy and connectivity profiles to optimize neurostimulation parameters, with applications spanning research and clinical domains.

Theoretical Foundation

Individuality of Brain Anatomy and Connectivity

The scientific rationale for patient-specific modeling rests on substantial evidence of inter-individual variation in neuroanatomy and connectivity. Research demonstrates that individual subjects can be accurately identified based solely on their brain anatomical features using standard classification techniques [32]. This individuality emerges from a complex interaction of genetic, non-genetic biological, and environmental influences that shape the brain's morphological characteristics.

At the connectome level, fine-scale structural features exhibit remarkable individuality that is shared across brains but inaccessible to coarse-scale models [33]. These shared fine-scale elements represent a major component of the human connectome that coexists with traditional areal structure. The ability to project individual connectivity data into a common high-dimensional model enables researchers to account for significantly more variance in human connectome organization than previously possible, revealing structure closely related to fine-scale distinctions in information representation.

Impact on Neurostimulation Outcomes

The clinical significance of this inter-individual variation becomes apparent in neurostimulation applications, where anatomical differences substantially influence stimulation dosage and localization. Table 1 summarizes key quantitative evidence supporting the need for patient-specific approaches in neurostimulation.

Table 1: Quantitative Evidence Supporting Patient-Specific Neurostimulation Approaches

| Evidence Type | Standardized Approach Performance | Personalized Approach Performance | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electric Field Intensity [35] | 0.113 ± 0.028 V/m (mean ± SD) | 0.290 ± 0.005 V/m (mean ± SD) | Personalization reduces variability and improves target engagement |

| Inter-Subject Variability [35] | Levene's test F(1,18)=12.02, p=0.00275 | Significantly reduced variance | Personalized montages produce more consistent outcomes across subjects |

| Surgical Efficiency [36] | Multiple needle insertions (conventional) | Mean 1.2 insertions (personalized) | 3D modeling reduces operative time and improves accuracy |

| Foramen Localization [36] | Extended localization time (conventional) | Mean 0.8 minutes (personalized) | Patient-specific planning streamlines surgical workflow |

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Implementing patient-specific modeling requires specialized computational tools and resources. Table 2 catalogs essential research reagents and computational solutions referenced in the literature.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Patient-Specific Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| BrainX3 [34] | Neuroinformatics Platform | Visualization, analysis, and simulation of neuroimaging data and brain models | Stroke rehabilitation, lesion identification, whole-brain modeling |

| U-Net Architecture [34] | Convolutional Neural Network | Automated lesion segmentation from multi-modal MRI data | Stroke lesion identification and classification |

| FreeSurfer [32] | Software Suite | Extraction of cortical and subcortical anatomical measures from MRI | Brain feature quantification, cortical thickness, surface area, volume |

| 3D Printed Neurostimulator [35] | Hardware Device | Patient-specific electrode placement for transcranial electrical stimulation | Home-based tES therapy with precise electrode positioning |

| Linear Discriminant Analysis [32] | Statistical Classification | Subject identification based on neuroanatomical features | Quantification of individual neuroanatomical variation |

| Weighted K-Nearest Neighbor [32] | Statistical Classification | Alternative method for subject identification | Comparison with LDA for neuroanatomical individuality assessment |

| MindStim Clinical Trial Platform [35] | Research Infrastructure | Validation of personalized montages through in-silico modeling | Electric field optimization and target engagement assessment |

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Patient-Specific Head Model Creation for Transcranial Electrical Stimulation

Objective: To create individualized head models from structural MRI data for optimizing tES electrode montages and predicting electric field distributions.

Materials and Equipment:

- Structural MRI scans (T1-weighted, minimum 1mm³ resolution)

- Computational resources for finite element method (FEM) modeling

- Software for multi-layer tissue segmentation (e.g., SimNIBS, ROAST)

- 3D printer for creating patient-specific electrode caps (optional)

Methodology:

Image Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Acquire high-resolution T1-weighted MRI scans with whole-head coverage