Advancing Long-Term Neural Signal Fidelity: Materials, Methods, and Mitigation Strategies for Next-Generation Brain Interfaces

This article synthesizes the latest advancements and persistent challenges in achieving high-fidelity long-term neural recordings, a cornerstone for progress in neuroscience research, drug development, and clinical brain-computer interfaces.

Advancing Long-Term Neural Signal Fidelity: Materials, Methods, and Mitigation Strategies for Next-Generation Brain Interfaces

Abstract

This article synthesizes the latest advancements and persistent challenges in achieving high-fidelity long-term neural recordings, a cornerstone for progress in neuroscience research, drug development, and clinical brain-computer interfaces. We explore the fundamental obstacles of signal degradation, from foreign body reactions to technological bottlenecks in data transmission. The content details innovative methodological breakthroughs in flexible electrodes, bioadaptive coatings, and on-implant processing. Furthermore, it provides a critical analysis of troubleshooting strategies for issues like crosstalk and mechanical mismatch, and offers a comparative validation of emerging technologies, equipping researchers and professionals with a comprehensive overview of the field's current state and future trajectory.

The Core Hurdles: Understanding the Biological and Technical Barriers to Stable Neural Recordings

The long-term stability of intracortical neural interfaces is fundamentally constrained by the brain's biological response to implanted devices. This foreign body reaction (FBR) is a complex, multi-stage process that begins with acute injury and can culminate in the formation of an insulating glial scar at the tissue-electrode interface [1] [2]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this cascade is critical, as the ensuing chronic inflammation and scarring are major contributors to signal degradation over time, ultimately limiting the efficacy of chronic neural recording and stimulation technologies [3] [2]. This guide objectively compares the key biological stages and their impact on signal fidelity, supported by experimental data and methodologies central to the field. The overarching thesis is that signal longevity depends not merely on the initial electrode performance but on mitigating the dynamic and persistent tissue response.

The Biological Cascade: From Implantation to Chronic Scarring

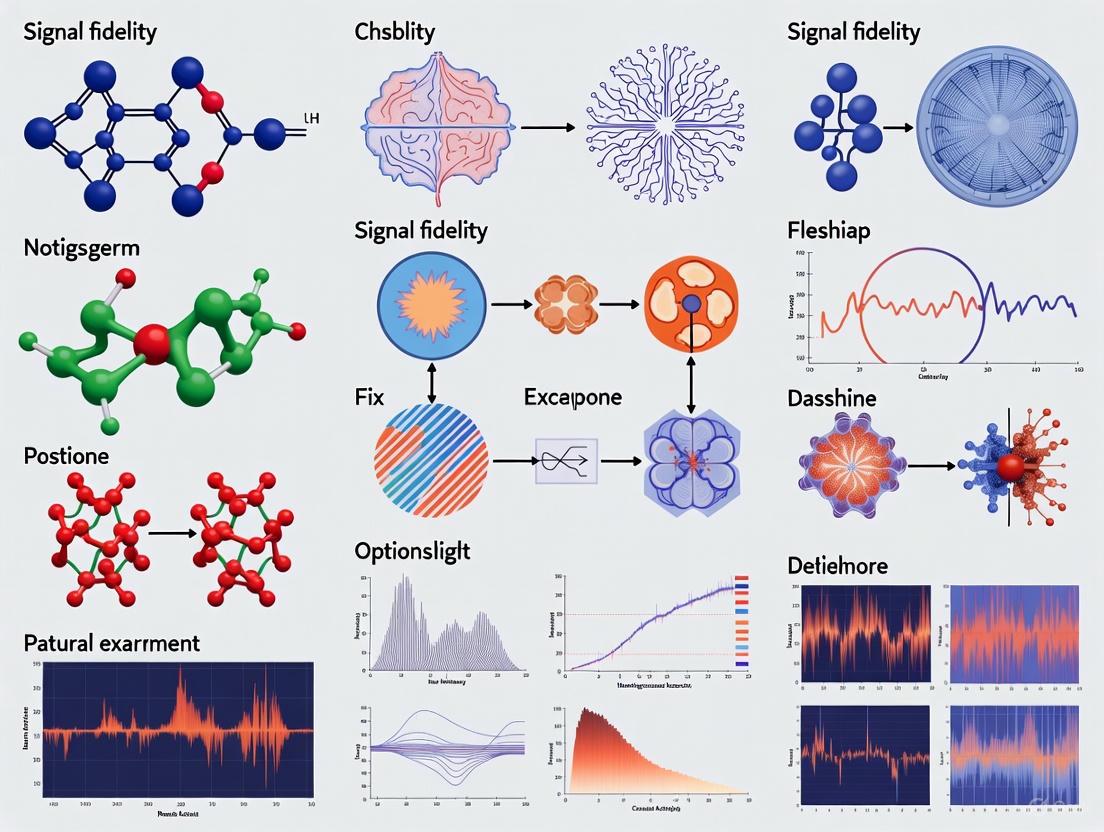

The tissue response to an implanted neural probe is a timed sequence of events, progressing from immediate injury to a chronic foreign body reaction. The following diagram illustrates the key stages and their interrelationships.

Diagram 1: The sequential progression of the foreign body reaction following neural probe implantation, culminating in glial scarring and signal degradation.

Stage 1: Acute Injury and Inflammation

The initial implantation trauma severs blood vessels and neural processes, causing bleeding and the release of blood plasma contents into the brain tissue [2]. This triggers an acute inflammatory response characterized by the recruitment of neutrophils and the activation of microglia, the brain's resident immune cells [1] [2]. A critical early event is the instantaneous adsorption of blood proteins (e.g., fibrinogen, albumin, complement) onto the probe surface, forming a "provisional matrix" that dictates subsequent cellular interactions [1].

Stage 2: Chronic Inflammation and Foreign Body Reaction

Within days, the acute response transitions to a chronic inflammatory phase dominated by monocytes and lymphocytes [1]. Blood-derived macrophages and activated microglia congregate at the implant interface [2]. A hallmark of the chronic FBR is the fusion of macrophages to form foreign body giant cells (FBGCs), which persist at the interface for the device's lifetime and participate in the chronic inflammatory response [1].

Stage 3: Gliosis and Glial Scar Formation

The persistent presence of the implant and the inflammatory milieu lead to reactive astrogliosis, where astrocytes undergo hypertrophy, proliferate, and upregulate expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) [2]. Along with activated microglia, these reactive astrocytes form a dense, insulating barrier around the implant known as the glial scar [3] [4]. While this scar tissue can functionally insulate the electrode, its effect on signal quality is complex and influenced by multiple factors, as detailed in the following sections.

Comparative Analysis of Factors Influencing the FBR and Signal Quality

The extent of the FBR and its impact on recording stability are modulated by several probe-related factors. The table below synthesizes experimental findings on how key properties influence tissue response and signal outcomes.

Table 1: Comparison of Neural Probe Properties and Their Impact on the Foreign Body Reaction

| Probe Property | Experimental Findings & Impact on FBR | Effect on Recording Signal |

|---|---|---|

| Probe Density [4] | High-density probes (e.g., platinum, 21.45 g/cm³) cause significantly larger astrocytic scars (GFAP intensity) than low-density probes (~1.35 g/cm³), despite similar size/shape/surface. Inertial forces from density mismatch drive scarring. | Not directly measured, but a larger astrocytic scar is hypothesized to increase functional insulation of the electrode. |

| Probe Size/Cross-section [3] | Smaller probes displace less tissue, disrupt fewer capillaries, and reduce biomolecule adsorption. This minimizes the initial injury and subsequent perfusion deficits, supporting neuronal health near the interface. | Directly linked to improved long-term stability. Smaller, slender probes allow for nearly "seamless" integration and sustained high-quality recordings [3]. |

| Probe Flexibility [3] | Flexible probes mitigate micro-motions caused by brain pulsations, reducing secondary trauma and chronic irritation. Stiff, tethered probes translate skull-brain movements into tissue damage. | Reduces chronic inflammation and gliosis, promoting a stable interface and consistent signal quality over time. |

| Biofouling & Interface Resistivity [5] | A thin, non-cellular interface layer of adsorbed proteins (biofouling) on the electrode tip is a primary driver of increased impedance. Glial scarring alone may not fully explain electrical changes. | A biofouling-induced increase in interface resistivity raises impedance but may not significantly affect recorded spike amplitude unless neurons are displaced [5]. |

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing the FBR

Research in this field relies on a combination of in vivo electrophysiology, histology, and computational modeling to dissect the components of the FBR.

