Biocompatibility in Organic Bioelectronics: Materials, Mechanisms, and Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive overview of biocompatibility in organic bioelectronics, a field poised to revolutionize medical implants and wearable devices.

Biocompatibility in Organic Bioelectronics: Materials, Mechanisms, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of biocompatibility in organic bioelectronics, a field poised to revolutionize medical implants and wearable devices. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of designing soft, conformable electronic materials that interface seamlessly with biological tissues. The scope spans from core material properties and underlying mechanisms to advanced fabrication techniques for implantable sensors and drug delivery systems. It critically addresses persistent challenges in long-term stability and immune response, while also presenting rigorous in vitro and in vivo validation frameworks. By synthesizing current research and emerging trends, this review serves as a strategic guide for developing the next generation of safe, effective, and clinically viable bioelectronic therapeutics.

The Foundations of Biocompatibility: Why Organic Electronics Uniquely Interface with Biology

The emergence of implantable bioelectronics represents a paradigm shift in therapeutic interventions, offering novel treatments for conditions ranging from neurological disorders to chronic inflammatory diseases. These advanced medical devices interface directly with the body's electrically active tissues to modulate neural activity, monitor physiological signals, and deliver targeted therapies. Unlike traditional pharmaceuticals, bioelectronic medicine operates through precise electrical modulation of specific neural pathways, potentially offering higher specificity and fewer systemic side effects [1]. The fundamental requirement for the successful integration and long-term function of these devices is biocompatibility – the ability of a medical device or material to perform with an appropriate host response in a specific application [2]. For implantable bioelectronics, this extends beyond traditional material safety to encompass seamless integration with biological tissues without provoking adverse immune responses, maintaining stable electrical performance in physiological environments, and ensuring long-term reliability despite continuous mechanical stress from dynamic biological surroundings.

The field of organic bioelectronics has significantly advanced this frontier by developing carbon-based semiconducting materials that uniquely match the mechanical and conduction properties of biological tissues [3]. These materials demonstrate inherent flexibility, biocompatibility, and the capacity to carry both electrical and ionic impulses, making them ideal for interfacing human tissue with electronic technology [4]. This review examines the evolving framework for defining, evaluating, and ensuring biocompatibility for implantable bioelectronics, spanning international standards, material innovation, testing methodologies, and clinical translation challenges.

Regulatory Framework and ISO 10993-1:2025 Updates

The Risk-Based Approach to Biological Evaluation

The International Standard ISO 10993-1 serves as the cornerstone for biological evaluation of medical devices, defining principles and requirements for assessing biological safety within a risk management framework [5]. The 2025 edition represents a significant evolution, creating a tighter integration with the risk management process outlined in ISO 14971. Biological evaluation is now formally positioned as an integral component of the overall risk management process, requiring identification of biological hazards, definition of biologically hazardous situations, and establishment of potential biological harms [6].

This updated framework introduces a structured biological evaluation process that mirrors ISO 14971's lifecycle approach, ensuring biological safety is assessed from initial design through post-market surveillance [6]. The standard now explicitly requires biological risk estimation based on severity and probability of harm, followed by biological risk control measures to mitigate unacceptable risks. This paradigm shift means one cannot effectively implement ISO 10993-1:2025 without simultaneously applying the risk management principles of ISO 14971 [6].

Key Updates in the 2025 Revision

Integration of Foreseeable Misuse: The standard now requires consideration of reasonably foreseeable misuse during biological risk assessment. For example, using a device longer than intended by the manufacturer, resulting in longer exposure duration, must be evaluated. This assessment should leverage post-market surveillance data and clinical literature to identify systematic misuse patterns [6].

Refined Exposure Assessment: The standard provides clearer definitions for determining contact duration, introducing concepts of "total exposure period" (number of contact days between first and last use), "contact day" (any contact within a 24-hour period), and distinctions between "daily contact" and "intermittent contact" [6]. The term "transitory" has been removed while "very brief contact" (less than one minute) remains with the understanding that such exposure typically presents negligible risk of biological harm [6].

Bioaccumulation Considerations: Manufacturers must now assess whether chemicals present in devices are known to bioaccumulate. When bioaccumulation is expected, the contact duration must be classified as long-term (>30 days) unless otherwise justified, requiring deeper material characterization and risk assessment [6].

FDA Guidance and Regulatory Alignment

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration recognizes the ISO 10993 series as Consensus Standards and has published detailed guidance documents specifically addressing the use of ISO 10993-1 for premarket applications [7]. The FDA's guidance incorporates several additional considerations, including risk-based approaches to determine if biocompatibility testing is needed, chemical assessment recommendations, and special considerations for devices with submicron or nanotechnology components or in situ polymerizing materials [7]. Recent updates also emphasize the "3Rs approach" (reduction, refinement, and replacement of animal testing) and provide more detailed requirements for chemical characterization per ISO 10993-18 [2].

Table 1: Key Biological Safety Endpoints per ISO 10993-1

| Endpoint | Description | Examples of Assessment Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Cytotoxicity | Cell damage or death | Direct contact, agar diffusion, extract dilution |

| Sensitization | Allergic reaction | Guinea pig maximization test, local lymph node assay |

| Irritation | Localized inflammatory response | Intracutaneous reactivity, skin irritation tests |

| Systemic Toxicity | Effects on entire organism | Acute, subacute, subchronic toxicity studies |

| Genotoxicity | Damage to genetic material | Ames test, chromosomal aberration assay |

| Carcinogenicity | Cancer-causing potential | Long-term rodent studies, cell transformation |

| Implantation Effects | Local effects after implantation | Histopathological evaluation of implant sites |

Material Considerations for Implantable Bioelectronics

The Shift to Soft and Flexible Materials

Traditional implantable electronics utilizing rigid materials like silicon and metals create mechanical mismatch with soft biological tissues, leading to complications such as microinjury, inflammation, fibrosis, and eventual device failure [1]. This mechanical disparity triggers a foreign body response, where the immune system recognizes the implant as a foreign object, resulting in fibrous encapsulation that isolates the device from target tissue and compromises signal integrity [4]. The field has consequently shifted toward soft, flexible bioelectronic devices that match the mechanical properties of biological tissues.

Table 2: Mechanical Properties Comparison: Traditional vs. Advanced Materials

| Material Category | Example Materials | Young's Modulus | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Rigid Electronics | Silicon, Gold, Polyimide | >1 GPa | Established fabrication, stable performance | Mechanical mismatch causes inflammation |

| Medical Grade Elastomers | BIIR, PDMS, Polyurethane | 1 kPa - 1 MPa | Excellent biocompatibility, shock absorption | May require specialized processing |

| Conducting Polymers | PEDOT:PSS, PANI | 20 kPa - 3 GPa | Mixed ionic-electronic conduction | Potential long-term stability challenges |

| Hydrogels | Alginate, Hyaluronic acid-based | ~10 kPa | Similar modulus to excitable tissues | Limited semiconductor capabilities |

Recent breakthroughs demonstrate this principle through elastomeric organic field-effect transistors made from blends of semiconducting nanofibers and biocompatible elastomers. These composites exhibit mechanical stretchability with similar Young's modulus to human tissues while maintaining stable electrical performance under strain up to 50% [8]. Specifically, devices utilizing bromo isobutyl–isoprene rubber (BIIR) – a medical-grade elastomer meeting stringent biocompatibility standards – combined with semiconducting polymers have demonstrated stable operation in logic circuits under physiological conditions with minimal inflammatory response in vivo [8].

Organic Electronic Materials

Organic electronic materials provide unique advantages for bioelectronic interfaces due to their mechanical compatibility and mixed conduction capabilities. These carbon-based semiconducting materials can be engineered to be flexible, elastic, biodegradable, or biocompatible, enabling seamless integration with biological systems [3]. Their fundamental advantage lies in capacity for mixed conduction – facilitating transport of both electrons and ions – which is crucial for interfacing with biological systems where communication typically occurs through ionic mechanisms [4].

Conductive polymers like Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT:PSS) have demonstrated particular promise, creating nerve interfaces that remained stable for over 7 months in vivo [4]. These materials can be processed using low-cost techniques like inkjet printing, spray coating, and spin coating, enabling fabrication of ultra-thin, lightweight devices that can be seamlessly integrated with biological tissues [3].

