Chronic Stability Assessment of Implantable Electrodes: Strategies for Long-Term Reliability in Neural Interfaces

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical factors influencing the long-term stability and performance of implantable electrodes for neural interfaces.

Chronic Stability Assessment of Implantable Electrodes: Strategies for Long-Term Reliability in Neural Interfaces

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical factors influencing the long-term stability and performance of implantable electrodes for neural interfaces. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the biological, material, and mechanical challenges that compromise chronic electrode functionality. The scope spans from foundational mechanisms of foreign body response and glial scarring to advanced methodological approaches for stability assessment, troubleshooting strategies for performance optimization, and comparative validation of emerging technologies. By synthesizing current research and clinical evidence, this review offers a structured framework for developing next-generation bioelectronic implants with enhanced chronic stability for therapeutic and diagnostic applications.

The Biological Battlefield: Understanding Fundamental Stability Challenges in Neural Electrodes

The development of advanced implantable medical devices, particularly neural electrodes, represents a frontier in treating neurological diseases and restoring lost functions. However, a significant biological barrier limits their widespread clinical adoption: the foreign body response (FBR). This inevitable host reaction to implanted materials initiates a cascade of inflammatory and fibrotic processes that severely impair device functionality over time [1] [2]. For implantable electrodes, which require stable, intimate contact with target tissues, the FBR presents a critical challenge to long-term performance [2] [3].

The FBR begins with tissue injury during implantation, triggering acute inflammation characterized by immune cell recruitment [1]. Without successful degradation of the implant, this response transitions to a chronic fibrotic phase marked by dense extracellular matrix deposition and fibrous capsule formation [1] [2]. This capsule functionally isolates the implant from surrounding tissue, disrupting the precise interface necessary for effective signal recording or stimulation [2]. Understanding these mechanisms is paramount for developing next-generation bioelectronic medicines with improved chronic stability.

Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of FBR

The Cellular Cascade of Foreign Body Reaction

The FBR follows a well-defined temporal sequence of cellular events that begins immediately upon implantation:

Protein Adsorption: Within seconds of implantation, blood-derived proteins (albumin, fibrinogen) non-specifically adsorb to the implant surface, creating a provisional matrix through which cells interact with the foreign material [2] [4]. This protein layer undergoes dynamic changes through the Vroman effect, where smaller proteins are progressively replaced by larger ones [2].

Neutrophil Infiltration: Within minutes, neutrophils migrate to the implantation site as first responders [2]. They adhere to the protein layer and release factors including reactive oxygen species (ROS) and proteolytic enzymes that promote inflammatory progression [2] [5]. This initial wave of neutrophils typically disappears within two days [2].

Monocyte Recruitment and Macrophage Differentiation: Chemical signals from neutrophils, blood clotting, and mast cells attract monocytes to the site [2]. Upon arrival, monocytes differentiate into macrophages that proliferate and populate the lesion [2]. These macrophages mediate the core inflammatory response by releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNFα, IL-1b, IL-6, and IL-8 [2].

Frustrated Phagocytosis: Macrophages adhere to the implant surface through integrins (particularly αMβ2) and attempt to engulf the device [2]. When unable to phagocytose large implants, they enter a state of "frustrated phagocytosis," secreting degrading enzymes and ROS that can damage otherwise stable biomaterials [2] [5].

Fibrotic Encapsulation: If the implant persists, the response transitions to a chronic fibrotic stage characterized by a shift from pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages to anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages [2]. Fibroblasts activate and differentiate into myofibroblasts, secreting collagen that forms a dense, avascular fibrous capsule around the implant [4].

Key Signaling Pathways in Pathological FBR

Recent research has identified RAC2 signaling as a central mediator of pathological FBR. Analysis of human fibrotic capsules from various implant types revealed that severe FBR is characterized by upregulation of this hematopoietic-specific Rho-GTPase, which functions as a mechanical signal transducer [6]. RAC2 guides the expression of genes involved in both cell-activating and inflammatory pathways, driving the pathological FBR independently of implant material properties [6].

The diagram below illustrates the key cellular and molecular events in the foreign body response:

Figure 1: Cellular and Molecular Cascade in Foreign Body Response. The FBR progresses through acute and chronic phases, with RAC2 mechanotransduction signaling identified as a key driver of pathological outcomes.

Impact of FBR on Neural Electrode Performance

Functional Consequences of FBR on Recording Stability

The foreign body response directly impairs neural electrode function through multiple mechanisms that degrade recording quality over time:

Increased Electrode-Tissue Distance: Glial scar formation creates a physical barrier between recording electrodes and target neurons, increasing the effective distance for signal transmission [3]. Since electrodes typically record from neurons within 100 μm, even minimal encapsulation can significantly attenuate signals [3].

Elevated Interface Impedance: The fibrous capsule, composed largely of insulating proteins and cells, increases interfacial impedance at the electrode-tissue boundary [7] [3]. This impedance rise directly reduces the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of recorded neuronal activities [3].

Neuronal Loss: Chronic inflammation surrounding implants creates a neurotoxic environment through pro-inflammatory cytokines and free radicals, leading to neuronal death in the immediate vicinity of the probe [3]. This depletes the very signal sources the electrodes are designed to detect.

Microglial Adhesion: Emerging evidence suggests that microglia adhering directly to electrode surfaces, rather than the multicellular scar itself, may be the primary cause of performance deterioration [8]. These surface-adherent microglia can degrade recording quality without full scar formation.

Quantitative Assessment of FBR Impact on Electrode Performance

Table 1: Comparative Performance Metrics of Neural Electrodes Affected by Foreign Body Response

| Electrode Type | Recording Duration | Signal Attenuation | Impedance Change | Key FBR Manifestations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon-based Michigan Probes [3] | Months | Progressive decline in single-unit yield | Significant increase over time (~30-50%) | Gliosis, neuronal death, chronic BBB disruption |

| Flexible Polyimide Electrodes [7] | Up to 8 months | More stable than rigid probes | Lower initial rise but still significant | Reduced glial scarring compared to rigid probes |

| NeuroRoots Filament Electrodes [7] | 7 weeks | Maintained signal quality | Minimal change when functional | Distributed design minimizes FBR |

| Utah Arrays [3] | Years in humans | Gradual decline in channel functionality | Progressive increase | Dense fibrous encapsulation, vascular disruption |

| Carbon Fiber Microelectrodes [7] | Several months | Improved chronic stability | Stable low impedance | Reduced mechanical mismatch |

Comparative Analysis of Electrode Design Strategies

Material and Geometrical Optimization for FBR Mitigation

Innovative electrode designs employ various strategies to minimize the foreign body response through material selection and geometrical optimization:

Flexible Materials: Flexible electrodes with low Young's modulus (typically <1 MPa) better match brain tissue mechanics (1-10 kPa), reducing chronic inflammation and mechanical mismatch [7] [9] [3]. The bending stiffness of these devices is typically below 10â»â¹ Nm, compared to >10â»â¶ Nm for rigid devices [9].

Miniaturization: Reducing electrode cross-sectional area to subcellular dimensions minimizes acute injury during implantation and promotes better integration [7]. Nanowire electrodes with cross-sectional areas as small as 10 μm² have demonstrated reduced FBR [7].

Surface Topography: Engineering surface features at micro/nano scales can modulate protein adsorption and immune cell responses [4]. Specific topographies reduce macrophage attachment and foreign body giant cell formation compared to smooth surfaces [4].

Implantation Techniques: The coordination of electrode shape with implantation method significantly affects initial tissue damage [7]. Unified implantation uses a single guidance system for multiple electrodes, while distributed implantation deploys electrodes individually to minimize cross-sectional area [7].