In Vivo Electrophysiology and Impedance Tracking

Objective: To chronically monitor the electrical performance of implanted electrodes and correlate changes with the biological response.

Methodology:

- Implantation: Microelectrode arrays (e.g., Utah Array, Michigan probes) are surgically implanted into the target brain region of animal models (e.g., non-human primates, rats) [5].

- Recording: Neural signals (single-unit and multi-unit activity) and electrode impedance are tracked regularly over weeks to months. Key metrics include signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), spike amplitude, and impedance at 1 kHz [5].

- Data Analysis: Trends are analyzed, such as an initial increase in impedance and amplitude followed by stabilization or decline, which are then correlated with histological endpoints.

Histopathological Analysis and Immunohistochemistry

Objective: To quantitatively assess the cellular components of the FBR post-mortem.

Methodology:

- Perfusion and Sectioning: After a predetermined period, animals are perfused, and brain tissue is sectioned for analysis. In some protocols, probes are explanted to examine cells adhering to the implant surface [4].

- Staining: Tissue sections are stained with specific antibodies to identify key cell types:

- Anti-GFAP: Labels reactive astrocytes to quantify astrogliosis and glial scar thickness [2] [4].

- Anti-CD68 (ED1): Labels activated microglia and macrophages to assess the innate immune response [2] [4].

- Anti-NeuN: Labels neuronal nuclei to quantify neuronal density and loss around the implant site [4].

- Quantification: Staining intensity and cell density are measured at defined distances from the implant track (e.g., 0-50 μm, 50-100 μm) to create a quantitative profile of the FBR [4].

Data-Driven Computational Modeling

Objective: To isolate the individual contributions of glial scarring and biofouling to electrical changes.

Methodology:

- Model Construction: A finite-element model of the electrode in tissue is coupled with a multi-compartmental neuron model [5].

- Parameter Variation: The model incorporates variables such as encapsulation layer thickness (simulating glial scar), encapsulation resistivity, and interface resistivity (simulating biofouling) [5].

- Validation: Model outputs (impedance, signal amplitude) are reconciled with longitudinal in vivo data and histology to determine which biological factors best explain the observed electrical changes [5]. This approach demonstrated that a thin, high-resistance interface layer, rather than the glial scar itself, was the primary cause of rising impedance.

The workflow for integrating these methodologies is summarized below.

Diagram 2: The integrated experimental workflow for investigating the foreign body reaction, combining in vivo data, histology, and computational modeling.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for FBR Studies

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Microelectrode Arrays (e.g., Utah Array, Michigan Probe) | The implanted device for chronic neural recording and stimulation; the subject of the FBR [2] [5]. |

| Anti-GFAP Antibody | Primary antibody for immunohistochemical labeling of reactive astrocytes, enabling quantification of astrogliosis [2] [4]. |

| Anti-CD68 (ED1) Antibody | Primary antibody for immunohistochemical labeling of activated microglia and infiltrating macrophages [2] [4]. |

| Anti-NeuN Antibody | Primary antibody for labeling neuronal nuclei to assess neuronal density and viability near the implant [4]. |

| Parylene C | A common, biocompatible polymer used as an insulating coating for neural probes to isolate the effect of underlying material properties [4]. |

| Finite-Element Modeling Software (e.g., COMSOL) | Platform for building computational models to simulate the electrical properties of the electrode-tissue interface and deconstruct contributing factors [5]. |

| D-Biopterin | 2-amino-6-(1,2-dihydroxypropyl)-3H-pteridin-4-one (Biopterin) |

| Indolelactic acid | Indole-3-lactic Acid|High-Purity ILA Reagent |

The journey from acute inflammation to chronic glial scarring represents the central challenge to achieving stable, long-term neural recordings. The foreign body reaction is not a single entity but a multifaceted process driven by initial injury, mechanical forces (from density and stiffness mismatches), and persistent immune activation. A critical insight from recent research is that the glial scar itself may not be the primary electrical barrier to signal quality; instead, a thin biofouling layer at the electrode interface may be a more significant factor in impedance increases [5]. This paradigm shift suggests that future engineering strategies must move beyond a singular focus on eliminating gliosis and instead pursue integrated solutions that address probe biomechanics (miniaturization, flexibility, density), surface chemistry (to minimize biofouling), and the underlying inflammatory cascade. For the field to advance, the continued development and application of the sophisticated experimental protocols and reagents detailed herein will be essential for disentangling this complex biological puzzle. :::

The evolution of brain-implantable microsystems has entered a critical phase where engineering advancements in microelectrode array fabrication have dramatically outpaced capabilities for handling the resulting neural data. High-density microelectrode arrays (HD-MEAs) with thousands of recording channels represent the frontier of neural interfacing technology, enabling unprecedented access to brain activity with exceptional spatial and temporal resolution [6] [7]. However, this remarkable recording capability has created a fundamental engineering constraint: the wireless transmission bottleneck. As channel counts escalate to 10,000+ electrodes, the massive data volumes generated threaten to overwhelm both the power budgets and transmission bandwidth of implantable systems [6] [8]. This comparative analysis examines the core technical challenges and emerging solutions for maintaining signal fidelity while overcoming data transmission constraints in next-generation neural interfaces.

The central dilemma is straightforward yet formidable. While microfabrication technologies now enable creating microelectrode arrays with extreme channel densities (>3000 electrodes per mm²), simultaneously streaming raw data from all these channels would require wireless data rates that are physiologically and technically implausible for implantable devices [6]. For instance, a 1,024-channel system sampling at 30 kHz with 10-bit resolution would generate a continuous data stream of approximately 307 Mbps before accounting for overhead—far exceeding practical limits for implanted transmitters operating under strict power constraints [8]. This review systematically compares the predominant strategies being developed to resolve this critical bottleneck while preserving the neural information essential for both basic neuroscience and clinical applications.

Technical Challenges in High-Density Neural Data Transmission

The Scaling Problem: Data Volume Versus Transmission Capacity

The fundamental challenge stems from an exponential growth in data generation that linearly outpaces improvements in transmission efficiency. Contemporary HD-MEAs now accommodate up to 236,880 electrodes with simultaneous readout from 33,840 channels at 70 kHz sampling rates [7]. The raw data output from such systems would approach several gigabits per second—far beyond the capabilities of any existing implantable wireless technology under power constraints suitable for safe human implantation [6].

Table 1: Microelectrode Array Scaling Trends and Data Generation

| Parameter | Traditional Arrays | Current HD-MEAs | Next-Generation HD-MEAs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Channel Count | 10-100 electrodes | 1,000-10,000 electrodes | 10,000-100,000 electrodes |

| Electrode Density | 10-100/mm² | 100-1,000/mm² | >1,000/mm² |

| Raw Data Rate | 1-10 Mbps | 100 Mbps - 1 Gbps | >1 Gbps |

| Spatial Resolution | Network-level activity | Multi-unit activity | Single-unit, subcellular |

| Primary Limitation | Signal quality | Data transmission | Power efficiency & heat dissipation |

The wireless telemetry technologies currently available for brain implants present severe limitations for high-density data transmission. Radio frequency (RF) links, commonly used in medical implants, typically offer bit rates below 100 Mbps with communication ranges of a few centimeters [6]. While ultra-wideband (UWB) and optical links can provide higher data rates, they face challenges with tissue penetration and power efficiency. As illustrated in Figure 5 of the search results, even the most advanced wireless technologies struggle to support the multi-gigabit per second requirements of uncompressed full-bandwidth data from next-generation HD-MEAs [6].

Power and Thermal Constraints

Beyond pure data rate limitations, implantable systems operate under exceptionally strict power budgets—typically sub-milliwatt per channel—to prevent tissue heating and damage [6] [8]. The power consumption of wireless transmitters increases super-linearly with data rate, making raw data transmission prohibitively expensive from a power perspective. Additionally, heat dissipation becomes a critical safety concern when processing and transmitting massive data volumes within confined implant packages [7]. These constraints fundamentally necessitate a paradigm shift from "transmit everything" to "process intelligently and transmit selectively."

Comparative Analysis of Data Reduction Strategies

On-Implant Signal Processing Techniques

The most promising approach to overcoming the transmission bottleneck involves performing sophisticated signal processing directly on the implant to reduce data volume before transmission. These techniques can be broadly categorized into temporal compression, spatial compression, and feature extraction methods, each with distinct trade-offs between compression efficiency, computational complexity, and signal fidelity preservation [6].