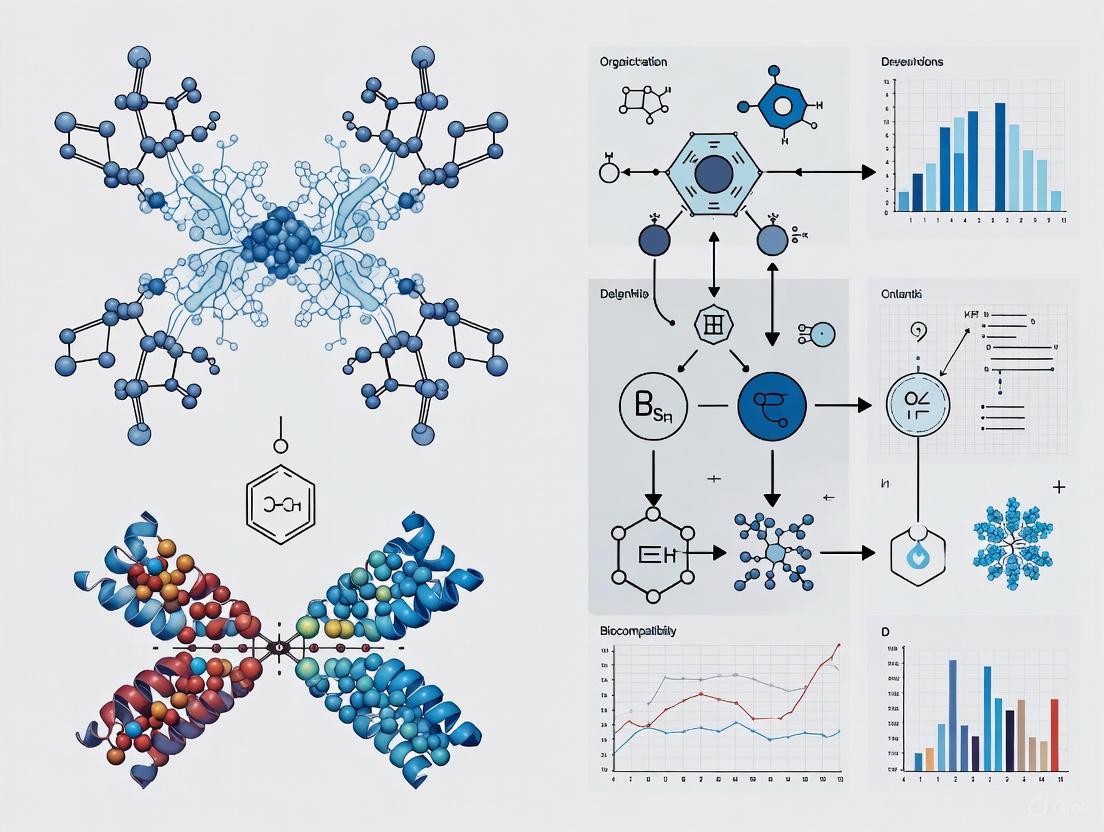

Figure 1: Property-to-Function Relationship in Organic Bioelectronic Materials

Testing Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

ISO 10993 Biocompatibility Testing Framework

The biological evaluation of medical devices follows a structured approach outlined in ISO 10993, requiring different tests based on the nature and duration of body contact. For implantable bioelectronics, which typically fall under "externally communicating" or "implant" devices with prolonged or long-term contact duration, a comprehensive testing strategy is essential [2].

The evaluation process begins with chemical characterization per ISO 10993-18, which identifies and quantifies constituent materials and extractable substances. This is followed by a battery of tests assessing various biological endpoints:

In vitro cytotoxicity tests (ISO 10993-5): Determine if device materials contain harmful extractables that cause cell death or damage. Common assays include mitochondrial dehydrogenase performance measurement (MTT assay), XTT cell proliferation assay, and neutral red uptake cytotoxic assay [4].

Sensitization and irritation tests (ISO 10993-10): Evaluate potential for allergic contact dermatitis and localized inflammatory responses.

Systemic toxicity assays (ISO 10993-11): Assess effects on entire organism through acute, subacute, subchronic, and chronic toxicity studies.

Genotoxicity tests (ISO 10993-3): Screen for damage to genetic material using bacterial reverse mutation tests (Ames test) and mammalian cell chromosomal aberration assays.

Implantation studies (ISO 10993-6): Evaluate local effects after implantation in living tissue, typically assessed through histopathological evaluation of implant sites after explanation.

Figure 2: Biological Evaluation Workflow for Implantable Bioelectronics

Advanced Testing Protocols for Bioelectronics

Beyond standard ISO testing, implantable bioelectronics require specialized evaluations addressing their unique functional requirements:

Electrical Performance in Physiological Environments: Assessing maintained functionality during continuous exposure to biofluids. This includes evaluating insulation resistance, electrode impedance, and stimulus efficacy after accelerated aging in simulated physiological solutions [1].

Mechanical Reliability Under Dynamic Strain: Testing operational stability during repeated mechanical deformation mimicking body movements. For neural interfaces, this includes assessing signal fidelity during cyclic bending and stretching [8].

Long-term Biostability: Evaluating material degradation and foreign body response over extended implantation periods. Advanced protocols include multimodal characterization of explanted devices using electron microscopy, spectroscopic analysis, and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy [4].

Functional Integration with Neural Tissue: Assessing device-tissue integration through immunohistochemical analysis of neuronal and glial markers at the interface, quantifying neuronal density, astrocyte activation, and microglial response [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bioelectronics Biocompatibility Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| BIIR (Bromo Isobutyl–Isoprene Rubber) | Medical-grade elastomer matrix | Provides biocompatibility and mechanical flexibility in semiconductor blends [8] |

| PEDOT:PSS | Conductive polymer with mixed conduction | Neural interface electrodes, transistor channels [4] |

| DPPT-TT Semiconductor | Donor-acceptor semiconducting polymer | Creates stretchable semiconducting nanofiber networks [8] |

| Poly-l-lysine | Positively charged adhesion promoter | Enhances cell adhesion to hydrophobic semiconductor surfaces [4] |

| Sulfur Vulcanization System | Chemical crosslinking of elastomers | Enhances mechanical properties of rubber-based semiconductors [8] |

| Dual-layer Ag/Au Metallization | Stretchable, corrosion-resistant electrodes | Maintains conductivity in biofluid environments [8] |

| JTE-952 | JTE-952, MF:C30H34N2O6, MW:518.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Enpp-1-IN-26 | Enpp-1-IN-26, MF:C16H12FN5O2S, MW:357.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Emerging Technologies and Clinical Translation

Innovative Bioelectronic Platforms

Recent technological advances have produced increasingly sophisticated bioelectronic platforms with enhanced biocompatibility:

Circulatronics: MIT researchers have developed microscopic wireless electronic devices that travel through blood vessels and autonomously self-implant in target brain regions. These cell-electronics hybrids fuse the versatility of electronics with biological transport capabilities of living cells, enabling implantation without invasive surgery and without triggering immune rejection [9].

Soft, Injectable Electronics: Ultra-flexible mesh electronics capable of injection into target tissues with minimal damage, creating stable long-term interfaces with neurons without chronic immune response [1].

Bioresorbable Electronics: Temporary devices that dissolve after a prescribed operational period, eliminating need for surgical extraction. These systems maintain functionality during treatment timelines then safely resorb [1].

Clinical Outcomes and Performance Metrics

The ultimate validation of biocompatibility comes from clinical performance. Successful implantable bioelectronics demonstrate:

Stable Long-term Function: Devices like poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) neural interfaces have maintained functionality for over 7 months in vivo without significant signal degradation [4].

Minimal Foreign Body Response: Advanced materials showing reduced fibrotic encapsulation, with histopathological analysis revealing integration within neural tissue without significant glial scarring [8].

Preserved Tissue Integrity: Biocompatible elastomeric transistors show no adverse effects on cell viability, proliferation, or migration in vitro, and no major inflammatory response or tissue damage in vivo [8].

Challenges in Reliability and Stability

Despite significant advances, long-term reliability of implantable bioelectronics remains challenging. Key failure modes include:

Water Permeation and Encapsulation Failure: Degradation of barrier layers allowing biofluid penetration and device corrosion [1].

Mechanical Fatigue at Interconnects: Stress concentration points between materials with different mechanical properties leading to circuit failure [1].

Biofouling and Impedance Changes: Protein adsorption and cellular attachment on electrode surfaces altering interface properties and signal fidelity [4].

Foreign Body Response Evolution: Chronic inflammatory response continuing beyond initial implantation phase, leading to progressive signal degradation [1].