Comparative Performance of Different Electrode Designs

Table 2: Foreign Body Response to Different Neural Electrode Designs and Materials

| Design Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Effect on FBR | Limitations | Recording Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flexible Polymer Electrodes (Polyimide, SU-8) [7] [3] | Reduced mechanical mismatch with neural tissue | Significantly reduced glial scarring compared to rigid probes | Require temporary stiffeners for implantation | Months to >1 year with moderate signal decay |

| Ultra-Small Footprint Electrodes (NeuroRoots, nanowires) [7] | Minimal tissue displacement and damage during implantation | Greatly reduced acute and chronic inflammation | Manufacturing complexity, handling challenges | Several weeks to months with stable signals |

| Surface-Modified Electrodes (Biomimetic coatings) [7] [4] | Modulates protein adsorption and immune cell response | Reduced macrophage activation and fibrosis | Long-term coating stability concerns | Improved short-term performance, variable long-term |

| Drug-Eluting Electrodes (Anti-inflammatory releases) [7] | Localized immunosuppression around implant site | Attenuated inflammatory response and glial scar | Finite drug reservoir, potential tissue toxicity | Initial stability may decline after drug depletion |

Experimental Approaches for FBR Investigation

Standardized Methodologies for FBR Assessment

Rigorous assessment of FBR and its impact on electrode performance requires standardized experimental approaches:

Histological Analysis: Post-explantation evaluation of tissue samples using specific markers for glial cells (GFAP for astrocytes, Iba1 for microglia), neurons (NeuN), and inflammatory cells (CD68 for macrophages) [3]. Fibrosis is quantified through collagen staining (Masson's Trichrome, Picrosirius Red) [5] [6].

Electrophysiological Recording: Chronic tracking of signal quality metrics including signal-to-noise ratio, single-unit yield, local field potential power, and electrode impedance [8] [3]. Correlation of these parameters with histological findings establishes structure-function relationships.

Immunohistochemical Workflow:

- Perfusion fixation and brain extraction

- Sectioning and antibody labeling for target proteins

- Confocal microscopy and image analysis

- Quantification of cell densities and distances from implant track

- Statistical correlation with recording performance [3]

In Vivo Functional Testing: For neural interfaces, assessment of decoding performance in brain-machine interface applications provides functional readouts of FBR impact [7]. Deterioration in control accuracy correlates with the extent of FBR.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Foreign Body Response

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Function in FBR Investigation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immune Cell Markers | Iba1 (microglia), CD68 (macrophages), GFAP (astrocytes) | Immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry | Identification and quantification of specific immune cell populations |

| Cytokine Inhibitors | CSF1R inhibitors, RAC2 inhibitors [8] [6] | Pharmacological modulation of FBR | Testing causal relationships between specific pathways and FBR severity |

| Extracellular Matrix Stains | Picrosirius Red, Masson's Trichrome | Histological assessment | Collagen visualization and fibrotic capsule quantification |

| Mechanical Testing Systems | Custom vibrating implants [6] | Application of controlled mechanical forces | Investigation of mechanotransduction in FBR pathogenesis |

| Transgenic Animal Models | RAC2 knockout mice [6] | Genetic manipulation of FBR pathways | Establishing molecular mechanisms of FBR in controlled systems |

| Dehydroeffusol | Effusol | High-Purity Research Compound | Effusol for research applications. This compound is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Spirostan-3-ol | Spirostan-3-ol | High-Purity Steroid Reference Standard | High-purity Spirostan-3-ol for steroid biosynthesis & pharmacology research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

Emerging Strategies and Future Directions

Advanced Approaches for FBR Mitigation

Several innovative strategies show promise for overcoming FBR challenges in next-generation neural interfaces:

Active Anti-inflammatory Approaches: Controlled release systems delivering anti-inflammatory agents (e.g., dexamethasone) directly from the electrode surface [7]. These systems can be engineered for temporal profiles matching the FBR progression.

Biomimetic Surface Modifications: Coating electrodes with bioactive peptides or extracellular matrix components that mimic natural tissue environments [5] [4]. These coatings reduce protein fouling and discourage immune recognition.

Mechanotransduction Modulation: Targeting specific mechanosensitive pathways, particularly RAC2 signaling in myeloid cells, which has been identified as a key mediator of pathological FBR [6]. Pharmacological inhibition of RAC2 shows promise in reducing FBR severity.

Adaptive Electrode Systems: Self-adjusting electrodes that can modify their position or properties in response to tissue changes, maintaining optimal interface despite encapsulation [3].

The relationship between implant properties and FBR severity, along with corresponding mitigation strategies, can be visualized as follows:

Figure 2: Relationship Between Implant Properties and FBR Severity with Corresponding Mitigation Strategies. Key design parameters influence FBR severity, while emerging strategies target these parameters to improve biocompatibility.

The foreign body response remains the fundamental challenge to achieving stable long-term performance in implantable neural electrodes. While traditional approaches focused primarily on material biocompatibility, contemporary research reveals the critical importance of mechanical matching, geometrical optimization, and active immunomodulation. The recognition that RAC2-mediated mechanotransduction drives pathological FBR independently of material chemistry represents a paradigm shift in the field [6].

Future progress will likely involve combinatorial approaches that integrate flexible material platforms with surface modifications, controlled drug delivery, and sophisticated implantation techniques. The ultimate goal is developing truly "bio-integrative" electrodes that become functionally incorporated into neural tissue without provoking destructive immune responses. Achieving this milestone will require continued multidisciplinary collaboration between materials science, immunology, and clinical neurology to translate laboratory innovations into reliable clinical solutions for patients with neurological disorders.

The development of implantable neural electrodes represents a frontier in treating neurological disorders and advancing brain-computer interfaces (BCIs). A central challenge undermining their long-term effectiveness is the profound mechanical mismatch between conventional electrode materials and the neural tissues they interface with. Brain tissue is exceptionally soft, fragile, and dynamic, with a Young's modulus typically ranging from 1 to 10 kPa [10] [11]. In contrast, traditional electrode materials, such as silicon (≈102 GPa) and platinum (≈102 MPa), are several orders of magnitude stiffer [11]. This mechanical disparity creates a significant foreign body reaction, leading to inflammation, scar tissue formation, and eventual electrode failure [7] [12].

This review objectively compares the performance of different neural electrode technologies, focusing on how their mechanical properties influence chronic stability. We summarize experimental data quantifying this mismatch, detail methodologies for assessing interface stability, and provide a toolkit of key reagents and materials. Framed within the broader thesis of chronic stability assessment, this guide serves researchers and scientists in selecting and developing neural interfaces that bridge the stiffness gap for long-term functional integration.

Comparative Analysis of Electrode Properties and Performance

The shift from rigid to soft and flexible bioelectronics is a defining trend in the field, aimed at mitigating mechanical mismatch [9]. The table below provides a quantitative comparison of the core properties of these two electrode classes.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Rigid vs. Soft/Flexible Neural Electrodes

| Property | Rigid Bioelectronics | Soft and Flexible Bioelectronics |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Material Types | Silicon, metals, ceramics [9] | Polymers, elastomers, hydrogels, thin-film materials, meshes [9] |

| Young’s Modulus | > 1 GPa [9] | 1 kPa – 1 MPa (typically) [9] |

| Bending Stiffness | > 10–6 Nm [9] | < 10–9 Nm [9] |

| Tissue Integration | Stiffness mismatch causes inflammation and fibrotic encapsulation [9] | Soft, conformal materials match tissue mechanics and reduce immune response [9] |

| Chronic Signal Fidelity | Long-term degradation due to micromotion and scar tissue [9] | Better chronic signal due to more stable tissue contact [9] |

| Implantation Challenge | Mechanically stable but causes significant acute tissue damage [7] | Requires rigid shuttles or stiffness enhancement for implantation [7] |

The performance consequences of these material choices are clear. Flexible electrodes, with their lower bending stiffness, are designed to mimic the softness of brain tissue, which reduces the risk of chronic inflammation and mechanical mismatch [7]. However, their inherent flexibility complicates implantation, often necessitating rigid shuttles or temporary stiffeners [7]. In vivo, the foreign body response to stiff implants involves activated microglia and proliferating astrocytes, which secrete cytokines and extracellular matrix components that ultimately form a compact, insulating glial scar around the electrode [7]. This scar tissue increases the distance between neurons and electrode sites, causing rapid signal attenuation and a sharp rise in impedance, ultimately degrading the electrode's function [7] [12].

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing the Interface

A critical aspect of chronic stability research involves rigorous experimental characterization of the mechanical properties of both the neural tissue and the electrode, as well as the biological response post-implantation.

Characterizing Brain Tissue Mechanics

Accurately measuring the mechanical properties of brain tissue is challenging due to its ultrasoft, fragile, and heterogeneous nature [10]. Both invasive and non-invasive techniques are employed:

- Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM): This technique operates by detecting the contact interaction between an indenter tip and the tissue surface, providing force-displacement curves with piconewton-scale sensitivity. It is ideal for measuring mechanical properties at the micro- and nanoscale, revealing heterogeneity across different brain regions [10].