Table 2: Comparison of On-Implant Data Reduction Techniques

| Technique | Compression Principle | Compression Ratio | Hardware Efficiency | Information Preservation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spike Detection & Extraction | Discards inter-spike data | 10-100x (dependent on firing rate) | Very High | Only preserves action potentials |

| Salient Sample Compression | Transmits key spike features | 2000x+ (at 8 spikes/s) | High | Reconstructs spike waveforms |

| Transform-Based Methods | Projects signals to compact domain | 10-50x | Moderate | Near-lossless reconstruction |

| Spatial Compression | Exploits channel correlation | 5-20x | Moderate | Preserves spatial relationships |

| Compressive Sensing | Sub-Nyquist sampling | 4-16x | Low-Moderate | Theoretical perfect reconstruction |

Spike detection and extraction represents the most established approach, where only the action potential waveforms are preserved while discarding background neural data between spikes [6] [8]. This method achieves compression ratios of 10-100x, depending on neuronal firing rates, with minimal computational overhead. However, it irrevocably discards local field potential (LFP) information and requires careful spike detection thresholds to avoid losing valuable neural events [6].

Advanced Compression Methodologies

Salient Sample Extraction and Curve Fitting

A particularly innovative approach recently demonstrated achieves remarkable compression ratios exceeding 2000x through a method called salient sample extraction and curve fitting [8]. This technique identifies critical points in spike waveforms (start/end points and extremum points) and transmits only these features rather than complete waveforms. On the external side, predefined smooth curves are fit to these points to reconstruct spike shapes.

The experimental protocol for this method involves:

- Spike detection using amplitude thresholding or more sophisticated algorithms

- Salient point identification through analysis of triplets of consecutive samples to detect slope sign changes

- Feature encoding of salient point timing and amplitudes

- Wireless transmission of compressed feature set

- Waveform reconstruction on external equipment using polynomial fitting functions

This approach achieves unprecedented compression while maintaining signal fidelity, with the added benefit of inherent noise reduction through the curve-fitting process [8]. Hardware implementation in 130-nm CMOS technology consumes only 0.164 µW per channel at 1V supply—well within the strict power constraints of implantable devices [8].

Transform-Based and Spatial Compression

Transform-based methods including discrete wavelet transform (DWT), discrete cosine transform (DCT), and Walsh-Hadamard transform (WHT) project neural signals into alternative domains where they can be represented more compactly [6] [8]. These techniques typically achieve moderate compression ratios (10-50x) with better preservation of original signal morphology compared to spike-only approaches.

Spatial compression techniques exploit the inherent correlation between adjacent recording channels to reduce redundancy in multi-channel neural data [8]. Methods such as the whitening transform and MBED technique have demonstrated effectiveness, particularly as electrode densities increase and the spatial correlation between channels becomes more pronounced [8].

Signal Fidelity Considerations in Long-Term Neural Recording

The Fidelity-Compression Tradeoff

A central tension in neural data compression lies in balancing compression efficiency against signal fidelity preservation. Different neural applications require different aspects of signal fidelity—for motor decoding applications, precise spike timing may be paramount, while for neurological disorder monitoring, specific LFP frequency bands might carry critical information [6] [9].

The non-linear modeling of complete neural recording systems has revealed that different components contribute unequally to overall signal degradation [9]. Specifically, analog-to-digital converter (ADC) non-linearity has a greater impact on system performance than front-end amplifier non-linearity, providing crucial guidance for optimizing system design when balancing performance against power and area constraints [9].

Long-Term Stability Challenges

Maintaining signal fidelity over extended implantation periods presents additional challenges related to foreign body response, biofouling, and electrode impedance changes [10]. Recent advances in bioadaptive interfaces have demonstrated promising approaches for sustained high-quality recording. The TAB (targeting-specific interaction and blocking nonspecific adhesion) coating strategy combines brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) conjugation with a lubricant-infused surface to promote positive neural interactions while minimizing inflammatory response [10].

Experimental results with TAB-coated fibers demonstrated high-quality single-unit neural signals maintained for over 12 months post-implantation, representing a significant advancement for long-term neural interfaces [10]. This sustained performance is crucial for clinical applications where stable decoding performance over years is required.

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Protocol 1: Evaluating Compression Efficacy

To objectively compare compression techniques, researchers should implement the following standardized protocol:

- Data Acquisition: Record neural data using HD-MEAs from appropriate models (in vitro cultures, animal models, or human intraoperative recordings)

- Ground Truth Establishment: Manually curate a subset of data with expert-labeled spikes and LFPs

- Algorithm Application: Apply each compression technique to the same dataset

- Performance Metrics Calculation:

- Compression Ratio: Original size / compressed size

- Spike Detection Accuracy: Precision, recall, F1-score compared to ground truth

- Waveform Reconstruction Error: Mean squared error between original and reconstructed spikes

- Decoding Performance: Comparison of information transfer rates in brain-computer interface tasks

- Hardware Efficiency Assessment: Measure power consumption, silicon area, and processing latency for implant implementation

Protocol 2: Long-Term Signal Stability Assessment

For evaluating sustained performance in chronic implants:

- Surgical Implantation: Precisely place HD-MEAs using minimally invasive techniques [11]

- Longitudinal Monitoring: Regularly acquire neural data over weeks to months

- Signal Quality Metrics: Track signal-to-noise ratio, unit yield, and amplitude stability over time

- Histological Correlation: Upon endpoint, examine tissue response and electrode encapsulation

The cranial micro-slit technique described in recent literature enables minimally invasive implantation of high-density arrays while minimizing tissue damage [11]. This procedure uses 500-900μm wide incisions for subdural insertion of thin-film arrays without requiring full craniotomy, significantly improving recovery and long-term viability [11].

Research Reagent Solutions for Neural Interface Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Experimental Tools

| Reagent/Technology | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| CMOS HD-MEA Chips | Neural signal acquisition | High electrode density, integrated electronics, scalable manufacturing [7] |

| Flexible Thin-Film Arrays | Cortical surface recording | Conformable to brain surface, minimal mechanical mismatch [11] |

| TAB Coating | Surface modification for long-term stability | BDNF conjugation + lubricant infusion reduces fouling [10] |

| Salient Sample Compression ASICs | On-implant data reduction | Custom CMOS implementation, ultra-low power operation [8] |

| Bioadaptive Polymer Substrates | Neural probe fabrication | Mechanical compliance matching neural tissue [10] |

| Wireless Telemetry Systems | Data transmission from implant | UWB, RF, or infrared based on application requirements [6] |

Emerging Directions and Future Prospects

The field of neural interface data handling is rapidly evolving toward more intelligent, adaptive approaches. Machine learning-based compression techniques show promise for dynamically optimizing compression strategies based on neural content and application requirements [12]. Additionally, hierarchical processing approaches that combine multiple compression techniques adaptively may further push the boundaries of what is achievable within strict implant power budgets.

Future systems will likely incorporate closed-loop operation where neural recording, processing, and stimulation are tightly integrated [6] [7]. In such systems, efficient data handling becomes even more critical as computational resources must be shared between decoding algorithms and stimulus optimization routines.

The continuing progression toward higher channel counts necessitates a fundamental rethinking of neural data paradigms. Rather than attempting to transmit increasingly massive raw data streams, the field is shifting toward on-implant feature extraction where only behaviorally or clinically relevant information is communicated externally [6] [8]. This approach aligns with both technical constraints and the fundamental goal of neural interfaces—to extract meaningful information about brain function and dysfunction.

The data transmission bottleneck in high-density neural interfaces represents both a formidable challenge and a catalyst for innovation in neural engineering. Through comparative analysis of current approaches, it is evident that no single solution optimally addresses all requirements for compression efficiency, computational complexity, and signal fidelity preservation. The most promising path forward involves context-appropriate selection and combination of techniques based on specific application requirements—whether for basic neuroscience research, clinical brain-computer interfaces, or therapeutic neurostimulation.

As microfabrication technologies continue to push the boundaries of electrode density, parallel advancements in on-implant processing algorithms and hardware implementation will be essential to realize the full potential of next-generation neural interfaces. The ongoing development of sophisticated yet power-efficient compression strategies, coupled with bioadaptive materials that ensure long-term signal stability, promises to overcome current limitations and enable transformative applications in understanding and treating neurological disorders.