Defining biocompatibility for implantable bioelectronics requires a multidimensional approach spanning regulatory standards, material science, biological testing, and clinical validation. The evolving ISO 10993-1:2025 framework emphasizes integration with risk management processes throughout the device lifecycle, while advances in organic bioelectronic materials enable increasingly seamless tissue-device interfaces. The field continues to progress toward softer, more compliant materials that minimize mechanical mismatch, sophisticated surface modifications that direct favorable biological responses, and comprehensive testing strategies that predict long-term performance. As these technologies advance toward broader clinical adoption, maintaining focus on fundamental biocompatibility principles will ensure new bioelectronic therapies achieve their potential to transform treatment of neurological disorders, chronic diseases, and other challenging conditions while ensuring patient safety and device efficacy.

The development of advanced bioelectronic interfaces for healthcare monitoring, diagnostics, and therapeutics represents one of the most promising frontiers in medical science. However, a fundamental challenge persists: the significant mechanical mismatch between conventional electronic materials and the soft, dynamic tissues of the human body. This disparity in mechanical properties—particularly Young's modulus, which quantifies material stiffness—creates substantial barriers to effective biointegration. Traditional inorganic electronic materials, such as silicon and metals, possess moduli in the gigapascal (GPa) range, making them orders of magnitude stiffer than biological tissues, which typically exhibit moduli in the kilopascal (kPa) range [10] [3]. This mechanical incompatibility leads to interfacial stress, tissue damage, chronic inflammation, and ultimately device failure [8] [1].

The field has consequently pivoted toward soft organic materials—including conductive polymers, elastomers, and hydrogels—that can closely mimic the mechanical properties of biological tissues. These materials form the foundation of organic bioelectronics, an interdisciplinary field leveraging carbon-based semiconductors to create seamless interfaces with biological systems [11] [3]. This technical analysis examines the core of the mechanical mismatch problem, contrasting the properties and biological impacts of rigid inorganic versus soft organic materials within the context of biocompatibility research. By synthesizing recent advances in materials science and device engineering, this review provides a framework for developing next-generation bioelectronic systems that achieve mechanical harmony with living tissues.

Quantitative Analysis of Material Properties

The mechanical mismatch between bioelectronic interfaces and biological tissues can be quantitatively assessed through several key parameters, with Young's modulus being the most critical for predicting biocompatibility and long-term integration.

Table 1: Mechanical Properties of Biological Tissues and Electronic Materials

| Material Category | Example Materials | Young's Modulus | Tensile Strain (%) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Tissues | Brain Tissue | 1 - 4 kPa [12] | N/A | Soft, viscoelastic, aqueous |

| Myocardial Tissue | 10 - 15 kPa [10] | N/A | Dynamic, continuously moving | |

| Skin | 100 kPa - 1 MPa [13] [3] | N/A | Multilayered, protective | |

| Rigid Inorganic Materials | Silicon (Bulk) | ~100 GPa [10] | <1% [1] | Brittle, high processing temperature |

| Gold (Au) | 20 - 80 GPa [3] | <5% [1] | Ductile but stiff, corrosion-resistant | |

| Silicon Dioxide (SiOâ‚‚) | ~70 GPa [10] | <1% | Excellent insulator, chemically stable | |

| Soft Organic Materials | PEDOT:PSS (Pure Film) | 1 - 2 GPa [12] | ~2% [12] | Conductivity-mechanical trade-off |

| PEDOT:PSS Hydrogels | 0.1 - 1 MPa [13] | >20% | Tissue-like, mixed ionic-electronic conduction | |

| Biocompatible Elastomers (e.g., BIIR) | ~100 kPa [8] | Up to 100% [8] | Medical-grade, high elasticity | |

| Conductive Hydrogels (PEDOT:DBSA) | <1 MPa [13] | Tunable | High water content, excellent biocompatibility |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Rigid vs. Soft Bioelectronics

| Property | Rigid Bioelectronics | Soft and Flexible Bioelectronics |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Material Types | Silicon, metals, ceramics | Polymers, elastomers, hydrogels |

| Young's Modulus Range | >1 GPa [1] | 1 kPa - 1 MPa [1] |

| Bending Stiffness | >10â»â¶ Nm [1] | <10â»â¹ Nm [1] |

| Stretchability | <1% (brittle) [1] | >10% (>100% for ultra-soft) [1] |

| Tissue Integration | Stiffness mismatch causes inflammation and fibrotic encapsulation [1] | Matches tissue mechanics, reduces immune response [1] |

| Signal Fidelity | Strong short-term signal quality [1] | Better chronic signal due to stable tissue contact [1] |

| Long-term Stability | Long-term degradation due to micromotion and scar tissue [1] | Can degrade due to soft substrate fatigue [1] |

The quantitative data reveals the profound mechanical disparity that exists at the bioelectronic interface. The modulus of silicon is approximately 10 million times stiffer than that of brain tissue, creating a significant mechanical gradient that the body perceives as a foreign object [12]. This mismatch triggers a cascade of biological responses, beginning with protein adsorption and culminating in the formation of a fibrotic capsule around the implant, which electrically isolates the device and degrades its performance over time [10].

In contrast, soft organic materials bridge this mechanical divide. Advanced material systems, such as the vulcanized blend of DPPT-TT and bromo isobutyl-isoprene rubber (BIIR) reported by [8], achieve both semiconducting functionality and mechanical compatibility. This particular composite exhibits a Young's modulus similar to human tissues and maintains stable electrical performance even under 50% strain, representing a significant advancement toward truly biocompatible electronics [8].

The Biological Impact of Mechanical Mismatch

Foreign Body Response and Fibrotic Encapsulation

The implantation of any medical device triggers a complex biological sequence known as the foreign body response (FBR). While this process is inevitable, its severity is directly influenced by the mechanical properties of the implanted material. Rigid implants with high modulus mismatch cause sustained mechanical irritation at the tissue interface, amplifying the FBR and leading to the formation of a dense collagenous capsule that can be hundreds of micrometers thick [10] [1]. This fibrotic tissue acts as an electrical insulator, diminishing signal quality in recording applications and increasing impedance in stimulation devices. Studies have shown that the chronic inflammatory response to stiff implants can persist for the entire duration of implantation, continuously degrading the interface and ultimately leading to device failure [10].

Tissue Damage and Signal Integrity

Beyond chronic inflammation, the acute mechanical mismatch between rigid devices and soft tissues can cause direct physical damage during implantation and normal physiological motion. The brain, for instance, exhibits micromotion due to cardiovascular and respiratory cycles, creating repeated shear forces at the interface with rigid implants [12]. This results in progressive tissue damage, neuronal death, and glial scarring, which compromises the very cellular populations that neural interfaces aim to monitor or stimulate. The resulting signal degradation manifests as decreased signal-to-noise ratio, increased instability, and eventual loss of functional recording or stimulation capability [1] [12].

Organic Materials as a Solution to Mechanical Mismatch

Conductive Polymers and Their Composites

Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):polystyrenesulfonate (PEDOT:PSS) has emerged as a cornerstone material in organic bioelectronics due to its combination of high electrical conductivity, environmental stability, and tunable mechanical properties [12]. When processed as a pure film, PEDOT:PSS still exhibits a relatively high modulus (~1-2 GPa), but through various formulation strategies—including the addition of plasticizers, secondary dopants, and blending with elastomers—its mechanical properties can be engineered to better match biological tissues [12].

Recent innovations have produced PEDOT:PSS-based hydrogels that achieve conductivities up to 5 × 10³ S/m while maintaining moduli in the MPa range, significantly closer to tissue values [13] [12]. Alternative formulations, such as PEDOT:DBSA hydrogels, offer improved biocompatibility by eliminating the potentially cytotoxic PSS component while maintaining tissue-like mechanical properties (Young's modulus <1 MPa) and sufficient conductivity for bioelectronic applications [13].