- Indentation (IND): A versatile platform for probing spatially resolved modulus and time-dependent viscoelastic behaviors of brain tissue [10].

- Magnetic Resonance Elastography (MRE): A non-invasive technique that measures brain tissue mechanical properties in vivo by analyzing the propagation of shear waves through the brain using MRI. It supports population-level studies and longitudinal monitoring within a single individual [10].

Table 2: Techniques for Characterizing Brain Tissue Mechanical Properties

| Technique | Spatial Scale | Measurable Parameters | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Cellular / Subcellular | Young's Modulus at micro-scale | High resolution for assessing tissue heterogeneity |

| Indentation (IND) | Mesoscale | Spatially resolved modulus, viscoelastic properties | Versatile; allows testing of time-dependent behavior |

| Magnetic Resonance Elastography (MRE) | Organ (in vivo) | Shear stiffness, storage, and loss moduli | Non-invasive, suitable for longitudinal human studies |

Quantifying Electrode Degradation and Biocompatibility

To assess the long-term stability of electrodes, explant analysis and biological response characterization are essential.

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) for Explanted Electrodes: A seminal study analyzed 980 explanted microelectrodes from three human participants after 956–2130 days of implantation. Using SEM, researchers quantified physical degradation types (e.g., "cracked" or "pockmarked" surfaces) and correlated these findings with in vivo functional metrics like signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), impedance, and stimulation performance. This method provides a direct link between material integrity and clinical functionality [13].

- Drug-Release Coatings for Biocompatibility: A novel method to improve biocompatibility involves covalent binding of the anti-inflammatory drug dexamethasone onto a polyimide electrode surface. The experimental protocol involves:

- Chemically activating and modifying the polyimide surface.

- Covalently binding dexamethasone to the activated surface.

- Implanting the modified device in vivo.

- Assessing the slow release of the drug over at least two months and quantifying the reduction in immune cell signals and scar tissue formation compared to control implants [14].

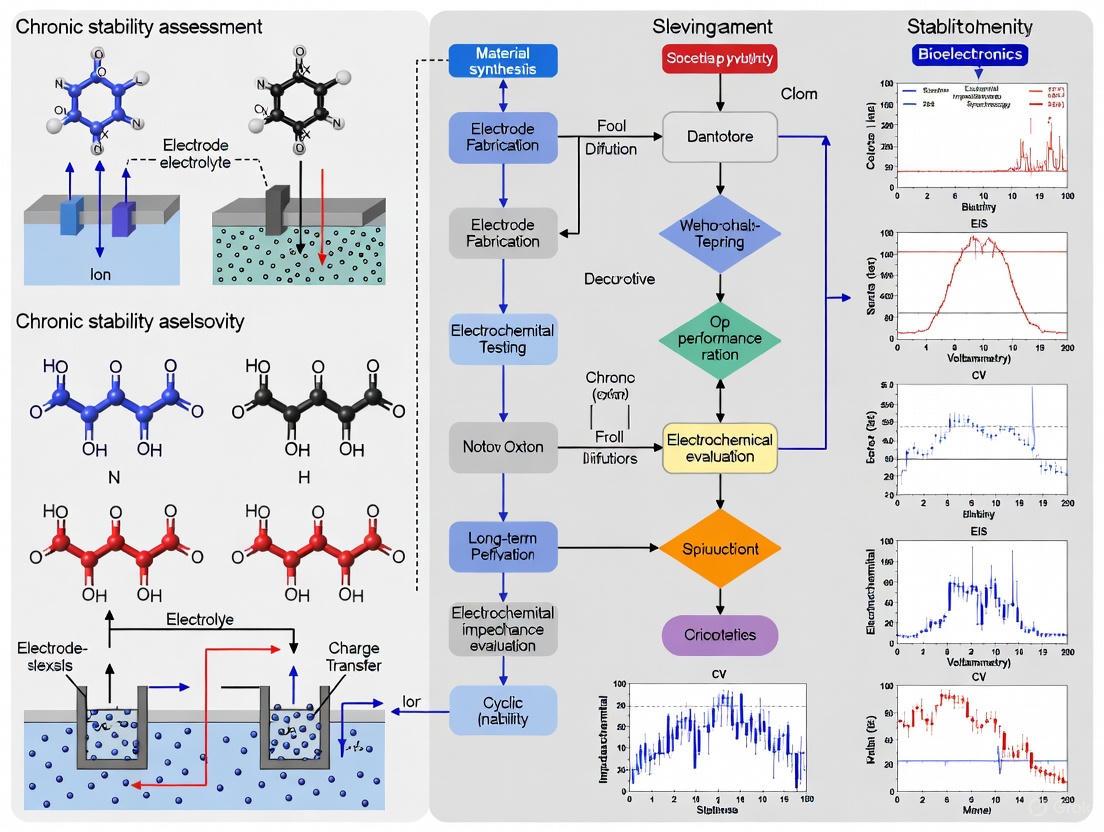

The workflow for a comprehensive chronic stability study, from material characterization to functional validation, can be visualized as follows:

Diagram 1: Chronic Stability Assessment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

To conduct the experiments described above, researchers rely on a suite of specialized materials and reagents. The following table details key items essential for working in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Neural Interface Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Polyimide | A flexible polymer commonly used as a substrate or insulation for implantable electrodes [7] [14]. | Serves as the base material for flexible neural interfaces; can be surface-modified for drug delivery [14]. |

| Dexamethasone | A potent anti-inflammatory drug used to modulate the immune response at the implant-tissue interface [14]. | Covalently bound to electrode surfaces (e.g., polyimide) to create a localized, slow-release coating that reduces scar formation [14]. |

| Iridium Oxide | A conductive coating applied to electrodes to improve their electrical properties and charge injection capacity [12] [13]. | Used as a coating on electrode sites (e.g., Sputtered Iridium Oxide Film - SIROF) to enhance recording and stimulation performance [13]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | A biocompatible polymer used as a temporary coating or adhesive. | Used as a temporary coating to fix a flexible electrode to a rigid tungsten wire shuttle during implantation; melts upon insertion to release the shuttle [7]. |

| Sputtered Iridium Oxide Film (SIROF) | An advanced electrode coating material with excellent charge transfer capabilities. | Used on electrode tips; studies show SIROF electrodes are twice as likely to record neural activity than platinum despite showing different degradation patterns [13]. |

| 6-Amino-1-hexanol | 6-Amino-1-hexanol | High-Purity Reagent Supplier | 6-Amino-1-hexanol is a bifunctional reagent for organic synthesis & bioconjugation. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Batoprazine | Batoprazine HCl | SERT/NET Inhibitor | For Research | Batoprazine is a potent SERT/NET inhibitor for depression & anxiety research. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

Overcoming the mechanical mismatch at the neural interface requires a multi-faceted approach. No single strategy is sufficient; instead, integration is key. The path forward involves the synergistic combination of passive and active strategies [7]. Passively, electrodes must be designed with geometries and mechanical properties that minimize initial damage and chronic micromotion, effectively making the device "invisible" to the immune system [7]. Actively, surfaces can be functionalized to biochemically modulate the local environment, such as through the controlled release of anti-inflammatory drugs like dexamethasone to promote tissue repair and integration [14] [7].

The relationship between these integrated strategies and their collective impact on long-term stability is summarized below:

Diagram 2: Integrated Stability Strategies

As quantitative degradation studies in humans demonstrate [13], the clinical success of BCIs depends on overcoming these persistent material challenges. The future of stable implantable electrodes lies in the continued development and intelligent integration of advanced material science, sophisticated engineering, and biological modulation to finally bridge the stiffness gap for the lifetime of the patient.

The successful long-term operation of implantable neural electrodes is a cornerstone of modern neuroscience research and the development of advanced brain-computer interfaces (BCIs). These technologies enable unprecedented access to neural circuits, providing insights into brain function and offering therapeutic pathways for neurological disorders [11]. However, their chronic stability is severely compromised by the brain's inherent biological response to implanted devices, primarily gliosis and glial scar formation [15] [16]. This tissue reaction creates a physical and biological barrier that insulates the electrode from its target neurons, leading to a progressive decline in the quality of recorded neural signals and the efficacy of electrical stimulation over time [3] [11].