The clinical success of implantable neural interfaces, from deep brain stimulation (DBS) for Parkinson's disease to brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) for paralysis, is fundamentally constrained by a single physical property: mechanical mismatch [13]. This mismatch arises from the vast difference in stiffness between traditional electrode materials and the soft neural tissues they penetrate. While the brain exhibits a Young's modulus of approximately 1-10 kPa, conventional electrode materials such as silicon (~130-185 GPa) and platinum (~102 GPa) are orders of magnitude stiffer [14] [15]. This mechanical disparity creates a significant interface problem, initiating a cascade of biological responses that ultimately compromise recording stability and stimulation efficacy.

This article examines how this mechanical mismatch induces chronic inflammation through micro-motion damage, directly impacting the long-term signal fidelity crucial for both basic neuroscience research and clinical applications. We compare the performance of traditional rigid electrodes against emerging mechanically-compliant alternatives, providing experimental data and methodologies that inform material selection and device design for researchers and drug development professionals.

The Fundamental Mechanisms of Damage

Biomechanical Principles and Strain Modeling

The primary mechanical conflict at the neural interface stems from the bending stiffness (K) of the implant, which scales linearly with Young's modulus (E) and to the third power with thickness (h) for a rectangular shank, as defined by the equation ( K = E \cdot \frac{bh^3}{12} ) (where b is width) [16] [17]. This relationship means that reducing thickness has a dramatically greater impact on flexibility than changing material composition.

Finite Element Modeling (FEM) reveals how this stiffness discrepancy translates to tissue damage. When a 20 µm displacement is applied to simulate brain micromotion, rigid implants induce concentrated strain along their surfaces and particularly at the tips [14] [18]. This strain is further focused on small protrusions such as electrical traces and recording sites. One study demonstrated that the mechanical mismatch between iridium and silicon within a single device creates additional focal points of strain, leading to material failure over time [18].

Table 1: Mechanical Properties of Neural Tissues and Interface Materials

| Material/Tissue | Young's Modulus | Key Characteristics | Impact on Interface |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brain Tissue | 1-10 kPa | Viscoelastic, compliant | Reference baseline for compatibility |

| Silicon (Michigan Probe) | 130-185 GPa | Rigid, brittle | Significant mechanical mismatch |

| Platinum | ~102 GPa | Ductile, conductive | High stiffness mismatch |

| Polyimide | ~2.5 GPa | Flexible polymer | Reduced but still present mismatch |

| Mechanically-Adaptive Nanocomposite | 5.2 GPa → 12 MPa | Softens upon implantation | Drastically reduced chronic mismatch |

The Biological Cascade: From Micro-Motion to Chronic Inflammation

The initial implantation itself causes acute injury, but the persistent inflammatory response is primarily driven by the ongoing mechanical mismatch. The biological response evolves through several key phases [17]:

Acute Phase (Days): Insertion disrupts the blood-brain barrier, causing bleeding and releasing inflammatory factors that attract immune cells to clear debris.

Chronic Phase (Weeks to Months): Continuous micromotion between the rigid implant and surrounding tissue causes recurring damage, sustaining the inflammatory response. Microglia activate and release cytokines and reactive oxygen species, while astrocytes proliferate and migrate to the injury site.

Encapsulation Phase (Months+): Astrocytes secrete extracellular matrix components, forming a dense physical barrier of glial scar tissue around the electrode. This scar electrically insulates the electrode, increasing impedance and signal attenuation.

The following diagram illustrates this cascade, showing how mechanical mismatch initiates a biological response that ultimately degrades signal quality.

Performance Comparison: Rigid vs. Compliant Electrodes

Histological and Functional Outcomes

Direct comparisons between rigid and compliant implants reveal striking differences in long-term tissue integration and functional stability. A pivotal study investigating mechanically-adaptive nanocomposites—initially rigid for implantation but softening to ~12 MPa under physiological conditions—demonstrated significantly improved outcomes compared to stiff controls [14].

Table 2: Comparative Tissue Response: Rigid vs. Compliant Implants

| Parameter | Rigid Implants (e.g., Silicon, PVAc-coated Silicon) | Compliant Implants (e.g., Mechanically-Adaptive Nanocomposites) | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Response (3 days) | Significant BBB disruption, cell death at interface | Statistically similar tissue response | No significant difference in early healing phase [14] |

| Chronic Inflammation (2-16 wks) | Sustained elevated microglial and astrocytic activation | Significantly reduced glial activation at all chronic time points | Immunohistochemistry showing reduced GFAP+ and Iba1+ cells [14] |

| Blood-Brain Barrier Stability | Persistent leakage around implant | More stable BBB over chronic periods | Immunohistochemistry for albumin and other serum proteins [14] |

| Neuronal Density | Late-onset neurodegeneration with neuronal loss | Better preserved neuronal populations near interface | NeuN staining showing higher neuronal density at 16 weeks [14] |

| Recording Longevity | Signal degradation over weeks to months | Improved signal stability demonstrated in animal models | Lower impedance drift and more stable single-unit recordings over months [16] [19] |

Quantitative Data on Strain and Scarring

Finite element models provide quantitative insight into why compliant materials produce superior histological outcomes. One analysis revealed that the maximum strain in brain tissue surrounding a traditional silicon electrode was significantly higher than around ultraflexible electrodes with subcellular dimensions [16]. This reduced strain directly correlates with thinner glial scar formation—typically 50-100 µm around compliant implants compared to 200-500 µm around rigid interfaces [16] [13].

The following experimental workflow outlines the key methodologies used to generate this comparative data, from material fabrication through to histological analysis.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Interface Stability

Chronic In Vivo Evaluation

To generate the comparative data presented in this review, researchers employ standardized protocols for long-term assessment of neural interfaces [14] [18]:

Animal Surgery and Implantation:

- Animals (typically rats or mice) receive bilateral implants with different materials in contralateral hemispheres to control for biological variability.

- Implants are inserted approximately 2 mm deep into cortical tissue (e.g., primary visual or motor cortex) by hand or with controlled insertion systems.

- Devices are tethered to the skull using Kwik-sil and dental acrylic to minimize external motion transmission.

- Animals are euthanized at multiple time points (e.g., 3 days, 2, 8, and 16 weeks) to capture both acute and chronic responses.

Electrophysiological Assessment:

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): Regularly measured to track changes at the electrode-tissue interface. Stable, low impedance indicates healthy integration.

- Single-Unit Recording: Quality and quantity of detectable neuronal action potentials are tracked over time. Signal-to-noise ratio and number of discriminable units serve as key metrics.

- Local Field Potential (LFP) Recording: Monitors broader network activity and stability.

Post-Mortem Histological Analysis

Tissue Processing and Staining:

- Transcardial perfusion with paraformaldehyde followed by brain extraction and cryosectioning.

- Immunohistochemistry for specific cell types:

- NeuN: Labels neuronal nuclei to quantify neuronal density and distribution near interface.

- GFAP: Identifies reactive astrocytes involved in glial scar formation.

- Iba1: Marks activated microglia mediating inflammatory response.

- Laminin or Albumin: Assess blood-brain barrier integrity.

Quantitative Morphometrics:

- Cell counting within standardized distances from the implant track (e.g., 0-50 µm, 50-100 µm, 100-200 µm).

- Measurement of glial scar thickness based on GFAP intensity profiles.