Elastomer-Semiconductor Composites for Intrinsic Stretchability

Beyond conductivity matching, the next frontier in biocompatible interfaces involves creating devices with intrinsic stretchability to accommodate tissue dynamics. Pioneering work by [8] demonstrates a biocompatible elastomeric organic transistor using a blend of semiconducting nanofibers (DPPT-TT) and a medical-grade elastomer (BIIR). This composite system exhibits several critical advantages:

- High mechanical stretchability (up to 100% strain without cracking)

- Biocompatibility confirmed through in vitro and in vivo studies

- Stable electrical performance under physiological conditions

- Similar Young's modulus to human tissues [8]

The vulcanization process used in fabricating these devices selectively crosslinks the elastomer matrix while preserving the conjugated structure of the semiconductor, enabling both mechanical robustness and electronic functionality [8]. This approach represents a significant advancement over earlier stretchable electronics that used non-biocompatible elastomers like PDMS, which could induce chronic foreign body reactions despite their favorable mechanical properties [8].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Mechanical Compatibility

In Vitro Biocompatibility Testing

Rigorous assessment of new bioelectronic materials requires standardized in vitro protocols to evaluate cellular responses prior to in vivo implantation.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Biocompatibility Testing

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Human Dermal Fibroblasts | Model cell type for assessing cytotoxicity | In vitro biocompatibility testing [8] |

| Macrophages | Model immune response to implants | In vitro inflammatory response assessment [8] |

| Cell Viability Assays | Quantify live/dead cell ratios | Determine material cytotoxicity [8] |

| Proliferation/Migration Assays | Assess impact on cellular function | Evaluate long-term biocompatibility [8] |

| Murine Endothelial Cells | Model vascular interface compatibility | Test blood-contacting devices [13] |

Protocol: Cytocompatibility Assessment of Conductive Hydrogels

Material Preparation: Formulate hydrogel samples under sterile conditions. For PEDOT:DBSA hydrogels, this involves mixing the polymer dispersion with DBSA (3-10 v/v%) at room temperature until homogenized, followed by centrifugation to separate microgels [13].

Cell Seeding: Plate relevant cell types (e.g., human dermal fibroblasts, murine endothelial cells) in standard culture plates at appropriate densities (typically 10,000-50,000 cells/cm²).

Material Exposure: Apply sterile material extracts or place direct material contacts onto established cell monolayers. For direct contact tests, use material discs with standardized surface area-to-volume ratios.

Viability Assessment: After 24-72 hours of exposure, perform viability assays (e.g., Live/Dead staining, MTT, Alamar Blue) according to manufacturer protocols. Calculate viability percentages relative to negative controls.

Proliferation and Migration Analysis: Quantify cell proliferation rates over 3-7 days using DNA content assays or direct cell counting. Assess migration through scratch/wound healing assays, measuring closure rates over 24-48 hours [8] [13].

In Vivo Implantation Studies

Long-term biocompatibility and mechanical integration must be evaluated in living organisms to account for the full complexity of the foreign body response.

Protocol: In Vivo Evaluation of Soft Bioelectronic Implants

Device Fabrication: Fabricate test devices using the target material system. For elastomeric transistors, this involves creating blend films of semiconductor and elastomer (e.g., DPPT-TT:BIIR at 3:7 ratio), followed by vulcanization with sulfur-based crosslinkers [8].

Surgical Implantation: Under approved animal protocol guidelines, implant devices in target tissues (e.g., subcutaneous, neural, or cardiac) using aseptic surgical techniques. Include appropriate controls (sham surgery, commercially available materials).

Histological Analysis: After predetermined intervals (e.g., 2, 4, 12 weeks), euthanize animals and harvest implant sites with surrounding tissues. Process for histological sectioning and staining (H&E for general morphology, Masson's Trichrome for collagen deposition, immunohistochemistry for specific cell types).

Inflammatory Response Quantification: Score histological sections for key indicators of the foreign body response: inflammatory cell density (neutrophils, macrophages), fibrotic capsule thickness, and tissue integration quality. Compare experimental groups to controls [8].

Functional Stability Assessment: For active electronic devices, monitor electrical performance (impedance, signal-to-noise ratio, stimulation efficacy) throughout the implantation period to correlate mechanical integration with functional stability [8] [12].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for evaluating mechanical compatibility of bioelectronic materials, integrating both in vitro and in vivo assessments to ensure comprehensive biocompatibility validation.

Emerging Strategies and Future Directions

Multimodal Integration and Closed-Loop Systems

The convergence of soft bioelectronics with artificial intelligence is enabling a new generation of closed-loop bioelectronic systems that can adaptively respond to physiological states. These systems leverage conformable interfaces to acquire high-fidelity signals, process them using machine learning algorithms, and deliver precise therapeutic interventions—all while maintaining mechanical harmony with tissues [14] [15]. Such integrated platforms represent the future of bioelectronic medicine, transitioning from static implants to dynamic systems that can evolve with patient needs.

Advanced Manufacturing and Minimally Invasive Deployment

Sophisticated fabrication techniques are critical for realizing the full potential of soft bioelectronic materials. 3D printing technologies enable the creation of complex, customized architectures from conductive polymer hydrogels, allowing for patient-specific interface designs [12]. Simultaneously, the development of injectable bioelectronics—including flexible mesh electrodes and hydrogel-based devices that can be delivered through syringe injection—promises to minimize surgical trauma and improve patient outcomes [10] [1] [15]. These deployment strategies are particularly valuable for interfacing with delicate tissues like the brain, where minimizing insertion damage is paramount for long-term functionality.

The mechanical mismatch between traditional rigid electronics and soft biological tissues represents a fundamental barrier in bioelectronic medicine. Through the strategic development and implementation of soft organic materials—including conductive polymers, elastomeric composites, and hydrogels—the field is making significant progress toward seamless bioelectronic interfaces. These advanced materials systems demonstrate that achieving mechanical harmony with biological tissues is not merely a desirable feature but an essential requirement for chronic device functionality and biocompatibility.

As research progresses, the integration of these soft materials with sophisticated manufacturing techniques and intelligent control systems will enable a new paradigm in bioelectronic medicine. The future of the field lies in creating devices that not only match the mechanical properties of tissues but also adapt to their dynamic nature, ultimately forming stable, long-lasting interfaces that can transform our approach to diagnosing and treating disease.

The emergence of organic bioelectronics represents a paradigm shift in the development of medical devices, enabling seamless integration of electronic components with biological systems. This field leverages the unique properties of organic electronic materials to create devices that can successfully interface with the electrically active tissues of the human body [16]. The fundamental challenge in bioelectronic medicine has been the mechanical and chemical mismatch between conventional rigid electronic components and soft, dynamic biological tissues, which often leads to tissue damage, inflammation, and device failure over time [8] [17]. Overcoming this challenge requires the strategic engineering of three core material properties: biocompatibility to ensure safe biological interactions, stretchability to achieve mechanical compatibility with soft tissues, and mixed ionic-electronic conduction to facilitate seamless communication between electronic devices and ionic biological systems [16] [18]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of these key properties, their interrelationships, measurement methodologies, and their critical role in advancing organic bioelectronics for therapeutic applications, framed within the context of biocompatibility research for next-generation medical devices.

Fundamental Properties in Organic Bioelectronics

Biocompatibility

Biocompatibility extends beyond simple non-toxicity to encompass the ability of a material to perform with an appropriate host response in a specific application [17]. For implantable bioelectronic devices, this property is paramount as it determines the long-term viability and safety of the device-tissue interface. The biocompatibility of organic electronic materials derives from their molecular structure, surface chemistry, and mechanical properties, which collectively influence protein adsorption, cellular adhesion, and immune responses [16].

Recent advances have demonstrated that medical-grade elastomers such as bromo isobutyl–isoprene rubber (BIIR) meet stringent biocompatibility standards set by regulatory bodies (ISO 10993, European Pharmacopoeia) and exhibit excellent mechanical properties including shock absorption, aging resistance, and high physical strength [8]. These materials show minimal adverse effects on cell viability, proliferation, and migration in vitro, and elicit no major inflammatory response or tissue damage in vivo, as confirmed by implantation studies in animal models [8].

Table 1: Biocompatibility Assessment Parameters and Methods

| Assessment Parameter | Experimental Methodology | Key Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular Response | In vitro co-culture with human dermal fibroblasts and macrophages | Cell viability, proliferation rates, migration patterns |

| Immune Response | In vivo implantation studies (e.g., mouse model) | Inflammatory markers, fibrosis, tissue damage assessment |

| Long-term Stability | Accelerated aging tests in simulated physiological conditions | Material degradation rates, leachable compounds analysis |

| Systemic Toxicity | ISO 10993 standard testing | Hematological parameters, organ histopathology |

Stretchability

Stretchability refers to a material's ability to undergo mechanical deformation (bending, twisting, stretching) while maintaining its structural integrity and electronic functionality [16]. This property is crucial for bioelectronic devices that need to conform to dynamic biological surfaces such as beating hearts, contracting muscles, or moving joints [8]. The mechanical mismatch between conventional rigid electronics (Young's modulus in GPa range) and soft biological tissues (Young's modulus in kPa to MPa range) can lead to tissue damage, inflammation, and device failure [16] [8].