The core of the problem lies at the biotic-abiotic interface. Despite the shift from rigid to more flexible electrode materials to improve mechanical compatibility, the implantation of any device inevitably triggers a cascade of immune responses [7]. This begins with an acute inflammatory reaction due to mechanical mismatch and vascular damage during insertion, and evolves into a chronic foreign body reaction (FBR) characterized by the activation of microglia and astrocytes [7] [15]. These reactive glial cells proliferate, migrate toward the injury site, and ultimately form a dense, encapsulating sheath around the implant—the glial scar [7] [3]. This scar tissue, rich in glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and inhibitory extracellular matrix (ECM) components like chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs), acts as an insulating layer [17] [18]. It increases the distance between neurons and recording sites, causes a sharp rise in electrode impedance, and attenuates signal amplitude, culminating in the functional failure of the neural interface [7] [16]. Understanding and mitigating this gliotic barrier is therefore critical for advancing chronic stability assessment of implantable electrodes.

The Biological Cascade: From Implantation to Insulating Scar

The formation of the gliotic barrier is a dynamic, multi-stage process initiated at the moment of electrode insertion. The following diagram illustrates the key stages and primary cell types involved in this response.

The biological response begins with acute injury during device insertion. The mechanical trauma ruptures blood vessels, disrupting the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and allowing serum proteins like albumin and fibronectin to infiltrate the brain tissue [15]. This breach is a primary trigger for the activation of the brain's resident immune cells, microglia, within hours [7] [17]. Activated microglia adopt an amoeboid morphology, proliferate, and migrate to the implant surface, releasing a storm of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [3] [19]. These cytokines contribute to a toxic environment for neurons and initiate the activation of astrocytes [15].

Over the following days and weeks, the response transitions to a chronic phase dominated by reactive astrocytes [17]. Driven by signaling from activated microglia and other damage-associated cues, astrocytes undergo reactive astrogliosis—a process characterized by cellular hypertrophy, proliferation, and a marked upregulation of intermediate filaments like GFAP [3] [15]. These reactive astrocytes densely populate the area around the implant, extending elongated processes that progressively form a tight, encapsulating border. As this border matures over weeks, it evolves into a dense glial scar [7] [17]. The scar tissue is not purely cellular; reactive astrocytes and infiltrating fibroblasts deposit inhibitory ECM molecules, most notably CSPGs, which further contribute to the scar's inhibitory properties by physically and chemically blocking axon regeneration [20] [18]. The final result is a compact, insulating sheath that surrounds the chronic implant.

Quantitative Impact: Comparing the Gliotic Barrier's Effect on Electrode Performance

The functional consequences of gliosis and scar formation are quantifiable and critically impact key electrode performance metrics. The following table summarizes the primary effects and their direct impact on signal recording and stimulation.

Table 1: Quantitative Impacts of Gliosis on Neural Electrode Performance Parameters

| Performance Parameter | Impact of Gliosis/Scar Formation | Consequence for Neural Interface |

|---|---|---|

| Electrode Impedance | Sharp increase due to insulating cellular/ECM barrier [16] | Reduced signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and increased power requirements for stimulation [11] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Progressive decline as scar tissue increases distance to neurons [3] | Loss of single-neuron resolution; inability to isolate action potentials [16] |

| Single-Unit Yield | Gradual decrease over weeks/months post-implantation [3] [16] | Reduced number of detectable and trackable neurons, limiting experimental and BCI throughput [3] |

| Neuronal Density | Significant loss of neurons within 100–150 μm of the electrode interface [3] | Fewer signal sources available for recording, contributing to signal decay [3] |

The most direct electrical impact is a significant rise in electrode impedance at the electrode-tissue interface. The glial scar, comprising cells and ECM proteins, acts as an electrical insulator, impeding the flow of current between the electrode and the brain tissue [16]. This increased impedance detrimentally affects both recording and stimulation. For recording, it leads to a lower SNR, as the tiny electrical signals from neurons are more easily lost in background noise [11]. For stimulation, more power is required to deliver the same amount of current to the neural tissue.

Furthermore, the physical separation caused by the encapsulating scar layer directly translates to signal attenuation. The amplitude of detectable neural signals, particularly action potentials from individual neurons, decays exponentially with distance. Even a scar thickness of tens of micrometers can significantly reduce spike amplitudes, making them undetectable above the noise floor [3]. This effect, combined with the actual death of neurons in the immediate vicinity of the implant due to neuroinflammatory processes and excitotoxicity, leads to a progressive drop in the number of recordable single units (single-unit yield) over time [3] [16]. This loss of stable single-unit recordings is a primary failure mode for chronic neuroscience experiments and clinical BCIs that rely on decoding precise neural spiking activity.

Methodologies for Assessing Gliosis and Scar Formation in Preclinical Models

Rigorous and standardized experimental protocols are essential for quantifying the foreign body response and evaluating new electrode technologies or anti-fibrosis strategies. The following workflow outlines a standard methodology for a correlated, multi-modal assessment.

The standard approach involves a correlative methodology that combines chronic electrical monitoring with post-mortem histological analysis. First, the electrode of interest is implanted into the target brain region (e.g., motor cortex, hippocampus) of an animal model, typically rodents or non-human primates [7]. For chronic electrical assessment, impedance spectroscopy and SNR tracking are performed regularly over the implantation period (e.g., weeks to months). These functional measurements provide a direct, time-lapsed view of device performance degradation [16].

Upon completion of the in vivo study, animals are perfused transcardially with a fixative like 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) to preserve the tissue architecture. The brain is extracted, and the tissue block containing the implant track is cryo-sectioned or paraffin-embedded and sliced into thin sections (e.g., 10-40 μm thick) for histological analysis [15]. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is the primary tool for visualizing the cellular components of the FBR. Standard protocols involve blocking with serum, followed by incubation with primary antibodies against key biomarkers:

- Anti-GFAP: To label reactive astrocytes and quantify glial scar thickness and density [3] [15].

- Anti-Iba1: To identify activated microglia and macrophages, assessing their morphology and distribution around the implant [15].

- Anti-NeuN: To label neuronal nuclei and quantify neuronal density and loss in the peri-implant region [3].

Fluorescent or chromogenic detection is used, often with counterstains like DAPI for nuclei. Additional stains, such as antibodies against CSPGs (e.g., CS-56), are used to label the inhibitory ECM of the scar [20] [18]. Finally, high-resolution confocal or fluorescence microscopy is employed to image the tissue sections. Quantitative image analysis software is then used to measure key metrics, including the thickness of the GFAP+ scar capsule, the density of Iba1+ cells, and the number of NeuN+ neurons at various distances from the electrode track [15] [16]. The final, critical step is to correlate these histological endpoints with the chronic electrical recording data to establish a direct link between the degree of gliosis and the decline in electrophysiological performance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Gliosis Assessment

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Analyzing the Foreign Body Response

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Anti-GFAP Antibody | Primary antibody for immunohistochemical labeling of reactive astrocytes; essential for quantifying glial scar formation [3] [15]. |

| Anti-Iba1 Antibody | Primary antibody for identifying activated and resting microglia/macrophages in the tissue surrounding the implant [15]. |

| Anti-NeuN Antibody | Primary antibody for staining neuronal nuclei, enabling quantification of neuronal survival and density near the electrode interface [3]. |

| Chondroitin Sulfate Proteoglycan (CSPG) Antibody (e.g., CS-56) | Labels the inhibitory extracellular matrix deposited within the glial scar, a key contributor to its barrier properties [20] [18]. |

| 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Standard fixative solution for perfusing animals and post-fixing brain tissue to preserve cellular morphology and antigenicity for histology [15]. |

| DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) | Fluorescent nuclear counterstain that allows for visualization of all cell nuclei in a tissue section, used for cell counting and orientation. |

| Ethyl chrysanthemate | Ethyl Chrysanthemate | High-Purity | For Research |

| epi-Eudesmol | 10-epi-gamma-Eudesmol CAS 15051-81-7 |

Engineering Strategies to Mitigate the Gliotic Barrier

The pursuit of chronic stability has driven innovation in neural interface design, focusing on material properties, device geometry, and active biological modulation to minimize the FBR. A primary strategy involves reducing the mechanical mismatch between the rigid implant and the soft brain tissue (Young's modulus ~1-10 kPa) [11]. This has led to the development of flexible electrodes using polymers like polyimide or Parylene C, and ultrasmall, filamentary designs such as nanoelectronic threads (NETs) [7] [21]. These devices have a lower bending stiffness, which mitigates chronic micromotion-induced inflammation and reduces the strain on surrounding tissue [7] [16].