- 3D reconstruction of implant tracks to assess tissue deformation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Neural Interface Research

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanically-Adaptive Nanocomposites (PVAc/tCNC) | Soften upon implantation to match brain mechanics | Reducing chronic inflammation in cortical implants [14] |

| Ultraflexible Polymers (Polyimide, Parylene-C, SU-8) | Substrate materials with reduced bending stiffness | Fabrication of flexible electrode arrays with lower Young's modulus [16] [19] |

| Conductive Polymers (PEDOT:PSS) | Coatings to reduce electrode impedance and improve signal transduction | Enhancing signal-to-noise ratio in recording electrodes [19] |

| Nature-Derived Materials (Silk fibroin, Chitosan) | Biocompatible coatings and dissolvable sacrificial layers | Improving tissue integration and reducing FBR [20] |

| Dexamethasone-loaded Coatings | Controlled anti-inflammatory drug release | Actively suppressing immune response at implantation site [20] |

| Tungsten Wire Guidance Systems | Temporary stiffeners for implanting flexible electrodes | Enabling precise insertion of ultraflexible probes [17] |

| (E)-Cinnamamide | Cinnamamide|621-79-4|Research Chemical | |

| Decacyclene | Decacyclene, CAS:191-48-0, MF:C36H18, MW:450.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The evidence overwhelmingly demonstrates that mechanical mismatch is a primary determinant of long-term neural interface failure. The micro-motion between rigid implants and soft neural tissue sustains a chronic inflammatory response that culminates in glial scar formation, neuronal loss, and signal degradation. Compliant materials—particularly those that match the mechanical properties of brain tissue—consistently demonstrate reduced inflammatory markers, preserved neuronal density, and more stable electrical performance over chronic periods.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings highlight that material selection is not merely an engineering concern but a fundamental biological consideration. The move toward mechanically-compliant interfaces represents a paradigm shift in neural interface design, one that prioritizes seamless integration over brute-force functionality. As the field advances, the combination of compliant materials, sophisticated implantation strategies, and bioactive coatings offers the most promising path toward neural interfaces that remain stable and functional for decades—a crucial requirement for both basic neuroscience and clinical applications.

Biofouling and its Impact on Electrode-Tissue Interface Impedance and Signal Quality

The long-term stability of implantable neural electrodes represents a fundamental barrier in brain-computer interface (BCI) technology and chronic neural recording research. Biofouling—the unwanted adsorption of biological material and subsequent inflammatory response to implanted neural electrodes—directly compromises signal fidelity by increasing electrode-tissue interface impedance and degrading recording quality [15]. This biological process initiates immediately upon electrode implantation and evolves through characteristic phases, ultimately resulting in the formation of an insulating scar tissue layer that physically separates recording sites from their target neurons [17] [15]. The foreign body response triggered by electrode implantation activates microglia and astrocytes, which proliferate and migrate to the injury site, secreting inflammatory cytokines and extracellular matrix components that form a dense physical barrier around the implant [17]. This review systematically analyzes the biofouling cascade at neural interfaces, evaluates its quantifiable impacts on electrical properties and signal quality, compares testing methodologies for antifouling strategies, and identifies promising research directions for maintaining signal fidelity in chronic neural recordings.

The Biofouling Cascade: From Acute Implantation to Chronic Encapsulation

The biofouling process at neural electrode interfaces follows a well-defined temporal sequence involving distinct but overlapping biological events. Understanding this cascade is essential for developing targeted interventions to mitigate its effects on signal recording quality.

Phases of the Foreign Body Response

Acute Inflammatory Phase: The implantation procedure itself causes mechanical trauma, damaging blood vessels and neural tissue. This initial injury triggers the release of inflammatory factors that recruit immune cells to phagocytose cellular debris [17]. The geometric and mechanical mismatch between the electrode and brain tissue exacerbates this acute tissue damage, particularly with traditional rigid electrodes that have significantly higher Young's modulus (~102 GPa for silicon) compared to neural tissue (1-10 kPa) [15].

Chronic Inflammatory Phase: Following the acute response, persistent mechanical mismatch between the implant and surrounding tissue leads to continuous micromotion-induced friction, causing ongoing tissue damage [17]. This sustained injury activates microglia, which release inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species [17] [15]. Concurrently, astrocytes proliferate and migrate toward the implant site, secreting extracellular matrix (ECM) components [17].

Fibrous Encapsulation Phase: The accumulated ECM components and aligned glial cells eventually form a compact, insulating cellular layer around the electrode—a glial scar [17] [15]. This scar tissue creates a physical barrier that increases the distance between neurons and recording sites, leading to progressive signal attenuation and impedance elevation [17].

The following diagram illustrates this sequential biofouling process and its direct consequences for signal recording quality:

Key Cellular and Molecular Mediators

The cellular response to implanted electrodes involves coordinated activity of multiple cell types. Microglia, the resident immune cells of the central nervous system, become activated within hours of implantation and attempt to phagocytose the foreign material [17] [15]. When unable to remove the electrode, they transition to a chronic activated state, releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, which perpetuate the inflammatory environment [15]. Astrocytes undergo reactive gliosis, characterized by hypertrophy, proliferation, and increased expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) [17]. These reactive astrocytes migrate toward the implant and secrete chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans and other ECM components that contribute to the glial scar [17]. The resulting scar tissue typically consists of 50-100 μm thick layers of activated microglia and astrocytes surrounding the electrode, creating a significant physical barrier that can displace neurons by 100-500 μm from the recording sites [15].

Quantifiable Impacts on Interface Impedance and Signal Quality

Biofouling-induced tissue changes produce measurable alterations in the electrochemical properties of the electrode-tissue interface and directly impact the quality of recorded neural signals.

Impedance Changes and Signal Attenuation

The formation of glial scar tissue around neural electrodes significantly increases the electrical impedance at the electrode-tissue interface, particularly at frequency ranges relevant for neural recording [15]. This impedance elevation occurs because the scar tissue acts as a resistive barrier between the electrode and electrically active neurons. Studies have reported impedance increases of 200-500% over implantation periods of 4-12 weeks in various animal models, with the most dramatic rises occurring during the initial inflammatory phase [15]. The corresponding increase in physical distance between neurons and recording sites results in signal amplitude attenuation of 70-90% for single-unit recordings, often rendering previously detectable neurons unrecoverable from the noise floor [15]. The table below summarizes key quantitative relationships between biofouling progression and signal quality parameters:

Table 1: Biofouling Impact on Neural Signal Quality Parameters

| Time Post-Implantation | Tissue Response Phase | Impedance Change | Single-Unit Amplitude | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-24 hours | Acute inflammation | +50% to +100% | -20% to -40% | -15% to -30% |

| 1-4 weeks | Chronic inflammation | +150% to +300% | -50% to -80% | -40% to -70% |

| 4-12 weeks | Glial scar maturation | +200% to +500% | -70% to -90% | -60% to -85% |

| >12 weeks | Stable encapsulation | Stable at elevated levels | Stable at attenuated levels | Stable at reduced levels |

Long-Term Signal Stability and Recording Longevity

The chronic nature of the foreign body response fundamentally limits the functional longevity of neural recording interfaces. While flexible electrodes have demonstrated improved compatibility compared to rigid substrates, even advanced designs typically show progressive signal degradation over 4-8 month periods [17]. Studies investigating the long-term stability of single-unit recordings have found that only 15-30% of initially detectable units remain recordable after 6 months of implantation, with the remainder lost due to increasing interface impedance and neuronal displacement [15]. This signal decay follows an approximately exponential time course, with the most rapid decline occurring during the first 4-8 weeks post-implantation as the glial scar matures [17] [15]. The correlation between glial cell markers (GFAP, Iba1) expression levels and signal quality degradation provides compelling evidence for the causal relationship between the foreign body response and recording performance deterioration [15].

Comparative Analysis of Antifouling Strategies and Materials

Multiple material science and bioengineering approaches have been developed to mitigate biofouling at neural interfaces, each with distinct mechanisms of action and performance characteristics.

Material-Based Antifouling Strategies

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Neural Electrode Antifouling Strategies

| Strategy Category | Specific Approach | Mechanism of Action | Impact on Impedance | Recording Longevity | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flexible Substrates | Polyimide, parylene, silicone shafts | Reduced mechanical mismatch minimizes chronic inflammation | 30-50% lower initial increase | 2-4 month improvement | Reduced insertion stiffness requires shuttle assistance |

| Nanomaterial Coatings | Graphene, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) | High surface area maintains conductivity despite fouling | 40-60% reduction versus uncoated | 3-6 month improvement | Potential nanomaterial toxicity concerns |

| Conducting Polymers | PEDOT, PPy with bioactive doping | Decreased interfacial impedance combined with drug elution | 60-80% reduction versus metal | 4-8 month improvement | Limited long-term stability in physiological conditions |

| Surface Functionalization | PEG, peptide coatings, hydrogel layers | Physicochemical barrier against protein adsorption | 20-40% reduction | 1-3 month improvement | May increase initial electrode size |

| Drug Elution Systems | Dexamethasone, anti-inflammatory release | Local suppression of immune cell activation | 50-70% reduction | 4-12 month improvement | Finite drug reservoir requires reloading |

Mechanical Compatibility and Geometric Optimization

Recent advances in neural interface design have emphasized the critical importance of mechanical compatibility between the electrode and neural tissue. Traditional rigid electrodes (silicon, tungsten) with Young's moduli of 10²-10ⵠMPa create significant mechanical mismatch with brain tissue (1-10 kPa), exacerbating micromotion-induced inflammation [15]. Flexible electrodes using polyimide, parylene, or silicone substrates with Young's moduli of 0.5-5 GPa substantially reduce this mismatch, demonstrating 40-60% decreases in glial scarring compared to rigid counterparts in chronic implantations [17]. Ultra-flexible electrodes such as neurofilaments (<10 μm cross-section) and mesh electrodes have shown particularly promising results, with some studies reporting stable single-unit recordings for 8+ months in primate models [17]. Additionally, electrode geometry significantly influences the acute tissue damage during implantation, with smaller cross-sectional areas (<100 μm²) causing minimal vascular disruption and enabling more rapid tissue recovery [17].