Advanced material designs have achieved remarkable stretchability through innovative approaches such as semiconducting nanofiber networks embedded within elastomer matrices. For instance, composite films of poly[(dithiophene)-alt-(2,5-bis(2-octyldodecyl)-3,6-bis(thienyl)-diketopyrrolopyrrole)] (DPPT-TT) and BIIR can sustain up to 100% strain without mechanical damage and maintain stable electrical performance under 50% strain [8]. These stretchable organic field-effect transistors (sOFETs) demonstrate stable operation in logic circuits (inverters, NOR gates, NAND gates) even under physiological conditions, making them suitable for implantable applications [8].

Table 2: Mechanical Properties of Bioelectronic Materials vs. Biological Tissues

| Material/Tissue | Young's Modulus | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional Silicon | 100-200 GPa | Rigid, brittle, significant mechanical mismatch |

| Gold Electrodes | 50-80 GPa | High conductivity but stiff |

| Polyimide (PI) | 2-3 GPa | Flexible but relatively high modulus |

| Conducting Polymers (PEDOT:PSS) | 1 MPa - 2 GPa | Tunable mechanical properties |

| Elastomers (PDMS, PU) | 0.1-3 MPa | Soft, stretchable, tissue-compatible |

| Human Tissues (Brain, Heart, PNS) | 0.1-100 kPa | Soft, hydrated, viscoelastic |

Mixed Ionic-Electronic Conduction

Organic mixed ionic-electronic conductors (OMIECs) represent a specialized class of materials capable of transporting both electronic charge carriers (electrons and holes) and ionic species (Na+, K+, Cl-, etc.) simultaneously [18]. This dual conduction mechanism is particularly advantageous for bioelectronics applications where efficient translation between electronic signals in devices and ionic signals in biological systems is required [16] [18]. The performance and operational stability of OMIECs in aqueous environments are influenced by dynamic interactions between polymer functionalities and electrolyte species [18].

Key OMIECs such as poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT:PSS) and various polyaniline (PANI) derivatives demonstrate excellent mixed conduction properties, making them ideal for organic electrochemical transistors (OECTs) [16]. The molecular design of these materials, particularly sidechain engineering, significantly impacts ion transport, hydration, swelling behavior, and mixed conduction properties [18]. For instance, ethylene glycol-based sidechains and emerging hybrid designs incorporating ionic moieties can tune material-electrolyte interactions, affecting doping mechanisms and structural stability [18].

Interrelationship of Key Properties

The three core properties—biocompatibility, stretchability, and mixed ionic-electronic conduction—are not independent but exhibit strong interdependencies that must be considered in material design. The relationship between these properties forms the foundation for high-performance bioelectronic devices.

Diagram 1: Property Interrelationships in Bioelectronic Materials

The interconnected nature of these properties creates both challenges and opportunities in material design. For instance, achieving mixed ionic-electronic conduction often requires hydrophilic components that facilitate ion transport, but these same components may swell excessively in physiological environments, compromising mechanical stability and potentially triggering adverse biological responses [18]. Similarly, enhancing stretchability through elastomeric blending must be balanced against potential impacts on electrical performance and biocompatibility [8]. Understanding these complex interrelationships enables the rational design of materials optimized for specific bioelectronic applications.

Experimental Protocols and Characterization Methods

Synthesis of Stretchable Biocompatible Semiconductors

The development of high-performance stretchable semiconductors employs sophisticated material processing techniques. A representative protocol for creating biocompatible stretchable transistors involves:

Material Preparation: Prepare a blend solution of semiconducting polymer (e.g., DPPT-TT) and medical-grade elastomer (e.g., BIIR) in appropriate organic solvents. Optimal electrical and mechanical properties are typically achieved at a 3:7 weight ratio of DPPT-TT to BIIR [8].

Vulcanization Process: Add vulcanizing agents including sulfur (crosslinker), dipentamethylenethiuram tetrasulfide (DPTT, accelerator), and stearic acid (initiator) to the blend solution. The vulcanization process involves three stages: initiation for radical formation, propagation for crosslinking BIIR with sulfur, and termination for reaction completion [8].

Film Fabrication: Deposit the vulcanized blend solution onto substrates using spin-coating, blade-coating, or printing techniques. Achieve uniform film thickness between 100-500 nm for optimal electronic and mechanical performance.

Characterization: Validate successful vulcanization through Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) by monitoring reduction in C–Br peaks (667 cm−1) and C=C peaks (1,538 cm−1) in neat BIIR post-vulcanization [8].

This protocol yields a composite film with semiconducting nanofiber networks embedded within an elastomer matrix, exhibiting high mechanical stretchability (up to 100% strain), biocompatibility, and stable electrical performance under deformation [8].

Biocompatibility Assessment Workflow

Rigorous biocompatibility assessment follows a structured workflow to evaluate material safety for biomedical applications.

Diagram 2: Biocompatibility Assessment Workflow

This comprehensive assessment approach ensures that bioelectronic materials meet the stringent safety requirements for clinical applications. The in vitro phase typically involves co-culture studies with relevant cell lines (e.g., human dermal fibroblasts and macrophages) to assess cytotoxicity, while in vivo studies evaluate the host response to implanted materials over extended periods [8]. Materials showing favorable performance in these assessments can proceed to regulatory validation following established standards such as ISO 10993 [8].

Electrical Performance Under Strain

Characterizing the electrical properties of bioelectronic materials under mechanical deformation requires specialized measurement techniques:

Strain-Dependent Electrical Measurements: Mount stretchable semiconductor films on custom strain jigs capable of applying precise mechanical deformation (0-100% strain). Measure field-effect mobility, ON/OFF ratio, and threshold voltage at various strain levels using semiconductor parameter analyzers [8].

Cyclic Stretch Testing: Subject devices to repeated stretching cycles (e.g., 1,000 cycles at 100% strain) to evaluate mechanical durability and electrical stability under physiological-like conditions [8].

Operando Characterization: Employ advanced operando techniques including conductive atomic force microscopy (C-AFM) to monitor nanoscale morphological changes and charge transport under applied strain. This reveals the alignment of semiconducting nanofibers along the strain direction, which provides strain-insensitive conductive pathways [8].

These methodologies demonstrate that optimized stretchable semiconductors can maintain stable field-effect mobility (>1 cm²/V·s) even under 50% strain and after thousands of stretching cycles, satisfying the requirements for implantable bioelectronic applications [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Advancing research in organic bioelectronics requires access to specialized materials and characterization tools. The following table outlines essential components of the research toolkit for investigating biocompatibility, stretchability, and mixed conduction.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Organic Bioelectronics

| Material/Reagent | Function and Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS | Benchmark organic mixed conductor for OECTs and electrodes | High conductivity, tunable mechanical properties, commercial availability |

| DPPT-TT Semiconductor | High-performance semiconducting polymer for stretchable OFETs | Donor-acceptor structure, field-effect mobility, processability |

| BIIR Elastomer | Biocompatible elastomer matrix for medical devices | ISO 10993 certification, mechanical robustness, chemical resistance |

| Medical-Grade PDMS | Flexible substrate and encapsulation material | Transparency, biocompatibility, tunable modulus |

| Ag/Au Dual-Layer Metallization | Stretchable, corrosion-resistant electrodes for implants | Ag for conductivity, Au for biofluid resistance, stretchable design |

| Vulcanization Agents | Crosslinking system for enhancing mechanical properties | Sulfur (crosslinker), DPTT (accelerator), stearic acid (initiator) |

| Ferolin | Ferolin, MF:C22H30O4, MW:358.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Luteolin 7-O-glucuronide | Luteolin 7-O-glucuronide, MF:C21H17O12-, MW:461.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

This toolkit provides the foundation for developing and characterizing advanced bioelectronic materials. The selection of appropriate materials must consider the specific application requirements, including the intended implantation site, duration of use, and necessary signal transduction mechanisms.

The convergence of biocompatibility, stretchability, and mixed ionic-electronic conduction represents the cornerstone of next-generation organic bioelectronics. These interdependent properties enable the creation of devices that can seamlessly integrate with biological systems, providing stable long-term interfaces for monitoring and modulating physiological activity. Advances in material design, particularly the development of nanostructured composites and sophisticated molecular engineering approaches, have yielded significant progress in achieving this combination of properties in functional devices. The ongoing refinement of characterization methodologies and the establishment of comprehensive biocompatibility assessment protocols continue to drive the field toward clinical translation. As research in this area advances, the strategic integration of these three fundamental properties will unlock new possibilities in personalized medicine, neural interfaces, and implantable therapeutic devices, ultimately transforming the landscape of healthcare and human-machine integration.