Complementing this passive approach are active bio-integration strategies. These include surface functionalization of electrodes with bioactive molecules like laminin or polyethylene glycol (PEG) to improve biocompatibility and reduce protein adsorption [7]. A more advanced tactic is the incorporation of controlled-release systems from the electrode itself, designed to locally deliver anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., dexamethasone) or molecules that inhibit specific signaling pathways involved in astrocyte activation and scar formation [7]. For instance, targeting the IL-20 cytokine pathway with a neutralizing antibody (7E) has been shown in a spinal cord injury model to reduce glial scar formation and improve functional recovery, presenting a potential target for future neural interfaces [19].

Table 3: Comparison of Neural Probe Designs and Their Chronic Performance

| Probe Design/Strategy | Key Characteristics | Reported Impact on Chronic Gliosis & Recording Stability |

|---|---|---|

| Silicon Probes (Michigan, Neuropixels) | Rigid substrate (Silicon), high electrode count, precise geometry [3] [16] | Significant glial scarring and neuronal loss; recording instability over weeks; often requires microdrives for repositioning [3] [16]. |

| Flexible Polymer Probes | Low Young's modulus (e.g., Polyimide, SU-8), better mechanical match to tissue [7] [21] | Reduced chronic inflammation and glial scarring compared to rigid probes; improved long-term signal stability but require stiff temporary shuttles for implantation [7]. |

| Ultrasmall/Filamentary Probes (e.g., NeuroRoots, Carbon Fibers) | Minute cross-sectional area (< 10 μm width/diameter), "invisible" to immune system [7] | Minimal acute damage and chronic FBR; stable recordings reported for months; limited channel count per shank and handling challenges [7]. |

| Drug-Eluting Coatings | Local release of anti-inflammatory agents (e.g., Dexamethasone) from electrode surface [7] | Demonstrated suppression of reactive astrocytes and microglia in vicinity of implant; maintains lower impedance and higher SNR in chronic phase [7]. |

The formation of a gliotic scar represents the most significant biological barrier to the long-term stability and high-fidelity performance of implantable neural electrodes. While the field has made substantial progress in understanding this complex immune response and in developing engineering solutions to mitigate it—such as flexible materials, miniaturized geometries, and bioactive coatings—the challenge is not yet fully solved. The future of chronically stable neural interfaces lies in the continued blurring of the line between living tissue and man-made device [3]. This will likely be achieved through multi-faceted approaches that combine the mechanical stealth of next-generation flexible and injectable electronics [21] with the biological intelligence of immuno-modulatory surface treatments and closed-loop drug delivery systems that actively intervene to prevent scar formation only when necessary. Furthermore, the adoption of advanced assessment techniques, including transcriptomics to map the full molecular landscape of the FBR, will provide deeper insights and new targets for intervention [16]. By systematically addressing the insulating barrier of gliosis, researchers can pave the way for neural interfaces that remain stable and functional for a lifetime, unlocking their full potential for neuroscience and transformative clinical therapies.

Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption and Its Role in Sustaining Neuroinflammation

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is a highly specialized, semi-permeable interface between the central nervous system (CNS) and the systemic circulation that dynamically regulates the bidirectional exchange of fluids, molecules, and cells [22]. This sophisticated biological barrier protects the brain from harmful substances while maintaining the precise chemical environment necessary for optimal neural function. Histologically, the BBB comprises non-fenestrated endothelial cells that form the capillary walls, supported by pericytes embedded in the basement membrane, and enveloped by astrocyte endfeet that create an intimate interaction with the vascular system [22]. These cellular components collectively form the neurovascular unit (NVU), which includes additional elements such as perivascular macrophages, microglia, and neurons that contribute to BBB function and regulation [23].

At the molecular level, the exceptional impermeability of the BBB arises from complex protein networks that create tight junctions between endothelial cells. These junctions consist of transmembrane proteins including occludin, claudins (particularly claudin-5), and junctional adhesion molecules, which are linked intracellularly to zonula occludens proteins (ZO-1, ZO-2) that anchor the junctional complexes to the actin cytoskeleton [23]. Adherens junctions composed of vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-cadherin) provide additional intercellular adhesion and stability [22]. The cerebral endothelial glycocalyx, a thick layer of proteoglycans, glycoproteins, and glycolipids on the luminal surface, serves as the first physical barrier of the BBB and plays a crucial role in regulating vascular permeability and immune cell adhesion [22].

When the BBB becomes compromised through various pathological mechanisms, its disruption initiates and sustains neuroinflammation through multiple pathways. The breakdown of this critical barrier allows uncontrolled entry of blood-derived components, immune cells, and inflammatory mediators into the CNS, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of inflammation and neuronal damage [22]. This review examines the mechanisms linking BBB disruption to sustained neuroinflammation, with particular emphasis on implications for chronic stability assessment of implantable neural electrodes, highlighting current research methodologies and experimental approaches for investigating these complex interactions.

Mechanisms of BBB Disruption in Neuroinflammation

Molecular Mechanisms of Barrier Breakdown

BBB disruption in neuroinflammatory conditions occurs through multiple interconnected molecular pathways that compromise endothelial integrity. Inflammatory mediators such as cytokines and chemokines play a pivotal role in initiating these changes. Recent research has identified that NLRP3 activation in neutrophils induces BBB disruption via CXCL1/2 secretion and subsequent activation of the CXCL1/2-CXCR2 signaling axis, which directly reduces Claudin-5 expression in brain endothelial cells, increasing paracellular permeability [24]. This pathway represents a crucial mechanism by which innate immune cells directly modulate BBB integrity during neuroinflammation.

The tight junction proteins between endothelial cells undergo significant alterations under inflammatory conditions. Sleep restriction studies in mouse models have demonstrated progressive BBB permeability increases correlated with decreased expression of tight junction proteins claudin-5, occludin, and zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) [25]. These structural changes are accompanied by pericyte detachment from the capillary wall, further destabilizing the neurovascular unit [25]. Complement system activation, particularly increased levels of the C3 component, contributes to BBB dysfunction by binding to C3aR on endothelial cells and reducing trans-endothelial electric resistance [25].

Recent research has also identified TDP-43 depletion in endothelial cells as a significant mechanism in BBB disruption associated with neurodegenerative diseases. Loss of this RNA-binding protein in endothelial cells leads to reduced nuclear β-catenin and downregulation of β-catenin-dependent genes, coupled with elevated TNF/NF-κB signaling, creating a disease-associated endothelial phenotype that compromises BBB function [26]. This mechanism appears particularly relevant in Alzheimer's disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and frontotemporal degeneration, suggesting a common pathway in proteinopathic neurodegeneration.

Cellular Senescence and BBB Dysfunction

Cellular senescence has emerged as a critical mechanism linking chronic neuroinflammation to persistent BBB disruption. Sleep restriction studies in young mice have demonstrated progressive increases in senescence markers (β-galactosidase and p21) in cerebral cortex and hippocampus, accompanied by astroglial reactivity and complement activation [25]. These senescent cells exhibit a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), characterized by secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1α, IL-8, IL-1β, and IL-6, which further perpetuates neuroinflammation and barrier dysfunction [25].

The relationship between cellular senescence and BBB disruption creates a vicious cycle in which neuroinflammation promotes senescence, and senescent cells release inflammatory mediators that further compromise barrier function. This phenomenon has been observed not only in aging but also in response to various stressors, including sleep deprivation, where senescence markers increase progressively alongside BBB hyperpermeability [25]. This mechanism may explain why BBB disruption often persists even after the initial insult has resolved, particularly in conditions such as long COVID-associated cognitive impairment [27].