Experimental Methodologies for Assessing Biofouling Impacts

Standardized experimental protocols are essential for quantitatively evaluating biofouling progression and the efficacy of antifouling strategies in neural interface research.

In Vivo Electrochemical and Electrophysiological Characterization

Comprehensive assessment of biofouling impacts requires multimodal experimental approaches that combine electrochemical measurements with histological validation. The following workflow outlines a standardized methodology for correlating electrical performance with biological response:

Key Methodological Considerations

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): Measurements should be performed across a broad frequency range (0.1 Hz to 100 kHz) to characterize both the charge transfer processes at the electrode surface (high frequency) and the tissue conductivity (low frequency) [15]. The phase angle at 1 kHz provides particularly valuable information about the capacitive versus resistive characteristics of the interface.

Signal Quality Metrics: Quantitative assessment should include signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), single-unit yield (detectable units per electrode), amplitude distribution, and spike sorting consistency across recording sessions [15]. These metrics should be tracked longitudinally to establish performance degradation timelines.

Histological Correlations: Following electrophysiological characterization, immunohistochemical analysis for GFAP (astrocytes), Iba1 (microglia), and NeuN (neurons) enables three-dimensional reconstruction of the tissue response [17] [15]. Critical parameters include glial scar thickness, neuronal density gradient, and direct measurement of neuron-to-electrode distances.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biofouling Studies

The systematic investigation of biofouling mechanisms and antifouling strategies requires specialized reagents and materials. The following table details essential components of the biofouling researcher's toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Neural Interface Biofouling Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrode Substrate Materials | Polyimide, parylene-C, silicone | Flexible electrode fabrication | Young's modulus, bending stiffness, biocompatibility |

| Conductive Coatings | PEDOT:PSS, graphene, CNT, iridium oxide | Interface impedance reduction | Charge storage capacity, charge transfer impedance |

| Immunohistochemistry Antibodies | Anti-GFAP, anti-Iba1, anti-NeuN | Cellular response characterization | Specificity, signal-to-background ratio, species compatibility |

| Anti-inflammatory Compounds | Dexamethasone, minocycline, IL-1ra | Local immunomodulation | Release kinetics, therapeutic concentration, duration of efficacy |

| Surface Modification Reagents | PEG-silane, peptide sequences (RGD, IKVAV) | Biofouling-resistant coatings | Grafting density, stability in physiological conditions |

| Electrochemical Characterization | Phosphate buffered saline, ferro/ferricyanide | In vitro impedance validation | Solution conductivity, redox couple reactivity |

Future Directions and Concluding Perspectives

The progressive deterioration of neural signal quality due to biofouling-induced interface impedance changes remains a fundamental challenge in chronic neural recording research. Future advances will likely emerge from integrated approaches that combine mechanically compliant substrate designs with active biofouling mitigation strategies such as controlled drug release and surface functionalization [17] [15]. Promising research directions include the development of biodegradable shuttle systems that eliminate chronic mechanical mismatch, conducting polymer composites with sustained anti-inflammatory release capabilities, and ultra-low modulus neural interfaces that approach the mechanical properties of brain tissue [17] [21]. Additionally, standardized experimental methodologies and rigorous longitudinal characterization will be essential for objectively comparing the performance of emerging antifouling technologies. As these innovations mature, they hold significant potential to extend the functional longevity of neural interfaces, ultimately enabling reliable decade-long neural recordings for both basic neuroscience research and clinical BCIs applications. The continued convergence of materials science, neural engineering, and immunology will be essential to develop next-generation neural interfaces that maintain signal fidelity by effectively mitigating the biofouling response.

Breakthrough Solutions: Innovative Materials, Electrode Designs, and Signal Processing Techniques

The pursuit of stable, long-term neural recordings represents a cornerstone of modern neuroscience and neuroengineering. The core challenge undermining this goal is the profound mechanical mismatch between conventional rigid neural probes and the soft, dynamic environment of brain tissue. This mismatch initiates a cascade of adverse biological reactions, ultimately leading to the degradation of recording fidelity over time. Traditional probes, typically fabricated from silicon or metals, possess a Young's modulus in the gigapascal (GPa) range, which is millions of times stiffer than brain tissue, with a modulus in the kilopascal (kPa) range [22] [23]. This disparity causes chronic inflammation, neuronal death, and the formation of an insulating glial scar around the implant, which increases electrode impedance and spatially separates the probe from its target neurons, thereby diminishing signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) [22] [17]. In response, ultra-flexible and biointegrated probes have emerged as a transformative solution. By achieving mechanical compatibility with the brain, these probes mitigate the foreign body response, enabling a more stable interface and superior long-term signal fidelity, which is critical for both foundational research and clinical applications such as brain-machine interfaces (BMIs) and therapeutic neuromodulation [24] [17].

Comparative Analysis of Neural Probe Technologies

The evolution of neural probes can be categorized into three distinct generations, each defined by its material composition, structural design, and strategy for interfacing with the brain. The following table provides a systematic comparison of their key characteristics and performance metrics.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Rigid, Flexible, and Ultra-Flexible/Biointegrated Neural Probes

| Feature | Conventional Rigid Probes | Flexible Polymer Probes | Ultra-Flexible/Biointegrated Probes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exemplar Technologies | Michigan probes, Utah arrays, Silicon probes [25] [22] | Polyimide-based probes, Open-sleeve electrodes [17] | Mechanically-adaptive (MA) probes, NeuroRoots, ROSE 3D probes, Ultraflexible electrode arrays [24] [26] [17] |

| Primary Materials | Silicon, Tungsten, Metals [25] [22] | Polyimide, Parylene C [17] | Polymer nanocomposites (e.g., PVAc with cellulose nanocrystals), ultra-thin metals [24] [23] |

| Young's Modulus | ~100 GPa (Silicon) [23] | ~1-10 GPa [17] | Dry: ~5 GPaImplanted/Wet: ~10 MPa [23] |

| Key Implantation Method | Direct insertion [25] | Rigid shuttle (e.g., tungsten wire, SU-8) [17] | Rigid shuttle, but with minimal cross-sectional area; ROSE 3D rolling approach [26] [17] |

| Chronic Signal Stability | Degrades over weeks due to glial scarring [22] [23] | Improved over rigid probes; stable recordings for months reported [17] | High stability; demonstrated stable recordings after extended stimulation periods [24] [23] |

| Typical Stimulation Current | ~100-500 µA (for behavioral control) [24] | Information Not Available | ~5 µA (for precise behavioral control in mice) [24] |

| Tissue Response (Gliosis) | Significant glial scar formation [22] [23] | Reduced glial scarring compared to rigid probes [17] | Minimized glial scarring; improved neuronal density near the implant [23] |

| Key Advantage | Reliable surgical insertion | Better mechanical match than rigid probes | Ultimate mechanical compatibility, low-threshold stimulation |

| Key Challenge | Chronic inflammation, signal loss | Requires complex implantation strategies | Fabrication, handling, and implantation complexity |

The experimental data underscores the performance benefits of ultra-flexible probes. A direct comparison of implantation mechanics reveals that flexible probes significantly reduce tissue strain. Furthermore, the functional superiority of ultra-flexible probes is demonstrated by their dramatically lower stimulation thresholds and enhanced recording stability, as shown in the table below.