Organic bioelectronics represents a transformative frontier in medical science, enabling the development of devices that seamlessly integrate with biological systems for monitoring, diagnostics, and therapeutics. This field leverages carbon-based semiconductors and elastomeric polymers to create interfaces that overcome the limitations of traditional rigid electronics, particularly the mechanical mismatch with soft biological tissues. The convergence of these materials has catalyzed advancements in implantable sensors, neural interfaces, and wearable health monitors.

This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical analysis of three pivotal materials in organic bioelectronics: the conducting polymer PEDOT:PSS, the semiconducting polymer DPPT-TT, and the medical-grade elastomer bromo isobutyl-isoprene rubber (BIIR). We examine their fundamental properties, processing techniques, and performance characteristics within the critical framework of biocompatibility research, addressing both current applications and future potential for clinical translation.

Material Properties and Characteristics

PEDOT:PSS (Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):Poly(Styrene Sulfonate))

PEDOT:PSS is a conductive polymer complex consisting of a conjugated, positively-charged PEDOT backbone and an insulating, negatively-charged PSS polyelectrolyte. This structure forms a colloidal dispersion in water, where PSS stabilizes the otherwise insoluble PEDOT through electrostatic interactions [19] [12]. The material is commercially available as an aqueous dispersion or powder from suppliers such as Heraeus Holding GmbH (Clevios) and Agfa-Gevaert N.V. (Orgacon) [19].

Table 1: Key Properties of PEDOT:PSS

| Property | Typical Range/Value | Notes and Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Conductivity | < 1 to ~300 S/cm [19] [12] | Highly tunable; pristine form is at lower end, can be enhanced with secondary doping [12] |

| Mechanical Properties | Young's Modulus: 1-2 GPa [12] | Relatively rigid in pure form; can be plasticized or formulated into hydrogels for softness |

| Stretchability | ~2% elastic strain (pristine) [12] | |

| Optical Transparency | High in thin films [19] | Suitable for transparent electrode applications |

| Biocompatibility | Good [19] [12] | Considered biocompatible; essential for bioelectronic interfaces |

| Primary Bioelectronic Use | Electrodes, sensors, OECTs [19] [12] | Used as thin films, coatings, or scaffolds |

DPPT-TT (Poly[(dithiophene)-alt-(2,5-bis(2-octyldodecyl)-3,6-bis(thienyl)-diketopyrrolopyrrole)])

DPPT-TT is a donor-acceptor (D-A) type semiconducting polymer known for its high charge-carrier mobility. Its structure features electron-deficient diketopyrrolopyrrole (DPP) and electron-rich dithiophene (TT) units, which promote strong π-π stacking and efficient charge transport [8] [20]. It is typically processed from organic solvents and forms semi-crystalline films.

Table 2: Key Properties of DPPT-TT

| Property | Typical Range/Value | Notes and Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Field-Effect Mobility | High performance in OFETs | Maintains performance when blended with elastomers like BIIR [8] |

| Mechanical Properties | Intrinsically rigid/semi-crystalline | Becomes stretchable when blended into an elastomer matrix (e.g., BIIR) [8] |

| Stretchability | Low in neat form; >100% strain when blended with BIIR (3:7 ratio) [8] | The nanofiber network within the elastomer allows for stretchability without electrical failure |

| Optical Properties | Opaque | Characteristic absorption in the visible to near-infrared region |

| Biocompatibility | Requires encapsulation or blending | Not intrinsically biocompatible; made biocompatible through integration with medical-grade matrices [8] |

| Primary Bioelectronic Use | Active channel in stretchable OFETs [8] [20] | For logic circuits and signal processing in implantable devices |

Medical-Grade BIIR (Bromo Isobutyl-Isoprene Rubber)

BIIR is a medical-grade elastomer that meets stringent ISO 10993 biocompatibility standards, making it suitable for long-term implantation [8]. It can be cross-linked through a vulcanization process, which enhances its mechanical properties and stability. Its primary role in bioelectronics is to serve as a compliant, biocompatible matrix for semiconducting polymers.

Table 3: Key Properties of Medical-Grade BIIR

| Property | Typical Range/Value | Notes and Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Young's Modulus | ~10^7.7 to 10^8.8 Pa [8] | Similar to human tissues, minimizing mechanical mismatch |

| Biocompatibility | High; certified to ISO 10993 [8] | Shows no adverse effects on cell viability, proliferation, or migration in vitro [8] |

| Key Features | Aging resistance, high physical strength, low permeability, chemical resistance [8] | Ideal for chronic implants |

| Primary Bioelectronic Use | Elastomer matrix in stretchable semiconductor composites [8] | Provides mechanical stretchability and biocompatibility to otherwise rigid semiconductors |

Fabrication and Processing Methodologies

Processing Techniques for PEDOT:PSS

The water dispersibility of PEDOT:PSS allows for a variety of solution-processing techniques, which are crucial for fabricating thin films and patterns on diverse substrates.

- Spin-Coating: This method produces uniform, nanoscale thin films ideal for research and small-scale applications. The process involves depositing a droplet of PEDOT:PSS dispersion onto a substrate, which is then rotated at high speed. The centrifugal force spreads the solution into a homogeneous film, with thickness controlled by spin speed and solution viscosity. A key drawback is significant material waste [19].

- Printing Techniques: Inkjet printing and screen printing are direct-write technologies that enable patterned deposition. Inkjet printing precisely dispenses microdroplets through fine nozzles, while screen printing forces ink through a stencil onto a predefined pattern. These techniques are scalable and minimize ink wastage, making them attractive for large-area, patterned electrode fabrication [19].

- Spray Coating: This cost-effective technique is suitable for coating large or irregular surfaces. The PEDOT:PSS solution is aerosolized and sprayed onto a substrate from a nozzle. It results in smooth coatings, though surface wettability and adhesion can be challenges common to all coating methods [19].

- Post-Processing/Annealing: Control over the solvent evaporation rate via annealing (temperature, time, humidity) is critical for forming a homogeneous film from the randomly oriented PEDOT crystals and PSS chains in the dispersion [19].

Creating Stretchable Semiconductors with DPPT-TT and BIIR

The integration of a rigid semiconductor like DPPT-TT with an elastomer like BIIR requires specific processing to achieve a stretchable, electrically functional composite.

- Solution Blending: DPPT-TT and BIIR are co-dissolved in a common organic solvent. The weight ratio is critical; a ratio of 3:7 (DPPT-TT:BIIR) has been optimized to balance electrical performance and mechanical stretchability. At this ratio, the composite film can withstand up to 100% strain without cracking [8].

- Film Formation: The blended solution is deposited onto a substrate via techniques such as spin-coating or blade-coating.

- Vulcanization (Chemical Cross-linking): The deposited film undergoes vulcanization. This process uses sulfur as a crosslinker, dipentamethylenethiuram tetrasulfide (DPTT) as an accelerator, and stearic acid as an initiator [8].

- Initiation: The process begins with radical formation, facilitated by the reduction of C–Br bonds in the BIIR, as confirmed by Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy [8].

- Propagation and Termination: Sulfur crosslinks the BIIR chains, forming a robust, elastic network. FTIR analysis shows a reduction in C=C peaks in neat BIIR, confirming crosslinking. Notably, the C=C conjugated structure of DPPT-TT remains unchanged, preserving its semiconducting capability [8].

This process results in a phase-separated morphology where a percolating network of DPPT-TT nanofibers is embedded within the elastic BIIR matrix. This structure provides a continuous pathway for charge transport while allowing the material to stretch extensively.

Experimental Protocols for Performance and Biocompatibility Evaluation

Electrical Characterization of Stretchable Transistors

The electrical performance of devices like DPPT-TT:BIIR-based stretchable organic field-effect transistors (sOFETs) is characterized using a semiconductor parameter analyzer (e.g., Keysight B1500) [20].

- Transfer Characteristic Measurement: This measures the drain current (ID) as a function of gate voltage (VG) at a constant drain voltage (VD). From this curve, key parameters are extracted:

- Field-Effect Mobility (μ): Calculated in the saturation regime using the equation: ( ID = (W/2L) \mu Ci (VG - V{th})^2 ), where W and L are channel width and length, and Ci is gate dielectric capacitance per unit area.

- Threshold Voltage (V_th): The gate voltage at which the channel begins to conduct.

- Subthreshold Swing (SS): Indicates how sharply the transistor switches on.

- ON/OFF Current Ratio: The ratio between the maximum and minimum drain current.

- Output Characteristic Measurement: This measures ID as a function of VD at different, fixed VG values. The linearity of the curves at low VD is used to extract the on-state resistance (R_on).

- Performance under Strain: These measurements (transfer and output characteristics) are repeated while the transistor is subjected to controlled uniaxial strain (e.g., 0% to 50% or 100%). The stability of mobility and other parameters under strain demonstrates the efficacy of the composite design [8].