Table 1: Key Molecular Mechanisms in BBB Disruption

| Mechanism | Key Components | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Junctional Disassembly | Reduced claudin-5, occludin, ZO-1 | Increased paracellular permeability |

| Cellular Senescence | β-galactosidase, p21, SASP factors | Chronic low-grade neuroinflammation |

| Inflammatory Signaling | CXCL1/2-CXCR2 axis, TNF/NF-κB | Enhanced leukocyte adhesion & migration |

| Complement Activation | C3 component, C3aR binding | Reduced trans-endothelial resistance |

Consequences of BBB Disruption on Neural Tissue

Neuroinflammatory Cascade and Neuronal Damage

Breakdown of the BBB initiates a neuroinflammatory cascade characterized by activation of glial cells and infiltration of peripheral immune cells. When the barrier becomes compromised, serum proteins, inflammatory mediators, and peripheral immune cells gain access to the CNS parenchyma, triggering microglial activation and astrocyte reactivity [3]. Activated microglia release pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1, TNF-α, and IL-6, which further amplify the inflammatory response and contribute to neuronal damage [3]. Reactive astrocytes undergo morphological and functional changes characterized by increased expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and contribute to inflammatory signaling through production of cytokines and complement components [25].

The sustained neuroinflammation resulting from BBB disruption creates an environment that promotes neuronal dysfunction and ultimately cell death. Pro-inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species generated by activated immune cells exhibit direct neurotoxicity and disrupt normal neuronal signaling [3]. This neuroinflammatory environment has been particularly well-documented in long COVID-associated cognitive impairment, where BBB disruption correlates with significant cognitive deficits, commonly referred to as "brain fog" [27]. The observation that BBB disruption precedes classical Alzheimer's disease pathology and brain atrophy suggests it may be an early driver rather than merely a consequence of neurodegenerative processes [26].

Implications for Neural Interface Technology

The chronic foreign body response to implanted neural electrodes shares remarkable similarities with neuroinflammatory responses to BBB disruption. Conventional rigid neural probes trigger persistent inflammation characterized by gliosis (formation of glial scars) and neuronal death in proximity to the implant [3]. The mechanical mismatch between rigid electrodes and surrounding brain tissue creates ongoing micro-movements that sustain chronic inflammation, activate microglia, and perpetuate BBB disruption [3]. This inflammatory microenvironment leads to the formation of a dense glial scar around implanted electrodes, composed primarily of reactive astrocytes and microglia, which increases the distance between recording electrodes and target neurons, elevates interfacial impedance, and causes progressive signal quality degradation over time [3].

Table 2: Consequences of BBB Disruption on Neural Function

| Consequence | Key Features | Impact on Neural Function |

|---|---|---|

| Gliosis | Reactive astrocytes, glial scar formation | Physical barrier between electrodes and neurons |

| Neuronal Death | Loss of neurons near injury/implant | Reduced signal sources for recording |

| Chronic Inflammation | Persistent cytokine release, oxidative stress | Progressive tissue damage & dysfunction |

| Immune Cell Infiltration | Neutrophils, T-cells, monocytes | Amplification of inflammatory response |

The compromised BBB allows serum proteins and other neurotoxic substances to enter the brain parenchyma, where they exacerbate inflammation and contribute to neuronal injury. In the context of neural interfaces, this phenomenon is particularly detrimental as the barrier disruption permits serum components to leak into the tissue surrounding implants, further accelerating the foreign body response and device failure [3]. Understanding these shared mechanisms provides valuable insights for developing strategies to improve the chronic stability of implantable neural interfaces.

Experimental Models and Assessment Methodologies

In Vivo Assessment Techniques

Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI) has emerged as a powerful non-invasive technique for quantifying BBB permeability in living subjects. This methodology has been successfully employed to demonstrate BBB disruption in patients with long COVID-associated cognitive impairment, providing direct clinical evidence of barrier breakdown in humans [27]. The technique involves serial T1-weighted imaging following intravenous administration of gadolinium-based contrast agents, with mathematical modeling of contrast agent kinetics to calculate permeability surface area products and fractional leakage rates.

Evans blue and sodium fluorescein permeability assays represent well-established methodologies for quantifying BBB disruption in animal models. In this protocol, Evans blue (which binds serum albumin) and sodium fluorescein are administered intravenously, followed by a circulation period and subsequent transcardial perfusion to remove intravascular tracer [25]. Brain regions are then dissected, homogenized, and tracer extravasation quantified using fluorescence or spectrophotometric detection. This approach has demonstrated progressive BBB permeability increases following sleep restriction in mice, with significant leakage observed after 3, 5, and 10 days of restriction [25].

Two-photon intravital microscopy (TP-IVM) enables real-time visualization of neurovascular dynamics in living animals. This technique employs fluorescent dextrans of varying molecular weights to assess vascular permeability and immune cell trafficking. In studies of NLRP3 activation, 10-kDa Texas Red-dextran extravasation served as a sensitive indicator of BBB disruption, with intensity outside vessels quantitatively measuring permeability [24]. This methodology allows longitudinal assessment of barrier function and direct observation of neutrophil migration patterns in the cortical vasculature.

Molecular and Cellular Analysis Methods

Western blot analysis of tight junction proteins provides quantitative assessment of molecular correlates of BBB integrity. Standard protocols involve homogenizing brain tissue samples (e.g., cerebral cortex and hippocampus), separating proteins by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis, transferring to PVDF membranes, and probing with antibodies against claudin-5, ZO-1, occludin, and other junctional components [25]. Ponceau red staining typically serves as a loading control for normalization. This technique has confirmed reduced expression of tight junction proteins following sleep restriction in mice [25].

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) enable precise quantification of inflammatory mediators in brain tissue and biological fluids. Multiplex Luminex and ProcartaPlex panels permit simultaneous measurement of numerous cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-4, IL-10), chemokines, growth factors, and markers of endothelial activation in serum, plasma, and brain homogenates [27]. This approach has identified distinct inflammatory profiles in patients with COVID-19-associated neurological symptoms, including elevated S100β, a marker suggestive of BBB dysfunction [27].

Flow cytometry with intravascular staining distinguishes between vascularly confined and parenchymal immune cells in CNS inflammation models. This protocol involves intravenous administration of anti-CD45 antibody several minutes before perfusion, which labels only circulating leukocytes without penetrating the intact BBB [24]. Subsequent flow cytometric analysis of brain homogenates allows precise determination of neutrophil and T-cell infiltration into the CNS parenchyma, providing quantitative data on immune cell trafficking across the disrupted BBB.

Research Reagent Solutions for BBB Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for BBB Investigation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| BBB Permeability Tracers | Evans blue, sodium fluorescein, Texas Red-dextran conjugates | Quantitative assessment of barrier integrity in vivo |

| TJ Protein Antibodies | Anti-claudin-5, anti-ZO-1, anti-occludin | Western blot, immunohistochemistry for junctional integrity |

| Cytokine Detection | Multiplex Luminex panels, ELISA kits for TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 | Quantification of inflammatory mediators |

| Cell Type Markers | Anti-GFAP (astrocytes), Iba1 (microglia), CD146 (pericytes) | Immunohistochemical cell identification and quantification |

| Molecular Biology | Primers for β-catenin targets, NF-κB pathway genes | qPCR analysis of BBB-relevant signaling pathways |

Signaling Pathways in BBB Disruption

The following diagram illustrates key signaling pathways involved in blood-brain barrier disruption during neuroinflammation, integrating multiple mechanisms identified from recent research:

Schematic of Key BBB Disruption Pathways: This diagram integrates multiple mechanisms identified in recent research, including NLRP3-CXCR2 signaling [24], TDP-43 loss with β-catenin/NF-κB dysregulation [26], and tight junction protein alterations [25] [22].

Implications for Neural Interface Development

The relationship between BBB disruption and sustained neuroinflammation presents significant challenges for chronically implanted neural interfaces. The foreign body response to implanted electrodes shares fundamental mechanisms with neuroinflammatory cascades triggered by BBB breakdown, including persistent activation of microglia and astrocytes, release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and recruitment of peripheral immune cells [3]. These processes culminate in the formation of glial scars around implants, which electrically isolate electrodes from their target neurons and degrade recording and stimulation performance over time [3].

Advanced electrode design strategies focused on reducing mechanical mismatch with brain tissue show promise for mitigating these inflammatory responses. Flexible neural interfaces with low bending stiffness and Young's modulus comparable to brain tissue (approximately 1-10 kPa) significantly reduce chronic inflammation and glial scarring compared to conventional rigid electrodes [7]. Innovative approaches include ultra-flexible mesh electrodes, filamentous designs with cross-sectional areas at the subcellular level, and bioresorbable supporting structures that provide temporary rigidity during implantation before dissolving to leave only compliant components [7]. These engineering solutions directly address the mechanical factors that contribute to sustained BBB disruption and neuroinflammation around neural implants.