Table 2: Quantitative Experimental Data from Ultra-Flexible Probe Studies

| Performance Metric | Experimental Finding | Probe Type | Biological Model | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stimulation Current Threshold | ~5 µA to induce turning behavior in mice [24] | Ultraflexible electrode array | Mouse | 1-2 orders of magnitude lower than conventional rigid electrodes, enabling precise neuromodulation with minimal energy [24] |

| Neural Recording Stability | Stable spike recordings maintained after extended electrical stimulation [24] | Ultraflexible electrode array | Mouse | Probes maintain stable electrical contact, indicating health of both neurons and electrodes [24] |

| Single-Unit Recording Yield | Improved active electrode yield and signal amplitude over 12 weeks [23] | MARE (Mechanically-adaptive, resveratrol-eluting) probe | Rat | Combination of flexibility and anti-inflammatory drug delivery supports chronic recording stability [23] |

| Post-Implantation Elastic Modulus | Softens from ~5 GPa (dry) to ~10 MPa (implanted) [23] | MARE probe | In vitro / ex vivo | Reduces mechanical mismatch with brain (~10 kPa) by a factor of 10âµ compared to silicon [23] |

| Gene Expression & Tissue Response | Healing tissue response and reduced expression of pro-inflammatory markers [23] | MARE probe | Rat | Probe integration attenuates key drivers of the neuroinflammatory cascade, favoring a healing environment [23] |

Experimental Protocols for Validating Probe Performance

Protocol 1: In Vivo Electrophysiology and Behavioral Modulation

This protocol is designed to quantify the efficacy of ultra-flexible probes in recording neural activity and evoking specific behaviors through low-threshold electrical stimulation [24].

- Objective: To validate the functionality of ultraflexible electrode arrays in simultaneously recording single-neuron spikes and modulating complex motor behavior with high precision and low current.

- Probe Implantation: Ultraflexible electrode arrays are implanted into the target brain region, such as the secondary motor cortex (M2) of mice, using a rigid shuttle (e.g., tungsten wire) for guidance. The shuttle is retracted after implantation, leaving the flexible probe in place [17].

- Neural Recording & Behavior Correlation: In freely moving mice, neural signals (spike firings) are recorded continuously alongside video tracking of animal behavior. The firing rates of individual neurons are correlated with motion parameters (e.g., velocity) to confirm proper probe placement and functional recording [24].

- Low-Current Electrical Stimulation: Biphasic, charge-balanced current pulses are delivered through individual microelectrodes on the array. A typical waveform consists of a 200 µs cathodic phase, a 100 µs interphase delay, and a 400 µs anodic phase at half the amplitude, delivered at 100 Hz. The current is systematically varied to find the minimum threshold (e.g., ~5 µA) required to reliably evoke a contralateral turning behavior [24].

- Data Analysis: Angular and linear displacement of the animal are quantified from video tracking. The specificity of behavior induction is assessed by stimulating different electrodes within the array to map functional brain regions [24].

Protocol 2: Finite Element Analysis of Implantation Mechanics

This computational protocol assesses the mechanical interaction between the probe and brain tissue during and after insertion, providing a basis for optimizing probe design [25].

- Objective: To simulate the implantation process and quantify induced stresses and strains in brain tissue, predicting the potential for acute and chronic tissue damage.

- Model Establishment: A finite element (FE) model is developed using a Coupled Eulerian-Lagrangian (CEL) method in software like ABAQUS. The probe is modeled as a Lagrangian solid with precise geometric dimensions, while the brain tissue is represented as an Eulerian domain to accommodate large deformations [25].

- Material Properties: Brain tissue is modeled as a hyperelastic, viscoelastic material to capture its nonlinear, strain-rate-dependent mechanical behavior. Material parameters are derived from experimental tests on ex vivo porcine brain tissue, which is biomechanically comparable to human tissue [25].

- Simulation Parameters: The model simulates the insertion of single-shank and multi-shank arrays at controlled speeds (e.g., 1 mm/s) to a specified depth (e.g., 1 mm). Parameters such as implantation force, stress distribution, and strain fields in the tissue are calculated [25].

- Experimental Validation: The simulation results, particularly the force-displacement profiles, are validated against physical implantation experiments using the same probe designs and fresh porcine brain tissue [25].

The workflow and key interactions in the neural tissue response to an implanted probe are illustrated below.

(caption: Signaling Pathways in the Brain Tissue Response to Neural Probes) This diagram contrasts the detrimental cascade triggered by mechanically mismatched rigid probes (red nodes) with the beneficial outcomes promoted by ultra-flexible and biointegrated strategies (green nodes). Dashed green lines represent inhibitory effects, showing how flexibility and drug elution disrupt the pathway to signal failure.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful development and deployment of ultra-flexible neural probes rely on a suite of specialized materials and reagents. The following table details key components of the research toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Ultra-Flexible Neural Probes

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Polyvinyl Acetate (PVAc) & Cellulose Nanocrystals | Forms the mechanically-adaptive polymer nanocomposite substrate; rigid for insertion, softens upon implantation [23]. | Core substrate material for MARE probes [23]. |

| Parylene C | A biocompatible polymer used as a thin-film insulation layer to encapsulate metal traces and control drug release kinetics [23]. | Insulation and diffusion-control layer in MARE probes [23]. |

| Resveratrol | A natural polyphenol antioxidant incorporated into the probe substrate for local elution to mitigate oxidative stress and neuroinflammation [23]. | Active drug component in MARE probes to scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS) [23]. |

| Gold (Au) & Titanium (Ti) | Thin-film metals used for conductive traces (Au) and as an adhesion layer (Ti) between the substrate and metal [25] [23]. | Microelectrodes and interconnects in flexible probe fabrication [24] [23]. |

| Titanium Nitride (TiN) | A conductive and biocompatible material coating electrode sites to lower interfacial impedance and increase charge injection capacity [25]. | Functional modification layer on electrode contact points [25]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | A biodegradable polymer used as a temporary coating to secure a rigid shuttle to a flexible probe, dissolving after implantation to release the shuttle [17]. | "Glue" in tungsten wire-guided implantation of rod-like flexible electrodes [17]. |

| Selfotel | Selfotel, CAS:110347-85-8, MF:C7H14NO5P, MW:223.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Mogroside IIA1 | Mogroside IIA1, CAS:88901-44-4, MF:C42H72O14, MW:801.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The evidence unequivocally demonstrates that ultra-flexible and biointegrated neural probes represent a paradigm shift in neural interface technology. By fundamentally addressing the problem of mechanical mismatch, these probes successfully attenuate the chronic neuroinflammatory response, which is the primary obstacle to long-term signal fidelity. The resulting stability in single-unit recording and the ability to achieve precise neuromodulation with exceptionally low currents underscore a future where high-performance brain-computer interfaces can operate reliably for decades. Future developments will likely focus on integrating multi-modal functionalities, such as electrical recording, stimulation, and drug delivery, into ever-smaller and more compliant form factors. Furthermore, the creation of sophisticated 3D interfaces, such as those enabled by the ROSE technique, will allow for unprecedented mapping and modulation of neural circuits across different depths [26]. As materials science and implantation strategies continue to advance, the distinction between man-made devices and neural tissue will continue to blur, finally providing neuroscientists and clinicians with the robust and stable tools needed to unlock the brain's deepest secrets and treat its most debilitating diseases.

Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) enable direct communication between the brain and computers, offering transformative potential for treating neurological disorders and restoring neural functions. However, their long-term functionality remains severely limited by signal degradation caused by acute insertion trauma, chronic foreign body reaction (FBR), and biofouling at the device-tissue interface [10] [27]. When implanted, conventional neural devices trigger a cascade of biological responses, including acute inflammation from surgical trauma that progresses to chronic FBR, often leading to glial scarring and eventual encapsulation of the device [27]. This insulation effect increases the distance between neurons and electrode sites, causing rapid signal attenuation and a sharp rise in impedance, ultimately compromising signal quality and long-term functionality [17].

Surface engineering has emerged as a critical strategy to mitigate these challenges. While various antifouling surface modifications have demonstrated success in reducing immune responses, their extreme repellency often inhibits direct interaction between the device and neurons, diminishing neural recording sensitivity and selectivity [27]. Similarly, approaches featuring biomolecule conjugation to promote neural interaction often suffer from rapid biodegradation in vivo [27]. To address these competing challenges, a new class of bioadaptive coatings has been developed, with the Targeting-specific interaction and Blocking nonspecific adhesion (TAB) coating representing a particularly advanced solution that achieves synergistic integration of mechanical compliance and biochemical stability for transformative long-term neural recording capabilities.