Biocompatibility Assessment

Adherence to international standards is paramount for bioelectronic materials. The ISO 10993 series provides a framework for the biological evaluation of medical devices within a risk management process [6].

- In Vitro Cytotoxicity Testing (ISO 10993-5): This is a first-line test to assess the potential for cell death. The protocol involves:

- Sample Preparation: Extracting the material (or a finished device) using both polar and non-polar solvents to simulate the release of leachable chemicals.

- Cell Culture: Exposing mammalian cell lines (e.g., L-929 mouse fibroblasts) to the extracts.

- Viability Assessment: Using a quantitative assay like MTT, which measures mitochondrial activity. A reduction in cell viability by more than 30% is considered a potential cytotoxic effect.

- For the DPPT-TT:BIIR blend, in vitro assessments with human dermal fibroblasts and macrophages showed no adverse effects on cell viability, proliferation, or migration [8].

- In Vivo Implantation Studies: For implantable materials, long-term in vivo studies are essential.

- Animal Model: Devices are implanted in a relevant animal model (e.g., mice or rats).

- Histopathological Analysis: After a predetermined period (e.g., 4, 12, or 26 weeks), the implant site and surrounding tissues are explanted.

- Tissue Staining: The tissue sections are stained (e.g., with Hematoxylin and Eosin) and examined under a microscope for signs of inflammation, fibrosis, and tissue damage.

- For the DPPT-TT:BIIR blend, in vivo implantation studies in mice showed no major inflammatory response or tissue damage [8].

The overall biological evaluation is an iterative process integrated with the device's risk management, as outlined in the updated ISO 10993-1:2025 standard [6] [21].

Visualizing Material Integration and Testing Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the key concepts of composite material structure and the biocompatibility testing workflow.

Diagram 1: Material integration for bioelectronic interfaces. The diagram shows how PEDOT and PSS form a complex via electrostatic bonding, and how DPPT-TT and BIIR are blended and vulcanized to form a stretchable composite. Both systems converge to create a functional bioelectronic interface.

Diagram 2: Biocompatibility testing workflow. The diagram outlines the key stages of evaluating material safety, starting with a risk management plan, progressing through in vitro cytotoxicity tests, and, if passed, moving to in vivo implantation studies. All data is consolidated into a final biological evaluation report.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Bioelectronic Device Fabrication

| Item Name | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS Dispersion | Conductive ink for electrodes, sensors, and OECTs. | Available from Heraeus (Clevios) or Agfa (Orgacon); often requires secondary doping or additive modification for enhanced performance [19] [12]. |

| DPPT-TT Polymer | High-mobility p-type semiconductor for OFETs. | Used as the active channel material; typically blended with elastomers like BIIR for stretchable devices [8] [20]. |

| Medical-Grade BIIR | Biocompatible elastomer matrix. | Provides mechanical compliance and stretchability; crosslinked via vulcanization for enhanced durability [8]. |

| Sulfur & Vulcanization Kit | Crosslinking agents for BIIR. | Includes sulfur (crosslinker), DPTT (accelerator), and stearic acid (initiator) to create a robust elastic network [8]. |

| Dual-Layer Ag/Au Metallization | Biocompatible and corrosion-resistant stretchable electrodes. | Ag provides excellent electrical contact, while an outer Au layer protects against biofluid corrosion [8]. |

| ISO 10993-5 Test Kit | For in vitro cytotoxicity testing. | Includes reagents (e.g., MTT), standardized cell lines (e.g., L-929 fibroblasts), and materials for extract preparation [6] [21]. |

| XEN103 | XEN103, MF:C22H23F4N5O2, MW:465.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| THP104c | THP104c, MF:C20H16N4O2S, MW:376.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Natural polymers represent a cornerstone of modern bioelectronic and biomedical research, offering unparalleled biocompatibility, tunable mechanical properties, and sustainable sourcing. This technical review comprehensively examines three pivotal natural polymers—cellulose, chitosan, and silk fibroin—focusing on their fundamental properties, biocompatibility mechanisms, and applications in advanced bioelectronics and therapeutic platforms. Within the context of organic bioelectronics, we analyze how these materials address the critical challenge of mechanical mismatch between conventional electronic components and soft biological tissues. The review provides detailed experimental protocols for material processing and characterization, visualizes key structure-function relationships through specially formulated diagrams, and presents a curated toolkit of research reagents to facilitate further innovation in this rapidly evolving field.

The integration of biological systems with electronic devices necessitates materials that can seamlessly interface with living tissue without provoking adverse immune responses. Natural polymers have emerged as ideal candidates for this purpose due to their inherent biocompatibility, biodegradability, and structural similarity to native extracellular matrix components. The global market for natural biocompatible polymers is experiencing robust growth, projected to reach $1097.5 million in 2025 with a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 6.8% from 2025 to 2033, reflecting their expanding role in medical technologies [22].

Within the specialized domain of organic bioelectronics, these materials facilitate the development of next-generation implantable devices that overcome the limitations of traditional rigid electronics. This review focuses specifically on cellulose, chitosan, and silk fibroin—three natural polymers with distinct structural and functional properties that make them particularly valuable for biointerfacing applications. We examine their molecular characteristics, biocompatibility metrics, processing methodologies, and implementation in bioelectronic platforms, with particular emphasis on their roles in creating mechanically compliant, physiologically stable interfaces.

Fundamental Properties and Biocompatibility Profiles

Structural Characteristics and Native Properties

Cellulose, the most abundant natural polymer, is a complex carbohydrate consisting of long chains of glucose molecules forming a rigid framework that provides structural support in plants [23]. Its semi-crystalline structure, high tensile strength, biodegradability, and chemical reactivity make it incredibly versatile for biomedical applications. Cellulose is insoluble in water but can be processed into various forms including regenerated cellulose fibers, films, and hydrogels through dissolution and reconstitution methods [24]. The transformation of cellulose chain conformation from cellulose I to cellulose II during regeneration creates structures with more amorphous regions and enhanced crystallinity, facilitating extensive modifications for specific applications [24].

Chitosan, a cationic natural polymer composed of glucosamine and N-acetylglucosamine residues connected by glycosidic bonds, is typically extracted from shrimp and crab shells through demineralization, deproteinization, and deacetylation processes [25]. Its excellent physicochemical properties include stability in natural environments, metal ion chelation, high sorption capacity, and solubility in acidic solutions. Chitosan's chemical structure facilitates remarkable biocompatibility and biodegradability, while its protonated amino groups under acidic conditions confer mucoadhesive properties that promote prolonged contact with biological surfaces and enhanced drug absorption [25].

Silk fibroin (SF), a macromolecular fibrous protein, exhibits irreplaceable value in biomedical applications due to its exceptional mechanical properties, controllable degradability, and unique structure regulation ability [26]. The incorporation of SF into composite materials significantly enhances compressive strength, toughness, and structural stability through the formation of β-sheet crystal structures and intermolecular interactions [26]. This unique structural organization allows SF to address application limitations of traditional biomaterials in tissue engineering, particularly for load-bearing applications.

Biocompatibility and Biological Interactions

Table 1: Biocompatibility Profiles of Natural Polymers

| Polymer | Cytocompatibility Evidence | Immunogenic Response | Regulatory Status | Degradation Profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulose | Excellent biocompatibility with minimal allergic reactions; promotes cell adhesion in tissue scaffolds [24] | Minimal immune activation; suitable for long-term implantation | FDA approved for various medical applications including wound care and tissue engineering [24] | Highly biodegradable through enzymatic action; degradation rate varies by crystallinity and functionalization [23] |

| Chitosan | Cell viability >90% even at high concentrations; supports epithelial cells, fibroblasts, osteoblasts, and chondrocytes [25] | Non-immunogenic; mucoadhesive properties reduce irritation | FDA GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) status; FDA approved as primary wound healing material (August 2023) [25] | Enzymatic hydrolysis by lysozymes; degradation rate depends on degree deacetylation and molecular weight [25] |

| Silk Fibroin | Promotes adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells; upregulates osteogenic markers [26] | Minimal inflammatory response; compatible with various tissues | Used in FDA-approved medical devices; extensive clinical history in sutures [27] | Controllable proteolytic degradation; rate tunable via cross-linking and processing [26] |

Quantitative Material Properties Comparison

Table 2: Comparative Physicochemical Properties for Bioelectronic Applications

| Property | Cellulose | Chitosan | Silk Fibroin | Test Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength (MPa) | Up to 1000 (crystal) | 20-50 (films) | 100-740 (fibers) | ASTM D638 |

| Young's Modulus (GPa) | 100-140 (crystal) | 2-7 | 5-17 | ASTM E111 |

| Degradation Time | Weeks to months | 2-12 weeks | 2 months to years | Enzymatic assay |

| Biocompatibility Score | Excellent | Excellent | Excellent | ISO 10993 |

| Surface Charge | Negative | Positive (pH-dependent) | Negative | Zeta potential |

| Water Absorption (%) | 60-1000 (hydrogels) | 100-600 | 100-300 | Gravimetric analysis |

Processing and Functionalization Methodologies

Material Processing and Scaffold Fabrication

Cellulose Processing: Regenerated cellulose fibers are produced through dissolution of natural cellulose sources (typically wood pulp or cotton linters) and reconstitution into fiber form. The viscose process—the most common method—involves steeping cellulose in sodium hydroxide, reaction with carbon disulfide to form cellulose xanthate, dissolution in dilute alkali to create viscose dope, and finally extrusion into an acidic coagulation bath to regenerate cellulose [24]. More recent environmentally friendly processes include the Lyocell process, which uses N-methylmorpholine N-oxide (NMMO) as a direct solvent in a closed-loop system that minimizes environmental impact [24].