Surface functionalization strategies offer complementary approaches to improve biocompatibility. Anti-inflammatory coatings with controlled drug release systems can actively suppress local immune responses, while biomimetic surface modifications promote integration with neural tissue [7]. The development of neural interfaces that minimize BBB disruption and subsequent neuroinflammation represents a critical frontier in creating stable, long-term brain-computer interfaces for both basic research and clinical applications.

BBB disruption represents a critical mechanism in initiating and sustaining neuroinflammation across diverse neurological conditions, from neurodegenerative diseases to foreign body responses against implanted neural interfaces. The molecular mechanisms underlying this relationship—including tight junction disassembly, cellular senescence, and inflammatory signaling pathways—create self-perpetuating cycles of barrier dysfunction and CNS inflammation. Advanced assessment methodologies, including DCE-MRI, intravital microscopy, and molecular profiling techniques, provide powerful tools for investigating these complex interactions. For neural interface technology, addressing the shared mechanisms of BBB disruption and neuroinflammation through innovative electrode designs and surface modifications offers the most promising path toward achieving stable long-term performance. Future research integrating BBB protection strategies with neural interface development will be essential for creating next-generation devices that maintain signal fidelity over chronic timescales while minimizing tissue damage.

For researchers and drug development professionals working in neurotechnology, the long-term stability of implantable electrodes is a paramount concern. A critical factor determining the success of chronic neural interfaces is the biological response at the electrode-tissue interface, particularly neuronal death. This review objectively compares the performance of different electrode technologies, focusing on how their design and implantation strategies influence neuronal survival and, consequently, the fidelity and longevity of signal acquisition. The chronic stability of an implantable electrode is not merely a function of its electrical properties but is intrinsically linked to its biocompatibility and ability to minimize trauma during and after implantation [7] [28]. The foreign body response, culminating in glial scar formation around the implant, creates a physical barrier that increases the distance between neurons and recording sites. This leads to signal attenuation and a sharp rise in impedance, ultimately compromising the electrode's function [7]. Therefore, understanding and mitigating the causes of neuronal death in the electrode vicinity is a fundamental prerequisite for developing next-generation, high-performance neural interfaces for chronic applications.

Mechanisms of Neuronal Death and Signal Degradation

The process of neuronal degradation and signal loss around implanted electrodes is a complex cascade initiated by the body's immune response. The initial implantation causes acute injury, damaging blood vessels and neuronal tissue, which triggers a release of inflammatory factors [7]. This mechanical mismatch between the electrode and the soft brain tissue (Young's modulus of approximately 1–10 kPa) is a primary source of this trauma [7]. Over time, this acute response can evolve into a chronic inflammatory state. Microglia are activated and release inflammatory cytokines, while astrocytes proliferate and migrate to the injury site, secreting extracellular matrix components [7].

The culmination of this process is the formation of a dense glial scar, which acts as an insulating layer around the electrode [7]. The scar tissue increases the physical distance between viable neurons and the electrode's recording sites, leading to a marked decline in signal quality. This insulation effect results in signal attenuation and a sharp increase in impedance, degrading the electrode's performance for both recording and stimulation purposes [7]. This mode of failure, driven by changes in the biological environment, often occurs in parallel with intrinsic device failures such as corrosion, delamination, or insulation failure of the electrode itself [28]. The diagram below illustrates this sequential relationship between implantation, the immune response, and the final degradation of signal quality.

Comparative Performance of Electrode Technologies

Different electrode technologies interact with neural tissue in distinct ways, leading to varying levels of neuronal death and signal stability. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from chronic studies of three electrode types: flexible deep brain interfaces, peripheral nerve cuff electrodes, and endovascular stent-electrode arrays.

Table 1: Chronic Performance Comparison of Implantable Electrode Technologies

| Electrode Technology | Typical Host Structure | Key Metrics for Chronic Stability | Reported Longevity & Performance Data | Advantages / Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flexible Deep Brain Electrode [7] [28] | Brain Parenchyma | Glial scar formation, Immuno-response, Intrinsic device failure | Recording stability: up to 8 months in cortex; Stimulation stability: considerably less [7] [28] | + Lower mechanical mismatch [7]– Challenging implantation; requires rigid shuttle [7] |

| Spiral Nerve Cuff Electrode [29] | Peripheral Nerve | Nerve conduction velocity, Stimulation threshold, Muscle selectivity | Stable thresholds after ~20 weeks; Selective activation maintained for 3 years [29] | + Stable long-term recruitment [29]– Requires surgical access to nerve [29] |

| Endovascular Stent-Electrode (Stentrode) [30] [31] | Superior Sagittal Sinus | Motor signal modulation, Electrode impedance, Resting state band power | Stable movement modulation & impedance over 12 months [30] [31] | + Minimally invasive implantation [30]– Signal source is field potentials, not single units [30] |

A critical experimental finding from studies on spiral nerve cuff electrodes is the timeline for stabilization. In human subjects, the stimulation thresholds for these electrodes were found to stabilize after approximately 20 weeks post-implantation, providing a crucial timeframe for assessing the settling of the acute biological response [29]. Furthermore, the variability in activation over time was found to be no different from that of traditional muscle-based electrodes used in functional electrical stimulation systems, indicating that the nerve-electrode interface can achieve a level of stability suitable for clinical applications [29].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Electrode Impact and Neuronal Health

To objectively compare electrode technologies and their impact on neuronal health, standardized experimental protocols are essential. The following methodologies are critical for evaluating the chronic performance and biological integration of neural interfaces.

Chronic In Vivo Implantation and Functional Assessment

This protocol is used for long-term evaluation of electrode stability and its functional impact on the surrounding neural tissue, particularly in motor-related applications [29] [30].

- Electrode Implantation: The electrode (e.g., spiral nerve cuff, stentrode, or flexible array) is surgically implanted in the target structure (peripheral nerve, superior sagittal sinus, or brain parenchyma) [29] [30].

- Post-Surgical Recovery & Stabilization: Following implantation, a period of several weeks is allowed for the initial tissue response and electrode encapsulation to stabilize. Shoulders may be immobilized for 3 weeks in the case of peripheral implants [29].

- Exercise Regime: Subjects perform daily exercise sessions to increase the strength and endurance of the target muscles, which also conditions the electrode-tissue interface [29].

- Data Collection Sessions: Data collection begins after the initial stabilization period. Twitch recruitment curves are generated by sending single stimulation pulses and recording the muscle electromyograms (EMG). The activation level is quantified as the area under the rectified EMG response between 5 and 40 ms post-stimulus to eliminate artifact and reflexive contributions [29].

- Long-Term Monitoring: Functional testing occurs over months to years. Metrics include stimulation thresholds, nerve conduction velocity, and for recording electrodes, motor signal modulation (e.g., in high-frequency bands of 30–200 Hz) and electrode impedance [29] [30].

High-Density Multi-Electrode Array (hd-MEA) Analysis of Network Activity

This in vitro protocol uses high-density arrays to monitor the functional effects of interventions, like radiation or toxicological agents, on neuronal networks, providing insights into how similar processes might affect neurons near an implant [32].

- Tissue Preparation: Prefrontal cortex (PFC) or other brain region slices are prepared and maintained in vitro.

- Experimental Intervention: Slices are subjected to the intervention under study (e.g., escalating doses of radiation) using a robotic platform [32].

- hd-MEA Recording: Neural activity is recorded across thousands of channels (e.g., 4,096) to capture extracellular action potentials with high spatial and temporal resolution [32].

- Signal Processing: Voltage deflections (multi-unit spikes) are detected by applying a threshold below the mean voltage. The rate of neural activity at individual channels is computed as the average number of threshold-crossing events per second [32].

- Network Analysis: Key metrics are extracted:

- Firing Rate: The average number of spike events per second across the network.

- Functional Connectivity: Correlations between all pairs of channels on the hd-MEA, with a cut-off (e.g., r = 0.2) applied to reject weak correlations.

- Graph-Theoretic Metrics: Measures such as modularity and global efficiency are calculated to characterize network topology [32].

- Apoptosis Staining: Propidium iodide or other staining is used to quantify a dose-dependent effect on apoptosis, linking functional changes to cell death [32].