Technology Comparison: TAB Coating Versus Alternative Approaches

TAB Coating: Mechanism and Composition

The TAB coating employs a sophisticated dual-functional design that combines brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) conjugation with a lubricant-infused surface [10] [27]. This architecture features alternately immobilized perfluorosilane (PFS) and aminosilane layers. The PFS component imparts low surface energy for holding a slippery lubricant layer, while the aminosilane serves as an anchor for BDNF [27]. The immobilized BDNF facilitates selective interaction with neurons and astrocytes by binding to tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB) receptors, while the lubricant layer repels nonspecific adhesions, reducing the attachment of blood and plasma proteins to less than 3% [27].

This design enables multiple protective functions: the lubricant layer minimizes friction during insertion, reducing acute insertion trauma, while simultaneously preventing immune cell adhesion and migration to the BDNF, which prevents immune cell activation and degradation of the biomolecules [27]. Meanwhile, the BDNF component promotes beneficial interactions with neural cells, supporting survival and growth of neurons and astrocytes, particularly promoting the neuroprotective A2 astrocyte subtype [27].

Comparative Analysis of Neural Interface Coatings

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Neural Interface Coating Technologies

| Coating Technology | Mechanism of Action | Signal Stability Duration | Cell Adhesion Profile | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAB Coating | BDNF conjugation + lubricant-infused surface | >12 months [10] [27] | Selective (↑ neurons/astrocytes, ↓ immune cells) [27] | Complex fabrication process |

| Hydrophilic Coatings | Surface hydration layer prevents protein adsorption | Months [28] | Non-specific reduction [27] | Inhibits neural interaction, limited long-term stability |

| Diamond-Like Carbon (DLC) | Physical barrier with biocompatibility | Limited long-term data [29] | Non-specific reduction [29] | Requires precise tip exposure, no bioactive component |

| Biomolecule Conjugation | Peptides/proteins promote specific interactions | Limited by biodegradation [27] | Selective (↑ neural cells) | Subject to enzymatic degradation, doesn't address friction |

| Antifouling Polymers | Steric hindrance prevents protein adhesion | Months [30] | Broad-spectrum reduction [27] | Also repels beneficial neural interactions |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Coating Technologies

| Performance Metric | TAB Coating | Hydrophilic Coatings | DLC-UME | Uncoated Controls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Adhesion Reduction | >97% [27] | ~90% [28] | Not specified | Baseline |

| Neuronal Cell Coverage | ~65% after 1 week [27] | <10% [27] | Not specified | ~20% declining |

| Acute Insertion Trauma | Significantly reduced [27] | Moderate | Not specified | High |

| Chronic FBR Suppression | High [10] | Moderate [17] | Not specified | Minimal |

| Single-Unit Recording Stability | >12 months [10] | 3-6 months [17] | Improved short-term [29] | Weeks to months |

Experimental Analysis: Methodologies and Data Interpretation

TAB Coating Fabrication and Evaluation Protocols

The experimental validation of TAB coatings followed rigorous methodologies across multiple studies. The coating was applied to flexible multifunctional neural fibers fabricated through a thermal drawing process (TDP), which allows miniaturization and integration of functional modalities into fibers by preserving the cross-sectional structure [27]. The resulting microscale polymeric fiber exhibited exceptional flexibility with a flexural rigidity of 1.49 × 10â»â· N/m² [27].

The TAB coating application process involved:

- Surface Functionalization: Sequential immobilization of perfluorosilane (PFS) and aminosilane layers onto the fiber surface [27].

- BDNF Conjugation: Covalent attachment of brain-derived neurotrophic factor to the aminosilane anchors [27].

- Lubricant Infusion: Application of a thin lubricant layer onto the PFS component to create a slippery surface [27].

Performance characterization included:

- Antifouling Assessment: Quantification of blood and plasma protein adhesion using fluorescence tagging [27].

- Cell Selectivity Evaluation: Co-cultures of neurons, astrocytes, and immune cells to measure selective adhesion [27].

- Electrochemical Analysis: Electrode impedance and charge transfer efficiency measurements [27].

- In Vivo Validation: Long-term implantation in mouse models with continuous neural signal monitoring [27].

Ultramicroelectrode Tip Exposure Control Methodology

Complementary research on ultramicroelectrodes (UMEs) provides additional insights into precision surface engineering. A recent study developed a novel technique using a cold atmospheric microplasma jet to control the exposure of ultramicroelectrode tips protected with diamond-like carbon (DLC) coatings [29]. The methodology included:

- DLC Deposition: Conformal coating of UMEs with protective diamond-like carbon [29].

- Selective Removal: Precision exposure of electrode tips using microplasma jet treatment with submicron accuracy [29].

- Biocompatibility Validation: Cell culture with neuronal cells to confirm non-adverse effects on growth [29].

- Electrochemical Testing: Impedance spectroscopy and intracellular pH detection to verify performance [29].

This approach demonstrated that controlled tip exposure significantly improves signal-to-noise ratio and sensitivity while maintaining biocompatibility [29].

Signaling Pathways in TAB-Coated Neural Interfaces

The TAB coating's exceptional performance stems from its orchestrated interaction with specific biological pathways. The diagram below illustrates the key signaling mechanisms involved in the tissue response to TAB-coated neural interfaces.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Bioadaptive Coating Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) | Promotes neural cell adhesion and survival via TrkB receptors [27] | TAB coating bioactive component |

| Perfluorosilane (PFS) | Creates low-energy surface for lubricant retention [27] | TAB coating antifouling component |

| Aminosilane | Provides anchoring sites for biomolecule conjugation [27] | TAB coating immobilization |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Temporary stiffening agent for implantation [17] | Flexible electrode delivery |

| Diamond-Like Carbon (DLC) | Protective biocompatible coating with mechanical strength [29] | Ultramicroelectrode insulation |

| Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):Poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) | Conductive polymer for electrode interface [31] | Neural recording and stimulation |

| Hydroxyapatite | Bioceramic promoting bone integration [30] | Orthopedic and dental implants |

| Phosphorylcholine | Mimics cell membranes for blood compatibility [30] | Cardiovascular devices |

| Gold Nanowires | Conductive nanomaterial for flexible electronics [31] | Stretchable neural interfaces |

| Silk Fibroin | Biocompatible, programmable substrate [31] | Flexible bioelectronic implants |

| SSTR5 antagonist 2 | SSTR5 antagonist 2, CAS:1254730-81-8, MF:C32H35FN2O5, MW:546.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Isorhoifolin | Isorhoifolin, CAS:36790-49-5, MF:C27H30O14, MW:578.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Comparative Data Interpretation: Quantitative Advantages of TAB Coatings

Long-Term Performance Metrics

The exceptional long-term performance of TAB coatings is demonstrated through quantitative comparison with alternative approaches. In vivo studies showed that TAB-coated fibers maintained high-quality single-unit neural signals for more than 12 months post-implantation, significantly outperforming uncoated controls which typically lost signal recording capability within a few months [27]. This represents one of the longest stable recording durations reported in the literature for implantable neural interfaces.

Cell culture studies further quantified the selective interfacial properties of TAB coatings, demonstrating approximately 25% neural cell coverage after 1 day, proliferating to 65% after 1 week [27]. This contrasts sharply with conventional antifouling coatings which typically show less than 10% neural cell coverage due to their non-specific repellency [27]. The TAB coating's ability to simultaneously promote desired neural interactions while minimizing unwanted immune cell adhesion represents a fundamental advancement in surface engineering for neural interfaces.

Mechanical and Biochemical Synergy

The experimental data reveals that the TAB coating's success derives from its synergistic combination of mechanical and biochemical mitigation strategies. The lubricant component reduces friction during implantation, minimizing acute tissue trauma, while simultaneously creating a barrier that protects conjugated BDNF from proteolytic degradation and immune cell recognition [27]. This dual functionality addresses both the initial insertion damage and chronic degradation pathways that conventionally limit coating lifespan.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy demonstrated that TAB-coated electrodes maintained stable electrical properties throughout the 12-month implantation period, with significantly lower increases in interface impedance compared to uncoated controls [27]. This indicates that the coating successfully mitigated the glial scarring and encapsulation that typically degrades electrode performance over time.

TAB coatings represent a significant paradigm shift in neural interface design, moving beyond singular-function coatings toward multifunctional surface systems that actively manage the biological interface. The experimental data demonstrates that the integration of mechanical compliance, selective biochemical signaling, and broad-spectrum antifouling properties enables unprecedented long-term signal stability exceeding 12 months [10] [27].