Chitosan Nanoparticle Synthesis: Ionic gelation method represents the most prevalent technique for producing chitosan nanoparticles for drug delivery applications. The process involves dissolving chitosan in aqueous acidic solution (typically 1% acetic acid) to protonate amino groups, followed by dropwise addition of cross-linking agent (most commonly tripolyphosphate - TPP) under constant magnetic stirring at room temperature. The resulting nanoparticles are collected by ultracentrifugation (10,000-15,000 rpm for 30-60 minutes) and washed repeatedly with deionized water [25]. Critical parameters affecting nanoparticle characteristics include chitosan molecular weight and degree of deacetylation, chitosan-to-TPP ratio, pH, stirring speed, and temperature.

Silk Fibroin Processing: Silk fibroin is typically extracted from Bombyx mori cocoons through a multi-step purification process. Cocoons are boiled in 0.02M sodium carbonate solution for 30-60 minutes to remove sericin, the glue-like protein. The extracted fibroin fibers are then dissolved in 9.3M LiBr solution at 60°C for 4 hours, followed by dialysis against deionized water using cellulose tubular membranes (MWCO 3.5-14 kDa) for 48-72 hours to remove salt. The resulting aqueous silk fibroin solution can be processed into various material formats including films, hydrogels, sponges, and fibers through techniques like solvent casting, electrospinning, or freeze-drying [26].

Biofunctionalization Strategies

Surface modification of natural polymers enhances their functionality for specific bioelectronic applications. Chitosan's chemical versatility allows modification through primary amino groups at C2 and hydroxyl groups at C3 and C6 positions, enabling graft copolymerization, cross-linking, and polyelectrolyte complex formation to tailor stability, hydrophobicity, pharmacokinetics, solubility, durability, and biocompatibility [25]. Cellulose can be functionalized with antimicrobial agents (e.g., silver nanoparticles, iodine) for advanced wound care applications or with conductive polymers (e.g., PEDOT:PSS) for bioelectronic interfaces [24]. Silk fibroin's surface can be modified with cell-adhesive peptides (e.g., RGD sequences) to enhance cellular interaction or with inorganic nanoparticles (e.g., hydroxyapatite) to improve osteoconductivity for bone tissue engineering applications [26].

Applications in Bioelectronics and Therapeutic Platforms

Bioelectronic Interfaces and Implantable Devices

The mechanical mismatch between conventional electronic components and soft biological tissue represents a significant challenge in implantable bioelectronics, often leading to tissue damage, inflammation, and device failure [8]. Natural polymers address this limitation through their tunable mechanical properties and inherent biocompatibility. Recent research has demonstrated the development of fully elastomeric organic field-effect transistors made from blends of semiconducting nanofibers and biocompatible elastomers, exhibiting Young's modulus similar to human tissues and stable electrical performance under 50% strain [8]. These devices maintain functionality in logic circuits (including inverters, NOR gates, and NAND gates) under physiological conditions, with in vivo implantation studies in mice showing no major inflammatory response or tissue damage [8].

Cellulose-based substrates have been employed as flexible, biodegradable platforms for transient electronics, with tunable degradation rates matching specific clinical timeframes. Regenerated cellulose fibers demonstrate exceptional biocompatibility and moisture management capabilities, making them ideal for biointegrated sensing applications [24]. Their moderate cost, excellent biocompatibility, and ability to be sterilized via autoclaving or gamma radiation without losing structural integrity make them particularly suitable for clinical translation [24].

Drug Delivery Systems

Chitosan-based formulations exemplify the potential of natural polymers in advanced drug delivery applications. The unique mucoadhesive properties of chitosan, derived from its cationic nature, facilitate prolonged contact with mucosal surfaces, enhancing drug absorption and bioavailability [25]. Nanoparticles and microparticles fabricated from chitosan and its derivatives enable controlled release kinetics, with sustained drug release profiles lasting more than 72 hours [25]. The release mechanisms include diffusion from the carrier surface, diffusion through the matrix, and release due to erosion and/or degradation of the polymer, typically occurring in combination rather than isolation [25].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Natural Polymer Experimentation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Tripolyphosphate (TPP) | Ionic cross-linker for chitosan nanoparticles | Forms polyelectrolyte complexes with cationic chitosan; creates stable nanoparticles for drug encapsulation [25] |

| Lysozyme | Enzymatic degradation studies | Hydrolyzes glycosidic bonds in chitosan; used to simulate and study biodegradation profiles [25] |

| N-Methylmorpholine N-oxide (NMMO) | Direct cellulose solvent | Lyocell process for regenerated cellulose fibers; closed-loop environmentally friendly processing [24] |

| Lithium Bromide (LiBr) | Silk fibroin solvent | Dissolves degummed silk fibers to create aqueous silk solutions for biomaterial fabrication [26] |

| Glycerol | Plasticizing agent | Enhances flexibility and processability of natural polymer films; reduces brittleness [28] |

| Genipin | Natural cross-linker | Alternative to glutaraldehyde; crosslinks chitosan and other natural polymers with reduced cytotoxicity [25] |

Tissue Engineering Scaffolds

Silk fibroin has demonstrated exceptional utility in tissue engineering, particularly for bone regeneration where mechanical strength and osteoconductivity are critical requirements. The incorporation of SF into composite materials significantly enhances compressive strength, toughness, and structural stability through the formation of β-sheet crystal structures and intermolecular interactions [26]. SF promotes the adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells, upregulating the expression of key osteogenic markers such as alkaline phosphatase and osteocalcin through participation in signaling pathways [26]. When combined with ceramics or metal implants, SF-based composites demonstrate excellent osteogenic ability, providing a theoretical framework for creating composite bone repair materials with precise mechanical matching and efficient osteogenic induction functions [26].

Plant-based polymers, including cellulose and chitosan, offer sustainable alternatives for tissue engineering scaffolds, with inherent biocompatibility and adjustable physicochemical characteristics that support cell adhesion, proliferation, and extracellular matrix deposition [28]. These biomaterials provide distinct advantages over synthetic polymers, including reduced inflammatory responses and inherent bioactivity, though challenges remain in achieving sufficient mechanical strength for load-bearing applications without additional reinforcement strategies [28].

Experimental Protocols and Characterization

Biocompatibility Assessment Protocol

Comprehensive biocompatibility evaluation follows ISO 10993 standards and involves multiple assessment techniques:

Cell Viability Assay (MTT Assay): Seed cells (e.g., human dermal fibroblasts) in 96-well plates at density of 1×10ⴠcells/well and culture for 24 hours. Prepare polymer extracts by incubating sterile material samples in complete cell culture medium at 37°C for 24 hours at surface area-to-volume ratio of 3 cm²/mL. Replace cell culture medium with material extracts and incubate for 24-72 hours. Add MTT solution (0.5 mg/mL) and incubate for 4 hours. Dissolve formed formazan crystals with DMSO and measure absorbance at 570 nm with reference at 630 nm [25].

Hemocompatibility Testing: Collect fresh human whole blood with anticoagulant. Incubate polymer samples with diluted blood (1:10 in PBS) at 37°C for 1 hour with gentle mixing. Centrifuge and measure hemoglobin release at 540 nm. Calculate hemolysis percentage relative to positive (water) and negative (PBS) controls. Values below 5% indicate acceptable blood compatibility [29].