The workflow for the hd-MEA protocol, from tissue preparation to data analysis, is visualized below.

Mitigation Strategies for Enhanced Long-Term Stability

The search for chronically stable neural interfaces has led to several innovative strategies focused on mitigating the foreign body response and preventing neuronal death. These can be broadly categorized into passive and active approaches.

Passive Strategies: Material and Design Optimization: The core of this approach is to make the electrode "invisible" to the immune system by minimizing the mechanical mismatch. This involves using flexible materials with a low Young's modulus that closely match that of brain tissue (~1-10 kPa) [7]. Further, optimizing the electrode's geometric shape and implantation cross-sectional area is crucial to reduce acute injury during insertion. Surface functionalization of electrodes with bioactive coatings is another passive strategy to enhance biocompatibility and integration [7].

Active Strategies: Anti-Inflammatory Drug Release: This approach aims to actively modulate the tissue environment post-implantation. It involves integrating drug-controlled release systems into the electrode design [7]. These systems can release anti-inflammatory substances or neurotrophic factors locally to suppress the immune response, promote tissue repair, and support neuronal survival around the implant site [7].

The most advanced solutions likely involve a synergistic combination of these strategies, where the electrode's physical properties are optimized to minimize initial damage, and its surface is engineered to actively maintain a healthy neuronal environment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and reagents essential for research in neuronal health and electrode performance.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Neural Interface Research

| Item Name | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Spiral Nerve Cuff Electrode [29] | Chronic stimulation and recording from peripheral nerves. | Multi-contact design; spiral shape allows for nerve expansion; used for selective muscle activation. |

| Stentrode (Endovascular Electrode Array) [30] [31] | Minimally invasive recording of motor cortex signals from a blood vessel. | 16-channel stent-electrode array; deployed in superior sagittal sinus. |

| High-Density Multi-Electrode Array (hd-MEA) [32] | High-resolution mapping of network activity in brain slices. | 4,096 recording channels; captures population firing rates and functional connectivity. |

| Activated Caspase-3 (aCasp3) Antibody [33] | Immunohistochemical marker for apoptotic cells. | Early marker of irreversible entry into apoptosis; labels dying neurons. |

| Propidium Iodide [32] | Fluorescent stain for identifying dead cells in a population. | Stains cells with compromised membranes; used to quantify apoptosis. |

| Polyimide-based Flexible Electrode [7] [28] | Substrate for thin-film, flexible neural interfaces. | Biocompatible polymer; provides mechanical flexibility; used as substrate and insulation. |

| Parylene-C [28] | Conformal coating for neural implant insulation. | Biocompatible polymer; provides a moisture barrier and electrical insulation. |

| Ag/AgCl Pseudo Reference Electrode [34] [35] | Provides a stable reference potential in electrochemical setups. | Common in screen-printed and implantable sensors; potential is stable in controlled ionic environments. |

| Cuminaldehyde | Cuminaldehyde, CAS:122-03-2, MF:C10H12O, MW:148.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Diisohexyl phthalate | Diisohexyl Phthalate|Plasticizer for Research | Diisohexyl phthalate is a dialkyl phthalate ester used as a plasticizer in polymer research. This product is for research use only and not for human use. |

Assessment Armamentarium: Methodologies for Evaluating Electrode Performance and Stability

For researchers developing chronic implantable electrodes, ensuring long-term electrochemical stability at the neural interface is paramount. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) serves as a powerful, non-invasive diagnostic tool for tracking interface degradation and assessing the performance of electrode materials under realistic conditions. This technique probes the electrical properties of the electrode-electrolyte interface, revealing critical information about charge transfer efficiency, corrosion processes, and the onset of material failure that directly impacts device functionality and biological safety [36] [37].

This guide compares the chronic performance of leading electrode material technologies—specifically, thin-film metallization and titanium nitride (TiN) nanostructures—by examining experimental EIS data and complementary electrochemical assessments. We provide structured comparisons and detailed methodologies to inform material selection and testing protocols for next-generation neural interfaces.

Experimental Protocols for EIS in Chronic Stability Assessment

EIS Measurement Methodology

A standard EIS experiment involves applying a small-amplitude sinusoidal alternating current (AC) potential to an electrochemical cell (the electrode in contact with electrolyte or biological tissue) and measuring the resulting current response [38] [39]. The core procedural steps are:

- Signal Application: A potentiostat or frequency response analyzer applies a sinusoidal potential signal, ( E(t) = E0 \sin(\omega t) ), where ( E0 ) is the amplitude (typically 1-10 mV to maintain pseudo-linearity) and ( \omega ) is the radial frequency [38] [39].

- Response Measurement: The resulting current signal, ( I(t) = I0 \sin(\omega t + \phi) ), is measured, where ( I0 ) is the current amplitude and ( \phi ) is the phase shift between potential and current [38].

- Frequency Sweep: The experiment is repeated across a wide frequency range, typically from 100 kHz down to 10 mHz or 1 Hz, with measurements often spaced logarithmically [39].

- Impedance Calculation: The complex impedance ( Z(\omega) ) is calculated at each frequency from the potential and current signals: ( Z(\omega) = \frac{E(t)}{I(t)} = Z0 \frac{\cos(\phi) + j \sin(\phi)} = Z{\text{real}} + j Z_{\text{imag}} ) [38] [39].

Data Presentation and Analysis

Impedance data is commonly presented in two primary formats, each offering distinct analytical advantages:

- Nyquist Plot: Plots the negative imaginary impedance (( -Z{\text{imag}} )) against the real impedance (( Z{\text{real}} )) at each frequency. This representation readily reveals the number of time constants in the system (often appearing as semicircles or depressed semicircles) but does not explicitly show frequency information [38] [39].

- Bode Plot: Displays the impedance magnitude (( |Z| )) and phase angle (( \phi )) each against log frequency. This format clearly shows the frequency dependence of the impedance and is useful for identifying the characteristic frequencies of different electrochemical processes [38] [39].

The resulting data is typically analyzed by fitting to an equivalent circuit model, which uses electrical components like resistors, capacitors, and constant phase elements to represent physical processes at the electrode interface (e.g., solution resistance, charge transfer resistance, double-layer capacitance) [38] [40].

Comparative Performance of Electrode Materials

The long-term stability of implantable electrodes is a complex function of material properties, design, and the biological environment. The following table summarizes key performance metrics for different electrode technologies based on chronic in vivo and accelerated in vitro testing.

Table 1: Chronic Performance Comparison of Neural Electrode Materials

| Material & Design | Study Duration | Key EIS Findings (Impedance Magnitude) | Stability & Charge Injection Performance | Noted Failure Modes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thin-Film Metallization (TIME, Pt) | Up to 6 months (Human) | Initial: 21-100 kΩ (varies by patient); Plateau: ~100 kΩ; Some terminals showed decrease to ~73 kΩ [36]. | Stable within safe limits for up to 22 weeks; enabled precise amplitude modulation [36]. | Adhesion loss mitigated by SiC layer; redesign from rectangular to split ground contact reduced mechanical stress [36]. |

| TiN Thin Films | 1000 CV Cycles (In Vitro) | N/A | ~25% capacitance loss under ambient conditions; ~13% capacitance loss under Ar-saturated conditions [37]. | Performance decay linked to surface oxidation and reduced charge storage capacity over time [37]. |

| TiN Nanowires (NWs) | 1000 CV Cycles (In Vitro) | N/A | ~5% capacitance loss under ambient conditions; ~2% capacitance loss under Ar-saturated conditions [37]. | Superior cycling stability with minimal capacitance decay; enhanced charge injection capability [37]. |

Performance Analysis and Material Selection

The data indicates a clear trend: nanostructured materials like TiN nanowires offer superior electrochemical stability compared to their thin-film counterparts. This is attributed to their significantly increased surface area, which provides more active sites for charge transfer and results in higher capacitance and lower impedance [37]. This makes them exceptionally suitable for miniaturized electrodes that require high charge injection capacity within safe voltage limits.

For chronic human implants, mechanical design and material integrity are as critical as electrochemical properties. The success of thin-film electrodes in human trials for up to six months was achieved through iterative design improvements, such as incorporating adhesion layers and optimizing ground contact geometry to mitigate intrinsic stress and prevent delamination [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Materials and Reagents for Electrode EIS Assessment

| Item | Function in EIS Experiment |

|---|---|